Recovery Plan for Mobile River Basin Aquatic Ecosystem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020-2021 Regulations Book of Game, Fish, Furbearers, and Other Wildlife

ALABAMA REGULATIONS 2020-2021 GAME, FISH, FURBEARERS, AND OTHER WILDLIFE REGULATIONS RELATING TO GAME, FISH, FURBEARERS AND OTHER WILDLIFE KAY IVEY Governor CHRISTOPHER M. BLANKENSHIP Commissioner EDWARD F. POOLOS Deputy Commissioner CHUCK SYKES Director FRED R. HARDERS Assistant Director The Department of Conservation and Natural Resources does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, age, sex, national origin, disability, pregnancy, genetic information or veteran status in its hiring or employment practices nor in admission to, access to, or operations of its programs, services or activities. This publication is available in alternative formats upon request. O.E.O. U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 20204 TABLE OF CONTENTS Division of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries Personnel: • Administrative Office .......................................... 1 • Aquatic Education ................................................ 9 • Carbon Hill Fish Hatchery ................................... 8 • Eastaboga Fish Hatchery ...................................... 8 • Federal Game Agents ............................................ 6 • Fisheries Section ................................................... 7 • Fisheries Development ......................................... 9 • Hunter Education .................................................. 5 • Law Enforcement Section ..................................... 2 • Marion Fish Hatchery ........................................... 8 • Mussel Management ............................................ -

Interim Performance Report Endangered Species

INTERIM PERFORMANCE REPORT ENDANGERED SPECIES PROGRAM GRANT NUMBER F17AP01052 WILDLIFE PROJECTS – ALABAMA PROJECT Reproductive Characteristics and Host Fish Determination of Canoe Creek Clubshell, Pleurobema athearni (Gangloff et al. 2006) in Big Canoe Creek drainage (Etowah and St. Clair Counties), Alabama October 1, 2018 - September 30, 2020 ALABAMA DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION AND NATURAL RESOURCES WILDLIFE AND FRESHWATER FISHERIES DIVISION Prepared by: Todd B. Fobian Alabama Division of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries PROJECT Reproductive Characteristics and Host Fish Determination of Canoe Creek Clubshell, Pleurobema athearni (Gangloff et al. 2006) in the Big Canoe Creek drainage (Etowah and St. Clair Counties), Alabama Year 1 Interim Report State: Alabama Introduction Pleurobema athearni (Gangloff et al, 2006), Canoe Creek Clubshell is currently a candidate for federally threatened/endangered status by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS). It is Coosa Basin endemic, with historical records only known from the Big Canoe Creek (BCC) system in Alabama (Gangloff et al. 2006, Williams et al. 2008). Recent surveys completed by ADCNR and USFWS established the species is extant at six localities in the basin, with two in Upper Little Canoe Creek (ULCC), one in Lower Little Canoe Creek (LLCC), and three in BCC proper. (Fobian et al. 2017). As culture methods improve, propagated P. athearni juveniles could soon be available to support reintroduction/augmentation efforts within historical range. Little is known about Pleurobema athearni reproduction, female brooding period, or glochidial hosts. Female P. athearni are presumed short term-brooders and likely gravid from late spring to early summer (Gangloff et al. 2006, Williams et al. 2008). Glochidial hosts are currently unknown although other Mobile River Basin Pleurobema species often utilize Cyprinidae (shiners) to complete metamorphosis (Haag and Warren 1997, 2003, Weaver et al. -

THE NAUTILUS (Quarterly)

