Observations of the First Stygobiont Snail (Hydrobiidae, Fontigens Sp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Systematics of the North and Central American Aquatic Snail Genus Tryonia (Rissooidea: Hydrobiidae)

Systematics of the North and Central American Aquatic Snail Genus Tryonia (Rissooidea: Hydrobiidae) ROBERT HERSF LER m SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO ZOOLOGY • NUMBER 612 SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Folklife Studies Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world of science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the world. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given substantive review. -

Tennessee-Alabama-Georgia (TAG) Cave Teaching and Learning Module

Tennessee-Alabama-Georgia (TAG) Cave Teaching and Learning Module K. Denise Kendall, Ph.D. Matthew L. Niemiller, Ph.D. Annette S. Engel, Ph.D. Funding provided by 1 Dear Educator, We are pleased to present you with a TAG (Tennessee – Alabama – Georgia) cave-themed teaching and learning module. This module aims to engage Kindergarten through 5th grade students in subterranean biology, while fostering awareness and positive attitudes toward cave biodiversity. We have chosen cave fauna for this teaching module because students have a fascination with atypical organisms and environments. Moreover, little attention has been given to subterranean biodiversity in public outreach programs. Many students will likely be intrigued by the unique fauna and composition of subterranean landscapes. Therefore, we hope these lessons enable teachers to introduce students to the unique organisms and habitat below their feet. The module presents students with background information and outlines lessons that aim to reinforce and discover aspects of the content. Lessons in this module focus primarily on habitat formation, biodiversity, evolution, and system flows in subterranean landscapes. We intend for this module to be a guide, and, thus, we have included baseline material and activity plans. Teachers are welcome to use the lessons in any order they wish, use portions of lessons, and may modify the lessons as they please. Furthermore, educators may share these lessons with other school districts and teachers; however, please do not receive monetary gain for lessons in the module. Funding for the TAG Cave module has been graciously provided by the Cave Conservation Foundation, a non-profit 501(c)3 organization dedicated to promoting and facilitating the conservation, management, and knowledge of cave and karst resources. -

Curriculum Vitae (PDF)

CURRICULUM VITAE Steven J. Taylor April 2020 Colorado Springs, Colorado 80903 [email protected] Cell: 217-714-2871 EDUCATION: Ph.D. in Zoology May 1996. Department of Zoology, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois; Dr. J. E. McPherson, Chair. M.S. in Biology August 1987. Department of Biology, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas; Dr. Merrill H. Sweet, Chair. B.A. with Distinction in Biology 1983. Hendrix College, Conway, Arkansas. PROFESSIONAL AFFILIATIONS: • Associate Research Professor, Colorado College (Fall 2017 – April 2020) • Research Associate, Zoology Department, Denver Museum of Nature & Science (January 1, 2018 – December 31, 2020) • Research Affiliate, Illinois Natural History Survey, Prairie Research Institute, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (16 February 2018 – present) • Department of Entomology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (2005 – present) • Department of Animal Biology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (March 2016 – July 2017) • Program in Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation Biology (PEEC), School of Integrative Biology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (December 2011 – July 2017) • Department of Zoology, Southern Illinois University at Carbondale (2005 – July 2017) • Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign (2004 – 2007) PEER REVIEWED PUBLICATIONS: Swanson, D.R., S.W. Heads, S.J. Taylor, and Y. Wang. A new remarkably preserved fossil assassin bug (Insecta: Heteroptera: Reduviidae) from the Eocene Green River Formation of Colorado. Palaeontology or Papers in Palaeontology (Submitted 13 February 2020) Cable, A.B., J.M. O’Keefe, J.L. Deppe, T.C. Hohoff, S.J. Taylor, M.A. Davis. Habitat suitability and connectivity modeling reveal priority areas for Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis) conservation in a complex habitat mosaic. -

Two New Genera of Hydrobiid Snails (Prosobranchia: Rissooidea) from the Northwestern United States

