Mongolica Pragensia 13-2.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Herever Possible

Published by Department of Information and International Relations (DIIR) Central Tibetan Administration Dharamshala-176215 H.P. India Email: [email protected] www.tibet.net Copyright © DIIR 2018 First edition: October 2018 1000 copies ISBN-978-93-82205-12-8 Design & Layout: Kunga Phuntsok / DIIR Printed at New Delhi: Norbu Graphics CONTENTS Foreword------------------------------------------------------------------1 Chapter One: Burning Tibet: Self-immolation Protests in Tibet---------------------5 Chapter Two: The Historical Status of Tibet-------------------------------------------37 Chapter Three: Human Rights Situation in Tibet--------------------------------------69 Chapter Four: Cultural Genocide in Tibet--------------------------------------------107 Chapter Five: The Tibetan Plateau and its Deteriorating Environment---------135 Chapter Six: The True Nature of Economic Development in Tibet-------------159 Chapter Seven: China’s Urbanization in Tibet-----------------------------------------183 Chapter Eight: China’s Master Plan for Tibet: Rule by Reincarnation-------------197 Chapter Nine: Middle Way Approach: The Way Forward--------------------------225 FOREWORD For Tibetans, information is a precious commodity. Severe restric- tions on expression accompanied by a relentless disinformation campaign engenders facts, knowledge and truth to become priceless. This has long been the case with Tibet. At the time of the publication of this report, Tibet has been fully oc- cupied by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) for just five months shy of sixty years. As China has sought to develop Tibet in certain ways, largely economically and in Chinese regions, its obsessive re- strictions on the flow of information have only grown more intense. Meanwhile, the PRC has ready answers to fill the gaps created by its information constraints, whether on medieval history or current growth trends. These government versions of the facts are backed ever more fiercely as the nation’s economic and military power grows. -

2008 UPRISING in TIBET: CHRONOLOGY and ANALYSIS © 2008, Department of Information and International Relations, CTA First Edition, 1000 Copies ISBN: 978-93-80091-15-0

2008 UPRISING IN TIBET CHRONOLOGY AND ANALYSIS CONTENTS (Full contents here) Foreword List of Abbreviations 2008 Tibet Uprising: A Chronology 2008 Tibet Uprising: An Analysis Introduction Facts and Figures State Response to the Protests Reaction of the International Community Reaction of the Chinese People Causes Behind 2008 Tibet Uprising: Flawed Tibet Policies? Political and Cultural Protests in Tibet: 1950-1996 Conclusion Appendices Maps Glossary of Counties in Tibet 2008 UPRISING IN TIBET CHRONOLOGY AND ANALYSIS UN, EU & Human Rights Desk Department of Information and International Relations Central Tibetan Administration Dharamsala - 176215, HP, INDIA 2010 2008 UPRISING IN TIBET: CHRONOLOGY AND ANALYSIS © 2008, Department of Information and International Relations, CTA First Edition, 1000 copies ISBN: 978-93-80091-15-0 Acknowledgements: Norzin Dolma Editorial Consultants Jane Perkins (Chronology section) JoAnn Dionne (Analysis section) Other Contributions (Chronology section) Gabrielle Lafitte, Rebecca Nowark, Kunsang Dorje, Tsomo, Dhela, Pela, Freeman, Josh, Jean Cover photo courtesy Agence France-Presse (AFP) Published by: UN, EU & Human Rights Desk Department of Information and International Relations (DIIR) Central Tibetan Administration (CTA) Gangchen Kyishong Dharamsala - 176215, HP, INDIA Phone: +91-1892-222457,222510 Fax: +91-1892-224957 Email: [email protected] Website: www.tibet.net; www.tibet.com Printed at: Narthang Press DIIR, CTA Gangchen Kyishong Dharamsala - 176215, HP, INDIA ... for those who lost their lives, for -

