The Influence of R2p on Non-Forceful Responses to Atrocity Crimes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crossing the Line Between News and the Business of News: Exploring Journalists' Use of Twitter Jukes, Stephen

www.ssoar.info Crossing the line between news and the business of news: exploring journalists' use of Twitter Jukes, Stephen Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Jukes, S. (2019). Crossing the line between news and the business of news: exploring journalists' use of Twitter. Media and Communication, 7(1), 248-258. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v7i1.1772 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY Lizenz (Namensnennung) zur This document is made available under a CC BY Licence Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden (Attribution). For more Information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de Media and Communication (ISSN: 2183–2439) 2019, Volume 7, Issue 1, Pages 248–258 DOI: 10.17645/mac.v7i1.1772 Article Crossing the Line between News and the Business of News: Exploring Journalists’ Use of Twitter Stephen Jukes Faculty of Media and Communication, Bournemouth University, Poole, BH12 5BB, UK; E-Mail: [email protected] Submitted: 7 September 2018 | Accepted: 4 January 2018 | Published: 21 March 2019 Abstract Anglo-American journalism has typically drawn a firm dividing line between those who report the news and those who run the business of news. This boundary, often referred to in the West as a ‘Chinese Wall’, is designed to uphold the inde- pendence of journalists from commercial interests or the whims of news proprietors. But does this separation still exist in today’s age of social media and at a time when news revenues are under unprecedented pressure? This article focuses on Twitter, now a widely used tool in the newsroom, analysing the Twitter output of 10 UK political correspondents during the busy party conference season. -

Annex to the BBC Annual Report and Accounts 2016/17

Annual Report and Accounts 2016/17 Annex to the BBC Annual Report and Accounts 2016/17 Annex to the BBC Annual Report and Accounts 2016/17 Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport by command of Her Majesty © BBC Copyright 2017 The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as BBC copyright and the document title specified. Photographs are used ©BBC or used under the terms of the PACT agreement except where otherwise identified. Permission from copyright holders must be sought before any photographs are reproduced. You can download this publication from bbc.co.uk/annualreport BBC Pay Disclosures July 2017 Report from the BBC Remuneration Committee of people paid more than £150,000 of licence fee revenue in the financial year 2016/17 1 Senior Executives Since 2009, we have disclosed salaries, expenses, gifts and hospitality for all senior managers in the BBC, who have a full time equivalent salary of £150,000 or more or who sit on a major divisional board. Under the terms of our new Charter, we are now required to publish an annual report for each financial year from the Remuneration Committee with the names of all senior executives of the BBC paid more than £150,000 from licence fee revenue in a financial year. These are set out in this document in bands of £50,000. -

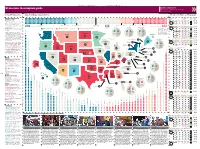

US Election: the Complete Guide Follow the Race

26 * The Guardian | Tuesday 6 November 2012 The Guardian | Tuesday 6 November 2012 * 27 Big news, small screen US election: the complete guide Live election results and commentary m.guardian.co.uk ≥ Follow the race The battleground states Work out who is winning Poll closes State How they voted Electoral college Election night 2012 on (GMT) 1988-2008 Votes Tally guardian.co.uk Bush Sr | Bush Sr | Dole | Live blog Wins, losses, too-close-to-calls, Indiana Bush | Bush | Obama 11 hanging chads — follow all the rollercoaster Bush Sr | Clinton | Clinton | action of election night as the results come Kentucky Bush | Bush | McCain 8 in with Richard Adams’s unrivalled live blog, 154 solid Democrat 29 likely to vote Democrat 18 leaning towards the Democrat 270 electoral college 11 leaning towards the Republicans 44 likely to vote Republican 127 solid Republican featuring dispatches from Guardian reporters votes needed to win Barack Obama and Democrats Mitt Romney and Republicans Bush Sr | Bush Sr | Clinton | and analysts across the US. 201 155 Wisconsin Michigan New Hampshire 182 Florida Bush | Bush | Obama Undecided 29 Live picture blog Our picture editors show Barack Obama & Democrats Mitt Romney & Republicans Undecided 1 Number of electoral college votes per state *Maine and Nebraska are the Bush Sr | Clinton | Dole | you the pick of the election images from both *Maine and Nebraska Georgia Bush | Bush | McCain 16 (+14) onlyare two the statestwo only that states allocate campaigns 55 theirthat electoral allocates college its votes Bush Sr | Clinton | Clinton | N Hampshire Bush | Kerry | Obama 4 Real time results Watch our amazing by electoralcongressional college district. -

