SPARC Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Superh RISC Engine SH-1/SH-2

SuperH RISC Engine SH-1/SH-2 Programming Manual September 3, 1996 Hitachi America Ltd. Notice When using this document, keep the following in mind: 1. This document may, wholly or partially, be subject to change without notice. 2. All rights are reserved: No one is permitted to reproduce or duplicate, in any form, the whole or part of this document without Hitachi’s permission. 3. Hitachi will not be held responsible for any damage to the user that may result from accidents or any other reasons during operation of the user’s unit according to this document. 4. Circuitry and other examples described herein are meant merely to indicate the characteristics and performance of Hitachi’s semiconductor products. Hitachi assumes no responsibility for any intellectual property claims or other problems that may result from applications based on the examples described herein. 5. No license is granted by implication or otherwise under any patents or other rights of any third party or Hitachi, Ltd. 6. MEDICAL APPLICATIONS: Hitachi’s products are not authorized for use in MEDICAL APPLICATIONS without the written consent of the appropriate officer of Hitachi’s sales company. Such use includes, but is not limited to, use in life support systems. Buyers of Hitachi’s products are requested to notify the relevant Hitachi sales offices when planning to use the products in MEDICAL APPLICATIONS. Introduction The SuperH RISC engine family incorporates a RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Computer) type CPU. A basic instruction can be executed in one clock cycle, realizing high performance operation. A built-in multiplier can execute multiplication and addition as quickly as DSP. -

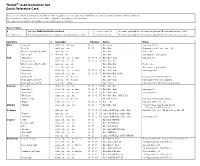

Thumb® 16-Bit Instruction Set Quick Reference Card

Thumb® 16-bit Instruction Set Quick Reference Card This card lists all Thumb instructions available on Thumb-capable processors earlier than ARM®v6T2. In addition, it lists all Thumb-2 16-bit instructions. The instructions shown on this card are all 16-bit in Thumb-2, except where noted otherwise. All registers are Lo (R0-R7) except where specified. Hi registers are R8-R15. Key to Tables § See Table ARM architecture versions. <loreglist+LR> A comma-separated list of Lo registers. plus the LR, enclosed in braces, { and }. <loreglist> A comma-separated list of Lo registers, enclosed in braces, { and }. <loreglist+PC> A comma-separated list of Lo registers. plus the PC, enclosed in braces, { and }. Operation § Assembler Updates Action Notes Move Immediate MOVS Rd, #<imm> N Z Rd := imm imm range 0-255. Lo to Lo MOVS Rd, Rm N Z Rd := Rm Synonym of LSLS Rd, Rm, #0 Hi to Lo, Lo to Hi, Hi to Hi MOV Rd, Rm Rd := Rm Not Lo to Lo. Any to Any 6 MOV Rd, Rm Rd := Rm Any register to any register. Add Immediate 3 ADDS Rd, Rn, #<imm> N Z C V Rd := Rn + imm imm range 0-7. All registers Lo ADDS Rd, Rn, Rm N Z C V Rd := Rn + Rm Hi to Lo, Lo to Hi, Hi to Hi ADD Rd, Rd, Rm Rd := Rd + Rm Not Lo to Lo. Any to Any T2 ADD Rd, Rd, Rm Rd := Rd + Rm Any register to any register. Immediate 8 ADDS Rd, Rd, #<imm> N Z C V Rd := Rd + imm imm range 0-255. -