THE VELIGER © CMS, Inc., 1994 The Veliger 37(3):221-243 (July 1, 1994) Two New Genera of Hydrobiid Snails (Prosobranchia: Rissooidea) from the Northwestern United States by ROBERT HERSHLER Department of Invertebrate Zoology (Mollusks), National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 20560, USA TERRENCE J. FREST AND EDWARD J. JOHANNES DEIXIS Consultants, 2517 NE65th Street, Seattle, Washington 98115, USA PETER A. BOWLER Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Irvine, California 92717, USA AND FRED G. THOMPSON Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611, USA Abstract. Based on morphological study of recently collected material, Bythinella hemphilli, distributed within the lower Snake-Columbia River basin, is transferred to a new genus, Pristinicola; and Tay- lorconcha serpenticola, new genus and new species, a federally listed taxon restricted to a short reach of the Middle Snake River in Idaho and previously known by the common name, Bliss Rapids Snail, is described. These genera do not appear closely related either to one another or to other North American Hydrobiidae. INTRODUCTION known. Perhaps the most significant unresolved question pertaining to the local described fauna involves the status Among the large freshwater molluscan fauna of the United of Bythinella hemphilli. Pilsbry's original placement of this States, prosobranch snails of the family Hydrobiidae com- species in Bythinella, which is otherwise known only from pose one of the most diverse groups, totaling about 170 Europe (Banarescu, 1990:342), has long been questioned, described species. Although the state of knowledge of these and two other generic assignments have been offered. -

A Primer to Freshwater Gastropod Identification

Freshwater Mollusk Conservation Society Freshwater Gastropod Identification Workshop “Showing your Shells” A Primer to Freshwater Gastropod Identification Editors Kathryn E. Perez, Stephanie A. Clark and Charles Lydeard University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, Alabama 15-18 March 2004 Acknowledgments We must begin by acknowledging Dr. Jack Burch of the Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan. The vast majority of the information contained within this workbook is directly attributed to his extraordinary contributions in malacology spanning nearly a half century. His exceptional breadth of knowledge of mollusks has enabled him to synthesize and provide priceless volumes of not only freshwater, but terrestrial mollusks, as well. A feat few, if any malacologist could accomplish today. Dr. Burch is also very generous with his time and work. Shell images Shell images unless otherwise noted are drawn primarily from Burch’s forthcoming volume North American Freshwater Snails and are copyright protected (©Society for Experimental & Descriptive Malacology). 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgments...........................................................................................................2 Shell images....................................................................................................................2 Table of Contents............................................................................................................3 General anatomy and terms .............................................................................................4 -

Chapter 21 Freshwater Gastropoda

C. F. Sturm, T. A. Pearce, and A. Valdés. (Eds.) 2006. The Mollusks: A Guide to Their Study, Collection, and Preservation. American Malacological Society. CHAPTER 21 FRESHWATER GASTROPODA ROBERT T. DILLON, Jr. 21.1 INTRODUCTION The largest-bodied freshwater gastropods (adults usually much greater than 2 cm in shell length) be- Gastropods are a common and conspicuous element long to the related families Viviparidae and Ampul- of the freshwater biota throughout most of North lariidae. The former family, including the common America. They are the dominant grazers of algae genera Viviparus and Campeloma, among others, and aquatic plants in many lakes and streams, and is distinguished by bearing live young, sometimes can play a vital role in the processing of detritus and parthenogenically. (Eggs are actually held until decaying organic matter. They are themselves con- they hatch internally, so the term “ovoviviparous” sumed by a host of invertebrate predators, parasites, is more descriptive.) Viviparids have the ability to fish, waterfowl, and other creatures great and small. filter feed, in addition to the more usual grazing An appreciation of freshwater gastropods cannot and scavenging habit. The Ampullariidae, tropical help but lead to an appreciation of freshwater eco- or sub-tropical in distribution, includes Pomacea, systems as a whole (Russell-Hunter 1978, Aldridge which lays its large pink egg mass above the water, 1983, McMahon 1983, Dillon 2000). and Marisa, which attaches large gelatinous egg masses to subsurface vegetation. Ampullariids have 21.2 BIOLOGY AND ECOLOGY famous appetites for aquatic vegetation. The only ampullariid native to the U.S.A. is the Florida apple The most striking attribute of the North Ameri- snail, Pomacea paludosa (Say, 1829), although can freshwater gastropod fauna is its biological other ampullariids have been introduced through diversity. -