Spring 2020 Bulletin 127

Championing Excellence and Diversity in Broadcasting Spring 2020 Bulletin 127 BBC SEARCHES FOR NEW DG VLV’s 37th ANNUAL AS VLV ANALYSIS SHOWS SPRING CONFERENCE 30% BUDGET CUT SINCE 2010 Thursday 30 April 2020 The BBC is looking for a new director-general to replace Tony Hall amid mounting political pressure from the government over the licence fee. The BBC is also bracing itself for negative publicity as it gears up to restrict the number of over 75 households that can receive free TV licences. The unprecedented strain on the corporation is laid bare in an analysis by the VLV that shows the BBC’s budget for UK services has been slashed by 30% in real terms over the past decade. VLV believes that the gathering threats to the BBC Patrick Barwise and Peter York, the authors of a could lead to its demise in its current form because they forthcoming book about the BBC, are to speak at the point to a full review of whether the BBC should remain VLV Spring Conference on 30 April. They will be a universal service. What happens will depend on the addressing the multiple threats facing the BBC, a theme government, despite there having been no commitment likely to dominate the conference. Their book, The War to review the BBC’s funding model in the 2019 Against the BBC, will be published in the summer. The Conservative manifesto. conference will include the VLV Awards for Excellence in Broadcasting 2019 – for more details about the This crisis has hit the BBC when it is already having to awards, see page 8. -

Right Address Brochure

After Dinner Speakers, Conference Hosts, Presenters & Entertainers stablished in 1988 The Right Address is an experienced, professional and friendly speaker and entertainment consultancy. EUnderstanding the challenges that can arise when you are organising a conference, dinner, or any business event, has been the key to our success over the years. What can you expect from The Right Address? We offer you the best in after dinner and business speakers, If you would like to browse through more ideas before cabaret and musical entertainment. From well known names speaking to one of our consultants you can do so by visiting to those you may not have heard of, we pride ourselves our website www.therightaddress.co.uk in getting the perfect speaker for your event. The right speaker, or presenter, can turn a routine annual dinner The website enables you to search for a speaker by name, into a memorable occasion, or your awards evening into or category and provides more details on each speaker, a glamorous high profile event, which your guests will be performer or comedian listed. speaking about for weeks to come. Whilst browsing the site you can create your very own You can expect from The Right Address the top business wish list as you go. This can either be saved to refer to and keynote speakers, from captains of industry, at a later date or sent to us to request more information politicians, experts in the economy, technology, on your chosen selection. Alternatively there is an enquiry banking and the environment, to the most vibrant up form to complete and send to us if you have additional and coming entrepreneurs. -

