Scottish Industrial History Vol 5.2 1982

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SS Kurland First World War Site Report

Forgotten Wrecks of the SS Kurland First World War Site Report 2018 FORGOTTEN WRECKS OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR SS KURLAND SITE REPORT Table of Contents i Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................................ 3 ii Copyright Statement ........................................................................................................................ 3 iii List of Figures .................................................................................................................................. 3 1. Project Background ............................................................................................................................. 4 2. Methodology ....................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Desk Based Research .................................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Geophysical Survey Data ............................................................................................................... 4 2.3 Associated Artefacts ..................................................................................................................... 5 3. Vessel Biography: SS Kurland .............................................................................................................. 5 3.1 Vessel Type and Build .................................................................................................................. -

Arbourmaster's

THE Harbourmaster’sHOUSE A HISTORY www.theharbourmastershouse.co.uk The Harbourmaster’s House has been standing at the foot of Hot Pot Wynd at Dysart harbour since around 1840, taking the place of a much earlier Shore House which was demolished in 1796. 02 Looking at the peaceful harbour today with its fleet of small boats, it’s hard to imagine what it was like when it was an important and very busy commercial port: when tall-masted sailing ships from foreign ports were packed so tightly that it was possible to walk across their decks from one side of the dock to the other. There was a brisk import and export trade with the Low Countries and the Baltic, with the tall ships bringing in a wide and varied amount of goods and taking away locally produced coal, salt and other items. ˆ Dysart harbour today Harbourmaster’s House c.1860 ˇ 03 Although Dysart was recorded as a incoming ship came in and allocated port as early as 1450, there was no real their berths, and put them into position harbour, only a jetty in the bay opposite in the inner dock and harbour. He also the houses at Pan Ha’. This gradually had to supervise the working of the fell into disrepair, but the foundation dock gates, and collect the harbour stones can still be seen at low water dues which went to Dysart Town at the largest spring tides three or four Council (before the amalgamation with times a year. The present harbour was Kirkcaldy in 1930) towards the upkeep begun in the early 17th century when of the harbour. -

Point of Entry

DESIGNATED POINTS OF ENTRY FOR PLANT HEALTH CONTROLLED PLANTS/ PLANT PRODUCTS AND FORESTRY MATERIAL POINT OF ENTRY CODE PORT/ ADDRESS DESIGNATED POINT OF ENTRY AIRPORT FOR: ENGLAND Avonmouth AVO P The Bristol Port Co, St Andrew’s House, Plants/plant products & forestry St Andrew’s Road, Avonmouth , Bristol material BS11 9DQ Baltic Wharf LON P Baltic Distribution, Baltic Wharf, Wallasea, Forestry material Rochford, Essex, SS4 2HA Barrow Haven IMM P Barrow Haven Shipping Services, Old Ferry Forestry material Wharf, Barrow Haven, Barrow on Humber, North Lincolnshire, DN19 7ET Birmingham BHX AP Birmingham International Airport, Birmingham, Plants/plant products B26 3QJ Blyth BLY P Blyth Harbour Commission, Port of Blyth, South Plants/plant products & forestry Harbour, Blyth, Northumberland, NE24 3PB material Boston BOS P The Dock, Boston, Lincs, PE21 6BN Forestry material Bristol BRS AP Bristol Airport, Bristol, BS48 3DY Plants/plant products & forestry material Bromborough LIV P Bromborough Stevedoring & Forwarding Ltd., Forestry material Bromborough Dock, Dock Road South, Bromborough, Wirral, CH62 4SF Chatham (Medway) MED P Convoys Wharf, No 8 Berth, Chatham Docks, Forestry Material Gillingham, Kent, ME4 4SR Coventry Parcels Depot CVT P Coventry Overseas Mail Depot, Siskin Parkway Plants/plant products & forestry West, Coventry, CV3 4HX material Doncaster/Sheffield Robin DSA AP Robin Hood Airport Doncaster, Sheffield, Plants/plant products & forestry Hood Airport Heyford House, First Avenue, material Doncaster, DN9 3RH Dover Cargo Terminal, -

The Rate and Direction of Inventive Activity Revisited

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: The Rate and Direction of Inventive Activity Revisited Volume Author/Editor: Josh Lerner and Scott Stern, editors Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-47303-1; 978-0-226-47303-1 (cloth) Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/lern11-1 Conference Date: September 30 - October 2, 2010 Publication Date: March 2012 Chapter Title: The Rate and Direction of Invention in the British Industrial Revolution: Incentives and Institutions Chapter Authors: Ralf R. Meisenzahl, Joel Mokyr Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c12364 Chapter pages in book: (p. 443 - 479) 9 The Rate and Direction of Invention in the British Industrial Revolution Incentives and Institutions Ralf R. Meisenzahl and Joel Mokyr 9.1 Introduction The Industrial Revolution was the fi rst period in which technological progress and innovation became major factors in economic growth. There is by now general agreement that during the seventy years or so traditionally associated with the Industrial Revolution, there was little economic growth as traditionally measured in Britain, but that in large part this was to be expected.1 The sectors in which technological progress occurred grew at a rapid rate, but they were small in 1760, and thus their effect on growth was limited at fi rst (Mokyr 1998, 12– 14). Yet progress took place in a wide range of industries and activities, not just in cotton and steam. A full description of the range of activities in which innovation took place or was at least attempted cannot be provided here, but inventions in some pivotal industries such as iron and mechanical engineering had backward linkages in many more traditional industries. -

