Jan 3-6, 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter One Phonetic Change

CHAPTERONE PHONETICCHANGE The investigation of the nature and the types of changes that affect the sounds of a language is the most highly developed area of the study of language change. The term sound change is used to refer, in the broadest sense, to alterations in the phonetic shape of segments and suprasegmental features that result from the operation of phonological process es. The pho- netic makeup of given morphemes or words or sets of morphemes or words also may undergo change as a by-product of alterations in the grammatical patterns of a language. Sound change is used generally to refer only to those phonetic changes that affect all occurrences of a given sound or class of sounds (like the class of voiceless stops) under specifiable phonetic conditions . It is important to distinguish between the use of the term sound change as it refers tophonetic process es in a historical context , on the one hand, and as it refers to phonetic corre- spondences on the other. By phonetic process es we refer to the replacement of a sound or a sequenceof sounds presenting some articulatory difficulty by another sound or sequence lacking that difficulty . A phonetic correspondence can be said to exist between a sound at one point in the history of a language and the sound that is its direct descendent at any subsequent point in the history of that language. A phonetic correspondence often reflects the results of several phonetic process es that have affected a segment serially . Although phonetic process es are synchronic phenomena, they often have diachronic consequences. -

Glossary of Key Terms

Glossary of Key Terms accent: a pronunciation variety used by a specific group of people. allophone: different phonetic realizations of a phoneme. allophonic variation: variations in how a phoneme is pronounced which do not create a meaning difference in words. alveolar: a sound produced near or on the alveolar ridge. alveolar ridge: the small bony ridge behind the upper front teeth. approximants: obstruct the air flow so little that they could almost be classed as vowels if they were in a different context (e.g. /w/ or /j/). articulatory organs – (or articulators): are the different parts of the vocal tract that can change the shape of the air flow. articulatory settings or ‘voice quality’: refers to the characteristic or long-term positioning of articulators by individual or groups of speakers of a particular language. aspirated: phonemes involve an auditory plosion (‘puff of air’) where the air can be heard passing through the glottis after the release phase. assimilation: a process where one sound is influenced by the characteristics of an adjacent sound. back vowels: vowels where the back part of the tongue is raised (like ‘two’ and ‘tar’) bilabial: a sound that involves contact between the two lips. breathy voice: voice quality where whisper is combined with voicing. cardinal vowels: a set of phonetic vowels used as reference points which do not relate to any specific language. central vowels: vowels where the central part of the tongue is raised (like ‘fur’ and ‘sun’) centring diphthongs: glide towards /ə/. citation form: the way we say a word on its own. close vowel: where the tongue is raised as close as possible to the roof of the mouth. -

Preceding Phonological Context Effects on Palatalization in Brazilian Portuguese/English Interphonology

Preceding Phonological Context... 63 PRECEDING PHONOLOGICAL CONTEXT EFFECTS ON PALATALIZATION IN BRAZILIAN PORTUGUESE/ENGLISH INTERPHONOLOGY Melissa Bettoni-Techio Rosana Denise Koerich Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Abstract This article reports a study investigating the effects of the preceding context on palatalization of word-final alveolar stops by Brazilian learners of English. Thirty learners with 150 hours of formal instruction in English read a sentence list in the FL including 240 tokens of final alveolar stops in different preceding and following context combinations. The hypothesis investigated was that high vowels and rising diphthongs in the preceding context would cause more palatalization than mid and low vowels due to carryover effects from vowels to the target sound. The hypothesis was supported. A hierarchy of difficulty concerning preceding phonological contexts was established from the results. The combination of preceding and following phonological contexts was also investigated. Keywordsds: palatalization, interphonology, phonological context. Ilha do Desterro Florianópolis nº 55 p. 063-081 jul./dez. 2008 64 Melissa Bettoni-Techio & Rosana Denise Koerich 1. Introduction In general, phonologists and phoneticians agree that a universal principle of sound systems is that sound units are influenced by their adjacent elements, assuming different phonetic values, according to processes such as assimilation, elision, liaison, and epenthesis (Jackson, 1980; Laver, 1994; Wolfram & Johnson, 1982). Bearing in mind the claim that interlanguages undergo the same phonological processes of natural languages (Eckman, 1991), the above statement can be considered to be true for interlanguages as well. In Brazil, research has investigated the change of features of word- final consonants in Brazilian Portuguese (BP)/English interphonology concerning phonological context (e.g., Kluge, 2004). -