Misses the Point

BUSINESS WITH PERSONALITY CHELSEA’S BLUES A LEAN, GREEN MACHINE MAGUIRE HEADS THE FIRM GIVING CLASSIC UNITED TO WIN AT CARS A CLEAN FUTURE P24 THE BRIDGE P26 TUESDAY 18 FEBRUARY 2020 ISSUE 3,558 CITYAM.COM FREE A cyclist battles the snow in Wuhan — the EU ‘misses coronavirus’ epicentre the point’ of GLOBAL Leave vote CATHERINE NEILAN @CatNeilan BRITAIN's refusal to align itself with EU regulations is not “some clever tactical TRADE position” but the entire object of Brexit, Boris Johnson’s chief negotiator said last night. In a stark warning that the UK would not capitulate to demands over the so-called level-playing field, which includes rules around competition, the environment FEELS and tax, David Frost stressed that the EU “fails to see the point of what we are doing” in breaking away from the bloc. “We bring to the negotiations not some clever tactical positioning but the fundamentals of what it means to be an independent THE CHILL country,” he said in a lecture CORONAVIRUS EXPECTED TO MAKE GRIM to the Universite Libre de Bruxelles, just a fortnight WORLD TRADE FIGURES WORSE IN 2020 before talks are due to start. “It is central to our vision EDWARD THICKNESSE which the WTO expects to have an impact areas such as container shipping and GDP growth predicted that G20 economies that we must have the ability @edthicknesse across every element of global goods trade. agricultural raw materials, which fell to will grow a collective 2.4 per cent in 2020, a to set laws that suit us – to The WTO said: “Every component of the 94.8 and 90.9 respectively. -

A List of the 238 Most Respected Journalists, As Nominated by Journalists in the 2018 Journalists at Work Survey

A list of the 238 most respected journalists, as nominated by journalists in the 2018 Journalists at Work survey Fran Abrams BBC Radio 4 & The Guardian Seth Abramson Freelance investigative journalist Kate Adie BBC Katya Adler BBC Europe Jonathan Ali BBC Christiane Amanpour CNN Lynn Ashwell Formerly Bolton News Mary-Ann Astle Stoke on Trent Live Michael Atherton The Times and Sky Sports Sue Austin Shropshire Star Caroline Barber CN Group Lionel Barber Financial Times Emma Barnett BBC Radio 5 Live Francis Beckett Author & journalist Vanessa Beeley Blogger Jessica Bennett New York Times Heidi Blake BuzzFeed David Blevins Sky News Ian Bolton Sky Sports News Susie Boniface Daily Mirror Samantha Booth Islington Tribune Jeremy Bowen BBC Tom Bradby ITV Peter Bradshaw The Guardian Suzanne Breen Belfast Telegraph Billy Briggs Freelance Tom Bristow Archant investigations unit Samuel Brittan Financial Times David Brown The Times Fiona Bruce BBC Michael Buchanan BBC Jason Burt Daily Telegraph & Sunday Telegraph Carole Cadwalladr The Observer & The Guardian Andy Cairns Sky Sports News Michael Calvin Author Duncan Campbell Investigative journalist and author Severin Carrell The Guardian Reeta Chakrabarti BBC Aditya Chakrabortty The Guardian Jeremy Clarkson Broadcaster, The Times & Sunday Times Matthew Clemenson Ilford Recorder and Romford Recorder Michelle Clifford Sky News Patrick Cockburn The Independent Nick Cohen Columnist Teilo Colley Press Association David Conn The Guardian Richard Conway BBC Rob Cotterill The Sentinel, Staffordshire Alex Crawford -

BBC Annual Report and Accounts 2017/18

Annual Report and Accounts 2017/18 BBC Annual Report and Accounts 2017/18 Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport by Command of Her Majesty © BBC Copyright 2018 The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as BBC copyright and the document title specified. Photographs are used ©BBC or used under the terms of the PACT agreement except where otherwise identified. Permission from copyright holders must be sought before any photographs are reproduced. You can download this publication from bbc.co.uk/annualreport Designed by Emperor emperor.works Prepared pursuant to the BBC Royal Charter 2016 (Article 37) ABOUT THE BBC Contents Nations’ data packs p.150 Performance and market context p.02 p.59 p.168 About the BBC Detailed financial The year at a glance, award-winning statements content and how we’re structured p.08 Forewords from the Chairman and Director-General Performance against public commitments p.240 p.125 Equality Information Report Governance p.88 p.66 Finance and Delivering our creative remit operations How we’ve met the requirements of our public purposes p.18 About the BBC Governance Financial statements 02 The year at a glance 90 BBC Board 169 Certificate and Report of the Comptroller 92 Governance Report and Auditor General Strategic report 93 Remuneration -