X61 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

X61 bus time schedule & line map X61 Edinburgh - Dundee or St Andrews View In Website Mode The X61 bus line (Edinburgh - Dundee or St Andrews) has 5 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Dundee City Centre: 6:05 AM - 4:50 PM (2) Edinburgh: 5:45 AM - 8:20 PM (3) Kennoway: 5:50 PM (4) Kirkcaldy: 4:55 PM - 5:55 PM (5) Leven: 6:50 PM - 11:25 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest X61 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next X61 bus arriving. Direction: Dundee City Centre X61 bus Time Schedule 92 stops Dundee City Centre Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 7:40 AM - 4:50 PM Monday 6:05 AM - 4:50 PM Bus Station, Edinburgh 4 Multrees Walk, Edinburgh Tuesday 6:05 AM - 4:50 PM Princes Street (Scott Mon.), Edinburgh Wednesday 6:05 AM - 4:50 PM 53 Princes Street, Edinburgh Thursday 6:05 AM - 4:50 PM Princes Street (West), Edinburgh Friday 6:05 AM - 4:50 PM 107 Princes Street, Edinburgh Saturday 6:40 AM - 4:50 PM Queensferry Street, West End 10B Queensferry Street, Edinburgh Learmonth Terrace, Orchard Brae 34 Buckingham Terrace, Edinburgh X61 bus Info Direction: Dundee City Centre Craigleith Road, Craigleith Stops: 92 118 Queensferry Road, Edinburgh Trip Duration: 176 min Line Summary: Bus Station, Edinburgh, Princes Telford Road, Blackhall Street (Scott Mon.), Edinburgh, Princes Street (West), 37 Hillhouse Road, Edinburgh Edinburgh, Queensferry Street, West End, Learmonth Terrace, Orchard Brae, Craigleith Road, Craigleith, Hillpark Steps, Blackhall Telford Road, Blackhall, Hillpark Steps, Blackhall, 401 Queensferry -

Industrial Biography

Industrial Biography Samuel Smiles Industrial Biography Table of Contents Industrial Biography.................................................................................................................................................1 Samuel Smiles................................................................................................................................................1 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER I. IRON AND CIVILIZATION..................................................................................................2 CHAPTER II. EARLY ENGLISH IRON MANUFACTURE....................................................................16 CHAPTER III. IRON−SMELTING BY PIT−COAL−−DUD DUDLEY...................................................24 CHAPTER IV. ANDREW YARRANTON.................................................................................................33 CHAPTER V. COALBROOKDALE IRON WORKS−−THE DARBYS AND REYNOLDSES..............42 CHAPTER VI. INVENTION OF CAST STEEL−−BENJAMIN HUNTSMAN........................................53 CHAPTER VII. THE INVENTIONS OF HENRY CORT.........................................................................60 CHAPTER VIII. THE SCOTCH IRON MANUFACTURE − Dr. ROEBUCK DAVID MUSHET..........69 CHAPTER IX. INVENTION OF THE HOT BLAST−−JAMES BEAUMONT NEILSON......................76 CHAPTER X. MECHANICAL INVENTIONS AND INVENTORS........................................................82 -

The Rate and Direction of Invention in the British Industrial Revolution: Incentives and Institutions

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES THE RATE AND DIRECTION OF INVENTION IN THE BRITISH INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION: INCENTIVES AND INSTITUTIONS Ralf Meisenzahl Joel Mokyr Working Paper 16993 http://www.nber.org/papers/w16993 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 April 2011 Prepared for the 50th anniversary conference in honor of The Rate and Direction of Inventive Activity, ed. Scott Stern and Joshua Lerner. The authors acknowledge financial support from the Kauffman Foundation and the superb research assistance of Alexandru Rus. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect views of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System or those of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2011 by Ralf Meisenzahl and Joel Mokyr. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. The Rate and Direction of Invention in the British Industrial Revolution: Incentives and Institutions Ralf Meisenzahl and Joel Mokyr NBER Working Paper No. 16993 April 2011 JEL No. N13,N73,O31,O34,O43 ABSTRACT During the Industrial Revolution technological progress and innovation became the main drivers of economic growth. But why was Britain the technological leader? We argue that one hitherto little recognized British advantage was the supply of highly skilled, mechanically able craftsmen who were able to adapt, implement, improve, and tweak new technologies and who provided the micro inventions necessary to make macro inventions highly productive and remunerative. -

