Wes 1981–1982

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Oakland County Aclu Collection

THE OAKLAND COUNTY ACLU COLLECTION Papers, 1970-1984 (Predominantly, 1978-1983) 4 ½ linear feet Accession Number 1170 L.C. Number The papers of the Oakland County American Civil Liberties Union (OCACLU) were placed in the Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs in April of 1984 by James Lafferty and were opened for research in April of 1990. James Lafferty began his work in the area of civil rights when he served as executive secretary for the National Lawyer's Guild in Detroit from 1964-67 and later as legal supervisor for a group of storefront lawyers operations. In his private practice he worked with other attorneys opposing American involvement in Vietnam, counseling young men of draft age. He also ran as a peace candidate in 1966 for Congress in the 17th District against Martha Griffiths. In 1975 Lafferty moved his firm Lafferty & Van Dyke to Birmingham, MI. He became interested in the issue of senior housing (PRIDE) after the initial two ballot defeats. He was elected as a permanent co-chairman to PRIDE and organized its steering committee. Eventually the activities of PRIDE (People Rallying in Defense of Equality) vs. the City of Birmingham lead to the city being sued by the United States government based on racially discriminatory practices. The timing of the PRIDE activities coincided with the formation of the Oakland County ACLU, a process begun in 1970 and finally consummated in December of 1979, based on the recommendation of the Metropolitan Detroit Branch of the ACLU to the Michigan State ACLU Board. The 1979 petition stated as some of the pressing civil liberty issues for the new organization to address as: over 1000 active Oakland County members of the ACLU, the Oakland County jail situation, the policy of giving lie detector tests to rape victims, housing rights of the elderly and retarded in Oakland County, the Oakland County prosecutor's attempts to reinstate the death penalty in Michigan. -

Uniform CPA Examination Unofficial Answers May 1980 to November 1981 American Institute of Certified Public Accountants

University of Mississippi eGrove American Institute of Certified Public Accountants Examinations and Study (AICPA) Historical Collection 1982 Uniform CPA examination unofficial answers May 1980 to November 1981 American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. Board of Examiners Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aicpa_exam Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. Board of Examiners, "Uniform CPA examination unofficial answers May 1980 to November 1981" (1982). Examinations and Study. 120. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aicpa_exam/120 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) Historical Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Examinations and Study by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Uniform CPA Examination May 1980 to November 1981 Unofficial Answers American Institute of AICPA Certified Public Accountants Uniform CPA Examination May 1980 to November 1981 Unofficial Answers Published by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants 1211 Avenue of the Americas New York, N.Y. 10036-8775 Copyright © 1982 American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, Inc. 1211 Avenue of the Americas, New York, N.Y. 10036-8775 1234567890 Ex 898765432 Foreword The texts of the Uniform Certified Public Accountant Examinations, prepared by the Board of Examiners of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants and adopted by the examining boards of all states, territories, and the District of Columbia, are periodically published in book form. Unofficial answers to these examinations appear twice a year as a supplement to the Journal of Accountancy. -

Quantitative Methods (Geography 441) Name: ______SPSS 9: Time Series Dr

Quantitative Methods (Geography 441) Name: ______________________________ SPSS 9: Time Series Dr. Paul Marr Please complete the following exercise using the data below and include a sheet showing your work and results. This sheet MUST be typed using the exercise answer format. Below are the dates and atmospheric CO2 readings from the Mona Loa observatory, Hawaii for the years 1981 - 1985. Please decompose these data into seasonal, trend, and error components using a span of 12. Using these decomposed data, please develop the following graphics: 1. A line graph of the original CO2 concentration over the 5-year period. 2. A line graph of the seasonal component over the 5-year period. 3. A line graph of the CO2 trend over the 5-year period. 4. A bar graph of the error over the 5-year period. Finally, determine if there is a significant trend in CO2 concentrations and predict the trend concentration in Dec 1990. Remember there are 3155760 seconds per year… Double points will be earned if you can add this value and produce a new line graph accurately showing your prediction within the trend series. Date CO2 Date CO2 Date CO2 Date CO2 Date CO2 Jan 1981 339.36 Jan 1982 340.92 Jan 1983 341.64 Jan 1984 344.05 Jan 1985 345.25 Feb 1981 340.51 Feb 1982 341.69 Feb 1983 342.87 Feb 1984 344.77 Feb 1985 346.06 Mar 1981 341.57 Mar 1982 342.85 Mar 1983 343.59 Mar 1984 345.46 Mar 1985 347.66 Apr 1981 342.56 Apr 1982 343.92 Apr 1983 345.25 Apr 1984 346.77 Apr 1985 348.20 May 1981 343.01 May 1982 344.67 May 1983 345.96 May 1984 347.55 May 1985 348.92 Jun -

