Facultynewsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

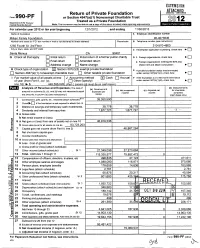

990-PF I Return of Private Foundation

EXTENSION Return of Private Foundation WNS 952 Form 990-PF I or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation 2012 Department of the Treasury Internal Reventie Service Note . The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting req For calendar year 2012 or tax year beginning 12/1/2012 , and ending 11/30/2013 Name of foundation A Employer identification number Milken Famil y Foundation 95-4073646 Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address ) Room /suite B Telephone number ( see instructions) 1250 Fourth St 3rd Floor 310-570-4800 City or town, state , and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending , check here ► Santa Monica CA 90401 G Check all that apply . J Initial return j initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations , check here ► Final return E Amended return 2 . Foreign organizations meeting the 85 % test, Address change Name change check here and attach computation ► H Check type of organization 0 Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947( a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust E] Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A). check here ► EJ I Fair market value of all assets at end J Accounting method Q Cash M Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination of year (from Part ll, col (c), Other (specify) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here ---------------------------- ► llne 16) ► $ 448,596,028 Part 1 column d must be on cash basis Revenue The (d ) Disbursements Analysis of and Expenses ( total of (a) Revenue and (b ) Net investment (c) Adjusted net for chartable amounts in columns (b). -

2006 Award Winners

Fight the Flood 6-8th Grade Division Award Winners 1st Place Best Overall Solution Most Spectacular Failure SOLFAN (Sick of Looking for a Name) FFA - Flood Fighting Association Egan Middle School Sutter Elementary School 2nd Place Best Overall Solution Teamwork Underminders 4chix Terman Middle School Castilleja School 3rd Place Best Overall Solution Peer Award: Best Team Name Geeks on the Go Dam, We’re Good! San Carlos Charter Learning Center McKinley Institute of Technology Fight the Flood 6-8th Grade Division Award Winners Device Performance Award Device Performance Award Flood Fighting Frogs Quicksand Merryhill School Jordan Middle School Engineering Process Award Engineering Process Award CHAK Squad Beach Girls Hillview Middle School Peninsula School Style and Presentation Award Style and Presentation Award Grit Gurlz Terman A Castilleja School Terman Middle School Fight the Flood 6-8th Grade Division Award Winners Judge’s Choice Award: Having the Most Fun Judge’s Choice Award: Most Efficient Bazooka Bubblegum Flamingos Terman Middle School Castilleja School Judge’s Choice Award: Most Spirit Judge’s Choice Award: Elegant Design Team Dragon Amoeba Fearless Flood Fighters Castilleja School Bullis Charter School Judge’s Choice Award: Venture Capitalist Judge’s Choice Award: Fastest Sand When the Levee Breaks SKAAMbag Terman Middle School Castilleja School Fight the Flood 9-12th Grade Division Award Winners 1st Place Best Overall Solution Most Spectacular Failure Team Blitzkreig Monta Vista ET54 Evergreen Valley High School Monta Vista -

2011 Summer Institute for Teachers

PUBLIC PROGRAMS 2011 SUMMER INSTITUTE FOR TEACHERS DESIGN-BASED SCHOLARSHIPS LEARNING AVAILABLE Empowering educators and preparing students for a changing world. THE SUMMER INSTITUTE FOR TEACHERS HOW DESIGN-BASED The rough scale model is a tool LEARNING WORKS to unlock students’ thinking and IS AN INTENSIVE FIVE-DAY INTERACTIVE Albert Einstein once said, “We problem-solving capabilities and WORKSHOP BASED ON A PROVEN AND cannot solve our problems with serves as a bridge to the academic AWARD-WINNING METHODOLOGY CALLED the same thinking we used when material they will later study in we created them.” This holds textbooks. Students learn how DESIGN-BASED LEARNING. true especially in education today to analyze and refine their ideas where the traditional methods are and how to test their thinking no longer as effective in engaging through both informal conversa- Design-Based Learning taps students’ and educating students. Design- tions and formal presentations. natural creativity to develop higher-level Based Learning “sneaks up on Leadership abilities, communica- learning” by giving teachers new tion skills and writing facility are thinking and enhance comprehension tools to inspire students’ innate significantly enhanced. of the K–12 curriculum. curiosity and create a fun, inter- active environment that develops AWARD-WINNING PROGRAM higher-level reasoning skills in Founded in 2002, Art Center’s No matter what grade level or subject the context of the standard K–12 Summer Institute for Teachers you teach, supplementing your current curriculum. received the 2006 Award of Merit in K–12 Architectural Education. methods with Design-Based Learning A teacher using Design-Based can make a dramatic difference in your Learning challenges students Design-Based Learning was to create “never-before-seen” developed by Doreen Nelson, classroom. -