Two Approaches to Non-‐Sectarianism in Twentieth Century Ti

Highlighting Unity: Two Approaches to Non-Sectarianism in Twentieth Century Tibet Adam Pearcey In the late 19th and early 20th centuries there were attempts – apparently connected with the so-called “Ris med Movement” – to strengthen the scholastic traditions of non- dGe lugs schools in Eastern Tibet. These efforts included the establishment of dozens of scriptural colleges (bshad grwa) throughout the region, and the printing and dissemination of works by the Sa skya scholar, Go rams pa bSod nams seng ge (1429– 1489) and the Nyingma polymath, ’Ju Mi pham (1846–1912). The texts of these two influential philosophers, complete with their notorious criticisms of mainstream dGe lugs pa thought, came to represent the orthodox viewpoint for followers of their respective traditions within many newly founded scriptural colleges. These developments were not without controversy, however, and inspired much debate and polemical exchange. In commenting upon this period and its key figures, some modern scholars have questioned how the strengthening and promotion of individual philosophical traditions could be regarded as non-sectarian. Yet, in spite of this, there is no question that ’Ju Mi pham and the publishers of Go rams pa’s writings continue to be associated with the Ris med ideal. In this paper I will explore the views of two writers who took a different approach to inter-sectarian (and intra-sectarian) discourse during this same period of Tibetan history and who both lived in the mGo log region of Eastern Tibet. These authors aimed less at differentiating and strengthening rival doctrines, and more at highlighting their underlying unity or compatibility. -

Uprising in Tibet 10 March-30 April 2008

Uprising in Tibet 10 March-30 April 2008 CITIES AND COUNTIES WHERE PROTESTS DOCUMENTED BY TIBET WATCH OCCURRED Lanzhou Rebkong Tsigor Thang Labrang Mangra Tsoe Luchu Machu Dzoge Marthang Ngaba Serthar Kandze Drango Tawu Bathang Lhasa 28 CHARLES SQUARE, LONDON, N1 6HT, U.K. PHONE: +44 (0)20 7324 4608 FAX: +44 (0)20 7324 4606 INTRODUCTION This report is a summary of information gathered and received by Tibet Watch concerning protests in Tibet which occurred during March and April 2008. It is not a comprehensive record of all the protests that took place in Tibet, but only of those incidents which Tibet Watch has received reliable information about. Indeed, it is likely that there were many incidents of protest across Tibet which have remain unreported due to the tight security restrictions and communications lockdown imposed. It is for the same reason that it has since been extremely difficult to find out any further information about the documented events other than what is provided here. Although some of the information in this document relies on single sources, the news we have received has, where possible, been corroborated or checked against information received by other news gathering organizations. CONTENTS Kandze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture ................................................................................................ 3 Bathang County (Ch: Batang) .............................................................................................. 3 Drango County (Ch: Luhuo) ................................................................................................ -

The White Pill: Perceptions and Experiences of Efficacy of a Popular Tibetan Medicine in Multiethnic Rebgong

asian medicine �0 (�0�5) ���–�48 brill.com/asme The White Pill: Perceptions and Experiences of Efficacy of a Popular Tibetan Medicine in Multiethnic Rebgong Nianggajia Qinghai Nationalities University, University of Oslo, Norway [email protected] Abstract In this paper, I address the local perceptions and experiences of efficacy among pro- ducers and patients of a popular Tibetan medicine in multiethnic Rebgong, a regional hub of Tibetan medicine in Qinghai Province, PRC. Known as the ‘White Pill’—Rikar in Tibetan, Jiebaiwan in Chinese—it is often taken directly without prescription for stomach and digestive disorders that are common among Tibetan, Han, and Hui patients. I will examine the White Pill’s classical formula and how different local pro- ducers in Rebgong explain what makes their own White Pill so effective and popu- lar. Based on interviews with patients of different cultural backgrounds, my research shows that the popularity of this Tibetan medicine is increasing among both Tibetans and non-Tibetans in Rebgong during the past decade. This is probably due to the new ways of producing the White Pill by specifically targeting common digestive disorders, which often and previously have been experienced as not being satisfactorily treated by Chinese biomedical pharmaceuticals. In particular, Rikar or Jiebaiwan is locally known and experienced to be simply the most effective treatment for stomach and digestive disorders without having side effects. Keywords Tibetan medicine – White Pill – Rikar – Jiebaiwan – multiethnic use – Rebgong (Tongren) © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, ���6 | doi �0.��63/�5734��8-��34�Downloaded35� from Brill.com09/25/2021 08:54:18PM via free access 222 Nianggajia Rebgong—A Hub of Tibetan Medicine in Amdo In the past decade ‘Tibetan medicine’ (Tib. -

