Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IBM Security Appscan Standard: User Guide Traffic Log

IBM Security AppScan Standard Version 9.0.3.11 User Guide IBM Contents Chapter 1. Introduction ........ 1 Content-Based Results view ........ 90 Product overview............. 1 Glass Box view ............ 92 Supported technologies .......... 1 Communication and Proxy view ...... 93 What's new ............... 2 HTTP Authentication view ........ 94 Contact and support information ....... 3 Test Policy view ............ 95 Test Optimization view ......... 100 Chapter 2. Installing ......... 5 Test Options view ........... 100 Privilege Escalation view ........ 103 System requirements............ 5 Malware view ............ 104 Flash Player upgrade .......... 7 Scan Expert view ........... 104 Flash Player configuration ......... 7 Advanced Configuration view....... 106 Install................. 8 Scan file structure ............ 121 Silent install .............. 8 Scan templates ............. 121 Uninstall................ 9 Predefined templates .......... 121 License ................ 9 User-Defined Scan Templates ....... 123 Load a node-locked license ........ 10 Loading scan templates ......... 123 Load a floating or token license....... 11 Editing Scan Templates ......... 123 Updates ............... 11 Changing the configuration during a scan .... 124 Temp file location ............ 12 Chapter 3. Getting started ...... 13 Chapter 5. Manual Exploring ..... 125 Using AppScan............. 125 How an automatic scan works ........ 13 Recording a Manual Explore ....... 126 Web applications vs. web services ....... 14 Exporting Manual Explore data -

JTS Users Guide, Ver 2.0 Copyright 2013 Page 2 of 265

Table of Contents 1 ABOUT THIS GUIDE .................................................................................................................... 13 1.1 WHO SHOULD USE IT ............................................................................................................... 14 1.2 TYPOGRAPHICAL CONVENTIONS ............................................................................................... 14 2 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 16 2.1 OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................................... 16 2.2 PURPOSE ................................................................................................................................ 17 2.3 SCOPE .................................................................................................................................... 17 2.4 REFERENCES .......................................................................................................................... 18 2.5 GLOSSARY AND TERMINOLOGY ................................................................................................. 18 3 JTS SYSTEM DESCRIPTION ...................................................................................................... 21 3.1 KEY FEATURES ........................................................................................................................ 21 3.2 ENVIRONMENT ........................................................................................................................ -

IBM Security Appscan Standard: User Guide Traffic Log

IBM Security AppScan Standard Version 9.0.3.12 User Guide IBM Contents Chapter 1. Introduction ........ 1 Content-Based Results view ........ 91 Product overview............. 1 Glass Box view ............ 94 Supported technologies .......... 1 Communication and Proxy view ...... 95 What's new ............... 2 HTTP Authentication view ........ 96 Contact and support information ....... 3 Test Policy view ............ 97 Test Optimization view ......... 102 Chapter 2. Installing ......... 5 Test Options view ........... 102 Privilege Escalation view ........ 105 System requirements............ 5 Malware view ............ 106 Flash Player upgrade .......... 7 Scan Expert view ........... 106 Flash Player configuration ......... 7 Advanced Configuration view....... 108 Install................. 8 Scan file structure ............ 123 Silent install .............. 8 Scan templates ............. 123 Uninstall................ 9 Predefined templates .......... 123 License ................ 9 User-Defined Scan Templates ....... 125 Load a node-locked license ........ 10 Loading scan templates ......... 125 Load a floating or token license....... 11 Editing Scan Templates ......... 125 Updates ............... 11 Changing the configuration during a scan .... 126 Temp file location ............ 12 Chapter 3. Getting started ...... 13 Chapter 5. Manual Exploring ..... 127 Using AppScan............. 127 How an automatic scan works ........ 13 Recording a Manual Explore ....... 128 Web applications vs. web services ....... 14 Exporting Manual Explore data -

IBM Worklight V5.0.6

documentation is". user "as documentation. user offline provided IBM Worklight V5.0.6 is online Worklight the to IBM documentrefer This issues, of Experimental case In documentation is". user "as documentation. user offline provided is online Worklight the to IBM documentrefer This issues, of Experimental case In ii IBM Worklight V5.0.6 Contents Chapter 1. Starting with IBM Worklight . 1 Setting the size of the login screen for web Introducing IBM Worklight .........1 widgets...............80 System requirements for using IBM Worklight . 4 Deploying applications on iGoogle .....80 What's new ...............4 Deploying applications on Facebook .....81 What's new in IBM Worklight V5.0.6.2 .....4 Signing Adobe AIR applications ......82 What's new in IBM Worklight V5.0.6.1 .....5 Signing Windows 8 apps .........82 What's new in IBM Worklight V5.0.6 .....5 Signing Windows 7 and Vista gadgets ....83 Known limitations ............12 Embedding widgets in predefined web pages . 84 Setting up IBM Worklight Studio .......13 Development guidelines for using native API . 84 Installing IBM Worklight Studio ......14 Application Descriptor of Native API Troubleshooting IBM Worklight Studio applications for iOS ..........86 installation .............17 Client property file for iOS ........88 Upgrading IBM Worklight Studio in Eclipse . 18 Copying files of Native API applications for iOS 88 Starting IBM Worklight Studio installed with IBM Application Descriptordocumentation of Native API application Installation Manager ..........19 for Android .............89is". Starting IBM Worklight Studio installed with P2 Client property file for Android ......91 Eclipse update ............19 Copying files of Native API applications for Installing mobile specific tools .......19 Androiduser..............92 "as documentation. -