California Association of Independent Schools Statement on Gun

XXXXX SFChronicle.com | Sunday, March 11, 2018 | A9 CaliforniaAssociation of IndependentSchools Statement on Gun Violence and School Safety As the Board of Directors of the California Association of Independent Schools, we join our Executive Director and the undersigned colleagues from our member schools —aswell as other independent, religious, and proprietaryschools throughout California —inanguish over the February14school shooting in Parkland, Florida. We extend our deepest sympathy to the families of the victims of this and everyschool shooting, and we stand in unwavering support of the survivors. We also stand in full solidarity with concerned educators nationwide. Today,school shootings are appallinglyroutine. Innocent lives of flourishingyoung people have been cut short, and students of everyage in countless communities are afraidtogotoschool. These students are our futureleaders. They and others, with amyriad of different perspectives, are also eager to change this paradigm by navigating our democratic processes, by engaging in respectful civic discourse, and by acting as catalysts for needed change, which we heartily applaud. We need to listen to their voices and respond to their pleas to make schools safe. As educators and as citizens, we are proud Republicans, Democrats, and Independents who believethatour countryneed notchoose between the rightful protection of responsiblegun ownership and the necessaryprevention of gun violence. We believe thatthe epidemic of gun violence in schools is an issue of non-partisan urgency, one thatdemands ahigher duty of care. We recall with admiration the ability to rise above partisanship on this issue displayed by two former Presidents, DemocratJimmy Carter and Republican Ronald Reagan, both of whom owned guns. In 1994, they worked together to help reduce the number of dangerous weapons available to private citizens. -

BOYS NOMINEES First Last School Name City State John Petty Mae

2017 McDonald's All American Games Nominees As of 1/13/2017 BOYS NOMINEES ALABAMA First Last School Name City State John Petty Mae Jemison Huntsville Alabama ARIZONA First Last School Name City State DeAndre Ayton Hillcrest Academy Phoenix Arizona Alex Barcello Corona Del Sol High School Tempe Arizona Dan Gafford El Dorado High School El Dorado Arizona Khalil Garland Parkview Arts Science Magnet High LIttle Rock Arizona Carson Pinter Seton Catholic High School Chandler Arizona Nigel Shadd Tri-City Christian Academy Chandler Arizona Luke Thompson Seton Catholic High School Chandler Arizona ARKANSAS First Last School Name City State Exavian Christon Hot Springs High School Hot Springs Arkansas KB Boaz Springdale High School Springdale Arkansas CALIFORNIA First Last School Name City State Aguir Agau Cathedral High School Los Angeles California Jemarl Baker Roosevelt High School Eastvale California LiAngelo Ball Chino Hills High School Chino Hills California Matts Benson Bishop O'Dowd High School Oakland California Miles Brookins Mater Dei High School Santa Ana California Walter Brostrum Bishop O'Dowd High School Oakland California Matthew Brown Arrowhead Christian Academy Redlands California Robert Brown Cathedral High School Los Angeles California Isom Butler Centennial High School Corona California Joey Calcaterra Marin High School Kentfield California Brandon Davis Alemany High School Mission Hills California Devante Doutrive Birmingham High School Lake Balboa California Reed Farley La Jolla High School La Jolla California Myles Franklin -