Between Natural and Unnatural Phonology: the Case of Cluster-Splitting Epenthesis Juliette Blevins the Graduate Center, CUNY

Chapter 1 Between natural and unnatural phonology: The case of cluster-splitting epenthesis Juliette Blevins The Graduate Center, CUNY A widely recognized feature of loan-word phonology is the resolution of clusters by vowel epenthesis. When a language lacking word-initial clusters borrows words from a language with initial #TRV sequences, T an oral stop and R a liquid, it is common to find vowel epenthesis, most typically vowel-copy, as in, for example: Basque <gurutze> ‘cross’ from Latin <cruce(m)>; Q’eqchi’ <kurus> ‘cross’ from Spanish <cruz> ‘cross’, or Fijian <kolosi> ‘cross’ from English <cross>. The phonological rule or sound change responsible for this pat- tern is sometimes called “cluster-splitting epenthesis”: #TRVi > #TV(i)RVi. The most widely accepted explanation for this pattern is that vowel epenthesis between the oral stop andthe following sonorant is due to the vowel-like nature of the TR transition, since #TRVi is per- ceptually similar to #TV(i)RVi. A fact not often appreciated, however, is that cluster-splitting epenthesis is extremely rare as a language-internal development. The central premise of this chapter is that #TRVi in a non-native language is heard or perceived as #TV(i)RVi when phonotactics of the native language demand TV transitions. Without this cognitive compo- nent, cluster-splitting epenthesis is rare and, as argued here, decidedly unnatural. 1 Introduction Diachronic explanations have been offered for both natural and unnatural sound pat- terns in human spoken languages. Building on the Neogrammarian tradition, as well as the experimental research program of Ohala (e.g. 1971; 1974; 1993), it is argued that natural sound patterns, like final obstruent devoicing, nasal place assimilation, vowel harmony, consonant lenition, and many others, arise from regular sound changes with clear phonetic bases (Blevins 2004, 2006, 2008, 2015; Anderson 2016). -

The Tune Drives the Text - Competing Information Channels of Speech Shape Phonological Systems

The tune drives the text - Competing information channels of speech shape phonological systems Cite as: Roettger, Timo B. & Grice, Martine (2019). The tune drives the text - Competing information channels of speech shape phonological systems. Language Dynamics and Change, 9(2), 265–298. DOI: 10.1163/22105832-00902006 Abstract In recent years there has been increasing recognition of the vital role of intonation in speech communication. While contemporary models represent intonation – the tune – and the text that bears it on separate autonomous tiers, this paper distils previously unconnected findings across diverse languages that point to important interactions between these two tiers. These interactions often involve vowels, which, given their rich harmonic structure, lend themselves particularly well to the transmission of pitch. Existing vowels can be lengthened, new vowels can be inserted and loss of their voicing can be blocked. The negotiation between tune and text ensures that pragmatic information is accurately transmitted and possibly plays a role in the typology of phonological systems. Keywords: Intonation, epenthesis, devoicing, lengthening, phonological typology Acknowledgment Funding from the German Research Foundation (SFB 1252 Prominence in Language) is gratefully acknowledged. We would like to thank Aviad Albert, James German, Márton Sóskuthy, and Andy Wedel for their comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript. We would like to thank the Departments of Linguistics at the University of Cologne, the Goethe University in Frankfurt, Northwestern University in Evanston, the Institute of Phonetics and Speech Processing at the University of Munich, and the audience of XLanS in Lyon for their valuable input on this project. Finally, we would like to express our gratitude to three anonymous reviewers and the editor Jeff Good for their comments during the review process. -

