The Rhetorical Discourse Surrounding Female Intersex Athletes Victoria T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Expectations of a New Administration Busy Year Ahead for Stetson

mm A Stetson Vol. 16 No. 1 (USPS 990-560) Fall 1987 m CUPOLA Expectations of a new administration Help us preserve Stetson's great heritage—this is cal leaves. A total of 20 grants will be made each what Stetson University's eighth president, Dr. H. year. Douglas Lee, is asking of alumni and friends of the Dr. Lee also revealed that the university's fourth institution. president and only alumnus to hold that position, In turn, he pledges to try to live up to their expec was responsible for the fund which supports the tations: to keep the quality of the academic experi McEniry Award for Excellence in Teaching, awarded ence high, and to support the faculty as "the heart annually at Stetson. Noting that Dr. Edmunds "was and soul of Stetson." and is Stetson . the grand old man of the univer Dr. Lee outlined what he believes the university's sity," he recalled an admonition Dr. Edmunds has various constituencies expect of him, and what he given him: "Young man, don't you ever forget that will expect of them, during his first address to fac the key to Stetson University is its faculty . they ulty and students at the 105th convocation Sept. 2 in are the heart and lifeblood of this university." the Forest of Arden. He urged students to "pursue your humanity . "We do have a great heritage, and we must pre understand who you are as a person . and develop serve it," Dr. Lee declared. Whatever we have given the competency and skill to do a worthwhile task, in the past, we must continue to give in the future. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 75-3121

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Intersex, Discrimination and the Healthcare Environment – a Critical Investigation of Current English Law

Intersex, Discrimination and the Healthcare Environment – a Critical Investigation of Current English Law Karen Jane Brown Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements of London Metropolitan University for the Award of PhD Year of final Submission: 2016 Table of Contents Table of Contents......................................................................................................................i Table of Figures........................................................................................................................v Table of Abbreviations.............................................................................................................v Tables of Cases........................................................................................................................vi Domestic cases...vi Cases from the European Court of Human Rights...vii International Jurisprudence...vii Tables of Legislation.............................................................................................................viii Table of Statutes- England…viii Table of Statutory Instruments- England…x Table of Legislation-Scotland…x Table of European and International Measures...x Conventions...x Directives...x Table of Legislation-Australia...xi Table of Legislation-Germany...x Table of Legislation-Malta...x Table of Legislation-New Zealand...xi Table of Legislation-Republic of Ireland...x Table of Legislation-South Africa...xi Objectives of Thesis................................................................................................................xii -

The Olympic 100M Sprint

Exploring the winning data: the Olympic 100 m sprint Performances in athletic events have steadily improved since the Olympics first started in 1896. Chemists have contributed to these improvements in a number of ways. For example, the design of improved materials for clothing and equipment; devising and monitoring the best methods for training for particular sports and gaining a better understanding of how energy is released from our food so ensure that athletes get the best diet. Figure 1 Image of a gold medallist in the Olympic 100 m sprint. Year Winner (Men) Time (s) Winner (Women) Time (s) 1896 Thomas Burke (USA) 12.0 1900 Francis Jarvis (USA) 11.0 1904 Archie Hahn (USA) 11.0 1906 Archie Hahn (USA) 11.2 1908 Reginald Walker (S Africa) 10.8 1912 Ralph Craig (USA) 10.8 1920 Charles Paddock (USA) 10.8 1924 Harold Abrahams (GB) 10.6 1928 Percy Williams (Canada) 10.8 Elizabeth Robinson (USA) 12.2 1932 Eddie Tolan (USA) 10.38 Stanislawa Walasiewick (POL) 11.9 1936 Jessie Owens (USA) 10.30 Helen Stephens (USA) 11.5 1948 Harrison Dillard (USA) 10.30 Fanny Blankers-Koen (NED) 11.9 1952 Lindy Remigino (USA) 10.78 Majorie Jackson (USA) 11.5 1956 Bobby Morrow (USA) 10.62 Betty Cuthbert (AUS) 11.4 1960 Armin Hary (FRG) 10.32 Wilma Rudolph (USA) 11.3 1964 Robert Hayes (USA) 10.06 Wyomia Tyus (USA) 11.2 1968 James Hines (USA) 9.95 Wyomia Tyus (USA) 11.08 1972 Valeriy Borzov (USSR) 10.14 Renate Stecher (GDR) 11.07 1976 Hasely Crawford (Trinidad) 10.06 Anneqret Richter (FRG) 11.01 1980 Allan Wells (GB) 10.25 Lyudmila Kondratyeva (USA) 11.06 1984 Carl Lewis (USA) 9.99 Evelyn Ashford (USA) 10.97 1988 Carl Lewis (USA) 9.92 Florence Griffith-Joyner (USA) 10.62 1992 Linford Christie (GB) 9.96 Gail Devers (USA) 10.82 1996 Donovan Bailey (Canada) 9.84 Gail Devers (USA) 10.94 2000 Maurice Green (USA) 9.87 Eksterine Thanou (GRE) 11.12 2004 Justin Gatlin (USA) 9.85 Yuliya Nesterenko (BLR) 10.93 2008 Usain Bolt (Jam) 9.69 Shelly-Ann Fraser (Jam) 10.78 2012 Usain Bolt (Jam) 9.63 Shelly-Ann Fraser (Jam) 10.75 Exploring the wining data: 100 m sprint| 11-16 Questions 1. -

