Actiniaria, Actiniidae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix to Taxonomic Revision of Leopold and Rudolf Blaschkas' Glass Models of Invertebrates 1888 Catalogue, with Correction

http://www.natsca.org Journal of Natural Science Collections Title: Appendix to Taxonomic revision of Leopold and Rudolf Blaschkas’ Glass Models of Invertebrates 1888 Catalogue, with correction of authorities Author(s): Callaghan, E., Egger, B., Doyle, H., & E. G. Reynaud Source: Callaghan, E., Egger, B., Doyle, H., & E. G. Reynaud. (2020). Appendix to Taxonomic revision of Leopold and Rudolf Blaschkas’ Glass Models of Invertebrates 1888 Catalogue, with correction of authorities. Journal of Natural Science Collections, Volume 7, . URL: http://www.natsca.org/article/2587 NatSCA supports open access publication as part of its mission is to promote and support natural science collections. NatSCA uses the Creative Commons Attribution License (CCAL) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/ for all works we publish. Under CCAL authors retain ownership of the copyright for their article, but authors allow anyone to download, reuse, reprint, modify, distribute, and/or copy articles in NatSCA publications, so long as the original authors and source are cited. TABLE 3 – Callaghan et al. WARD AUTHORITY TAXONOMY ORIGINAL SPECIES NAME REVISED SPECIES NAME REVISED AUTHORITY N° (Ward Catalogue 1888) Coelenterata Anthozoa Alcyonaria 1 Alcyonium digitatum Linnaeus, 1758 2 Alcyonium palmatum Pallas, 1766 3 Alcyonium stellatum Milne-Edwards [?] Sarcophyton stellatum Kükenthal, 1910 4 Anthelia glauca Savigny Lamarck, 1816 5 Corallium rubrum Lamarck Linnaeus, 1758 6 Gorgonia verrucosa Pallas, 1766 [?] Eunicella verrucosa 7 Kophobelemon (Umbellularia) stelliferum -

Fishing and Harvesting of Aquatic

Maine 2015 Wildlife Action Plan Revision Report Date: January 13, 2016 SGCN and Habitat Stressors Level 1 Threat Biological Resource Use Level 2 Threat: Fishing and Harvesting of Aquatic Resources Description: Harvesting aquatic wild animals or plants for commercial, recreation, subsistence, research, or cultural purposes, or for control/persecution reasons; includes accidental mortality/bycatch Species Associated With This Stressor: Total SGCN: 1: 21 2: 48 3: Class Actinopterygii (Ray-finned Fishes) SGCN Category Species: Alosa pseudoharengus (Alewife) 2 Severity: Moderate Severity Actionability: Moderately actionable Notes: Extraction and mortality rates differ widely among Maine runs. Implementing voluntary conservation measures, such as continuous escapement or not fishing the run during the first week, can help ensure sustainable harvests Species: Anguilla rostrata (American Eel) 2 Severity: Moderate Severity Actionability: Moderately actionable Notes: Commercial and Recreational harvest can be effectively regulated or minimized, however timescale of effect on adult spawning populations is long Species: Alosa sapidissima (American Shad) 1 Severity: Moderate Severity Actionability: Moderately actionable Notes: Extraction and mortality rates differ widely among Maine runs. Implementing voluntary conservation measures, such as continuous escapement or not fishing the run during the first week, can help ensure sustainable harvests Species: Thunnus thynnus (Atlantic Bluefin Tuna) 2 Severity: Severe Actionability: Moderately actionable Notes: While fishing mortality in the Western Atlantic has been effectively reduced based on TACs and other measures, fishing mortality continues to be very high in the Eastern Atlantic. The species is also susceptible as bycatch in longlining and other pelagic fishing. Species: Gadus morhua (Atlantic Cod) 1 Severity: Moderate Severity Actionability: Moderately actionable Notes: Historic heavy fishing pressure has drastically reduced Atlantic cod stocks in the Gulf of Maine and Maine waters. -

Download PDF Version

MarLIN Marine Information Network Information on the species and habitats around the coasts and sea of the British Isles Foliose seaweeds and coralline crusts in surge gully entrances MarLIN – Marine Life Information Network Marine Evidence–based Sensitivity Assessment (MarESA) Review Dr Heidi Tillin 2015-11-30 A report from: The Marine Life Information Network, Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. Please note. This MarESA report is a dated version of the online review. Please refer to the website for the most up-to-date version [https://www.marlin.ac.uk/habitats/detail/31]. All terms and the MarESA methodology are outlined on the website (https://www.marlin.ac.uk) This review can be cited as: Tillin, H.M. 2015. Foliose seaweeds and coralline crusts in surge gully entrances. In Tyler-Walters H. and Hiscock K. (eds) Marine Life Information Network: Biology and Sensitivity Key Information Reviews, [on- line]. Plymouth: Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. DOI https://dx.doi.org/10.17031/marlinhab.31.1 The information (TEXT ONLY) provided by the Marine Life Information Network (MarLIN) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share Alike 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. Note that images and other media featured on this page are each governed by their own terms and conditions and they may or may not be available for reuse. Permissions beyond the scope of this license are available here. Based on a work at www.marlin.ac.uk (page left blank) Date: 2015-11-30 Foliose seaweeds and coralline -