BORROWING from the PUBLIC $Bil

FEDERAL AND FEDERALLY-ASSISTED BORROWING FROM THE PUBLIC $Bil. $Bil. 40.5 140 140 IS11 Sponsored Agency Obligations V//A Guaranteed Obligations^ 124.4 120 Y//A Off-Budget Deficit 120 WM Budget Deficit1 100 100 80 80 60 60 47.5 40.0 40 40 33.5 24.5 20 17.9 20 0 0 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981e Fiscal Years ±1 Adjusted for other means of financing. 2/ Adjusted for federal and sponsored agency purchases of guaranteed obligations. Ofiice of the Secretary of the Treasury Office of Government Financing e estimate April 28, 1981 16 TREASURY FINANCING REQUIREMENTS January - March 1981 $Bil. $Bil. Uses Sources 60 57Va 60 Redemptions of Special Issues ^1% t| l_| 13/4 Gov't Account Sales 50 Coupon 50 Coupon Maturities | Refundings Savings Bonds 40 40 Va Other Nonmarketables 30 30 Net Market ^ 20 4 Cash Deficit Borrowing " 20 10 10 Decrease in Cash Balance 1V2fr 0 0 u Includes maturing marketable securities of $1/2 billion. Office of the Secretary of the Treasury April 28, 1981-18 Office of Government Financing TREASURY FINANCING REQUIREMENTS April - June 1981 $Bil. $Bil. USES SOURCES 313/4 30 30 Government Account ^Special Issues Investment 20 20 Coupon ±\ a Coupon Maturities t • Refunding 10 Savings 10 Bonds 3/4^1 Net Cash |^11/4 Other Non- T marketables Paydown|^| Cash Surplus^ 4 Increase in Cash Balance^ 0' 0 -V Assumes $15 billion June 30, 1981 cash balance. Office of the Secretary of the Treasury Office of Government Financing April 28,1981-21 NET MARKET BORROWING April - June 1981 Total -2 Cash Management Bills: April Issues 6 April Retirements -16 June Maturities -4 Net Borrowing -14 Other Net Borrowing: 12 Done^ 20 year - 1 month bond 13/4 7 year note 3 2 year note 172 Regular bills Va Total 6Y2 To Be Done SV2 JV Issued or announced through April 24, 1981. -

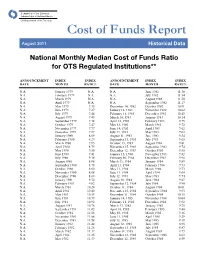

Historical Data

Comptroller of the Currency Administrator of National Banks US Department of the Treasury Cost of Funds Report August 2011 Historical Data National Monthly Median Cost of Funds Ratio for OTS Regulated Institutions** ANNOUNCEMENT INDEX INDEX ANNOUNCEMENT INDEX INDEX DATE MONTH RATE% DATE MONTH RATE% N.A. January 1979 N.A. N.A. June 1982 11.38 N.A. February 1979 N.A. N.A. July 1982 11.54 N.A. March 1979 N.A. N.A. August 1982 11.50 N.A. April 1979 N.A. N.A. September 1982 11.17 N.A. May 1979 7.35 December 14, 1982 October 1982 10.91 N.A. June 1979 7.27 January 12, 1983 November 1982 10.62 N.A. July 1979 7.44 February 11, 1983 December 1982 10.43 N.A. August 1979 7.49 March 14, 1983 January 1983 10.14 N.A. September 1979 7.38 April 12, 1983 February 1983 9.75 N.A. October 1979 7.47 May 13, 1983 March 1983 9.72 N.A. November 1979 7.77 June 14, 1983 April 1983 9.62 N.A. December 1979 7.87 July 13, 1983 May 1983 9.62 N.A. January 1980 8.09 August 11, 1983 June 1983 9.54 N.A. February 1980 8.29 September 13, 1983 July 1983 9.65 N.A. March 1980 7.95 October 13, 1983 August 1983 9.81 N.A. April 1980 8.79 November 15, 1983 September 1983 9.74 N.A. May 1980 9.50 December 12, 1983 October 1983 9.85 N.A. -