americanmalacologists, inc. PUBLISHERS OF DISTINCTIVE BOOKS ON MOLLUSKS THE NAUTILUS (Quarterly) MONOGRAPHS OF MARINE MOLLUSCA STANDARD CATALOG OF SHELLS INDEXES TO THE NAUTILUS {Geographical, vols 1-90; Scientific Names, vols 61-90) REGISTER OF AMERICAN MALACOLOGISTS JANUARY 30, 1984 THE NAUTILUS ISSN 0028-1344 Vol. 98 No. 1 A quarterly devoted to malacology and the interests of conchologists Founded 1889 by Henry A. Pilsbry. Continued by H. Burrington Baker. Editor-in-Chief: R. Tucker Abbott EDITORIAL COMMITTEE CONSULTING EDITORS Dr. William J. Clench Dr. Donald R. Moore Curator Emeritus Division of Marine Geology Museum of Comparative Zoology School of Marine and Atmospheric Science Cambridge, MA 02138 10 Rickenbacker Causeway Miami, FL 33149 Dr. William K. Emerson Department of Living Invertebrates Dr. Joseph Rosewater The American Museum of Natural History Division of Mollusks New York, NY 10024 U.S. National Museum Washington, D.C. 20560 Dr. M. G. Harasewych 363 Crescendo Way Dr. G. Alan Solem Silver Spring, MD 20901 Department of Invertebrates Field Museum of Natural History Dr. Aurele La Rocque Chicago, IL 60605 Department of Geology The Ohio State University Dr. David H. Stansbery Columbus, OH 43210 Museum of Zoology The Ohio State University Dr. James H. McLean Columbus, OH 43210 Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History 900 Exposition Boulevard Dr. Ruth D. Turner Los Angeles, CA 90007 Department of Mollusks Museum of Comparative Zoology Dr. Arthur S. Merrill Cambridge, MA 02138 c/o Department of Mollusks Museum of Comparative Zoology Dr. Gilbert L. Voss Cambridge, MA 02138 Division of Biology School of Marine and Atmospheric Science 10 Rickenbacker Causeway Miami, FL 33149 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF The Nautilus (USPS 374-980) ISSN 0028-1344 Dr. -

Endangered Species

FEATURE: ENDANGERED SPECIES Conservation Status of Imperiled North American Freshwater and Diadromous Fishes ABSTRACT: This is the third compilation of imperiled (i.e., endangered, threatened, vulnerable) plus extinct freshwater and diadromous fishes of North America prepared by the American Fisheries Society’s Endangered Species Committee. Since the last revision in 1989, imperilment of inland fishes has increased substantially. This list includes 700 extant taxa representing 133 genera and 36 families, a 92% increase over the 364 listed in 1989. The increase reflects the addition of distinct populations, previously non-imperiled fishes, and recently described or discovered taxa. Approximately 39% of described fish species of the continent are imperiled. There are 230 vulnerable, 190 threatened, and 280 endangered extant taxa, and 61 taxa presumed extinct or extirpated from nature. Of those that were imperiled in 1989, most (89%) are the same or worse in conservation status; only 6% have improved in status, and 5% were delisted for various reasons. Habitat degradation and nonindigenous species are the main threats to at-risk fishes, many of which are restricted to small ranges. Documenting the diversity and status of rare fishes is a critical step in identifying and implementing appropriate actions necessary for their protection and management. Howard L. Jelks, Frank McCormick, Stephen J. Walsh, Joseph S. Nelson, Noel M. Burkhead, Steven P. Platania, Salvador Contreras-Balderas, Brady A. Porter, Edmundo Díaz-Pardo, Claude B. Renaud, Dean A. Hendrickson, Juan Jacobo Schmitter-Soto, John Lyons, Eric B. Taylor, and Nicholas E. Mandrak, Melvin L. Warren, Jr. Jelks, Walsh, and Burkhead are research McCormick is a biologist with the biologists with the U.S. -

Planorbidae) from New Mexico

FRONT COVER—See Fig. 2B, p. 7. Circular 194 New Mexico Bureau of Mines & Mineral Resources A DIVISION OF NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING & TECHNOLOGY Pecosorbis, a new genus of fresh-water snails (Planorbidae) from New Mexico Dwight W. Taylor 98 Main St., #308, Tiburon, California 94920 SOCORRO 1985 iii Contents ABSTRACT 5 INTRODUCTION 5 MATERIALS AND METHODS 5 DESCRIPTION OF PECOSORBIS 5 PECOSORBIS. NEW GENUS 5 PECOSORBIS KANSASENSIS (Berry) 6 LOCALITIES AND MATERIAL EXAMINED 9 Habitat 12 CLASSIFICATION AND RELATIONSHIPS 12 DESCRIPTION OF MENETUS 14 GENUS MENETUS H. AND A. ADAMS 14 DESCRIPTION OF MENETUS CALLIOGLYPTUS 14 REFERENCES 17 Figures 1—Pecosorbis kansasensis, shell 6 2—Pecosorbis kansasensis, shell removed 7 3—Pecosorbis kansasensis, penial complex 8 4—Pecosorbis kansasensis, reproductive system 8 5—Pecosorbis kansasensis, penial complex 9 6—Pecosorbis kansasensis, ovotestis and seminal vesicle 10 7—Pecosorbis kansasensis, prostate 10 8—Pecosorbis kansasensis, penial complex 10 9—Pecosorbis kansaensis, composite diagram of penial complex 10 10—Pecosorbis kansasensis, distribution map 11 11—Menetus callioglyptus, reproductive system 15 12—Menetus callioglyptus, penial complex 15 13—Menetus callioglyptus, penial complex 16 14—Planorbella trivolvis lenta, reproductive system 16 Tables 1—Comparison of Menetus and Pecosorbis 13 5 Abstract Pecosorbis, new genus of Planorbidae, subfamily Planorbulinae, is established for Biomphalaria kansasensis Berry. The species has previously been known only as a Pliocene fossil, but now is recognized in the Quaternary of the southwest United States, and living in the Pecos Valley of New Mexico. Pecosorbis is unusual because of its restricted distribution and habitat in seasonal rock pools. Most similar to Menetus, it differs in having a preputial organ with an external duct, no spermatheca, and a penial sac that is mostly eversible. -

