Daisy Bates First Lady of Little Rock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commonlit | Showdown in Little Rock

Name: Class: Showdown in Little Rock By USHistory.org 2016 This informational text discusses the Little Rock Nine, a group of nine exemplary black students chosen to be the first African Americans to enroll in an all-white high school in the capital of Arkansas, Little Rock. Arkansas was a deeply segregated southern state in 1954 when the Supreme Court ruled that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. The Little Rock Crisis in 1957 details how citizens in favor of segregation tried to prevent the integration of the Little Rock Nine into a white high school. As you read, note the varied responses of Americans to the treatment of the Little Rock Nine. [1] Three years after the Supreme Court declared race-based segregation illegal, a military showdown took place in the capital of Arkansas, Little Rock. On September 3, 1957, nine black students attempted to attend the all-white Central High School. The students were legally enrolled in the school. The National Association for the Advancement of "Robert F. Wagner with Little Rock students NYWTS" by Walter Colored People (NAACP) had attempted to Albertin is in the public domain. register students in previously all-white schools as early as 1955. The Little Rock School Board agreed to gradual integration, with the Superintendent Virgil Blossom submitting a plan in May of 1955 for black students to begin attending white schools in September of 1957. The School Board voted unanimously in favor of this plan, but when the 1957 school year began, the community still raged over integration. When the black students, known as the “Little Rock Nine,” attempted to enter Central High School, segregationists threatened to hold protests and physically block the students from entering the school. -

Exchange with Reporters Prior to Discussions with Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland of Norway May 17, 1994

May 16 / Administration of William J. Clinton, 1994 give our kids a safe and decent and well-edu- We cannot stand chaos and destruction, but cated childhood to put things back together we must not embrace hatred and division. We again. There is no alternative for us if we want have only one choice. to keep this country together and we want, 100 Let me read this to you in closing. It seems years from now, people to celebrate the 140th to me to capture the spirit of Brown and the anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education in spirit of America and what we have to do today, the greatest country the world has ever known, starting with what is in our heart. These are fully diverse, where everybody, all God's chil- lines from Langston Hughes' wonderful poem dren, can live up to the fullest of their God- ``Let America Be America Again'': ``Oh yes, I given potential. say it plain, America never was America to me. And in order to do it, we all have to overcome And yet I swear this oath, America will be.'' a fair measure not only of fear but of resigna- Let that be our oath on this 40th anniversary tion. There are so many of us today, and all celebration. of us in some ways at some times, who just Thank you, and God bless you all. don't believe we can tackle the big things and make a difference. But I tell you, the only thing for us to do to honor those whom we honor NOTE: The President spoke at 8:15 p.m. -

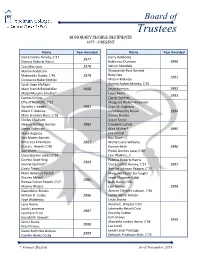

Honorary Degree Recipients 1977 – Present

Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Claire Collins Harvey, C‘37 Harry Belafonte 1977 Patricia Roberts Harris Katherine Dunham 1990 Toni Morrison 1978 Nelson Mandela Marian Anderson Marguerite Ross Barnett Ruby Dee Mattiwilda Dobbs, C‘46 1979 1991 Constance Baker Motley Miriam Makeba Sarah Sage McAlpin Audrey Forbes Manley, C‘55 Mary French Rockefeller 1980 Jesse Norman 1992 Mabel Murphy Smythe* Louis Rawls 1993 Cardiss Collins Oprah Winfrey Effie O’Neal Ellis, C‘33 Margaret Walker Alexander Dorothy I. Height 1981 Oran W. Eagleson Albert E. Manley Carol Moseley Braun 1994 Mary Brookins Ross, C‘28 Donna Shalala Shirley Chisholm Susan Taylor Eleanor Holmes Norton 1982 Elizabeth Catlett James Robinson Alice Walker* 1995 Maya Angelou Elie Wiesel Etta Moten Barnett Rita Dove Anne Cox Chambers 1983 Myrlie Evers-Williams Grace L. Hewell, C‘40 Damon Keith 1996 Sam Nunn Pinkie Gordon Lane, C‘49 Clara Stanton Jones, C‘34 Levi Watkins, Jr. Coretta Scott King Patricia Roberts Harris 1984 Jeanne Spurlock* Claire Collins Harvey, C’37 1997 Cicely Tyson Bernice Johnson Reagan, C‘70 Mary Hatwood Futrell Margaret Taylor Burroughs Charles Merrill Jewel Plummer Cobb 1985 Romae Turner Powell, C‘47 Ruth Davis, C‘66 Maxine Waters Lani Guinier 1998 Gwendolyn Brooks Alexine Clement Jackson, C‘56 William H. Cosby 1986 Jackie Joyner Kersee Faye Wattleton Louis Stokes Lena Horne Aurelia E. Brazeal, C‘65 Jacob Lawrence Johnnetta Betsch Cole 1987 Leontyne Price Dorothy Cotton Earl Graves Donald M. Stewart 1999 Selma Burke Marcelite Jordan Harris, C‘64 1988 Pearl Primus Lee Lorch Dame Ruth Nita Barrow Jewel Limar Prestage 1989 Camille Hanks Cosby Deborah Prothrow-Stith, C‘75 * Former Student As of November 2019 Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Max Cleland Herschelle Sullivan Challenor, C’61 Maxine D. -