Wealth, Waste, and Alienation: Growth and Decline in the Connellsville Coke Industry

1 The Foundations of the Industry The Nature, Use, and Early Development of Coke in the United States Coke is the residue produced when great heat is applied to coal kept out of direct contact with air. The process is conducted either by cov- ering the coal with a more or less impermeable layer or, more effec- tively, by enclosing it in an oven. Volatiles are driven off, leaving a product that is largely carbon. There are various types of coke. That made as a byproduct of gas production is derived from coals fairly high in volatiles and is rapidly processed in retorts at relatively low temperatures. The resulting coke is dull, spongy, and burns readily. In contrast, low-volatile coals produce insufficient gas to complete the coking process. Between these extremes are the so-called caking coals. “Burned” at higher temperature and with a long continued heat, the best caking coals—which should also have only a low ash and sulfur content—produce a coke much harder and denser than gas coke, a coke that is strong, fibrous, and silver-gray in color and has a semi- metallic luster. Its hardness means it is resistant to abrasion and therefore free from fine particles. This kind of coke is porous, its structure vesicular—that is, having minute holes formed by the release of the gases that it once contained. Because it is admirably suited for use as a fuel in furnaces provided with a strong draught, this product of a limited, special group of coals with these highly distinc- tive properties and striking appearance is known as metallurgical coke. -

Blast Furnace

Blast furnace From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search Blast furnace in Sestao, Spain. The actual furnace itself is inside the centre girderwork. A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce metals, generally iron. In a blast furnace, fuel and ore are continuously supplied through the top of the furnace, while air (sometimes with oxygen enrichment) is blown into the bottom of the chamber, so that the chemical reactions take place throughout the furnace as the material moves downward. The end products are usually molten metal and slag phases tapped from the bottom, and flue gases exiting from the top of the furnace. Blast furnaces are to be contrasted with air furnaces (such as reverberatory furnaces), which were naturally aspirated, usually by the convection of hot gases in a chimney flue. According to this broad definition, bloomeries for iron, blowing houses for tin, and smelt mills for lead, would be classified as blast furnaces. However, the term has usually been limited to those used for smelting iron ore to produce pig iron, an intermediate material used in the production of commercial iron and steel. Contents [hide] • 1 History o 1.1 China o 1.2 Ancient World elsewhere o 1.3 Medieval Europe o 1.4 Early modern blast furnaces: origin and spread o 1.5 Coke blast furnaces o 1.6 Modern furnaces • 2 Modern process • 3 Chemistry • 4 See also • 5 References o 5.1 Notes o 5.2 Bibliography • 6 External links [edit] History Blast furnaces existed in China from about the 5th century BC, and in the West from the High Middle Ages. -

OTHER USERS and MATERIAL ASSETS (INFRASTRUCTURE, OTHER NATURAL RESOURCES) A3h.1 INTRODUCTION

Offshore Energy SEA APPENDIX 3h – OTHER USERS AND MATERIAL ASSETS (INFRASTRUCTURE, OTHER NATURAL RESOURCES) A3h.1 INTRODUCTION The coasts and seas of the UK are intensively used for numerous activities of local, regional and national importance including coastally located power generators and process industries, port operations, shipping, oil and gas production, fishing, aggregate extraction, military practice, as a location for submarine cables and pipelines and for sailing, racing and other recreation. At a local scale, activities as diverse as saltmarsh, dune or machair grazing, seaweed harvesting or bait collection may be important. These activities necessarily interact at the coast and offshore and spatial conflicts can potentially arise. A key consideration of this SEA is the potential for plan elements to interact with other users and material assets, the nature and location of which are described below. A3h.2 PORTS AND SHIPPING A3h.2.1 Commercial ports UK ports are located around the coast, with their origin based on historic considerations including, principally, advantageous geography (major and other ports are indicated in Figure A3h.1 below). In 2007, some 582 million tonnes (Mt) of freight traffic was handled by UK ports, a slight decrease (ca. 2Mt) from that handled in 2006. The traffic handled in ports in England, Scotland and Wales was very similar in 2006 and 2007, differing by less than 0.5%. However, ports in Northern Ireland handled 2.5% less traffic in 2007, compared to in 2006. Over the last ten years, since 1997, inward traffic to UK ports has increased by 21% and outward traffic has decreased by 15%. -

Notice of Situation of Polling Stations Kirkcaldy Constituency Scottish Parliament Election on Thursday 6 May 2021