Historical Linguistics and the Comparative Study of African Languages

Historical Linguistics and the Comparative Study of African Languages UNCORRECTED PROOFS © JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY 1st proofs UNCORRECTED PROOFS © JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY 1st proofs Historical Linguistics and the Comparative Study of African Languages Gerrit J. Dimmendaal University of Cologne John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam / Philadelphia UNCORRECTED PROOFS © JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY 1st proofs TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American 8 National Standard for Information Sciences — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dimmendaal, Gerrit Jan. Historical linguistics and the comparative study of African languages / Gerrit J. Dimmendaal. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. African languages--Grammar, Comparative. 2. Historical linguistics. I. Title. PL8008.D56 2011 496--dc22 2011002759 isbn 978 90 272 1178 1 (Hb; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 1179 8 (Pb; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 8722 9 (Eb) © 2011 – John Benjamins B.V. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. John Benjamins Publishing Company • P.O. Box 36224 • 1020 me Amsterdam • The Netherlands John Benjamins North America • P.O. Box 27519 • Philadelphia PA 19118-0519 • USA UNCORRECTED PROOFS © JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY 1st proofs Table of contents Preface ix Figures xiii Maps xv Tables -

Word-Final Vowel Epenthesis Ng E-Ching · [email protected] · National University of Singapore · 9 January 2017

A sound change with L2 origins: Word-final vowel epenthesis Ng E-Ching · [email protected] · National University of Singapore · 9 January 2017 1. Overview (1) The controversy: simplicity a. A creole is a (i) massively restructured (ii) L2 that has become an L1. b. Are creoles simple languages? i. Bioprogram: child L1 acquisition simple grammars (Bickerton 1984) Discredited: bilingual creolisation in Hawaii (Roberts 2000; Siegel 2006) ii. Creole prototype: adult L2 acquisition simple grammars (McWhorter 1998) Discredited: average phoneme inventories, syllable templates (Klein 2011) (2) My hypothesis: transmission bias a. Creoles are simple different. b. The differences are synchronic diachronic. c. Missing sound changes can be traced to child L1 learners’ cognitive biases adult L2 learners’ phonetic biases. (3) Today’s missing sound change: paragoge Word-final consonant repairs Language contact L1 transmission a. Vowel big > bigi rare b. Consonant big > bik > biʔ > bi Some terms: epenthesis: insertion paragoge: word-final epenthesis 2. Data (4) Examples of paragoge (refs. in Ng 2015: 115ff; Plag 2009: 131; Hammarberg 1994) a. Pidgins and creoles English walk > Jamaican Maroon Spirit Language waka copy vowel English school > Solomon Islands Pidgin sukulu copy vowel Portuguese doutor > São Tome dotolo ‘doctor’ copy vowel Dutch pompoen > Berbice Dutch Creole pampuna ‘pumpkin’ b. Loanword adaptation English ice > Japanese [aisu] ‘ice cream’ reduced vowel French avec ‘with’ > Korean [apεk’ɨ] ‘dating couple’ reduced vowel Arabic nūr > Swahili [nuru] ‘light’ copy vowel Malay burung > Malagasy [vorona] ‘bird’ c. L2 acquisition Mandarin English red [redə] placeless vowel Cantonese English blanket [blæŋkətə ̥̆ ] placeless vowel German Swedish familj [fəmiljə] ‘family’ placeless vowel Brazilian Portuguese English dog [dogi] 2 (5) Language contact: Paragoge is everywhere (refs. -

An Analysis of Phonemic and Graphemic Changes of English Loanwords in Bahasa Indonesia Appearing in Magazine Entitled “Chip”

ISSN: 2549-4287 Vol.1, No.1, February 2017 AN ANALYSIS OF PHONEMIC AND GRAPHEMIC CHANGES OF ENGLISH LOANWORDS IN BAHASA INDONESIA APPEARING IN MAGAZINE ENTITLED “CHIP” Juliawan, M.D. English Education Department, Ganesha University of Education e-mail: [email protected] Abstract This research aimed to describe the phonemic and graphemic changes of English loanwords in Bahasa Indonesia appearing in magazine entitled ‘CHIP’. The subjects of this research were the writers/editors of each articles of CHIP magazine. The objects of this research were English loanwords in Indonesian appearing in CHIP magazine ranging from 2013 to 2015 edition plus with the special edition of CHIP. The data were collected by reading and giving a mark to each borrowing words found or spotted in technology magazine (CHIP) through the process of reading. This study was a descriptive qualitative research which applying interactive data anaylisis model in analyzing the collected data. The results of this study show there are 12 processes of phonemic changes specifically for consonants. There are 8 processes of phoneme shift, 2 processes of phoneme split, and 2 processes of apocope. There are 10 phonemic changes of vowel: 1 process of phoneme split, 2 processes of phoneme shift, 2 processes of phoneme merger and 5 processes of paragoge. There are two types of graphemic changes found, namely pure phonological adaptation and syllabic adaptation. In the syllabic adaptation process, there are four processes of graphemic change, namely (1) double consonants become single consonant, (2) double vowels become single vowel, (3) monosyllable become disyllable, and (4) consonant inhibitory at the end of consonant clusters is disappear. -