Dakota Stage Ltd. Past Productions

Dakota Stage Ltd. Past Productions SEASON ONE 1979-1980 SEPT. 1979 PLAZA SUITE NOV. 1979 TEN LITTLE INDIANS FEB. 1980 SIDE BY SIDE BY SONDHEIM MAY. 1980 BAREFOOT IN THE PARK SEASON TWO 1980-1981 SEPT. 1980 BLITHE SPIRIT OCT. 1980 THE FANTASTICKS DEC. 1980 A CHRISTMAS CAROL FEB. 1981 SAME TIME, NEXT YEAR MAY. 1981 UP ROSE A BURNING MAN SEASON THREE 1981-1982 OCT. 1981 VANITIES DEC. 1981 ANYTHING GOES FEB. 1982 THE GOOD DOCTOR MAY. 1982 THE RUNNER STUMBLES SUMMER 1982 FORT LINCOLN WALKING DRAMA SEASON FOUR 1982-1983 OCT. 1982 6 ROOMS RIVER VIEW DEC. 1982 WAIT UNTIL DARK MARCH. 1983 EQUUS MAY. 1983 ROGERS & HART SUMMER 1983 FORT LINCOLN WALKING DRAMA SEASON FIVE 1983-1984 SEPT. 1983 THE FOUR POSTER NOV. 1983 LUV FEB. 1984 SEE HOW THEY RUN APRIL. 1984 THE SHADOW BOX SUMMER 1984 FORT LINCOLN WALKING DRAMA SEASON SIX 1984-1985 SEPT. 1984 SLEUTH NOV. 1984 LOVERS & OTHER STRANGERS FEB. 1985 JACQUES BREL IS ALIVE AND LIVING IN PARIS MARCH. 1985 FRAGMENTS APRIL. 1985 DIAL M FOR MURDER SUMMER 1985 FORT LINCOLN WALKING DRAMA SEASON SEVEN 1985-1986 OCT. 1985 YOU KNOW I CAN'T HEAR YOU WHEN THE WATER IS RUNNING NOV. 1985 PLAY IT AGAIN SAM FEB. 1986 AGNES OF GOD MARCH. 1986 ROMANTIC COMEDY SUMMER 1986 FORT LINCOLN WALKING DRAMA SEASON EIGHT 1986-1987 SEPT. 1986 DEATHTRAP NOV. 1986 MASS APPEAL FEB. 1987 THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING ERNEST MARCH. 1987 THE PUBLIC EYE APRIL. 1987 THE LECHER & THE ROSE SUMMER 1987 FORT LINCOLN WALKING DRAMA SEASON NINE 1987-1988 OCT. -

Fayette County (Page 1 of 22) Office: Chancery Court

Fayette County (Page 1 of 22) Office: Chancery Court Type of Record Vol Dates Roll Format Notes Minutes S-T May 1925 - Nov 1940 A-3090 35mm Minutes U-V Nov 1940 - May 1956 A-3091 35mm Minutes W-Z May 1956 - May 1976 A-11,625 16mm Minutes 1-3 May 1976 - May 1979 A-11,626 16mm Minutes 4-6 May 1979 - Oct 1980 A-11,627 16mm Minutes 7-9 Oct 1980 - Nov 1981 A-11,628 16mm Minutes 10-12 Nov 1981 - May 1983 A-11,629 16mm Minutes 13-15 May 1983 - May 1985 A-11,630 16mm Minutes 16-18 May 1985 - Jan 1987 A-11,631 16mm Minutes 19-21 Jan 1987 - Sep 1988 A-11,632 16mm Minutes 22-24 Sep 1988 - Feb 1990 A-11,633 16mm Minutes 25-27 Feb 1990 - Jun 1991 A-11,634 16mm Minutes 28-30 Jun 1991 - Jun 1992 A-11,635 16mm Minutes 31-33 Jun 1992 - Apr 1993 A-11,636 16mm Minutes 34-36 Apr 1993 - Jan 1994 A-11,637 16mm Minutes 37-39 Jan 1994 - Oct 1994 A-11,638 16mm Minutes 40-41 Oct 1994 - Jun 1995 A-11,639 16mm Fayette County (Page 2 of 22) Office: Circuit Court Type of Record Vol Dates Roll Format Notes Minutes Jun 1829 - Jun 1832 1 35mm Minutes Dec 1832 - May 1836 1A 35mm Minutes G-H Sep 1842 - Feb 1851 1 35mm Minutes Oct 1858 - Jun 1860 8 35mm Minutes I-J Jun 1859 - Nov 1867 2 35mm Minutes K-L Mar 1868 - Jul 1871 3 35mm Minutes M-N Oct 1871 - Nov 1874 4 35mm Minutes O-P Feb 1875 - Aug 1877 5 35mm Minutes Q-R Oct 1877 - Feb 1880 6 35mm Minutes S-T Jun 1880 - Jul 1882 7 35mm Minutes U-V Oct 1882 - Oct 1885 8 35mm Minutes W-X Feb 1886 - Sep 1891 9 35mm Minutes Y-Z Jan 1892 - Sep 1900 10 35mm Minutes 27-28 Jan 1901 - Apr 1910 A-3092 35mm Minutes 29-30 Jul 1910 - Mar -