Notice of Situation of Polling Stations Kirkcaldy Constituency Scottish Parliament Election on Thursday 6 May 2021 Polling Station Polling Place and address District Part of Register (First and last Street) Number Code 142 BURNTISLAND PARISH CHURCH HALL, WEST 201IAA Voters in streets etc commencing with ABBOTS VIEW LEVEN STREET, BURNTISLAND, KY3 9DX to WEST LEVEN STREET inclusive 143 TOLL COMMUNITY CENTRE, KIRKCALDY ROAD, 202IAB Voters in streets etc commencing with ABERDOUR BURNTISLAND, KY3 9HA ROAD to CROMWELL ROAD inclusive 144 TOLL COMMUNITY CENTRE, KIRKCALDY ROAD, 202IAB Voters in streets etc commencing with DALLAS BURNTISLAND, KY3 9HA AVENUE to HERIOT GARDENS inclusive 145 TOLL COMMUNITY CENTRE, KIRKCALDY ROAD, 202IAB Voters in streets etc commencing with INCHGARVIE BURNTISLAND, KY3 9HA AVENUE to LOCHIES ROAD inclusive 146 TOLL COMMUNITY CENTRE, KIRKCALDY ROAD, 202IAB Voters in streets etc commencing with LONSDALE BURNTISLAND, KY3 9HA CRESCENT to KY2 5XA, KY2 5XB, KY2 5XD, KY2 5XE, KY2 5XF, KY3 0AS inclusive 147 AUCHTERTOOL VILLAGE HALL, MAIN STREET, 203IAC Voters in streets etc commencing with KY2 5XW to AUCHTERTOOL, KY2 5XW KY2 5UZ, KY2 5XA inclusive 148 KINGHORN COMMUNITY CENTRE, ROSSLAND 204IAD Voters in streets etc commencing with KY2 5UU, KY3 PLACE, KINGHORN, KY3 9SS 9YG to EASTGATE inclusive 149 KINGHORN COMMUNITY CENTRE, ROSSLAND 204IAD Voters in streets etc commencing with GLAMIS ROAD PLACE, KINGHORN, KY3 9SS to ORCHARD TERRACE inclusive 150 KINGHORN COMMUNITY CENTRE, ROSSLAND 204IAD Voters in streets etc commencing with -

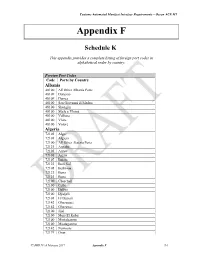

Appendix F – Schedule K

Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 Appendix F Schedule K This appendix provides a complete listing of foreign port codes in alphabetical order by country. Foreign Port Codes Code Ports by Country Albania 48100 All Other Albania Ports 48109 Durazzo 48109 Durres 48100 San Giovanni di Medua 48100 Shengjin 48100 Skele e Vlores 48100 Vallona 48100 Vlore 48100 Volore Algeria 72101 Alger 72101 Algiers 72100 All Other Algeria Ports 72123 Annaba 72105 Arzew 72105 Arziw 72107 Bejaia 72123 Beni Saf 72105 Bethioua 72123 Bona 72123 Bone 72100 Cherchell 72100 Collo 72100 Dellys 72100 Djidjelli 72101 El Djazair 72142 Ghazaouet 72142 Ghazawet 72100 Jijel 72100 Mers El Kebir 72100 Mestghanem 72100 Mostaganem 72142 Nemours 72179 Oran CAMIR V1.4 February 2017 Appendix F F-1 Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 72189 Skikda 72100 Tenes 72179 Wahran American Samoa 95101 Pago Pago Harbor Angola 76299 All Other Angola Ports 76299 Ambriz 76299 Benguela 76231 Cabinda 76299 Cuio 76274 Lobito 76288 Lombo 76288 Lombo Terminal 76278 Luanda 76282 Malongo Oil Terminal 76279 Namibe 76299 Novo Redondo 76283 Palanca Terminal 76288 Port Lombo 76299 Porto Alexandre 76299 Porto Amboim 76281 Soyo Oil Terminal 76281 Soyo-Quinfuquena term. 76284 Takula 76284 Takula Terminal 76299 Tombua Anguilla 24821 Anguilla 24823 Sombrero Island Antigua 24831 Parham Harbour, Antigua 24831 St. John's, Antigua Argentina 35700 Acevedo 35700 All Other Argentina Ports 35710 Bagual 35701 Bahia Blanca 35705 Buenos Aires 35703 Caleta Cordova 35703 Caleta Olivares 35703 Caleta Olivia 35711 Campana 35702 Comodoro Rivadavia 35700 Concepcion del Uruguay 35700 Diamante 35700 Ibicuy CAMIR V1.4 February 2017 Appendix F F-2 Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 35737 La Plata 35740 Madryn 35739 Mar del Plata 35741 Necochea 35779 Pto.