Establishing Lineage Legitimacy and Building Labrang Monastery As “The Source of Dharma”: Jikmed Wangpo (1728–1791) Taking the Helm

religions Article Establishing Lineage Legitimacy and Building Labrang Monastery as “the Source of Dharma”: Jikmed Wangpo (1728–1791) Taking the Helm Rinchen Dorje The Center for Research on Ethnic Minorities in Northwest China, The College of History and Culture, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, China; [email protected] Abstract: The eighteenth century witnessed the continuity of Geluk growth in Amdo from the preceding century. Geluk inspiration and legacy from Central Tibet and the accompanying political patronage emanating from the Manchus, Mongols, and local Tibetans figured prominently as the engine behind the Geluk influence that swept Amdo. The Geluk rise in the region resulted from contributions made by native Geluk Buddhists. Amdo native monks are, however, rarely treated with as much attention as they deserve for cultivating extensive networks of intellectual transmission, reorienting and shaping the school’s future. I therefore propose that we approach Geluk hegemony and their broad initiatives in the region with respect to the school’s intellectual and cultural order and native Amdo Buddhist monks’ role in shaping Geluk history in Amdo and beyond in Tibet. Such a focus highlights their impact in shaping the trajectory of Geluk history in Tibet and Amdo in particular. The historical and biographical literature dealing with the life of Jikmed Wangpo affords us a rare window into the pivotal time when every effort was made to cultivate a vast network of institutions and masters across Tibet. This further spurred an institutional growth of Citation: Dorje, Rinchen. 2021. Buddhist transmission, constructing authenticity and authority thereof, as they were closely tied to Establishing Lineage Legitimacy and reincarnation lineage, intellectual traditions, and monastic institutions. -

Why Tibet Is Burning…

Why Tibet is Burning… TPI PUBLICATIONS Published by: Tibetan Policy Institute Kashag Secretariat Central Tibetan Administration Gangchen Kyishong, Dharamshala-176215 First Edition, 2013 ©TPI ISBN: 978-93-80091-35-8 Foreword As of this moment, the flames of fire raging in Tibet have consumed the lives of 98 Tibetans. This deepening crisis in Tibet is fuelled by China’s total disregard for the religious beliefs, cultural values and reasonable political aspirations of the Tibetan people. The crisis grows out of China’s political repression, cultural assimilation, economic marginalisation, social discrimination and environmental destruction in Tibet. We, the Kashag, continue to appeal not to resort to drastic actions, including self-immolations, because life is precious. Unfortunately, self-immolations continue to persist in Tibet. It is therefore our sacred duty to support and amplify the aspirations of Tibetan people: the return of His Holiness the Dalai Lama to his homeland and freedom for Tibet. The Central Tibetan Administration believes that collective action by the international community can persuade Chinese leaders to put in place lenient policies that respect the aspirations of the Tibetan people—and at the same time, do not undermine the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the People’s Republic of China. With this goal in mind, we offer this report to global citizens and leaders. It presents in-depth examination and analysis of the policy areas that relentlessly rob Tibetans of their culture and language, and undermine their chosen way of life. These four critical policy areas include interference in and suppression of both religion and language, the forced removal of Tibetan nomads from the grasslands and the population transfer policy that moves Chinese to the Tibetan Plateau and reduces Tibetans to an increasingly disenfranchised and marginalised minority in their own land. -