Proceedings of the 9Th Annual Federal Depository Library Conference

Proceedings of the 9^^ Annual Federal Depository Library Conference October 22-25, 2000 Library Programs Service U.S. Government Printing Office Wasliington, DC 20401 U.S. Government Printing Office Michael F. DiMario, Public Printer Superintendent of Documents Francis j. Buclcley, jr. Library Programs Service Gi! Baldwin, Director Proceedings of the 9th Annual Federal Depository Library Conference October 22 -25, 2000 Holiday Inn Rosslyn Westpark Hotel Arllington, VA Library Programs Service U.S. Government Printing Office Wasiiington, DC 20401 2001 Marian W. MacGilvray Editor Sheila McGarr Conference Coordinator Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. 2000 Federal Depository Library Conference - Proceedings Preface In what has become the Nation's premier event for Government information librarians, nearly 600 depository librarians and federal agency representatives attended the 9"" annual Federal Depository Library Conference, sponsored by GPO. The conference was held concurrently with the 57'^ meeting of the Depository Library Council to the Public Printer, in Arlington, VA. Highlights of the 3-day conference included demonstrations of Web sites from FirstGov, the Defense Technical Information Center, the U.S. Geological Survey, the U.S. Institute of Peace, the National Transportation Library, and others. GPO's ongoing transition to a more electronic FDLP, including the budget cuts to the program contained in GPO's fiscal year 2001 appropriations bill, was a primary focus of the event. The Census Bureau and STAT-USA from the Department of Commerce, the National Imagery and Mapping Agency, the Forest Service, the Department of Energy, and others presented updates on their agencies' public information activities and products. -

Accelerating Wind Turbine Blade Circularity May 2020

Subtittle if needed. If not MONTH 2018 Published in Month 2018 Accelerating Wind Turbine Blade Circularity May 2020 Accelerating Wind Turbine Blade Circularity Published May 2020 windeurope.org This report has been jointly prepared by WindEurope, Cefic and EuCIA through a collaborative cross- sector platform on wind turbine blade recycling. Notably, the report: • describes wind turbine blade structure and material composition; • highlights the expected volumes of composite waste, including wind turbine blade waste; • maps the existing regulations governing composite waste in Europe; • describes the existing recycling and recovery technologies for treating composite waste as well as innovative applications for using composite waste; and • provides recommendations for research and innovation to further enhance the circularity of wind turbine blades and design for recycling. This report is intended for general information only and, whilst its contents are provided in utmost good faith and are based on the best information currently available, is to be relied upon at the user’s own risk. No representations or warranties are made with regards to its completeness or accuracy and no liability will be accepted by the authors. We would like to thank members of WindEurope Sustainability WG for their dedicated review and input. In particular: Siemens Gamesa Renewable Energy, LM Wind Power, TPI Composites, GE Renewable Energy, MHI Vestas, Vattenfall, Vestas, Nordex, EDF Renouvelables, Engie and Ørsted. TEXT AND ANALYSIS: Marylise Schmid, WindEurope Nieves Gonzalez Ramon, Cefic Ann Dierckx, Cefic Thomas Wegman, EuCIA EDITORS: Daniel Fraile, WindEurope Colin Walsh, WindEurope DESIGN: Lin van de Velde, Drukvorm PHOTO COVER: Damon Hong MORE INFORMATION: [email protected] +32 2 213 18 11 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .....................................................................................................5 1. -

Appdna 7 And

AppDNA 7.5 and 7 2015-05-19 02:52:25 UTC © 2015 Citrix Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. Terms of Use | Trademarks | Privacy Statement Contents AppDNA 7.5 and 7 ............................................................................................ 11 AppDNA 7.5 and 7 ................................................................................ 12 About this release .......................................................................... 15 Known issues ........................................................................... 18 System requirements....................................................................... 20 Additional requirements ............................................................. 23 Virtual machine requirements ...................................................... 25 IIS and ASP.NET requirements....................................................... 26 Get started .................................................................................. 28 Quick start guide ...................................................................... 29 Import, analyze, and report ......................................................... 32 Add custom information to applications........................................... 34 Prepare for a XenDesktop 7 upgrade............................................... 38 Prepare for a move to XenDesktop 7............................................... 42 Install ......................................................................................... 46 Plan..................................................................................... -