Readingsample

Embedded Robotics Mobile Robot Design and Applications with Embedded Systems Bearbeitet von Thomas Bräunl Neuausgabe 2008. Taschenbuch. xiv, 546 S. Paperback ISBN 978 3 540 70533 8 Format (B x L): 17 x 24,4 cm Gewicht: 1940 g Weitere Fachgebiete > Technik > Elektronik > Robotik Zu Inhaltsverzeichnis schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. CENTRAL PROCESSING UNIT . he CPU (central processing unit) is the heart of every embedded system and every personal computer. It comprises the ALU (arithmetic logic unit), responsible for the number crunching, and the CU (control unit), responsible for instruction sequencing and branching. Modern microprocessors and microcontrollers provide on a single chip the CPU and a varying degree of additional components, such as counters, timing coprocessors, watchdogs, SRAM (static RAM), and Flash-ROM (electrically erasable ROM). Hardware can be described on several different levels, from low-level tran- sistor-level to high-level hardware description languages (HDLs). The so- called register-transfer level is somewhat in-between, describing CPU compo- nents and their interaction on a relatively high level. We will use this level in this chapter to introduce gradually more complex components, which we will then use to construct a complete CPU. With the simulation system Retro [Chansavat Bräunl 1999], [Bräunl 2000], we will be able to actually program, run, and test our CPUs. -

Reverse Engineering X86 Processor Microcode

Reverse Engineering x86 Processor Microcode Philipp Koppe, Benjamin Kollenda, Marc Fyrbiak, Christian Kison, Robert Gawlik, Christof Paar, and Thorsten Holz, Ruhr-University Bochum https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity17/technical-sessions/presentation/koppe This paper is included in the Proceedings of the 26th USENIX Security Symposium August 16–18, 2017 • Vancouver, BC, Canada ISBN 978-1-931971-40-9 Open access to the Proceedings of the 26th USENIX Security Symposium is sponsored by USENIX Reverse Engineering x86 Processor Microcode Philipp Koppe, Benjamin Kollenda, Marc Fyrbiak, Christian Kison, Robert Gawlik, Christof Paar, and Thorsten Holz Ruhr-Universitat¨ Bochum Abstract hardware modifications [48]. Dedicated hardware units to counter bugs are imperfect [36, 49] and involve non- Microcode is an abstraction layer on top of the phys- negligible hardware costs [8]. The infamous Pentium fdiv ical components of a CPU and present in most general- bug [62] illustrated a clear economic need for field up- purpose CPUs today. In addition to facilitate complex and dates after deployment in order to turn off defective parts vast instruction sets, it also provides an update mechanism and patch erroneous behavior. Note that the implementa- that allows CPUs to be patched in-place without requiring tion of a modern processor involves millions of lines of any special hardware. While it is well-known that CPUs HDL code [55] and verification of functional correctness are regularly updated with this mechanism, very little is for such processors is still an unsolved problem [4, 29]. known about its inner workings given that microcode and the update mechanism are proprietary and have not been Since the 1970s, x86 processor manufacturers have throughly analyzed yet. -

Pipeliningpipelining

ChapterChapter 99 PipeliningPipelining Jin-Fu Li Department of Electrical Engineering National Central University Jungli, Taiwan Outline ¾ Basic Concepts ¾ Data Hazards ¾ Instruction Hazards Advanced Reliable Systems (ARES) Lab. Jin-Fu Li, EE, NCU 2 Content Coverage Main Memory System Address Data/Instruction Central Processing Unit (CPU) Operational Registers Arithmetic Instruction and Cache Logic Unit Sets memory Program Counter Control Unit Input/Output System Advanced Reliable Systems (ARES) Lab. Jin-Fu Li, EE, NCU 3 Basic Concepts ¾ Pipelining is a particularly effective way of organizing concurrent activity in a computer system ¾ Let Fi and Ei refer to the fetch and execute steps for instruction Ii ¾ Execution of a program consists of a sequence of fetch and execute steps, as shown below I1 I2 I3 I4 I5 F1 E1 F2 E2 F3 E3 F4 E4 F5 Advanced Reliable Systems (ARES) Lab. Jin-Fu Li, EE, NCU 4 Hardware Organization ¾ Consider a computer that has two separate hardware units, one for fetching instructions and another for executing them, as shown below Interstage Buffer Instruction fetch Execution unit unit Advanced Reliable Systems (ARES) Lab. Jin-Fu Li, EE, NCU 5 Basic Idea of Instruction Pipelining 12 3 4 5 Time I1 F1 E1 I2 F2 E2 I3 F3 E3 I4 F4 E4 F E Advanced Reliable Systems (ARES) Lab. Jin-Fu Li, EE, NCU 6 A 4-Stage Pipeline 12 3 4 567 Time I1 F1 D1 E1 W1 I2 F2 D2 E2 W2 I3 F3 D3 E3 W3 I4 F4 D4 E4 W4 D: Decode F: Fetch Instruction E: Execute W: Write instruction & fetch operation results operands B1 B2 B3 Advanced Reliable Systems (ARES) Lab. -