Children of Stuggle Learning Guide

Library of Congress LIVE & The Smithsonian Associates Discovery Theater present: Children of Struggle LEARNING GUIDE: ON EXHIBIT AT THE T Program Goals LIBRARY OF CONGRESS: T Read More About It! Brown v. Board of Education, opening May T Teachers Resources 13, 2004, on view through November T Ernest Green, Ruby Bridges, 2004. Contact Susan Mordan, (202) Claudette Colvin 707-9203, for Teacher Institutes and T Upcoming Programs school tours. Program Goals About The Co-Sponsors: Students will learn about the Civil Rights The Library of Congress is the largest Movement through the experiences of three library in the world, with more than 120 young people, Ruby Bridges, Claudette million items on approximately 530 miles of Colvin, and Ernest Green. They will be bookshelves. The collections include more encouraged to find ways in their own lives to than 18 million books, 2.5 million recordings, stand up to inequality. 12 million photographs, 4.5 million maps, and 54 million manuscripts. Founded in 1800, and Education Standards: the oldest federal cultural institution in the LANGUAGE ARTS (National Council of nation, it is the research arm of the United Teachers of English) States Congress and is recognized as the Standard 8 - Students use a variety of national library of the United States. technological and information resources to gather and synthesize information and to Library of Congress LIVE! offers a variety create and communicate knowledge. of program throughout the school year at no charge to educational audiences. Combining THEATER (Consortium of National Arts the vast historical treasures from the Library's Education Associations) collections with music, dance and dialogue. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—HOUSE September 25, 1997

H7838 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð HOUSE September 25, 1997 and $200 billion deficits as far as the willing to go to any length to overturn thing sometime. When is this House eye could see. the election of Congresswoman LORET- going to be ready? When will the lead- With a determination to save the TA SANCHEZ. The committee majority ership of this House be prepared to American dream for the next genera- is in the process of sharing the Immi- clean up the campaign finance mess we tion, the Republican Congress turned gration and Naturalization Service have in this country? the tax-and-spend culture of Washing- records of hundreds of thousands of Or- This House, the people's House, ton upside down and produced a bal- ange County residents with the Califor- should be the loudest voice in the cho- anced budget with tax cuts for the nia Secretary of State. These records rus. We must put a stop to big money American people. Now that the Federal contain personal information on law- special interests flooding the halls of Government's financial house is finally abiding U.S. citizens, many of them our Government. It is time, Madam in order, the big question facing Con- targeted by committee investigators Speaker, for the Republican leadership gress, and the President, by the way, is simply because they have Hispanic sur- to join with us to tell the American what is next? With the average family names or because they reside in certain people that the buck stops here. still paying more in taxes than they do neighborhoods, and that is an outrage. -

Civil Rights2018v2.Key

UNITED STATES HISTORY Civil Rights Era Jackie Robinson Integrates “I Have a Dream” MLB 1945-1975 March on Washington Little Rock Nine 1963 1957 Brown vs Board of Ed. 1954 Civil Rights Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Workers Murdered born 1929 - assassinated1968 1964 Vocabulary • Separate, but Equal - Supreme Court decision that said that separate (but equal) facilities, institutions, and laws for people of different races were were permitted by the Constitution • Segregation - separation of people into groups by race. It may apply to activities such as eating in a restaurant, drinking from a water fountain, riding public transportation, or any public activity • Jim Crow laws - State and local laws passed between 1876 and 1965 that required racial segregation in all public facilities in Southern states that created “legal separate but equal" treatment for African Americans • Integration laws requiring public facilities to be available to people of all races; It’s the opposite of segregation Vocabulary • Civil Disobedience - Refusing to obey certain laws, demands, and commands of a government as a form of non-violent protest - it was used by Gandhi in India and Dr. King in the USA • 13th Amendment - Constitutional amendment that abolished slavery - passed in 1865 • 14th Amendment - Constitutional amendment that guaranteed equal protection of the law to all citizens - passed in 1868 • Lynching - murder by a mob, usually by hanging. Often used by racists to terrorize and intimidate African Americans • Civil Rights Act of 1964 - Law proposed by President Kennedy and eventually made law under President Johnson. The law guaranteed voting rights and fair treatment of African Americans especially in the Southern States People • Mohandus Gandhi (1869-1948) - Used non-violent civil disobedience; Led India to independence and inspired movements for non-violence, civil rights and freedom across the world; his life influenced Dr. -