American Fisheries Society • JUNE 2013

VOL 38 NO 6 FisheriesAmerican Fisheries Society • www.fisheries.org JUNE 2013 All Things Aquaculture Habitat Connections Hobnobbing Boondoggles? Freshwater Gastropod Status Assessment Effects of Anthropogenic Chemicals 03632415(2013)38(6) Biology and Management of Inland Striped Bass and Hybrid Striped Bass James S. Bulak, Charles C. Coutant, and James A. Rice, editors The book provides a first-ever, comprehensive overview of the biology and management of striped bass and hybrid striped bass in the inland waters of the United States. The book’s 34 chapters are divided into nine major sections: History, Habitat, Growth and Condition, Population and Harvest Evaluation, Stocking Evaluations, Natural Reproduction, Harvest Regulations, Conflicts, and Economics. A concluding chapter discusses challenges and opportunities currently facing these fisheries. This compendium will serve as a single source reference for those who manage or are interested in inland striped bass or hybrid striped bass fisheries. Fishery managers and students will benefit from this up-to-date overview of priority topics and techniques. Serious anglers will benefit from the extensive information on the biology and behavior of these popular sport fishes. 588 pages, index, hardcover List price: $79.00 AFS Member price: $55.00 Item Number: 540.80C Published May 2013 TO ORDER: Online: fisheries.org/ bookstore American Fisheries Society c/o Books International P.O. Box 605 Herndon, VA 20172 Phone: 703-661-1570 Fax: 703-996-1010 Fisheries VOL 38 NO 6 JUNE 2013 Contents COLUMNS President’s Hook 245 Scientific Meetings are Essential If our society considers student participation in our major meetings as a high priority, why are federal and state agen- cies inhibiting attendance by their fisheries professionals at these very same meetings, deeming them non-essential? A colony of the federally threatened Tulotoma attached to the John Boreman—AFS President underside of a small boulder from lower Choccolocco Creek, 262 Talladega County, Alabama. -

Matthew Lance Niemiller

Matthew Lance Niemiller Ph.D. office: (256) 824-3077 Department of Biological Sciences cell: (615) 427-3049 The University of Alabama in Huntsville [email protected] Shelby Center for Science & Technology, Room 302M [email protected] Huntsville, AL 35899 http://www.speleobiology.com/niemiller Google® Scholar: 1,800 citations; h-index: 21; i10-index: 34 ResearchGate: 1,560 citations; h-index: 19; RG Score: 31.69 EDUCATION: 2006–2011 UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE, Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, Knoxville, TN 37996, USA. Doctor of Philosophy, August 2011. Title: Evolution, speciation, and conservation of amblyopsid cavefishes. Advisor: Benjamin M. Fitzpatrick. 2003–2006 MIDDLE TENNESSEE STATE UNIVERSITY, Department of Biology, Murfreesboro, TN 37132, USA. Master of Science, May 2006. Title: Systematics of the Tennessee cave salamander complex (Gyrinophilus palleucus) in Tennessee. Advisor: Brian T. Miller. 2000–2003 MIDDLE TENNESSEE STATE UNIVERSITY, Murfreesboro, TN 37132, USA. Bachelor of Science in Biology, August 2003. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE: 2017–Present Assistant Professor, Department of Biological Sciences, The University of Alabama in Huntsville, Huntsville, AL 35899, USA. 2016–2017 Associate Ecologist, Illinois Natural History Survey, University of Illinois Urbana- Champaign, Champaign, IL 61820, USA. 2013–Present Research Associate, Louisiana State Museum of Natural Science, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA. 2014–2016 Postdoctoral Research Associate, Illinois Natural History Survey, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, IL 61820, USA. Advisor: Steven J. Taylor. 2013–2014 Postdoctoral Scholar, Department of Biology, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40506, USA. Advisor: Catherine Linnen. 2013 Postdoctoral Teaching Scholar, Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520, USA. -