Babe Didrikson Zaharias Super-Athlete

2 MORE THAN 150 YEARS OF WOMEN’S HISTORY March is Women’s History Month. The Women’s Rights Movement started in Seneca Falls, New York, with the first Women’s Rights Convention in 1848.Out of the convention came a declaration modeled upon the Declaration of Independence, written by a woman named Elizabeth Cady THE WOMEN WE HONOR Stanton. They worked inside and outside of their homes. business and labor; science and medicine; sports and It demanded that women be given They pressed for social changes in civil rights, the peace exploration; and arts and entertainment. all the rights and privileges that belong movement and other important causes. As volunteers, As you read our mini-biographies of these women, they did important charity work in their communities you’ll be asked to think about what drove them toward to them as citizens of the United States. and worked in places like libraries and museums. their achievements. And to think how women are Of course, it was many years before Women of every race, class and ethnic background driven to achieve today. And to consider how women earned all the rights the have made important contributions to our nation women will achieve in the future. Seneca Falls convention demanded. throughout its history. But sometimes their contribution Because women’s history is a living story, our list of has been overlooked or underappreciated or forgotten. American women includes women who lived “then” American women were not given Since 1987, our nation has been remembering and women who are living—and achieving—”now.” the right to vote until 1920. -

RARITA Ownshi

RARITA owNSHI Every Reader The Beacon of the Beacon should keep in mind that Invites news articles and expressions the advertisements carry as much V of opinions on timely subjects from our "punch" as the news article*- Every readers. We welcome all such contri- advertiser has a message tor the read- butions and will publish them as far ers and uses this medium because he as possible. But, It Is very Important knows the readers desire to keep that all correspondence be signed by abreast of every advant*e« *B the writer. know what's COing on. (and Woodbridge Journal) Raritan Township Office: Fords Office: Cor. Main St. & Route 25 465 New Brunswick Ave. "The Voice of the Raritan Bay District" VOL. VI.— No. 21 >ORDS AND RARITAN TOWNSHIP FRIDAY MORNING, JULY 31, 1936. PRICE THREE CENTS WILL ELIMINATE A Short, Short Story SCHOOL BODY TO WOMAN ESCAPES TID BIT BUSINESS An Open Letter About Raritan's Relief , 9 RAMBLING RARITAN TOWNSHIP.— July 31, 1936. TALMADGE ROAD REPAIR MOST OF IS MANIPULATED Here's a triple-short story in DEATH IN JUMP Stadium Commission, REPORTER Wocdbridge, New Jersej. resolution form: "Whereas the Dear Brother Members: CRADE GROSSING Township of Raritan finds it- OLDER BUILDINGS Says ^== BY COMMISSION self unable to entirely meet FROMJDSTORY Of course you know I'm still for you and all that stuff. Fellas BIDS FOR WORK TO BE RE- such responsibilities (the relief TO EXPEND ABOUT $3,000 One of the more prom- GETS LIQUOR* APPLICATION but I'm wondering how. it was that we came about giving the load) because of Its loss of rev- MORNING BLAZE FORCES people of Fords, Keasbey and Hopelawn the impression that we inent Fords couples will CEIVED AUGUST 17. -