MARINE TANK GUIDE About the Marine Tank

HOME EDITION MARINE TANK GUIDE About the Marine Tank With almost 34,000 miles of coastline, Alaska’s intertidal zones, the shore areas exposed and covered by ocean tides, are home to a variety of plants and animals. The Anchorage Museum’s marine tank is home to Alaskan animals which live in the intertidal zone. The plants and animals in the Museum’s marine tank are collected under an Alaska Department of Fish and Game Aquatic Resource Permit during low tide at various beaches in Southcentral and Southeast Alaska. Visitors are asked not to touch the marine animals. Touching is stressful for the animals. A full- time animal care technician maintains the marine tank. Since the tank is not located next to the ocean, ocean water cannot be constantly pumped through it. This means special salt water is mixed at the Museum. The tank is also cleaned regularly. Equipment which keeps the water moving, clean, chilled to 43°F and constantly monitored. Contamination from human hands would impact the cleanliness of the water and potentially hurt the animals. A second tank is home to the Museum’s king crab, named King Louie, and black rockfish, named Sebastian. King crab and black rockfish of Alaska live in deeper waters than the intertidal zone creatures. This guide shares information about some of the Museum’s marine animals. When known, the Dena’ina word for an animal is included, recognizing the thousands of years of stewardship and knowledge of Indigeneous people of the Anchorage area and their language. The Dena’ina & Marine Species The geographically diverse Dena’ina lands span both inland and coastal areas, including Anchorage. -

High Level Environmental Screening Study for Offshore Wind Farm Developments – Marine Habitats and Species Project

High Level Environmental Screening Study for Offshore Wind Farm Developments – Marine Habitats and Species Project AEA Technology, Environment Contract: W/35/00632/00/00 For: The Department of Trade and Industry New & Renewable Energy Programme Report issued 30 August 2002 (Version with minor corrections 16 September 2002) Keith Hiscock, Harvey Tyler-Walters and Hugh Jones Reference: Hiscock, K., Tyler-Walters, H. & Jones, H. 2002. High Level Environmental Screening Study for Offshore Wind Farm Developments – Marine Habitats and Species Project. Report from the Marine Biological Association to The Department of Trade and Industry New & Renewable Energy Programme. (AEA Technology, Environment Contract: W/35/00632/00/00.) Correspondence: Dr. K. Hiscock, The Laboratory, Citadel Hill, Plymouth, PL1 2PB. [email protected] High level environmental screening study for offshore wind farm developments – marine habitats and species ii High level environmental screening study for offshore wind farm developments – marine habitats and species Title: High Level Environmental Screening Study for Offshore Wind Farm Developments – Marine Habitats and Species Project. Contract Report: W/35/00632/00/00. Client: Department of Trade and Industry (New & Renewable Energy Programme) Contract management: AEA Technology, Environment. Date of contract issue: 22/07/2002 Level of report issue: Final Confidentiality: Distribution at discretion of DTI before Consultation report published then no restriction. Distribution: Two copies and electronic file to DTI (Mr S. Payne, Offshore Renewables Planning). One copy to MBA library. Prepared by: Dr. K. Hiscock, Dr. H. Tyler-Walters & Hugh Jones Authorization: Project Director: Dr. Keith Hiscock Date: Signature: MBA Director: Prof. S. Hawkins Date: Signature: This report can be referred to as follows: Hiscock, K., Tyler-Walters, H. -

Fisheries (Southland and Sub-Antarctic Areas Commercial Fishing) Regulations 1986 (SR 1986/220)