Scholarly Studies Program

OFFICE OF FELLOWSHIPS AND GRANTS SCHOLARLY STUDIES PROGRAM Proposal Cover Sheet Name: S.I. Address & Phone: Principal Investigator: Robert Hershler Department of Invertebrate Zoology National Museum of Natural History NHB E-518 (202) 786-2077 Co-Principal Investigator(s). Hsiu-Ping Liu Biology Department Montclair State University Upper Montclair, NJ 07043 Collaborator(s): None Proposal Title: Phylogeny of Pyrgulopsis Springsnails, a Major Component of North American Aquatic Biodiversity: Implications for Systematics. Biogeography, and Conservation Start Date and Duration of Project: September 1, 1998,. two years Budget Request: Year 1 $28,970 Year 2 $33,536 Total $62,506 P.I.'s Unit Organization Code: 3380 Signatures: Date: Principal Investigator 3/23/98 Co-Principal Investigator 3/23/98 NON-SPECIALIST SUMMARY We request funding to continue and expand a multidisciplinary and collaborative research program on the evolution and biogeography of western American springsnails of the family Hydrobiidae. Although the West provides an outstanding theater for such studies because of its complex and historically dynamic landscape, previous work focused on a single group, fishes. Hydrobiids are an equally suitable study group and also offer distinct advantages over fishes as a consequence of the small size and limited dispersal abilities of these snails. Prior funding from the Scholarly Studies Program enabled us to construct a robust phylogenetic hypothesis for a component of this fauna (genus Tryonia, 21 species) based on mitochondrial DNA sequences -

Recovery Plan for Mobile River Basin Aquatic Ecosystem

Recovery Plan for Mobile River Basin Aquatic Ecosystem U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia MOBILE RIVER BASIN AQUATIC ECOSYSTEM RECOVERY PLAN Prepared by Jackson, Mississippi Field Office U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Mobile River Basin Coalition Planning Committee for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia Approved: Regional Director, U S if~sh and Wildlife Service Date: ___ 2cW MOBILE RIVER BASIN COALITION PLANNING COMMITTEE Chairman Bill Irby Brad McLane Fort James Corp. Alabama Rivers Alliance Daniel Autry John Moore Union Camp Boise Cascade Matt Bowden Rick Oates Baich & Bingham Alabama Pulp & Paper Council Robert Bowker Chris Oberholster U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service The Nature Conservancy Melvin Dixon Brian Peck Pulp & Paper Workers U.S. Army Corps ofEngineers Roger Gerth Robert Reid, Jr. U.S. Army Corps ofEngineers Alabama Audubon Council Marvin Glass, Jr. John Richburg McMillan Blodel Packaging Corp. USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service John Harris USDANatural Resources Conservation Gena Todia Service Wetland Resources Paul Hartfield Ray Vaughn U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Coosa-Tallapoosa Project Jon Hornsby Glenn Waddell Alabama Department of Conservation Baich & Bingham Maurice James Jack Wadsworth U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Farmer Laurie Johnson Alabama River Corporation ii Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions that are believed to be required to recover and/or protect listed species. Plans published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), are sometimes prepared with the assistance ofrecovery teams, contractors, State agencies, and other affected and interested parties. Plans are reviewed by the public and are submitted to additional peer review before they are adopted by the Service. -