ECOLOGY of NORTH AMERICAN FRESHWATER FISHES

ECOLOGY of NORTH AMERICAN FRESHWATER FISHES Tables STEPHEN T. ROSS University of California Press Berkeley Los Angeles London © 2013 by The Regents of the University of California ISBN 978-0-520-24945-5 uucp-ross-book-color.indbcp-ross-book-color.indb 1 44/5/13/5/13 88:34:34 AAMM uucp-ross-book-color.indbcp-ross-book-color.indb 2 44/5/13/5/13 88:34:34 AAMM TABLE 1.1 Families Composing 95% of North American Freshwater Fish Species Ranked by the Number of Native Species Number Cumulative Family of species percent Cyprinidae 297 28 Percidae 186 45 Catostomidae 71 51 Poeciliidae 69 58 Ictaluridae 46 62 Goodeidae 45 66 Atherinopsidae 39 70 Salmonidae 38 74 Cyprinodontidae 35 77 Fundulidae 34 80 Centrarchidae 31 83 Cottidae 30 86 Petromyzontidae 21 88 Cichlidae 16 89 Clupeidae 10 90 Eleotridae 10 91 Acipenseridae 8 92 Osmeridae 6 92 Elassomatidae 6 93 Gobiidae 6 93 Amblyopsidae 6 94 Pimelodidae 6 94 Gasterosteidae 5 95 source: Compiled primarily from Mayden (1992), Nelson et al. (2004), and Miller and Norris (2005). uucp-ross-book-color.indbcp-ross-book-color.indb 3 44/5/13/5/13 88:34:34 AAMM TABLE 3.1 Biogeographic Relationships of Species from a Sample of Fishes from the Ouachita River, Arkansas, at the Confl uence with the Little Missouri River (Ross, pers. observ.) Origin/ Pre- Pleistocene Taxa distribution Source Highland Stoneroller, Campostoma spadiceum 2 Mayden 1987a; Blum et al. 2008; Cashner et al. 2010 Blacktail Shiner, Cyprinella venusta 3 Mayden 1987a Steelcolor Shiner, Cyprinella whipplei 1 Mayden 1987a Redfi n Shiner, Lythrurus umbratilis 4 Mayden 1987a Bigeye Shiner, Notropis boops 1 Wiley and Mayden 1985; Mayden 1987a Bullhead Minnow, Pimephales vigilax 4 Mayden 1987a Mountain Madtom, Noturus eleutherus 2a Mayden 1985, 1987a Creole Darter, Etheostoma collettei 2a Mayden 1985 Orangebelly Darter, Etheostoma radiosum 2a Page 1983; Mayden 1985, 1987a Speckled Darter, Etheostoma stigmaeum 3 Page 1983; Simon 1997 Redspot Darter, Etheostoma artesiae 3 Mayden 1985; Piller et al. -

Systematics of the North and Central American Aquatic Snail Genus Tryonia (Rissooidea: Hydrobiidae)

Systematics of the North and Central American Aquatic Snail Genus Tryonia (Rissooidea: Hydrobiidae) ROBERT HERSF LER m SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO ZOOLOGY • NUMBER 612 SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Folklife Studies Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world of science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the world. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given substantive review. -