Reprint as at 1 October 2017 Fisheries (Southland and Sub-Antarctic Areas Commercial Fishing) Regulations 1986 (SR 1986/220) Paul Reeves, Governor-General Order in Council At Wellington this 2nd day of September 1986 Present: The Right Hon G W R Palmer presiding in Council Pursuant to section 89 of the Fisheries Act 1983, His Excellency the Governor-Gener- al, acting by and with the advice and consent of the Executive Council, hereby makes the following regulations. Contents Page 1 Title, commencement, and application 4 2 Interpretation 4 Part 1 Southland area Total prohibition 3 Total prohibitions 15 Note Changes authorised by subpart 2 of Part 2 of the Legislation Act 2012 have been made in this official reprint. Note 4 at the end of this reprint provides a list of the amendments incorporated. These regulations are administered by the Ministry for Primary Industries. 1 Fisheries (Southland and Sub-Antarctic Areas Reprinted as at Commercial Fishing) Regulations 1986 1 October 2017 Certain fishing methods prohibited 3A Certain fishing methods prohibited in defined areas 16 3AB Set net fishing prohibited in defined area from Slope Point to Sand 18 Hill Point Minimum set net mesh size 3B Minimum set net mesh size 19 3BA Minimum net mesh for queen scallop trawling 20 Set net soak times 3C Set net soak times 20 3D Restrictions on fishing in paua quota management areas 21 3E Labelling of containers for paua taken in any PAU 5 quota 21 management area 3F Marking of blue cod pots and fish holding pots [Revoked] 21 Trawling 4 Trawling prohibited -

Anthopleura and the Phylogeny of Actinioidea (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Actiniaria)

Org Divers Evol (2017) 17:545–564 DOI 10.1007/s13127-017-0326-6 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Anthopleura and the phylogeny of Actinioidea (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Actiniaria) M. Daly1 & L. M. Crowley2 & P. Larson1 & E. Rodríguez2 & E. Heestand Saucier1,3 & D. G. Fautin4 Received: 29 November 2016 /Accepted: 2 March 2017 /Published online: 27 April 2017 # Gesellschaft für Biologische Systematik 2017 Abstract Members of the sea anemone genus Anthopleura by the discovery that acrorhagi and verrucae are are familiar constituents of rocky intertidal communities. pleisiomorphic for the subset of Actinioidea studied. Despite its familiarity and the number of studies that use its members to understand ecological or biological phe- Keywords Anthopleura . Actinioidea . Cnidaria . Verrucae . nomena, the diversity and phylogeny of this group are poor- Acrorhagi . Pseudoacrorhagi . Atomized coding ly understood. Many of the taxonomic and phylogenetic problems stem from problems with the documentation and interpretation of acrorhagi and verrucae, the two features Anthopleura Duchassaing de Fonbressin and Michelotti, 1860 that are used to recognize members of Anthopleura.These (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Actiniaria: Actiniidae) is one of the most anatomical features have a broad distribution within the familiar and well-known genera of sea anemones. Its members superfamily Actinioidea, and their occurrence and exclu- are found in both temperate and tropical rocky intertidal hab- sivity are not clear. We use DNA sequences from the nu- itats and are abundant and species-rich when present (e.g., cleus and mitochondrion and cladistic analysis of verrucae Stephenson 1935; Stephenson and Stephenson 1972; and acrorhagi to test the monophyly of Anthopleura and to England 1992; Pearse and Francis 2000). -

Marine Bivalve Molluscs

Marine Bivalve Molluscs Marine Bivalve Molluscs Second Edition Elizabeth Gosling This edition first published 2015 © 2015 by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd First edition published 2003 © Fishing News Books, a division of Blackwell Publishing Registered Office John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial Offices 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030‐5774, USA For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley‐blackwell. The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author(s) have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. -

Download Complete Work

AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS Birkeland, Charles, P. K. Dayton and N. A. Engstrom, 1982. Papers from the Echinoderm Conference. 11. A stable system of predation on a holothurian by four asteroids and their top predator. Australian Museum Memoir 16: 175–189, ISBN 0-7305-5743-6. [31 December 1982]. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1967.16.1982.365 ISSN 0067-1967 Published by the Australian Museum, Sydney naturenature cultureculture discover discover AustralianAustralian Museum Museum science science is is freely freely accessible accessible online online at at www.australianmuseum.net.au/publications/www.australianmuseum.net.au/publications/ 66 CollegeCollege Street,Street, SydneySydney NSWNSW 2010,2010, AustraliaAustralia THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM, SYDNEY MEMOIR 16 Papers from the Echinoderm Conference THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM SYDNEY, 1978 Edited by FRANCIS W. E. ROWE The Australian Museum, Sydney Published by order of the Trustees of The Australian Museum Sydney, New South Wales, Australia 1982 Manuscripts accepted lelr publication 27 March 1980 ORGANISER FRANCIS W. E. ROWE The Australian Museum, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia CHAIRMEN OF SESSIONS AILSA M. CLARK British Museum (Natural History), London, England. MICHEL J ANGOUX Universite Libre de Bruxelles, Bruxelles, Belgium. PORTER KIER Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., 20560, U.S.A. JOHN LUCAS James Cook University, Townsville, Queensland, Australia. LOISETTE M. MARSH Western Australian Museum, Perth, Western Australia. DAVID NICHOLS Exeter University, Exeter, Devon, England. DAVID L. PAWSON Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.e. 20560, U.S.A. FRANCIS W. E. ROWE The Australian Museum, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. CONTRIBUTIONS BIRKELAND, Charles, University of Guam, U.S.A. 96910. (p. 175). BRUCE, A. -