Chapter 3 BASIC THEORETICAL ELEMENTS and THEIR

Chapter 3: Basic elements 136 The perceptual salience of a segment – or its degree of confusability with Chapter 3 zero – is a function of the quantity and quality of the auditory cues that signal its BASIC THEORETICAL ELEMENTS presence in the speech stream. The best cues to consonants, apart from those present in the consonants themselves, are found in neighboring vowels, especially in the CV AND THEIR PERCEPTUAL MOTIVATIONS transition. It is the desirability for consonants to benefit from these vocalic cues that generalization 1 expresses. But cues may also come from other sources, and the perceptibility of a consonant without the support of an adjacent or following vowel The preceding chapter identified a number of empirical generalizations, which depends on these non-(pre)vocalic cues. Generalizations 2-6 identify factors that condition the application of consonant deletion, vowel epenthesis, and vowel negatively affect these cues, and consequently enhance the desirability of an adjacent deletion. These output generalizations are summarized below. vowel in order to meet the principle in (1). Generalization 1: Consonants want to be adjacent to a vowel, and preferably I assume that consonant deletion and vowel epenthesis are motivated by the followed by a vowel. principle of perceptual salience; they apply when a consonant lacks perceptual salience and becomes more easily confusable with nothing, that is when the cues that Generalization 2: Stops want to be adjacent to a vowel, and preferably followed permit a listener to detect its presence are diminished. Deletion removes such by a vowel. deficient segments, epenthesis provides them with the needed additional salience. -

Autosegmental Representation of Epenthesis in the Spoken French of Ijebu Undergraduate French Learners in Selected Universities in South-West of Nigeria

123 AFRREV, VOL. 9(4), S/NO 39, SEPTEMBER, 2015 An International Multidisciplinary Journal, Ethiopia Vol. 9(4), Serial No. 39, September, 2015:123-138 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070-0083 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.v9i4.10 Autosegmental Representation of Epenthesis in the Spoken French of Ijebu Undergraduate French Learners in Selected Universities in South-West of Nigeria Iyiola, Amos Damilare Department of European Studies University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] Phone: +2348053144710 Abstract Insertion of vowels and consonants is a phonological process in language. Existing studies have examined vowel insertion in several languages and dialects with little attention paid to the spoken French of Ijebu Undergraduates. Therefore, this paper examined vowel insertion in the spoken French of 50 Ijebu Undergraduate French Learners (IUFLs) in Selected Universities in South West of Nigeria. The data collection for this study was through tape-recording of participants’ production of 30 sentences containing both French vowel and consonant sounds while Goldsmith’s Autosegmental phonology blended with distinctive feature theory was used to analyse instances of insertion in the data collected such as i-epenthetic and u-epenthetic at the initial, medial and final positions in the spoken French of IUFLs. Key words: IUFLs, Epenthensis, Ijebu dialect, Autosegmental phonology Copyright © IAARR, 2015: www.afrrevjo.net Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info 124 AFRREV, VOL. 9(4), S/NO 39, SEPTEMBER, 2015 Introduction Insertion is a phonological process whereby an extraneous element not present originally is introduced into the utterance usually to break up unwanted sequences. -

The Phonological Changes from Gelgel Dialect to Tampekan Dialect: a Descriptive Qualitative Study