BBC Group Annual Report and Accounts 2019/20

BBC Group Annual Report and Accounts 2019/20 BBC Group Annual Report and Accounts 2019/20 Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport by Command of Her Majesty © BBC Copyright 2020 The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as BBC copyright and the document title specified. Photographs are used ©BBC or used under the terms of the PACT agreement except where otherwise identified. Permission from copyright holders must be sought before any photographs are reproduced. You can download this publication from bbc.co.uk/annualreport Designed by Emperor emperor.works Prepared pursuant to the BBC Royal Charter 2016 (Article 37) Contents Contents About the BBC Governance report Financial statements 02 Informing, educating and 70 BBC Board 159 Certificate and Report entertaining the UK in 2019/20 71 Executive Committee of the Comptroller and 04 Coronavirus: informing, 71 Next Generation Committee Auditor General educating, and entertaining in 72 Corporate Compliance Report 171 Consolidated income statement lockdown 73 Remuneration Report 171 Consolidated statement of Strategic report 81 Pay disclosures comprehensive income/(loss) 89 NAO opinion on pay 172 Consolidated balance sheet p 06 Statement from the Chairman 173 Consolidated statement of 08 Director-General’s statement -

Britain at the Crossroads’, 29 March 2018

THE BBC AND BREXIT SURVEY OF A DAY OF SPECIAL RADIO 4 PROGRAMMES: ‘BRITAIN AT THE CROSSROADS’, 29 MARCH 2018 Table of Contents Introduction: Britain at the Crossroads ......................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary: Britain at the Crossroads .......................................................................................... 4 PART 1: GLOBAL STATISTICS ............................................................... 6 1.1 Airtime ......................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Speakers ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 PART 2: INDIVIDUAL PROGRAMMES ...............................................12 2.1 Today ........................................................................................................................................................ 12 2.2 The Long View ......................................................................................................................................... 14 2.3 Dead Ringers ........................................................................................................................................... 16 2.4 The Channel ............................................................................................................................................. -

Kent Academic Repository Full Text Document (Pdf)

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Luckhurst, Tim and Cocking, Ben and Reeves, Ian and Bailey, Rob (2019) Assessing the Delivery of BBC Radio 5 Live's Public Service Commitments. Abramis Academic Publishing, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, UK, 44 pp. ISBN 978-1-84549-558-9. (In press) DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/71586/ Document Version Publisher pdf Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Assessing the Delivery of BBC Radio 5 Live’s Public Service Commitments By Tim Luckhurst, Ben Cocking, Ian Reeves and Rob Bailey, Centre for Journalism, University of Kent Published 2019 by Abramis academic publishing www.abramis.co.uk ISBN 978 1 84549 ** * ©Tim Luckhurst, Ben Cocking, Ian Reeves & Rob Bailey 2019 All rights reserved his publication is copyright. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Thursday Volume 608 14 April 2016 No. 143 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Thursday 14 April 2016 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2016 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 489 14 APRIL 2016 490 “the courts and the CPS were not comfortable with live links House of Commons even though the video technology was available.” What more can be done to spread consistency in its Thursday 14 April 2016 uptake? The Solicitor General: My hon. Friend is quite right The House met at half-past Nine o’clock to highlight that important report. In places such as Kent, best practice is clearly being demonstrated. With regard to national training, which is happening now, we PRAYERS will see more and more use of live links from victims’ homes and other safe places to avoid the terrible ordeal [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] in many cases of victims having to come to court to give evidence in the courtroom. Colleen Fletcher (Coventry North East) (Lab): Providing Oral Answers to Questions effective and compassionate support for victims and survivors of sexual violence is pivotal to ensuring that more of these heinous crimes are reported in the first place, and, ultimately, that more offenders are brought ATTORNEY GENERAL to justice. Will the Minister tell me how the Government intend to improve victim and witness care within the The Attorney General was asked— criminal justice system? Rape and Serious Sexual Offences The Solicitor General: The hon.