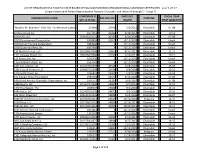

(BOE) Organizational Clearance Certificates- As of 1-27-17

LIST OF ORGANIZATIONS HOLDING STATE BOARD OF EQUALIZATION (BOE) ORGANIZATIONAL CLEARANCE CERTIFICATES - as of 1-27-17 (Organizations with Names Beginning with Numeric Characters and Letters A through C - Group 1) CORPORATE D DATE OCC FISCAL YEAR ORGANIZATION NAME BOE OCC NO. PURPOSE OR LLC ID NO. ISSUED FIRST QUALIFIED "Stephen M. Brammer" Post 705 The American Legion 233960 22442 3/2/2012 Charitable 07-08 10 Acre Ranch,Inc. 1977055 22209 4/30/2012 Charitable 10-11 1010 CAV, LLC 200615210122 20333 6/30/2008 Charitable 07-08 1010 Development Corporation 1800904 16010 12/11/2003 Charitable Unavl 1010 Senior Housing Corporation 1854046 3 12/11/2003 Charitable Unavl 1010 South Van Ness, Inc. 1897980 4 12/11/2003 Charitable Unavl 110 North D Street, LLC 201034810048 22857 9/15/2011 Charitable 11-12 1111 Chapala Street, LLC 200916810080 22240 2/24/2011 Charitable 10-11 112 Alves Lane, Inc. 1895430 5 12/11/2003 Charitable Unavl 1150 Webster Street, Inc. 1967344 6 12/11/2003 Charitable Unavl 11th and Jackson, LLC 201107610196 26318 12/8/2016 Charitable 15-16 12010 South Vermont LLC 200902710209 21434 9/9/2009 Charitable 10-11 1210 Scott Street, Inc. 2566810 19065 4/5/2006 Charitable 03-04 131 Steuart Street Foundation 2759782 20377 6/13/2008 Charitable 07-08 1420 Third Avenue Charitable Organization, Inc. 1950751 19787 10/3/2007 Charitable 07-08 1440 DevCo, LLC 201407210249 24869 9/1/2016 Charitable 15-16 1440 Foundation, The 2009237 24868 9/1/2016 Charitable 14-15 1440 OpCo, LLC 201405510392 24870 9/1/2016 Charitable 15-16 145 Ninth Street LLC -

Certified School List MM-DD-YY.Xlsx

Updated SEVP Certified Schools January 26, 2017 SCHOOL NAME CAMPUS NAME F M CITY ST CAMPUS ID "I Am" School Inc. "I Am" School Inc. Y N Mount Shasta CA 41789 ‐ A ‐ A F International School of Languages Inc. Monroe County Community College Y N Monroe MI 135501 A F International School of Languages Inc. Monroe SH Y N North Hills CA 180718 A. T. Still University of Health Sciences Lipscomb Academy Y N Nashville TN 434743 Aaron School Southeastern Baptist Theological Y N Wake Forest NC 5594 Aaron School Southeastern Bible College Y N Birmingham AL 1110 ABC Beauty Academy, INC. South University ‐ Savannah Y N Savannah GA 10841 ABC Beauty Academy, LLC Glynn County School Administrative Y N Brunswick GA 61664 Abcott Institute Ivy Tech Community College ‐ Y Y Terre Haute IN 6050 Aberdeen School District 6‐1 WATSON SCHOOL OF BIOLOGICAL Y N COLD SPRING NY 8094 Abiding Savior Lutheran School Milford High School Y N Highland MI 23075 Abilene Christian Schools German International School Y N Allston MA 99359 Abilene Christian University Gesu (Catholic School) Y N Detroit MI 146200 Abington Friends School St. Bernard's Academy Y N Eureka CA 25239 Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College Airlink LLC N Y Waterville ME 1721944 Abraham Joshua Heschel School South‐Doyle High School Y N Knoxville TN 184190 ABT Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School South Georgia State College Y N Douglas GA 4016 Abundant Life Christian School ELS Language Centers Dallas Y N Richardson TX 190950 ABX Air, Inc. Frederick KC Price III Christian Y N Los Angeles CA 389244 Acaciawood School Mid‐State Technical College ‐ MF Y Y Marshfield WI 31309 Academe of the Oaks Argosy University/Twin Cities Y N Eagan MN 7169 Academia Language School Kaplan University Y Y Lincoln NE 7068 Academic High School Ogden‐Hinckley Airport Y Y Ogden UT 553646 Academic High School Ogeechee Technical College Y Y Statesboro GA 3367 Academy at Charlemont, Inc. -