Part IV: Scoring Criteria for the Index of Biotic Integrity to Monitor

Part IV: Scoring Criteria for the Index of Biotic Integrity to Monitor Fish Communities in Wadeable Streams in the Coosa and Tennessee Drainage Basins of the Ridge and Valley Ecoregion of Georgia Georgia Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Resources Division Fisheries Management Section 2020 Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………… ……... Pg. 1 Map of Ridge and Valley Ecoregion………………………………..……............... Pg. 3 Table 1. State Listed Fish in the Ridge and Valley Ecoregion……………………. Pg. 4 Table 2. IBI Metrics and Scoring Criteria………………………………………….Pg. 5 References………………………………………………….. ………………………Pg. 7 Appendix 1…………………………………………………………………. ………Pg. 8 Coosa Basin Group (ACT) MSR Graphs..………………………………….Pg. 9 Tennessee Basin Group (TEN) MSR Graphs……………………………….Pg. 17 Ridge and Valley Ecoregion Fish List………………………………………Pg. 25 i Introduction The Ridge and Valley ecoregion is one of the six Level III ecoregions found in Georgia (Part 1, Figure 1). It is drained by two major river basins, the Coosa and the Tennessee, in the northwestern corner of Georgia. The Ridge and Valley ecoregion covers nearly 3,000 square miles (United States Census Bureau 2000) and includes all or portions of 10 counties (Figure 1), bordering the Piedmont ecoregion to the south and the Blue Ridge ecoregion to the east. A small portion of the Southwestern Appalachians ecoregion is located in the upper northwestern corner of the Ridge and Valley ecoregion. The biotic index developed by the GAWRD is based on Level III ecoregion delineations (Griffith et al. 2001). The metrics and scoring criteria adapted to the Ridge and Valley ecoregion were developed from biomonitoring samples collected in the two major river basins that drain the Ridge and Valley ecoregion, the Coosa (ACT) and the Tennessee (TEN). -

December 2017

Ellipsaria Vol. 19 - No. 4 December 2017 Newsletter of the Freshwater Mollusk Conservation Society Volume 19 – Number 4 December 2017 Cover Story . 1 Society News . 4 Announcements . 7 Regional Meetings . 8 March 12 – 15, 2018 Upcoming Radisson Hotel and Conference Center, La Crosse, Wisconsin Meetings . 9 How do you know if your mussels are healthy? Do your sickly snails have flukes or some other problem? Contributed Why did the mussels die in your local stream? The 2018 FMCS Workshop will focus on freshwater mollusk Articles . 10 health assessment, characterization of disease risk, and strategies for responding to mollusk die-off events. FMCS Officers . 19 It will present a basic understanding of aquatic disease organisms, health assessment and disease diagnostic tools, and pathways of disease transmission. Nearly 20 Committee Chairs individuals will be presenting talks and/or facilitating small group sessions during this Workshop. This and Co-chairs . 20 Workshop team includes freshwater malacologists and experts in animal health and disease from: the School Parting Shot . 21 of Veterinary Medicine, University of Minnesota; School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Wisconsin; School 1 Ellipsaria Vol. 19 - No. 4 December 2017 of Fisheries, Aquaculture, and Aquatic Sciences, Auburn University; the US Geological Survey Wildlife Disease Center; and the US Fish and Wildlife Service Fish Health Center. The opening session of this three-day Workshop will include a review of freshwater mollusk declines, the current state of knowledge on freshwater mollusk health and disease, and a crash course in disease organisms. The afternoon session that day will include small panel presentations on health assessment tools, mollusk die-offs and kills, and risk characterization of disease organisms to freshwater mollusks. -

Geological Survey of Alabama Calibration of The

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF ALABAMA Berry H. (Nick) Tew, Jr. State Geologist WATER INVESTIGATIONS PROGRAM CALIBRATION OF THE INDEX OF BIOTIC INTEGRITY FOR THE SOUTHERN PLAINS ICHTHYOREGION IN ALABAMA OPEN-FILE REPORT 0908 by Patrick E. O'Neil and Thomas E. Shepard Prepared in cooperation with the Alabama Department of Environmental Management and the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Tuscaloosa, Alabama 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................ 1 Introduction.......................................................... 1 Acknowledgments .................................................... 6 Objectives........................................................... 7 Study area .......................................................... 7 Southern Plains ichthyoregion ...................................... 7 Methods ............................................................ 8 IBI sample collection ............................................. 8 Habitat measures............................................... 10 Habitat metrics ........................................... 12 The human disturbance gradient ................................... 15 IBI metrics and scoring criteria..................................... 19 Designation of guilds....................................... 20 Results and discussion................................................ 22 Sampling sites and collection results . 22 Selection and scoring of Southern Plains IBI metrics . 41 1. Number of native species ................................ -