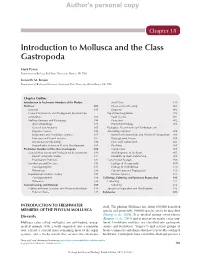

Introduction to Mollusca and the Class Gastropoda

Author's personal copy Chapter 18 Introduction to Mollusca and the Class Gastropoda Mark Pyron Department of Biology, Ball State University, Muncie, IN, USA Kenneth M. Brown Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA Chapter Outline Introduction to Freshwater Members of the Phylum Snail Diets 399 Mollusca 383 Effects of Snail Feeding 401 Diversity 383 Dispersal 402 General Systematics and Phylogenetic Relationships Population Regulation 402 of Mollusca 384 Food Quality 402 Mollusc Anatomy and Physiology 384 Parasitism 402 Shell Morphology 384 Production Ecology 403 General Soft Anatomy 385 Ecological Determinants of Distribution and Digestive System 386 Assemblage Structure 404 Respiratory and Circulatory Systems 387 Watershed Connections and Chemical Composition 404 Excretory and Neural Systems 387 Biogeographic Factors 404 Environmental Physiology 388 Flow and Hydroperiod 405 Reproductive System and Larval Development 388 Predation 405 Freshwater Members of the Class Gastropoda 388 Competition 405 General Systematics and Phylogenetic Relationships 389 Snail Response to Predators 405 Recent Systematic Studies 391 Flexibility in Shell Architecture 408 Evolutionary Pathways 392 Conservation Ecology 408 Distribution and Diversity 392 Ecology of Pleuroceridae 409 Caenogastropods 393 Ecology of Hydrobiidae 410 Pulmonates 396 Conservation and Propagation 410 Reproduction and Life History 397 Invasive Species 411 Caenogastropoda 398 Collecting, Culturing, and Specimen Preparation 412 Pulmonata 398 Collecting 412 General Ecology and Behavior 399 Culturing 413 Habitat and Food Selection and Effects on Producers 399 Specimen Preparation and Identification 413 Habitat Choice 399 References 413 INTRODUCTION TO FRESHWATER shell. The phylum Mollusca has about 100,000 described MEMBERS OF THE PHYLUM MOLLUSCA species and potentially 100,000 species yet to be described (Strong et al., 2008). -

The Invertebrate Cave Fauna of Virginia

Banisteria, Number 42, pages 9-56 © 2013 Virginia Natural History Society The Invertebrate Cave Fauna of Virginia John R. Holsinger Department of Biological Sciences Old Dominion University Norfolk, Virginia 23529 David C. Culver Department of Environmental Science American University 4400 Massachusetts Avenue NW Washington, DC 20016 David A. Hubbard, Jr. Virginia Speleological Survey 40 Woodlake Drive Charlottesville, Virginia 22901 William D. Orndorff Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Division of Natural Heritage Karst Program 8 Radford Street, Suite 102 Christiansburg, Virginia 24073 Christopher S. Hobson Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Division of Natural Heritage 600 East Main Street, 24th Floor Richmond, Virginia 23219 ABSTRACT The obligate cave-dwelling invertebrate fauna of Virginia is reviewed, with the taxonomic status and distribution of each species and subspecies summarized. There are a total of 121 terrestrial (troglobiotic) and 47 aquatic (stygobiotic) species and subspecies, to which can be added 17 stygobiotic species known from Coastal Plain and Piedmont non-cave groundwater habitats, and published elsewhere (Culver et al., 2012a). Richest terrestrial groups are Coleoptera, Collembola, and Diplopoda. The richest aquatic group is Amphipoda. A number of undescribed species are known and the facultative cave-dwelling species are yet to be summarized. Key words: Appalachians, biogeography, biospeleology, caves, springs, stygobionts, subterranean, troglobionts. 10 BANISTERIA NO. 42, 2013 INTRODUCTION METHODS AND MATERIALS The cave fauna of Virginia, most particularly the We assembled all published records, all records obligate cave-dwelling fauna, has been studied and from the Virginia Natural Heritage Program database, described for over 100 years. The first obligate cave- and supplemented this with our own unpublished dwelling species described from a Virginia cave was a records.