THE PHONOLOGICAL CHANGES FROM GELGEL DIALECT TO TAMPEKAN DIALECT: A DESCRIPTIVE QUALITATIVE STUDY K. P. Ariantini, I. W. Suarnajaya, I. G. Budasi Jurusan Pendidikan Bahasa Inggris, Fakultas Bahasa dan Seni Universitas Pendidikan Ganesha Jalan Jend. A Yani 67 Singaraja 8116, Telp. 0362-21541, Fax. 0362-27561 Email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRAK Penelitian ini bertujuan untuk mendeskripsikan perubahan bahasa dari dialek Gelgel ke dialek Tampekan. Penelitian ini merupakan penelitian deskripsi kualitatif. Peneliatian ini mengambil tempat di desa Gelgel, kecamatan Klungkung, kabupaten Klungkung dan di desa Tampekan, kecamatan Banjar, kabupaten Buleleng. Ada tiga informan yang dipilih ditiap desa. Satu orang sebagai informan yang utama, dua orang lainnya sebagai informan yang membantu. Data dianalisis berdasarkan teori tipe perubahan bahasa yang disarankan oleh Crowley (1992), Keraf (1996), and Fruehwald (2013). Data diperoleh berdasarkan daftar kata Swadesh dan daftar kata Nothofer. Hasil dari data analisis menunjukan bahwa ada 8 kata yang mengalami aphaeresis (menghilangnya fonem di depan kata), 10 kata yang mengalami syncope (menghilangnya fonem di tengah kata), 2 kata yang mengalami apocope (menghilangnya fonem diakhir kata), 7 kata yang mengalami haplology (menghilangnya suku kata dalam sebuah kata), 7 kata yang mengalami epenthesis (penambahan fonem di depan kata), 2 kata yang mengalami prosthesis (penambahan ditengah kata), 4 kata yang mengalami paragoge (penambahan fonem di akhir kata), 6 kata yang mengalami assimilation (sebuah fonem yang mengubah fonem lainnya dan terdengan mirip), and 7 kata yang mengalami dissimilation (perubahan fonem yang tidak mirip dari sebelumnya). Kata kunci: fonologi, perubahan bunyi, dialek. ABSTRACT This study aimed at describing the phonological changes from Gelgel dialect to Tampekan dialect. -