The RISC-V Compressed Instruction Set Manual

The RISC-V Compressed Instruction Set Manual Version 1.7 Warning! This draft specification will change before being accepted as standard, so implementations made to this draft specification will likely not conform to the future standard. Andrew Waterman, Yunsup Lee, David Patterson, Krste Asanovi´c CS Division, EECS Department, University of California, Berkeley fwaterman|yunsup|pattrsn|[email protected] May 28, 2015 This document is also available as Technical Report UCB/EECS-2015-157. 2 RISC-V Compressed ISA V1.7 1.1 Introduction This excerpt from the RISC-V User-Level ISA Specification describes the current draft proposal for the RISC-V standard compressed instruction set extension, named \C", which reduces static and dynamic code size by adding short 16-bit instruction encodings for common integer operations. The C extension can be added to any of the base ISAs (RV32I, RV64I, RV128I), and we use the generic term \RVC" to cover any of these. Typically, over half of the RISC-V instructions in a program can be replaced with RVC instructions, resulting in greater than a 25% code-size reduction. Section 1.7 describes a possible extended set of instructions for RVC, for which we would like your opinion. Please send your comments to the isa-dev mailing list at [email protected]. 1.2 Overview RVC uses a simple compression scheme that offers shorter 16-bit versions of common 32-bit RISC-V instructions when: • the immediate or address offset is small, or • one of the registers is the zero register (x0) or the ABI stack pointer (x2), or • the destination register and the first source register are identical, or • the registers used are the 8 most popular ones. -

Powerpc User Instruction Set Architecture Book I Version 2.01

PowerPC User Instruction Set Architecture Book I Version 2.01 September 2003 Manager: Joe Wetzel/Poughkeepsie/IBM Technical Content: Ed Silha/Austin/IBM Cathy May/Watson/IBM Brad Frey/Austin/IBM The following paragraph does not apply to the United Kingdom or any country or state where such provisions are inconsistent with local law. The specifications in this manual are subject to change without notice. This manual is provided “AS IS”. Interna- tional Business Machines Corp. makes no warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied, including, but not limited to, the implied warranties of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose. International Business Machines Corp. does not warrant that the contents of this publication or the accompanying source code examples, whether individually or as one or more groups, will meet your requirements or that the publication or the accompanying source code examples are error-free. This publication could include technical inaccuracies or typographical errors. Changes are periodically made to the information herein; these changes will be incorporated in new editions of the publication. Address comments to IBM Corporation, Internal Zip 9630, 11400 Burnett Road, Austin, Texas 78758-3493. IBM may use or distribute whatever information you supply in any way it believes appropriate without incurring any obligation to you. The following terms are trademarks of the International Business Machines Corporation in the United States and/or other countries: IBM PowerPC RISC/System 6000 POWER POWER2 POWER4 POWER4+ IBM System/370 Notice to U.S. Government Users—Documentation Related to Restricted Rights—Use, duplication or disclosure is subject to restrictions set fourth in GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corporation. -