A Summary of the Contributions of Four Key African American Female Figures of the Civil Rights Movement

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 12-1994 A Summary of the Contributions of Four Key African American Female Figures of the Civil Rights Movement Michelle Margaret Viera Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Viera, Michelle Margaret, "A Summary of the Contributions of Four Key African American Female Figures of the Civil Rights Movement" (1994). Master's Theses. 3834. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3834 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SUMMARY OF THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF FOUR KEY AFRICAN AMERICAN FEMALE FIGURES OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT by Michelle Margaret Viera A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 1994 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My appreciation is extended to several special people; without their support this thesis could not have become a reality. First, I am most grateful to Dr. Henry Davis, chair of my thesis committee, for his encouragement and sus tained interest in my scholarship. Second, I would like to thank the other members of the committee, Dr. Benjamin Wilson and Dr. Bruce Haight, profes sors at Western Michigan University. I am deeply indebted to Alice Lamar, who spent tireless hours editing and re-typing to ensure this project was completed. -

Address at Youth March for Integrated Schools in Washington, D.C., Delivered by Coretta Scott King the Martin Luther King, Jr. P

25 Oct vividly, is the vast outpouring of sympathy and affection that came to me literally 1958 from everywhere-from Negro and white, from Catholic, Protestant and Jew, from the simple, the uneducated, the celebraties and the great. I know that this affection was not for me alone. Indeed it was far too much for any one man to de- serve. It was really for you. It was an expression of the fact that the Montgomery Story had moved the hearts of men everywhere. Through me, the many thou- sands of people who wrote of their admiration, were really writing of their love for you. This is worth remembering. This is worth holding on to as we strive on for Freedom. And finally, as I indicated before, the experience I had in New York gave me time to think. I believe that I have sunk deeper the roots of my convic- tion that (non-violent}resistence is the true path for overcoming in- justice and- for stamping out evil. May God bless you. TAD. MLKP-MBU: Box 93. The Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project Address at Youth March for Integrated Schools in Washington, D.C., Delivered by Coretta Scott King 25 October 1958 New York, N.Y. At the Lincoln Memorial Coretta Scott King delivered these remarks on behalf of her husband to ten thousand people who had marched down Constitution Avenue in support of school integration.’ During the march Harry Belafonte led a small integrated contingent of students to the White House to meet the president. They were met at the gate by a guard who informed them that neither the president nor any of his assistants would be available. -

Principles of Nonviolence: Altering Attitudes and Behaviors of High School Students Regarding Violence and Social Justice

Principles of NonViolence: Altering Attitudes and Behaviors of High School Students Regarding Violence and Social Justice Carolyn Harris-Muchell, PhD, PMHCNS-BC July 21, 2016 Carolyn D. Harris-Muchell West Oakland Health Council, Inc. University of California San Francisco Learning Objectives: 1. The learner will be able to identify two of the six principles at the conclusion of the presentation. 2. The learner will be able to identify 2 areas of their practice in which one or more of the principles would be applicable. No sponsorship provided for this presentation. I am a behavior health specialist with the organization that provides the education intervention. Study Hypothesis w 1. Does an educational experience on civil rights and social justice alter the attitudes of high school students regarding violence and social justice? w 2. Do high school students apply new attitudes into action? w 3. High school students will be transformed to affect change. NonViolence Is the general term for discussing a range of methods for addressing conflict all share the core principle that physical violence is not used against people. Types of NonViolence Strategies Tactical – utilize short to medium term campaigns to achieve a specific goal within society; their aim is reform. Strategic – interested in the structure of social relationships and desire to transform society, a long-term revolutionary strategy. Types of NonViolence Strategies Pragmatic – exponents view conflict as a relationship between antagonists with incompatible interests-goal is to defeat one’s opponent. Ideological - ethical belief in the unity of means and ends, one’s is a partner in the struggle, nonviolence is a way of life. -

OBJ (Application/Pdf)