Month Calendar 1981 & Holidays 1981

January 1981 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 1 New Year's Day 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 2 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 3 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 4 Martin Luther King Day 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 5 January 1981 Calendar February 1981 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 6 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 7 Lincoln's Birthday Valentine's Day 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 8 Presidents Day and Washington's Birthday 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 9 February 1981 Calendar March 1981 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 10 Mardi Gras Carnival 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 11 Daylight Saving 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 12 St. Patrick's Day 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 13 29 30 31 14 March 1981 Calendar April 1981 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 14 April Fool's Day 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 15 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 16 Good Friday 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 17 Easter Easter Monday 26 27 28 29 30 18 April 1981 Calendar May 1981 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 18 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 19 Cinco de Mayo 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 20 Mother's Day Armed Forces Day 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 21 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 22 Memorial Day 31 23 May 1981 Calendar June 1981 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 23 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 24 Pentecost Pentecost Monday 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 25 Flag Day 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 26 Father's Day 28 29 30 27 June 1981 Calendar July 1981 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 27 Independence Day 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 28 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 -

Recalling Its Resolutions 1979/8 Of9 May 1979, 1980/20 of 30 April 1980

1992/30. Demand for and supply of opiates for medi cal and scientificneeds The Economic and Social Council, Recalling its resolutions 1979/8 of9 May 1979, 1980/20 of 30 April 1980, 1981/8 of 6 May 1981, 1982/12 of 30 April I 982, 1983/3 of 24 May 1983, 1984/21 of 24 May 1984, 1985/16 of 28 May 1985, 1986/9 of 21 May I 986, 1987/31 of 26 May 1987, 1988/10 of 25 May 1988, 1989/15 of 22 May 1989, 1990/31 of 24 May 1990 and 1991/43 of21 June 1991, Emphasizing once again that achieving a balance be tween the licit supply of opiates and the legitimate demand for opiates for medical and scientific purposes constitutes an important aspect of the internationalstrategy and polic: of drug abuse control and that resolving the problem o. excess stocks ofopiate raw materials is an essential step in that direction, Noting the fundamental need for international coopera tion and solidarity in overcoming the problem of excess stocks, which has been imposing heavy financialand other burdens on the traditional supplier countries, Having noted the valuable recommendations made by the InternationalNarcotics Control Board in its special re ports on the demand forand supply of opiates for medical and scientific needs, 78 Having considered the report of the International Nar cotics Control Board for I 991,79 in particular paragraphs 81 to 88 on the demand forand supply of opiates formedi cal and scientificneeds, 1. Urges all Governments to continue to give serious consideration to ways to bring about rapid improvement in solving the problem of excess stocks of opiate raw mate rials held by the traditional supplier countries; 2. -

Thoughts on Professional Sports and the Antitrust Laws: Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum Commission V