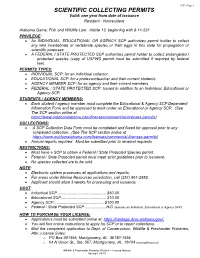

SCIENTIFIC COLLECTING PERMITS Valid: One Year from Date of Issuance Resident - Nonresident

SCP – Page 1 SCIENTIFIC COLLECTING PERMITS Valid: one year from date of issuance Resident - Nonresident Alabama Game, Fish and Wildlife Law; Article 12; beginning with 9-11-231 PRIVILEGE: • An INDIVIDUAL, EDUCATIONAL OR AGENCY SCP authorizes permit holder to collect any wild invertebrate or vertebrate species or their eggs in this state for propagation or scientific purposes. • A FEDERAL / STATE PROTECTED SCP authorizes permit holder to collect endangered / protected species (copy of USFWS permit must be submitted if required by federal law). PERMITS TYPES: • INDIVIDUAL SCP: for an individual collector. • EDUCATIONAL SCP: for a professor/teacher and their current students. • AGENCY MEMBER SCP: for an agency and their current members. • FEDERAL / STATE PROTECTED SCP: Issued in addition to an Individual, Educational or Agency SCP. STUDENTS / AGENCY MEMBERS: • Each student / agency member must complete the Educational & Agency SCP Dependent Information Form and be approved to work under an Educational or Agency SCP. (See The SCP section online at https://www.outdooralabama.com/licenses/commercial-licenses-permits) COLLECTIONS: • A SCP Collection Data Form must be completed and faxed for approval prior to any scheduled collection. (See The SCP section online at https://www.outdooralabama.com/licenses/commercial-licenses-permits) • Annual reports required. Must be submitted prior to renewal requests. RESTRICTIONS: • Must have a SCP to obtain a Federal / State Protected Species permit. • Federal / State Protected permit must meet strict guidelines prior to issuance. • No species collected are to be sold. NOTE: • Electronic system processes all applications and reports. • For areas under Marine Resources jurisdiction, call (251) 861-2882. • Applicant should allow 3 weeks for processing and issuance. -

Federal Register/Vol. 81, No. 194

Federal Register / Vol. 81, No. 194 / Thursday, October 6, 2016 / Rules and Regulations 69425 the Interior’s manual at 512 DM 2, we References Cited Regulation Promulgation readily acknowledge our responsibility Accordingly, we amend part 17, to communicate meaningfully with A complete list of references cited in this rulemaking is available on the subchapter B of chapter I, title 50 of the recognized Federal Tribes on a Code of Federal Regulations, as follows: government-to-government basis. In Internet at http://www.regulations.gov accordance with Secretarial Order 3206 and upon request from the Panama City PART 17—ENDANGERED AND of June 5, 1997 (American Indian Tribal Ecological Services Field Office (see FOR THREATENED WILDLIFE AND PLANTS Rights, Federal-Tribal Trust FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT). ■ 1. The authority citation for part 17 Responsibilities, and the Endangered Authors Species Act), we readily acknowledge continues to read as follows: our responsibilities to work directly The primary authors of this final rule Authority: 16 U.S.C. 1361–1407; 1531– with tribes in developing programs for are the staff members of the Panama 1544; 4201–4245; unless otherwise noted. healthy ecosystems, to acknowledge that City Ecological Services Field Office. ■ 2. Amend § 17.11(h) by adding an tribal lands are not subject to the same List of Subjects in 50 CFR Part 17 entry for ‘‘Moccasinshell, Suwannee’’ to controls as Federal public lands, to the List of Endangered and Threatened remain sensitive to Indian culture, and Endangered and threatened species, Wildlife in alphabetical order under to make information available to tribes. Exports, Imports, Reporting and CLAMS to read as set forth below: The Suwannee moccasinshell is not recordkeeping requirements, § 17.11 Endangered and threatened known to occur within any tribal lands Transportation.