Felipe@Ift3225 Hiver 2020 Histoire

HTML felipe@ift3225 Hiver 2020 Histoire - 1991: HTML Tags — Tim Berners Lee - 1995: HTML 2.0 - 1997: HTML 3.2 W3C - 1997: HTML 4.0 W3C - 1999: HTML 4.01 W3C Recommendation - 2000: XHTML 1.0 W3C Recommendation - 2008: HTML 5 Draft - 2014: HTML 5 W3C Recommendation - 2017: HTML 5.2 W3C Recommendation Éléments de syntaxe document XML En XHTML doctype <?xml version="1.0" encoding="iso-8859-1"?> <!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Transitional//EN" "DTD/xhtml1-transitional.dtd"> <html xml:lang="en" lang="en" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml"> <head> <title>Hello World</title> namepace </head> <body> <p>My first Web page.</p> </body> </html> un peu lourd … Avec validation <?xml version = "1.0" encoding = "utf-8" ?> <!-- file: helloworld2.html --> commentaire <!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Strict//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-strict.dtd"> <html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml"> <head> <meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" /> <title>Bonjour le monde</title> </head> - balises fermantes - encodage caractères <body> - tags en minuscule <p> Bonjour le monde. </p> - attributs entre "" <p style="text-align: center"> <a href="http://validator.w3.org/check/referer" title="Valid XHTML 1.0"> <img src="http://www.iro.umontreal.ca/~felipe/Images/button-xhtml.png" width="80" height="15" alt="Valid XHTML 1.0" /> </a> </p> </body> </html> HTML 5 <!DOCTYPE html> Indiquer la langue de la page <html lang="fr"> <head> <title>Bonjour le Monde</title> <meta charset="UTF-8"> </head> <body> Bonjour -

User's Manual for Writer2latex, Writer2bibtex, Writer2xhtml And

User's manual for Writer2LaTeX, Writer2BibTeX, Writer2xhtml and Calc2xhtml version 1.4 © 20022014 Henrik Just TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 2 Table of Contents 1 Introduction3 1.1 What is Writer2LaTeX?...............................3 1.2 More about Writer2LaTeX and Writer2BibTeX..................3 1.3 More about Writer2xhtml and Calc2xhtml.....................4 2 Using the export lters5 2.1 Installing of the lters................................5 2.2 Using the lters....................................5 2.3 Using Writer2LaTeX and Writer2BibTeX......................5 2.4 Using Writer2xhtml..................................5 2.5 Using Calc2xhtml...................................6 2.6 Custom conguration.................................6 2.7 Conguration packages................................7 3 Using the command line utility 11 3.1 How to install Writer2LaTeX for command line usage............... 11 3.2 Using the command line utility........................... 11 4 Conguration 15 4.1 Writer2LaTeX conguration............................. 15 4.2 Writer2xhtml and Calc2xhtml conguration.................... 25 4.3 Using LibreOce to create XHTML documents.................. 36 5 Special features for the EPUB export 38 5.1 Meta data....................................... 38 5.2 Hidden hedings.................................... 39 6 The LaTeX package ooomath.sty 40 7 Using Writer2LaTeX from another application 41 7.1 Using Writer2LaTeX from a Java application.................... 41 7.2 Using Writer2LaTeX from a Basic macro...................... 42 7.3 Batch conversion with UNO............................. 43 7.4 Converting from StarMath with a Basic macro................... 45 8 Troubleshooting 46 1 INTRODUCTION Page 3 1 Introduction 1.1 What is Writer2LaTeX? Writer2LaTeX is a utility to convert OpenDocument text and spreadsheet documents1 in particular documents containing formulas into other formats. Actually it is a collection of four converters: l Writer2LaTeX converts OpenDocument text documents to LaTeX 2e, and works together with.. -