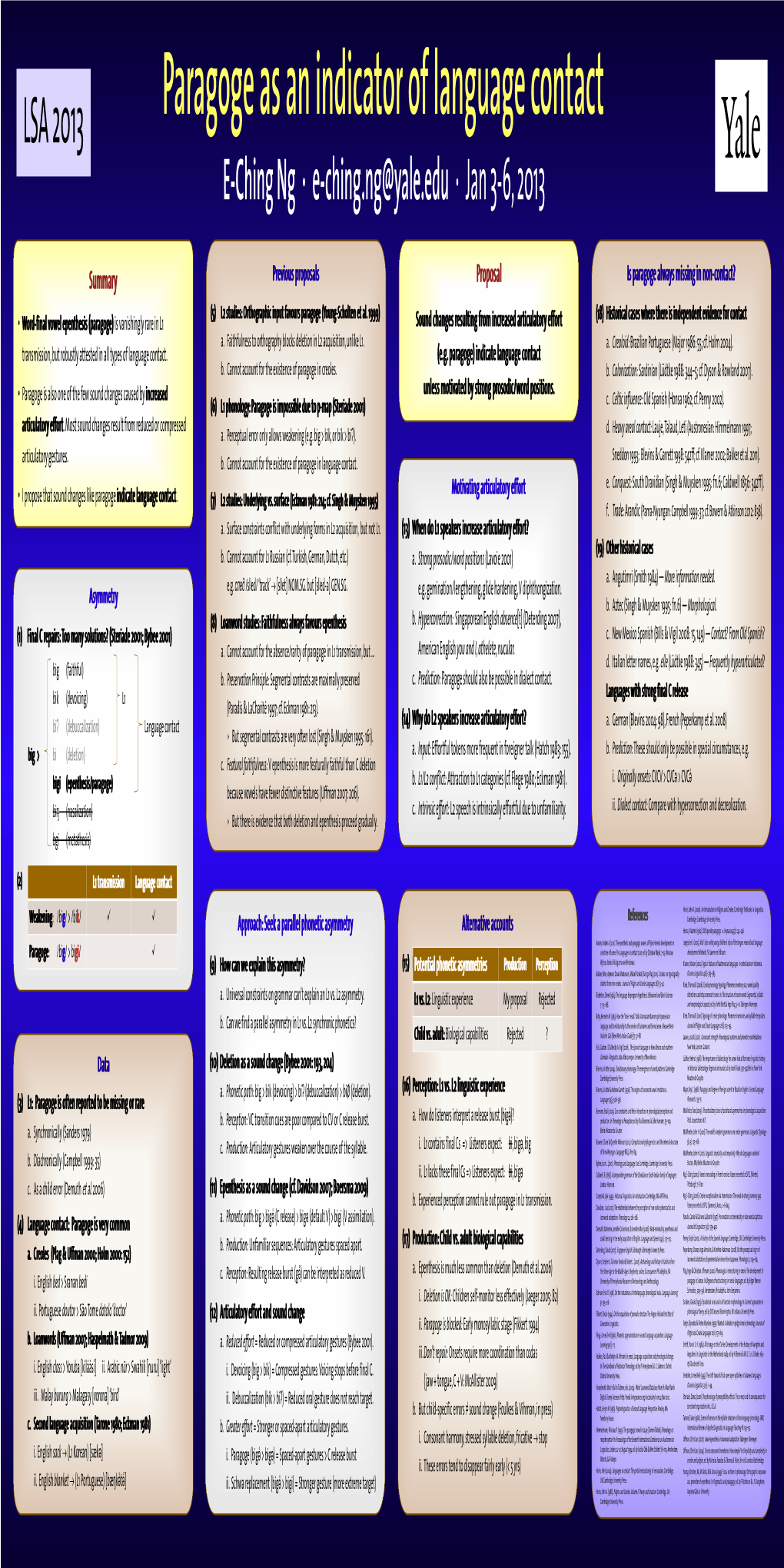

Paragoge SPCL

When language contact doesn’t favor paragoge E-Ching Ng · Yale University Society for Pidgin and Creole Linguistics, 4–5 Jan 2013 [email protected] The paragoge asymmetry (word-final epenthesis) (1) Creole exceptionalism a. Bioprogram hypothesis: Simplification ← Child L1 acquisition (Bickerton 1984) b. Creole prototype hypothesis: Simplification ← Adult L2 acquisition (McWhorter 2001, 2011) c. Proposed here: Diachronic difference ← Adult L2 acquisition (cf. Ng 2011a, 2011b) (2) Final C repairs L1 transmission Language contact a. Weakening • big > bik > biʔ > biØ V V b. Paragoge • big > bigi V Data (3) Non-contact: Paragoge is often reported to be missing or rare a. Synchronically (missing: Sanders 1979; Steriade 2001) b. Diachronically (rare: Campbell 1999: 35) c. Child speech (rare: Demuth et al . 2006) (4) a. Creoles: Paragoge is common i. English big > Sranan bigi (Wilner 2003: 124) ii. English school > Solomon Islands Pidgin sukulu (Jourdan & Keesing 1997: 413) iii. English walk > Kromanti waka (Bilby 1983: 42) iv. Portuguese doutor > São Tome dotolo ‘doctor’ (Lipski 2000) v. Dutch pompoen > Berbice Dutch Creole pampuna ‘pumpkin’ (Singh & Muysken 1995) b. Loanwords too (Uffman 2007; Haspelmath & Tadmor 2009) i. English class > Yoruba [kíláàsi] ii. German Arbeit > Japanese [arubaito] ‘part-time job’ iii. Arabic nūr > Swahili [nuru] ‘light’ iv. Malay burung > Malagasy [vorona] ‘bird’ c. L2 acquisition too (Tarone 1980; Eckman 1981) i. English sack → (L1 Korean) [sækI] ii. English blanket → (L1 Portuguese) [bæŋkI̊tI̊] Previous proposals (5) L2 acquisition: Orthographic input favours paragoge (Young-Scholten et al. 1999) a. Faithfulness to orthography blocks deletion in L2 acquisition, favouring paragoge b. But this does not account for the existence of paragoge in creoles.