UM0434 E200z3 Powerpc Core Reference Manual

UM0434 e200z3 PowerPC core Reference manual Introduction The primary objective of this user’s manual is to describe the functionality of the e200z3 embedded microprocessor core for software and hardware developers. This book is intended as a companion to the EREF: A Programmer's Reference Manual for Freescale Book E Processors (hereafter referred to as EREF). Book E is a PowerPC™ architecture definition for embedded processors that ensures binary compatibility with the user-instruction set architecture (UISA) portion of the PowerPC architecture as it was jointly developed by Apple, IBM, and Motorola (referred to as the AIM architecture). This document distinguishes among the three levels of the architectural and implementation definition, as follows: ● The Book E architecture—Book E defines a set of user-level instructions and registers that are drawn from the user instruction set architecture (UISA) portion of the AIM definition PowerPC architecture. Book E also includes numerous supervisor-level registers and instructions as they were defined in the AIM version of the PowerPC architecture for the virtual environment architecture (VEA) and the operating environment architecture (OEA). Because the operating system resources (such as the MMU and interrupts) defined by Book E differ greatly from those defined by the AIM architecture, Book E introduces many new registers and instructions. ● Freescale Book E implementation standards (EIS)—In many cases, the Book E architecture definition provides a general framework, leaving specific details up to the implementation. To ensure consistency among its Book E implementations, Freescale has defined implementation standards that provide an additional layer of architecture between Book E and the actual devices. -

The ARM Instruction Set Architecture

EE382N-4 Embedded Systems Architecture The ARM Instruction Set Architecture Mark McDermott With help from our good friends at ARM Fall 2008 8/22/2008 EE382N-4 Embedded Systems Architecture Main features of the ARM Instruction Set All instructions are 32 bits long. Most instructions execute in a single cycle. Most instructions can be conditionally executed. A load/store architecture – Data processing instructions act only on registers • Three operand format • Combined ALU and shifter for high speed bit manipulation – Specific memory access instructions with powerful auto‐indexing addressing modes. • 32 bit and 8 bit data types – and also 16 bit data types on ARM Architecture v4. • Flexible multiple register load and store instructions Instruction set extension via coprocessors Very dense 16‐bit compressed instruction set (Thumb) 8/22/2008 2 EE382N-4 Embedded Systems Architecture Coprocessors – Up to 16 coprocessors can be defined – Expands the ARM instruction set – Each coprocessor can have up to 16 private registers of any reasonable size – Load‐store architecture 3 EE382N-4 Embedded Systems Architecture Thumb Thumb is a 16‐bit instruction set – Optimized for code density from C code – Improved performance form narrow memory – Subset of the functionality of the ARM instruction set Core has two execution states –ARM and Thumb – Switch between them using BX instruction Thumb has characteristic features: – Most Thumb instruction are executed unconditionally – Many Thumb data process instruction use a 2‐address format – Thumb instruction -

Instruction Set Architecture

Instruction Set Architecture EE3376 1 –Adapted from notes from BYU ECE124 Topics to Cover… l MSP430 ISA l MSP430 Registers, ALU, Memory l Instruction Formats l Addressing Modes l Double Operand Instructions l Single Operand Instructions l Jump Instructions l Emulated Instructions – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TI_MSP430 2 –Adapted from notes from BYU ECE124 Levels of Transformation –Problems –Algorithms – C Instructions –Language (Program) –Programmable –Assembly Language – MSP 430 ISA –Machine (ISA) Architecture –Computer Specific –Microarchitecture –Manufacturer Specific –Circuits –Devices 3 –Adapted from notes from BYU ECE124 Instruction Set Architecture l The computer ISA defines all of the programmer-visible components and operations of the computer – memory organization l address space -- how may locations can be addressed? l addressibility -- how many bits per location? – register set (a place to store a collection of bits) l how many? what size? how are they used? – instruction set l Opcodes (operation selection codes) l data types (data types: byte or word) l addressing modes (coding schemes to access data) l ISA provides all information needed for someone that wants to write a program in machine language (or translate 4 from a high-level language to machine language). –Adapted from notes from BYU ECE124 MSP430 Instruction Set Architecture l MSP430 CPU specifically designed to allow the use of modern programming techniques, such as: – the computation of jump addresses – data processing in tables – use of high-level languages such as C. l 64KB memory space with 16 16-bit registers that reduce fetches to memory. l Implements RISC architecture with 27 instructions and 7 addressing modes. -