2016 Los Angeles County Science Fair Category Winners ANIMAL

2016 Los Angeles County Science Fair Category Winners Page 1 ANIMAL BIOLOGY (JR) J01 Mahmoud Alamad Al Huda Islamic School First Place Autism Listens! J0111 Split group: - Benjamin Hewitt Portola Highly Gifted Second Place Indication of Laterality in Magnet J0101 Bipedal Dinosaurs Using Gait Analysis from Split group: - Dinosaur Trackways Dani Chmait La Canada Preparatory Third Place The Triplet Fingerprint J0103 Study: Comparison of Fingerprint Patterns of Split group: - Identical and Non-Identical Co-Triplets Yolanda Carrion South Gate Middle School Honorable Mention The Effect that Salinity has J0117 on Sea Urchins Split group: - Henry Wilson St. Timothy School Honorable Mention The Thermal Conductivity J0106 of Animal Fibers Split group: - ANIMAL BIOLOGY (SR) S01 Jonnathan Sanchez Sarah Ross Science Fair First Place Galleria Mellonella Immune Jose De Anda (Senior Division) S0107 System Response to An Gissell Camarena Insecticide Split group: - Hongjia (Ashley) Yang Palisades Charter High Second Place Effects of Peptides on S0105 Memory Retainment Split group: - Dustin Hartuv Palos Verdes High School Third Place Movement of Cactus S0103 Wrens (Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus) Amid Split group: - Various Habitats Michael Liu Palos Verdes High School Honorable Mention Is RNA a Determining S0110 Factor in Memory in Dugesia tigrina Split group: - Jacob Kang Palos Verdes Peninsula Honorable Mention The Effects of Ocean High School S0106 Acidification on the Early Larval Development of Split group: - Haliotis rufescens Felicia Lin Palos Verdes High School Honorable Mention Ocean Acidification and S0104 Neurobiology: How the Aplysia californica Fits In Split group: - Maximo Guerrero Francisco Bravo Medical Honorable Mention The Effects of Different Magnet H.S S0109 Frequency Sounds on C. -

Last Name First Name Company Abogado Christine Irvington High

Last Name First Name Company Abogado Christine Irvington High School AbuMalhi Inez University of California, Los Angeles Achzet Kara CalArts Acosta Refugia University of California, Santa Barbara Acosta Robin Pinewood School Addison Garrett Chapman University Adegbile Tamar Cate School Agbay Drew San José State University Agbayani Shelden California Lutheran University Agree Ava University of San Francisco Aguilar Christian Chapman University Aguirre Sara University of Southern California Ahn Sung University of Arizona Alavez Shelly LAUSD Alderete Nancy University of California, Davis Alexander Evelyn Magellan College Counseling Allen Lea-Anne Macquarie University, Sydney Amaral Hope University of Southern California Anderson Brittany University of San Francisco Anderson Ashley The University of Alabama Apperson Ginger College-Fit, LLC Arechiga Xochitl Oakland Charter High School Arghi Sara Kaplan Test Prep Argueta Michelle Mount Saint Mary's University Arias Jesse University of California, Los Angeles Arora Sonia The Archer School for Girls Baker-BrousseauBrittany University of Southern California Balbin-Stacher Shirley University of California, San Diego Baltierra Johnny Armona School District Banks Michael Collegewise Baptista Chris The University of Alabama Barmore Brook Northern Arizona University Barnes Cheryl Discover Student Loans Barnes Kirsten Hanford West High School Barr Spencer Santa Barbara Senior High School Barsotti Gena Envision Academy of Arts & Tech Bartholomew Tracy Monte Vista Christian School Bartlett Nancy The College -

Boys & Girls Schools in Palo Alto

The Newsletter of the palo alto h i s t o r i c a l association Since 1913 March 2018 Volume 41, No 5 Te Palo Alto Historical Association presents Boys & Girls Schools in Palo Alto Sunday, March 4th, 2018, 2:00–4:00 pm Lucie Stern Community Center ~ 1305 Middlefeld Road, Palo Alto For our March program, PAHA Board Member Heather Allen examples of these early schools. Heather will also comment Pang will present the history of single-sex schools in this area, their on how educational trends have changed over the years. Many expansion in the 20th century to meet increased demand, the single-sex schools gave way to co-education, including Miss infuence of David Starr Jordan and Stanford University, and private Harker’s School and the Palo Alto Military Academy which school responses over the years to evolving educational trends. combined. Heather’s remarks will provide a window into Castilleja School, Manzanita Hall (later called the Palo understanding these evolving ideas, including coeducation Alto Military Academy), and Miss Harker’s School are all and redefned gender roles, in the context of single-sex schools. Castilleja School history teacher and archivist Heather Allen Pang was raised in Palo Alto. Heather graduated from Castilleja School, Wesleyan University, and earned a PhD in history at UC Davis. Harker Academy was once upon a time a girls’ school, while Castilleja, whose campus is pictured left in a 1930s map, has been educating women since 1907. Researching the (re-)naming of Palo Alto’s schools Recently I have been helping members of a excited by the new feld of electrical (radio) Palo Alto Unifd School District (PAUSD) engineering. -