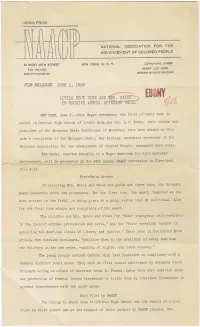

NEWS FROM DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC RELATIONS EXECUTIVE SECRETARY FOR RELEASE: JUNE 5, 1958 LITTLE ROCK NINE AND <RS. BATES'" TO RECEIVE ANNUAL SPINGARN M'EDAT NEV/ YORK, June 5.--Nine Negro teenagers, the first of their race to enroll in Central High School of Little Rock, and Mrs. L.C. Bates, their mentor and president of the Arkansas State Conference of Branches, have been chosen as this year's recipients of the Spingarn Medal, Roy Wilkins, executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, announced here today. The medal, awarded annually to a Negro American for distinguished achievement, will be presented at the 49th annual NAACP convention in Cleveland, Precedents Broken In selecting Mrs. Bates and these six girls and three boys, the Spingarn Award Committee broke two precedents. For the first time, the award, regarded as the most coveted in the field, is being given to a group rather than an individual. Also for the first time minors are recipients of the award. The children and Mrs. Bates are cited for "their courageous self-restraint in the face of extreme provocation and peril," and for "their exemplary conduct in upholding the American ideals of liberty and justice." Their role in the Little Rock crisis, the citation continues, "entitles them to the gratitude of every American who believes in law and order, equality of rights, and human decency." The young people entered Central High last September in compliance with a federal district court order. They were at first denied admittance by Arkansas state troopers acting on orders of Governor Orval E. -

August Activity Packet

Inspirational People FUEL THE PASSION TO CREATE POSITIVE CHANGE WITH BOOKS FROM THESE INSPIRATIONAL PEOPLE! Art © 2019 by Bob Bianchini Whether reading with family or friends, this activity brochure will spark important and thoughtful conversations. This brochure includes: This is Your Time • Discussion Questions It’s Trevor Noah: Born a Crime • Discussion Questions THIS IS YOUR TIME Reader Discussion and Writing Guide Guide your family or group’s discussion about this inspirational letter to today’s young activists from RUBY BRIDGES herself. Art used under license from Shutterstock.com. Photo courtesy of author. Art used under license from Shutterstock.com. Language Advisory: This Is Your Time contains some images of racist language and other offensive epithets. This guide was written by Kimiko Cowley-Pettis. A Brief Overview of the Civil Rights Movement in America THE FIGHT TO END THE SEGREGATION OF PUBLIC FACILITIES The Supreme Court made a ruling in the May 18, Plessy v. Ferguson case that established 1896 the separate but equal doctrine. President Lyndon Johnson signed the July 2, Civil Rights Act of 1964, outlawing 1964 racial discrimination in employment, voting, and the use of public facilities. TIMELINE OF THE FIGHT FOR SCHOOL INTEGRATION The Massachusetts Supreme Court Black and white children went to separate heard arguments about school schools in New Orleans. A judge ordered segregation in Roberts v. the City that four black girls attend two all-white December 4, of Boston. Months later, it declared 1960 schools—McDonogh Elementary School 1849 that school integration would and William Frantz Elementary School. only increase racial prejudice. -

Black Heritage Board Game Section 3

The Black Heritage Trivia Game Section 3 Page 1 Revised August 2015 Section 3 1. Martin Luther King said, "If Blacks could vote there would be no Jim Clarks." Who was Jim Clark? An Alabama sheriff 2. Which Black inventor was instrumental in the creation of trolleys? Granville T. Woods 3. What was the purpose of the National Urban League? To broaden employment opportunities for Black Americans 4. Among the 380 battalion commanders in Vietnam in 1967, how many were African Americans? Two 5. What was Scott Joplin's most famous ragtime composition? The Entertainer 6. What court case upheld the constitutionality of "separate but equal" facilities in transportation, public schools, restaurants and other public facilities? Plessy vs. Ferguson 7. Which Black politician was responsible for opening the House press gallery and the U.S. delegation to the United Nations to Blacks? Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. 8. Who was the first Black police lieutenant of Los Angeles? Thomas Bradley 9. What does the name "ragtime" come from? The name is short for "ragged time" Section 3 Page 1 The Black Heritage Trivia Game Section 3 Page 2 Revised August 2015 10. Actor Sidney Poitier grew up on Cat Island in the Bahamas. How did he lose his West Indian accent? By listening to the radio and repeating everything he heard 11. Who was the first Black astronaut accepted by NASA in 1967? Major Robert H. Lawrence 12. What sport did Berry Gordy participate in before founding Motown Records? Boxing 13. Where did Black inventor Elijah McCoy study mechanical engineering? Scotland 14.