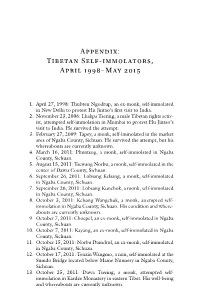

Appendix: Tibetan Self-Immolators, April 1998–May 2015

Appendix: Tibetan Self-immolators, April 1998–May 2015 1. April 27, 1998: Thubten Ngodrup, an ex-monk, self-immolated in New Delhi to protest Hu Jintao’s first visit to India. 2. November 23, 2006: Lhakpa Tsering, a male Tibetan rights activ- ist, attempted self-immolation in Mumbai to protest Hu Jintao’s visit to India. He survived the attempt. 3. February 27, 2009: Tapey, a monk, self-immolated in the market area of Ngaba County, Sichuan. He survived the attempt, but his whereabouts are currently unknown. 4. March 16, 2011: Phuntsog, a monk, self-immolated in Ngaba County, Sichuan. 5. August 15, 2011: Tsewang Norbu, a monk, self-immolated in the center of Dawu County, Sichuan. 6. September 26, 2011: Lobsang Kelsang, a monk, self-immolated in Ngaba County, Sichuan. 7. September 26, 2011: Lobsang Kunchok, a monk, self-immolated in Ngaba County, Sichuan. 8. October 3, 2011: Kelsang Wangchuk, a monk, attempted self- immolation in Ngaba County, Sichuan. His condition and where- abouts are currently unknown. 9. October 7, 2011: Choepel, an ex-monk, self-immolated in Ngaba County, Sichuan. 10. October 7, 2011: Kayang, an ex-monk, self-immolated in Ngaba County, Sichuan. 11. October 15, 2011: Norbu Damdrul, an ex-monk, self-immolated in Ngaba County, Sichuan. 12. October 17, 2011: Tenzin Wangmo, a nun, self-immolated at the Sumdo Bridge located below Mame Nunnery in Ngaba County, Sichuan. 13. October 25, 2011: Dawa Tsering, a monk, attempted self- immolation in Kardze Monastery in eastern Tibet. His well-being and whereabouts are currently unknown. 152 Appendix 14. -

2012 August to November

VOICE - TWA Newsletter 2 August 2012 - November 2012 Chronology of Self-immolation incidents inside Tibet For our August to November 2012 issue of the quarterly news- letter, Voice, we have continued to publish the chronology of self-immolation incidents inside Tibet from the last newsletter (April-July). The number goes from 50 to 76. This account of self-immolation incidents is our humble way of recognizing the highest sacrifi ces made by the martyrs and also to show our respect and solidarity with them and make their sac- rifi ces known to the world. 50. Name-Lobsang Kalsang Age-18 Gender-M Self-Immolated on-27 Aug,12 From-Kirti Monastery, Ngapa Status-Deceased obsang Kalsang and his cousin Lobsang LDamchoe, both teens from Ngapa, self immolated on 27th August, 2012 near the eastern gate of Kirti monastery. Lobsang Kalsang was 18 years old and a monk from the Kirti monastery. Witnesses saw him walking with fl ames shooting from his body before he collapsed on the ground. Chinese security personnel extinguished the fl ames and took both of them initially to the hospital in Ngapa town and later moved them to a hospital in Barkham. According to the Kirti monks in exile, both of them died in the hospital. 1 VOICE - TWA Newsletter 51. Name-Lobsang Damchoe Age-17 Gender-M Self-Immolated on-27 August,12 From-Ngapa, Former Monk of Kirti Monasetery Status-Deceased 7-year-old Lobsang Damchoe, a cousin of Lobsang Kalsang, 1was a former monk from Kirti monastery. He set himself on fi re on 27 August,12 with his cousin near the eastern gate of Kirti monastery. -