Medicine, Sport and the Body: a Historical Perspective

Carter, Neil. "Medicine, Sport and the Female Body." Medicine, Sport and the Body: A Historical Perspective. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2012. 151–172. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 30 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781849662062.ch-007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 30 September 2021, 07:48 UTC. Copyright © Neil Carter 2012. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 7 Medicine, Sport and the Female Body Introduction In 2007, tucked away in the Daily Telegraph’s sports round, it was reported that the Indian middle-distance runner, Santhi Soundarajan, was in hospital following a suicide attempt. The previous year she had been stripped of the silver medal she won in the 800 metres at the Asian Games. The reason: she had failed a gender test. 1 It is not known if the two events were linked but two years later the issue of gender testing would be given greater prominence following the victory of the South African Caster Semenya in the women’s 800 metres at the 2009 World Athletics Championships in Berlin. As questions were raised over the exact status of her sex, people asked whether it was ‘fair’ that she should be competing against other female athletes. It is ironic, as Vanessa Heggie has pointed out, that whereas there are probably hundreds of genetic variations that lead to ‘unfair’ advantages in sport, ‘only those associated with gender are used to exclude or disqualify athletes’. -

Reading Counts

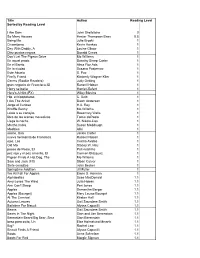

Title Author Reading Level Sorted by Reading Level I Am Sam John Shefelbine 0 So Many Houses Hester Thompson Bass 0.5 Being Me Julie Broski 1 Crisantemo Kevin Henkes 1 Day With Daddy, A Louise Gikow 1 Diez puntos negros Donald Crews 1 Don't Let The Pigeon Drive Mo Willems 1 En aquel prado Dorothy Sharp Carter 1 En el Barrio Alma Flor Ada 1 En la ciudad Susana Pasternac 1 Este Abuelo S. Paz 1 Firefly Friend Kimberly Wagner Klier 1 Germs (Rookie Readers) Judy Oetting 1 gran negocio de Francisca, El Russell Hoban 1 Harry se baña Harriet Ziefert 1 Here's A Hint (FX) Wiley Blevins 1 Hip, el hipopótamo C. Dzib 1 I Am The Artist! Dawn Anderson 1 Jorge el Curioso H.A. Rey 1 Knuffle Bunny Mo Willems 1 Léale a su conejito Rosemary Wells 1 libro de las arenas movedizas Tomie dePaola 1 Llega la noche W. Nikola-Lisa 1 Martha habla Susan Meddaugh 1 Modales Aliki 1 noche, Una Jackie Carter 1 nueva hermanita de Francisca Russell Hoban 1 ojos, Los Cecilia Avalos 1 Old Mo Stacey W. Hsu 1 paseo de Rosie, El Pat Hutchins 1 pez rojo y el pez amarillo, El Carmen Blázquez 1 Pigeon Finds A Hot Dog, The Mo Willems 1 Sam and Jack (FX) Sloan Culver 1 Siete conejitos John Becker 1 Springtime Addition Jill Fuller 1 We All Fall For Apples Emmi S. Herman 1 Alphabatics Suse MacDonald 1.1 Amy Loves The Wind Julia Hoban 1.1 Ann Can't Sleep Peri Jones 1.1 Apples Samantha Berger 1.1 Apples (Bourget) Mary Louise Bourget 1.1 At The Carnival Kirsten Hall 1.1 Autumn Leaves Gail Saunders-Smith 1.1 Bathtime For Biscuit Alyssa Capucilli 1.1 Beans Gail Saunders-Smith 1.1 Bears In The Night Stan and Jan Berenstain 1.1 Berenstain Bears/Big Bear, Sma Stan Berenstain 1.1 beso para osito, Un Else Holmelund Minarik 1.1 Big? Rachel Lear 1.1 Biscuit Finds A Friend Alyssa Capucilli 1.1 Boots Anne Schreiber 1.1 Boots For Red Margie Sigman 1.1 Box, The Constance Andrea Keremes 1.1 Brian Wildsmith's ABC Brian Wildsmith 1.1 Brown Rabbit's Shape Book Alan Baker 1.1 Bubble Trouble Mary Packard 1.1 Bubble Trouble (Rookie Reader) Joy N. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 75-23,153

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. Yi necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Extensions of Remarks