Predator and Scavenger Aggregation to Discarded By-Catch from Dredge Fisheries: Importance of Damage Level

Journal of Sea Research 51 (2004) 69–76 www.elsevier.com/locate/seares Short Communication Predator and scavenger aggregation to discarded by-catch from dredge fisheries: importance of damage level S.R. Jenkinsa,b,*, C. Mullena, A.R. Branda a Port Erin Marine Laboratory (University of Liverpool), Port Erin, Isle of Man, British Isles, IM9 6JA, UK b Marine Biological Association, Citadel Hill, Plymouth, PL1 2PB, UK Received 23 October 2002; accepted 22 May 2003 Abstract Predator and scavenger aggregation to simulated discards from a scallop dredge fishery was investigated in the north Irish Sea using an in situ underwater video to determine differences in the response to varying levels of discard damage. The rate and magnitude of scavenger and predator aggregation was assessed using three different types of bait, undamaged, lightly damaged and highly damaged individuals of the great scallop Pecten maximus. In each treatment scallops were agitated for 40 minutes in seawater to simulate the dredging process, then subjected to the appropriate damage level before being tethered loosely in front of the video camera. The density of predators and scavengers at undamaged scallops was low and equivalent to recorded periods with no bait. Aggregation of a range of predators and scavengers occurred at damaged bait. During the 24 hour period following baiting there was a trend of increasing magnitude of predator abundance with increasing damage level. However, badly damaged scallops were eaten quickly and lightly damaged scallops attracted a higher overall magnitude of predator abundance over a longer 4 day period. Large scale temporal variability in predator aggregation to simulated discarded biota was examined by comparison of results with those of a previous study, at the same site, 4 years previously. -

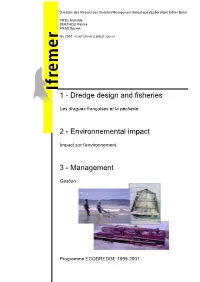

1 - R.Int.Drv/Rh/Lbrest 2001-01

Direction des Ressources Vivantes/Ressources Halieutiques/Laboratoire Côtier Brest PITEL Mathilde BERTHOU Patrick FIFAS Spyros fév 2001 - R.INT.DRV/RH/LBREST 2001-01 1 - Dredge design and fisheries Les dragues françaises et la pêcherie 2 - Environnemental impact Impact sur l’environnement 3 - Management Gestion Programme ECODREDGE 1999-2001 Report 1 – Dredge designs and fisheries These 3 reports have been realised during Ecodredge Program (1999-2001) and contribute to a final ECODREDGE report on international dredges designs and fisheries, environnemetal impact and management. REPORT 1 DREDGE DESIGNS AND FISHERIES ECODREDGE Report 1 – Dredge designs and fisheries Table of contents 1 DREDGE DESIGNS....................................................................................... 5 1.1 Manual dredges for sea-shore fishing................................................................... 7 1.1.1 Recreational fisheries....................................................................................... 7 1.1.2 Professional fisheries........................................................................................ 7 1.2 Flexible Dredges for King scallops (Pecten maximus)......................................... 9 1.3 Flexible and rigid dredges for Warty venus (Venus verrucosa) ....................... 14 1.4 Flexible Dredge for Queen scallops (Chlamys varia, Chlamys opercularia)..... 18 1.5 Rigid Dredges for small bivalves......................................................................... 19 1.6 Flexible Dredge for Mussels -

Marine Invertebrate Field Guide

Marine Invertebrate Field Guide Contents ANEMONES ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 AGGREGATING ANEMONE (ANTHOPLEURA ELEGANTISSIMA) ............................................................................................................................... 2 BROODING ANEMONE (EPIACTIS PROLIFERA) ................................................................................................................................................... 2 CHRISTMAS ANEMONE (URTICINA CRASSICORNIS) ............................................................................................................................................ 3 PLUMOSE ANEMONE (METRIDIUM SENILE) ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 BARNACLES ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 ACORN BARNACLE (BALANUS GLANDULA) ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 HAYSTACK BARNACLE (SEMIBALANUS CARIOSUS) .............................................................................................................................................. 4 CHITONS ...........................................................................................................................................................................................