Annual Report 2016, 24 February 2017

Human Rights Situation in Tibet Annual Report 2016 Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................... 5 FREEDOM OF OPINION AND EXPRESSION ....................................................................... 7 I. Legal Standards ...................................................................................................... 7 A. The Johannesburg Principles.............................................................................. 8 B. Chinese Law ...................................................................................................... 9 II. Mass Surveillance Program ................................................................................... 11 III. Directive Criminalizes Freedom of Expression ..................................................... 12 IV. Crackdown on Self-immolation Continues .......................................................... 13 V. Detention of Peaceful Protesters ........................................................................... 15 VI. Silencing the Bloggers .......................................................................................... 17 VII. Conclusion .......................................................................................................... 20 RIGHT TO PRIVACY ................................................................................................................ 21 I. Legal Standards ................................................................................................... -

Abstracts Pp. 1-151

13th Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies Sunday 21st July - Saturday 27th July 2013 Abstracts Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia Mongolian Academy of Sciences - National University of Mongolia 1 ‘Who is a Real Monk’? Monastic Practice and Ideas of Lineage in Ulaanbaatar Saskia Abrahms-Kavunenko Opinions about what constitutes monastic life reflect broader questions about lineage and tradition amongst Buddhi- sts in Ulaanbaatar. Partly due to the ‘domestication’ of religion during the socialist period, the majority of the Mongol Sangha do not follow full monastic vows. In opposition to this, new ideas about monastic discipline are being imported by global Buddhist organisations and are influencing lay perspectives of Mongol monastics. Both global and local forms of Buddhism argue that they are following ‘tradition’ in various ways. After 1990 many old men, who had been part of monasteries as young men before the socialist period, once again identified as lamas, shaved their heads and started to wear robes. These lamas had been forced to disrobe during the 1930s and when they reclaimed their role as lamas many already headed a household. Some of these lamas had been practicing in secret during the socialist period and they saw no contradiction in being a Buddhist lama and maintaining a family. These lamas have taken on students who, following their teachers’ examples, have a girlfriend or a wife and practice as lamas. Additionally, due to a lack of temple resources, these lamas cannot live inside the temple where they work and have to ‘return’ to society after working hours like any other householder. As local Buddhist practitioners became public lamas, international Buddhist organisations connected to the Tibetan diaspora came to Mongolia with the hope of ‘reforming’ and helping to spread Buddhism in Mongolia. -

Introduction to Tibetan History

བོད་དང་བོད་མིའིབདེན་པའི་ལོ་རྒྱུས་ཀི་ཉིང་ཁུ། TIBET AND ITS PEOPLE –AN ESSENCE OF TRUE HISTORY A presentation of the facts from 127 BCE to 1959; Chinese occupation of Tibet, The Middle-Way Approach, striving for a peaceful resolution on the issue of Tibet and Tibetan Democracy in Exile An Educational Supplement to Build Awareness of Tibet’s Cultural, Religious and Political History Compiled by: Kalsang Gyatso Kunor Compiler’s Note The situation in Tibet, under the Chinese Communist rule, is as grim as it was more than 60 years ago when the Chinese Communists first began their era of devastation in Tibet. As each new Tibetan generation ages without ever setting foot in Tibet, and because of my regular contacts with people from different countries, I have been urged to compile a brief factual history of Tibet that includes reliable original documents and authentic pictures from various sources. In an incident while I was working in a middle school students there ,during a project discussion, said that the “the Tibetans demanded independence from China and the Chinese government kicked them out of Tibet, “ rather than realizing that Tibet was independent and the Tibetans were asking the Chinese to leave Tibet. In a second incident, while meeting a Chinese student to help him with a class assignment, the student, without any hesitation, proclaimed “Tibet is a part of China. Tibetans peel off human beings and drink blood, but now Tibetans are very happy under the Chinese rule,” all in our introduction! I told him “I am really sorry that your government has misled you with wrong information about Tibet.