Socioeconomic Diversity, Equity and Inclusion… in the SF Bay Area?!

5/23/2019 Socioeconomic diversity, equity and inclusion… in the SF Bay Area?! May 21, 2019 Schools Episcopal High School Maybeck High School Salesian College Preparatory Almaden Country School Escuela Bilingüe Internacional Menlo School Samuel Merritt University Athenian School FAIS, Portland Mirman School San Domenico School Aurora School FAIS, San Francisco Montessori Family School San Francisco Day School The Bay School of SF The Gillispie School Moses Brown School San Francisco Friends School Beaverton School District, OR Girls’ Middle School Mount Tamalpais School The San Francisco School Bentley School Gulliver Schools National Cathedral School SF University High School The Berkeley School The Hamlin School Oakwood School San Francisco Waldorf School Bishop O’Dowd High School The Harker School Oregon Episcopal School Sea Crest School Black Pine Circle Day School Head Royce School The Overlake School Seattle Academy Branson School Hillbrook School The Oxbow School Sonoma Academy Brentwood School Holy Names Academy Pacific Ridge School Sonoma Country Day School Buckley School International High School Park Day School Spruce Street School The Bush School Jewish Community HS of the Bay Peninsula School Stuart Hall for Boys The Carey School Kalmanovitz School of Ed, SMC The Potomac School The Thacher School Castilleja School Katherine Delmar Burke School Presidio Hill School Town School for Boys Cate School Kentfield School District, CA Principia Schools TvT Community Day School Catlin Gabel Keys School Prospect Sierra School University -

Premios De Oro – Level 1 2009 National Spanish Examination

Students who earned Premios de Oro – Level 1 2009 National Spanish Examination NOTE: The information in the columns below was extracted from the information section which teachers completed during the registration process for the National Spanish Examinations. Consequently, NSE is unable to correct any errors in spelling or capitalization. FIRST LAST SCHOOL TEACHER 001 – Alabama Grace Alexander Randolph School Prucha Deshane Alok The Altamont School Grass Shadi Awad The Altamont School Grass Pranav Bethala UMS-Wright Preparatory School Montalvo Rob Chappell Randolph School Prucha Jacob Cooke UMS-Wright Preparatory School Montalvo Emily Cutler Indian Springs School Mange Tina Etminan Indian Springs School Mange Cory Garfunkel UMS-Wright Preparatory School Montalvo Barbara Harle Spanish Fort High School Sebastiani Denton John The Altamont School Grass Lydia Moore Spanish Fort High School Sebastiani Hema Pingali Randolph School Prucha Jeromy Swann Phillips Preparatory School Rivera Bailey Vincent Randolph School Prucha 002 – Arizona Mitch Anhoury St. Michael's Parish Day School Stout Carina Arellano All Saints' Episcopal Day School Cox Elena Bauer St. Michael's Parish Day School Stout WILLIAM BIDWILL Brophy College Preparatory Higgins Bloebaum Bill All Saints' Episcopal Day School Cox Gates Bransen All Saints' Episcopal Day School Cox COLTON CHASE Brophy College Preparatory Higgins Alex Davonport Deer B=Valley High School Bondurant AUSTIN ENSOR Brophy College Preparatory Higgins Karla Esquer Deer Valley High School Jones CHRIS FRAME Brophy College Preparatory Higgins Ashley Hull All Saints' Episcopal Day School Shore Murphy Jackson All Saints' Episcopal Day School Cox Montanez- Samantha Johnson Tesseract School Ramirez Seltzer Kayla All Saints' Episcopal Day School Cox Johnson Lauren All Saints' Episcopal Day School Cox Dustin Little St.