Branch Instructions

Sparc Assembly Directives&Branching CS217 Sparc AssemblyReview CCode Assemblycode x=a+5000; seta,%i1 ld[%i1],%g1 set5000,%g2 ? add%g1,%g2,%g1 setx,%i1 st %g1,[%i1] 1 StilltoLearn • Howdo“definevariables” • Howtoimplementcontrolstructures • Howtodefineandcallfunctions • Otherdetails AAsssseemmbblleerrDDiirreeccttiivveess AssemblerDirectives • Identifysections • Allocate/initializememory • Makesymbolsexternallyvisible 2 IdentifyingSections • Text(.section“.text”) 0 Containscode(instructions) OS Defaultsection 0x2000 Text • Read-OnlyData(.section“.rodata”) Data Containsconstants BSS • Read-WriteData(.section“.data”) Heap Containsuser-initializedglobalvariables • BSS(.section“.bss”) Blockstartingsymbol Containszero-initializedglobalvariables Stack 0xffffffff Sections(cont) • Eachsectionhasownlocationcounter Locationcounterisupdatedwhenassembler processesdirectiveorinstruction add and sethi T or e x text_lc ld t 0 1 D data_lc a t a 3 Allocatingmemory • Incrementlocationcounterbynbytes .skip nbytes .section“.bss” var1:.skip16 .section“.data” var2:.skip4 Initializingmemory • Incrementlocationcounterandinitializedata .bytebyteval1[,byteval2...] .halfhalfval1[,halfval2...] .wordwordval1[,wordval2...] .section“.data” sethi T sum:.word0 or e x ld t .section“.text” setsum,%o0 D ld[%o0],%i1 a sum: 0 t a 4 InitializingASCIIData • Specialdirectivesforasciidata .byte150,145,154,154,157,0 .ascii“hello” .byte0 .asciz “hello” MakingSymbolsExternallyVisible • Markvariablesasglobal .global .section“.data” .align4 .globalmonth month:.word jan, feb,mar, apr,may, -

Mpcxxx Instruction Set

Freescale Semiconductor, Inc. Freescale Semiconductor, Inc. MPCxxx Instruction Set This chapter lists the MPCxxx instruction set in alphabetical order by mnemonic. Note that each entry includes the instruction formats and a quick reference ‘legend’ that provides such information as the level(s) of the PowerPC architecture in which the instruction may be found—user instruction set architecture (UISA), virtual environment architecture (VEA), and operating environment architecture (OEA); and the privilege level of the instruction—user- or supervisor-level (an instruction is assumed to be user-level unless nc... the legend specifies that it is supervisor-level); and the instruction formats. The format diagrams show, horizontally, all valid combinations of instruction fields. Note that the architecture specification refers to user-level and supervisor-level as problem state and privileged state, respectively. Instruction Formats Instructions are four bytes long and word-aligned, so when instruction addresses are presented to the processor (as in branch instructions) the two low-order bits are ignored. Similarly, whenever the processor develops an instruction address, its two low-order bits are zero. Bits 0–5 always specify the primary opcode. Many instructions also have an extended opcode. The remaining bits of the instruction contain one or more fields for the different instruction formats. Some instruction fields are reserved or must contain a predefined value as shown in the individual instruction layouts. If a reserved field does not have all bits cleared, or if a field that must contain a particular value does not contain that value, the instruction form is invalid. Split-Field Notation Some instruction fields occupy more than one contiguous sequence of bits or occupy a contiguous sequence of bits used in permuted order.