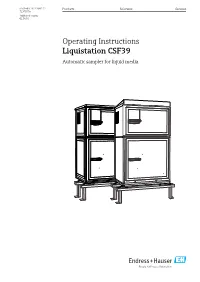

Liquistation CSF39 Automatic Sampler for Liquid Media

BA01407C/07/EN/03.17 Products Solutions Services 71370574 Valid as of version 01.06.04 Operating Instructions Liquistation CSF39 Automatic sampler for liquid media Liquistation CSF39 Table of contents Table of contents 1 About this document ................ 5 8.2 Access to the operating menu via the local display ............................. 46 1.1 Warnings ............................ 5 8.3 Configuration options .................. 47 1.2 Symbols .............................. 5 1.3 Symbols on the device ................... 5 1.4 Documentation ........................ 6 9 Commissioning .................... 50 9.1 Function check ....................... 50 2 Basic safety instructions ............ 7 9.2 Switching on ......................... 50 9.3 Basic setup .......................... 51 2.1 Requirements for personnel ............... 7 9.4 Sampling programs .................... 52 2.2 Designated use ........................ 7 2.3 Occupational safety ..................... 7 2.4 Operational safety ...................... 8 10 Operation ......................... 55 2.5 Product safety ......................... 9 10.1 Display ............................. 55 10.2 General settings ....................... 56 3 Device description ................. 10 10.3 Programming ........................ 73 10.4 Inputs .............................. 95 3.1 Device design ......................... 10 10.5 Outputs ............................ 101 3.2 Equipment architecture ................. 11 10.6 Additional functions .................. 109 3.3 Terminal diagram -

Read Ebook // HTML « NQASJ6LSCMP0

FZUUXENB385J > Book < HTML HTML Filesize: 8.01 MB Reviews Certainly, this is the very best work by any writer. It is loaded with knowledge and wisdom I am just quickly will get a satisfaction of reading through a created publication. (Donavon Okuneva) DISCLAIMER | DMCA UNBLJTVMTK91 « Doc « HTML HTML To read HTML eBook, make sure you refer to the button listed below and save the ebook or have access to additional information which are in conjuction with HTML ebook. Reference Series Books LLC Mrz 2014, 2014. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 246x189x10 mm. Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 75. Chapters: Unicode and HTML, Ruby character, Transclusion, Dynamic HTML, Meta element, Character encodings in HTML, HTML scripting, Image map, HTML element, XHTML, Comparison of layout engines, List of XML and HTML character entity references, HTML attribute, HTML5, HTML5 video, Quirks mode, Html5 in mobile devices, Tag soup, Form, Use of Ogg formats in HTML5, HTML e-mail, Comparison of HTML5 and Flash, MHTML, Span and div, Conditional comment, XHTML+RDFa, File select, CE-HTML, Canvas element, HTML Application, Blink element, Marquee element, Font family, Numeric character reference, Microdata, Alt attribute, FHTML, Meta refresh, Microcontent, The HTML Sourcebook: The Complete Guide to HTML, TeX4ht, HTML decimal character rendering, Table cell, Link relation, Scott Isaacs, Blockquote element, RDDL, JHTML, Layer element, XHTML+SMIL, Validator, HTML color names, Canonical meta tag, HOCR, DVB-HTML, Request Based Distributed Computing, HTML sanitization, Nokogiri. Excerpt: HTML, which stands for HyperText Markup Language, is the predominant markup language for web pages. HTML is the basic building-blocks of webpages. HTML is written in the form of HTML elements consisting of tags, enclosed in angle brackets (like ), within the web page content. -

Wifi Training

Wi-Fi Training - Hands On EMEA application Hands On content 2 • In this presentation we provide a modular training on SPWF04 Wi-Fi module • It can also be used to find answers to common questions on the module • A number of laboratories have been conceived to facilitate the user to get familiar with SPWF04 module key features • Some HW and SW is needed to perform the training • An evaluation environment is offered by ST: • The Nucleo X-Pansion i.e. X-NUCLEO-IDW04A1 • For the evaluation of SPWF features plus other ST components of the Nucleo ecosystem Lab Prerequisites X-NUCLEO-IDW04A1 3 • Hardware • X-NUCLEO-IDW04A1, Wi-Fi expansion board based on SPWF04 module for STM32 Nucleo-64 • NUCLEO-F401RE, NUCLEO-F411RE or NUCLEO-L476RG • Utility software • STSW-WIFI004 FW package • www.st.com/stsw-wifi004 • X-CUBE-WIFI1 SW package • www.st.com/x-cube-wifi1 • Tera Term: terminal emulator • http://en.sourceforge.jp/projects/ttssh2/releases • Notepad++: text editor • https://notepad-plus-plus.org/download • Google Chrome: web browser • https://www.google.it/chrome Hands on chapters 4 • Lab 0 : Module presentation • Lab 7 : Websocket • Lab 1 : HW and SW setup • Lab 8 : HTTP Web Interface • Lab 1.1 : UART Configuration • Lab 8.1 : Web Client Mode • Lab 1.2 : SPI Configuration • Lab 8.2 : Web Server Mode • Lab 1.3 : MicroPython Configuration • Lab 8.2.1 : Web Server Feature • Lab 8.2.1.1 : List, Print a File • Lab 8.2.1.2 : Create, Append and Delete a File in RAM • Lab 2 : Set the SPWF variables • Lab 8.2.1.3 : Create a File in Flash • Lab 8.2.1.3.1