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Faculty Articles and Papers School of Law 1983 Thoughts on Professional Sports and the Antitrust Laws: Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum Commission v. National Football League Lewis Kurlantzick University of Connecticut School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_papers Recommended Citation Kurlantzick, Lewis, "Thoughts on Professional Sports and the Antitrust Laws: Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum Commission v. National Football League" (1983). Faculty Articles and Papers. 57. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_papers/57 +(,121/,1( Citation: 15 Conn. L. Rev. 183 1982-1983 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Mon Aug 15 17:02:25 2016 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=0010-6151 CONNECTICUT LAW REVIEW VOLUME 15 WINTER 1983 NUMBER 2 THOUGHTS ON PROFESSIONAL SPORTS AND THE ANTITRUST LAWS: LOS ANGELES MEMORIAL COLISEUM COMMISSION V NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE by Lewis S. Kurlantzick* For the National Football League (NFL), and for other profes- sional sports leagues, the past several years have produced a number of off-field developments that may dramatically affect the structure of league governance. One notable development is the antitrust suit brought by the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum Commission ("the Coliseum") and the Oakland Raiders ("the Raiders") against the NFL after the league attempted to block the team's move to Los Angeles.' At issue in the case is not the financial relationship between players *Professor of Law, University of Connecticut School of Law. -

United Arab Emirates

UNITED ARAB EMIRATES COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Brooks Wrampelmeier 1968-1974 Arabian Peninsula Affairs, Washington, DC William A. Stoltzfus 1972-1976 Ambassador to UAE, Kuwait François M. Dickman 1972-1976 Arabian Peninsula Country Director, Washington, DC Michael E. Sterner 1974-1976 Ambassador, United Arab Emirates François M. Dickman 1976-1979 Ambassador, United Arab Emirates Brooks Wrampelmeier 1977-1980 Deputy Chief of Mission, Abu Dhabi William D. Wolle 1979-1981 Ambassador, United Arab Emirates Brooks Wrampelmeier 1982-1984 Deputy Director/Office Director, Arabian Peninsula Affairs, Washington, DC George Quincey Lumsden 1982-1986 Ambassador, United Arab Emirates David M. Ransom 1983-1985 Deputy Chief of Mission, Abu Dhabi Marjorie Ransom 1983-1985 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Abu Dhabi Andrea Farsakh 1983-1985 Political Officer, Abu Dhabi Michael J. Varga 1985-1987 Consular Officer, Dubai David L. Mack 1986-1989 Ambassador, United Arab Emirates William A. Rugh 1992-1995 Ambassador, United Arab Emirates George Quincey Lumsden 1994-1997 General Manager; Gulf South Asia Gas Project, United Arab Emirates BROOKS WRAMPELMEIER Arabian Peninsula Affairs Washington, DC (1968-1974) 1 Brooks Wrampelmeier was born in Ohio in 1934. He received his bachelor’s degree from Princeton University in 1956. His career has included positions in Beirut, Amman, Jeddah, Lusaka, Abu Dhabi, Kuwait, and Dhahran. Mr. Wrampelmeier was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy in March 2000. Q: I would have thought there would have been a certain conflict from your perspective of Saudi Arabia and Iran, which was our major ally, on the Persian Gulf because the Iranians had claims or eyes, at least, on some of the Gulf states and off shore islands. -

Entering the Quagmire 5

NACLAReport Beyond official rationales, the parallels to ENTERING THE Vietnam are most vividly present on the battle- field. Counterinsurgency, the doctrine devel- QUAGMIRE oped specifically for Vietnam, is today the es- sence of U.S. aid and advice to the Salvadorean junta. Search-and-destroy missions, aerial bombardments, pacification-all the tech- niques of Vietnam are now being used to ter- rorize and kill yet another peasant population. Let me assure you that we are [providing Administration officials are sensitive to the military assistance to El Salvador] with the domestic impact of the analogy. Parallels in lan- greatest prudence and caution and with the guage and actions are discussed at national lessons of the past in mind. El Salvador is security meetings, while official briefings on El not another Vietnam. Our objectives are Salvador are punctuated by assurances that limited: to help the government with its problems of training, equipment, repair and maintenance, mobility and re-supply." Walter J. Stoessel, Under-Secretary for Polit- ical Affairs, testifying before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, March 1981. Comparisons between El Salvador and Viet- nam are heard frequently these days-in Con- gress, at protest rallies, in editorials and at State Department briefings. Some see dangerous par- allels between the two wars, while others dismiss the Vietnam analogy as "an exercise in emo- tion, not analysis."' After careful examination, we think the anal- ogy to Vietnam is appropriate and even com- pelling. It has been injected into the policy de- bate on El Salvador not by "nervous Nellies," as Senator Jesse Helms would have it, nor by loose leftist rhetoric.