13532 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS June 5, 1979 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS SPECIAL OLYMPICS ACTIVITY FEA talking with ·Elvin Hayes of the Washington Speaker, I would like to take this oppor TURED IN COLMAN McCARTHY Bullets or a Special Olympian who takes two minutes for the 100-yard dash, I would go tunity to bring to the attention of my ARTICLE with the young sprinter. Last year, I ran a colleagues the impending retirement few miles with Blll Rodgers, the distance from education of Fred V. Pankow, su HON. JENNINGS RANDOLPH man who has won three Boston marathons; perintendent of Lanse Creuse School but I had more of a thrill when I did a lap District for the past 20 years. OF WEST VIRGINIA with a retarded child. Having spent the last 30 years involved IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES I call him retarded, which 1s the label in teaching and education, Mr. Pankow Tuesday, June 5, 1979 most of us use, only because his limitations are conveniently definable. The IQ scores will typically remain in education, re • Mr. RANDOLPH. Mr. President, the and reports of "the child experts" categorize tiring to continue work on his doctorate Washington Post recently published an the flaws and so let us, the seemingly healthy, degree at Wayne State University. article by Colman McCarthy on the Spe go on about our business of normalcy. Mr. Pankow's dedication to his work, cial Olympics program. Special Olympics But if the poet Wallace Stevens is right, the school district, its parents and teach that "We are all hot with the imperfect," provides to more than a million retarded then what has been happening through the ers is legendary. -

A Study of Sports and the Implications of Women's Participation in Them in Modern Society

A STUDY OF SPORTS AND THE IMPLICATIONS OF WOMEN'S PARTICIPATION IN THEM IN MODERN SOCIETY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By LAURA ELIZABETH KRATZ, B. S., A. M The Ohio State University 1958 Approved by Adviser Department of Physical Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writer wishes to express her appreciation to Doctor Bruce L. Bennett for his assistance in the preparation of this manuscript and to Mrs. John R. Kinzer and other members of the Statistics Laboratory of the Mathematics Department for their assistance with the calculations involved in the study. ii CONTENTS Chapter Page I INTRODUCTION............... .•............. 1 The Problem and Its Importance............. 1 The Changing American Character............ ^ Patterns of Conformity in American Character ........................... 7 Play as a Vital Part of Civilization........ 10 Cultural Definitions of Work and P l a y ....... 13 Women's Increasing Participation in Sports............................ 15 II THE STATUS OF WOMEN IN AMERICAN CULTURE....... 19 Women Exercise a Cultural Focal Influence............................ 21 The Influence of Technological Changes....... 22 The Influence of Soeio-Psychological Factors.................. 28 Women's Organizations and their Influence............................ ^1 Women's Present Work Ro l e ................. ^3 Advances in Sports Lines Parallel Women's Progress in Other Areas ........ *+8 Summary: The Status of American Women Today ........................... 50 III A GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF WOMEN'S PARTICIPATION IN SPORTS .................. 52 The Most Influential Factors in Women's Broader Participation .................. 53 Women's Skill in Participation Becomes Greater at Four Different Levels.......... 63 Participation on the Family and School Levels is More Accepted than Participation on Other Levels ........... -

Faye Glenn Abdellah 1919 - • As a Nurse Researcher Transformed Nursing Theory, Nursing Care, and Nursing Education

Faye Glenn Abdellah 1919 - • As a nurse researcher transformed nursing theory, nursing care, and nursing education • Moved nursing practice beyond the patient to include care of families and the elderly • First nurse and first woman to serve as Deputy Surgeon General Bella Abzug 1920 – 1998 • As an attorney and legislator championed women’s rights, human rights, equality, peace and social justice • Helped found the National Women’s Political Caucus Abigail Adams 1744 – 1818 • An early feminist who urged her husband, future president John Adams to “Remember the Ladies” and grant them their civil rights • Shaped and shared her husband’s political convictions Jane Addams 1860 – 1935 • Through her efforts in the settlement movement, prodded America to respond to many social ills • Received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931 Madeleine Korbel Albright 1937 – • First female Secretary of State • Dedicated to policies and institutions to better the world • A sought-after global strategic consultant Tenley Albright 1934 – • First American woman to win a world figure skating championship; triumphed in figure skating after overcoming polio • First winner of figure skating’s triple crown • A surgeon and blood plasma researcher who works to eradicate polio around the world Louisa May Alcott 1832 – 1888 • Prolific author of books for American girls. Most famous book is Little Women • An advocate for abolition and suffrage – the first woman to register to vote in Concord, Massachusetts in 1879 Florence Ellinwood Allen 1884 – 1966 • A pioneer in the legal field with an amazing list of firsts: The first woman elected to a judgeship in the U.S. First woman to sit on a state supreme court.