The Celtic Languages in Contact

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revisiting the Insular Celtic Hypothesis Through Working Towards an Original Phonetic Reconstruction of Insular Celtic

Mind Your P's and Q's: Revisiting the Insular Celtic hypothesis through working towards an original phonetic reconstruction of Insular Celtic Rachel N. Carpenter Bryn Mawr and Swarthmore Colleges 0.0 Abstract: Mac, mac, mac, mab, mab, mab- all mean 'son', inis, innis, hinjey, enez, ynys, enys - all mean 'island.' Anyone can see the similarities within these two cognate sets· from orthographic similarity alone. This is because Irish, Scottish, Manx, Breton, Welsh, and Cornish2 are related. As the six remaining Celtic languages, they unsurprisingly share similarities in their phonetics, phonology, semantics, morphology, and syntax. However, the exact relationship between these languages and their predecessors has long been disputed in Celtic linguistics. Even today, the battle continues between two firmly-entrenched camps of scholars- those who favor the traditional P-Celtic and Q-Celtic divisions of the Celtic family tree, and those who support the unification of the Brythonic and Goidelic branches of the tree under Insular Celtic, with this latter idea being the Insular Celtic hypothesis. While much reconstructive work has been done, and much evidence has been brought forth, both for and against the existence of Insular Celtic, no one scholar has attempted a phonetic reconstruction of this hypothesized proto-language from its six modem descendents. In the pages that follow, I will introduce you to the Celtic languages; explore the controversy surrounding the structure of the Celtic family tree; and present a partial phonetic reconstruction of Insular Celtic through the application of the comparative method as outlined by Lyle Campbell (2006) to self-collected data from the summers of2009 and 2010 in my efforts to offer you a novel perspective on an on-going debate in the field of historical Celtic linguistics. -

Historical Background of the Contact Between Celtic Languages and English

Historical background of the contact between Celtic languages and English Dominković, Mario Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2016 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:149845 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-27 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i mađarskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Mario Dominković Povijesna pozadina kontakta između keltskih jezika i engleskog Diplomski rad Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Tanja Gradečak – Erdeljić Osijek, 2016. Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Odsjek za engleski jezik i književnost Diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i mađarskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Mario Dominković Povijesna pozadina kontakta između keltskih jezika i engleskog Diplomski rad Znanstveno područje: humanističke znanosti Znanstveno polje: filologija Znanstvena grana: anglistika Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Tanja Gradečak – Erdeljić Osijek, 2016. J.J. Strossmayer University in Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Teaching English as -

Old and Middle Welsh David Willis ([email protected]) Department of Linguistics, University of Cambridge

Old and Middle Welsh David Willis ([email protected]) Department of Linguistics, University of Cambridge 1 INTRODUCTION The Welsh language emerged from the increasing dialect differentiation of the ancestral Brythonic language (also known as British or Brittonic) in the wake of the withdrawal of the Roman administration from Britain and the subsequent migration of Germanic speakers to Britain from the fifth century. Conventionally, Welsh is treated as a separate language from the mid sixth century. By this time, Brythonic speakers, who once occupied the whole of Britain apart from the north of Scotland, had been driven out of most of what is now England. Some Brythonic-speakers had migrated to Brittany from the late fifth century. Others had been pushed westwards and northwards into Wales, western and southwestern England, Cumbria and other parts of northern England and southern Scotland. With the defeat of the Romano-British forces at Dyrham in 577, the Britons in Wales were cut off by land from those in the west and southwest of England. Linguistically more important, final unstressed syllables were lost (apocope) in all varieties of Brythonic at about this time, a change intimately connected to the loss of morphological case. These changes are traditionally seen as having had such a drastic effect on the structure of the language as to mark a watershed in the development of Brythonic. From this period on, linguists refer to the Brythonic varieties spoken in Wales as Welsh; those in the west and southwest of England as Cornish; and those in Brittany as Breton. A fourth Brythonic language, Cumbric, emerged in the north of England, but died out, without leaving written records, in perhaps the eleventh century. -

Breton Patronyms and the British Heroic Age

Breton Patronyms and the British Heroic Age Gary D. German Centre de Recherche Bretonne et Celtique Introduction Of the three Brythonic-speaking nations, Brittany, Cornwall and Wales, it is the Bretons who have preserved the largest number of Celtic family names, many of which have their origins during the colonization of Armorica, a period which lasted roughly from the fourth to the eighth centuries. The purpose of this paper is to present an overview of the Breton naming system and to identify the ways in which it is tied to the earliest Welsh poetic traditions. The first point I would like to make is that there are two naming traditions in Brittany today, not just one. The first was codified in writing during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and it is this system that has given us the official hereditary family names as they are recorded in the town halls and telephone directories of Brittany. Although these names have been subjected to marked French orthographic practices, they reflect, in a fossilized form, the Breton oral tradition as it existed when the names were first set in writing over 400 years ago. For this reason, these names often contain lexical items that are no longer understood in the modern spoken language. We shall return to this point below. The second naming system stems directly from the oral tradition as it has come down to us today. Unlike the permanent hereditary names, it is characterized by its ephemeral, personal and extremely flexible nature. Such names disappear with the death of those who bear them. -

New Approaches to Brittonic Historical Linguistics Abstracts

New Approaches to Brittonic Historical Linguistics Abstracts Gwen Awbery Aberystwyth University / University of Wales Trinity St David Historical dialectology and Welsh churchyards Memorial inscriptions on gravestones are an important source of evidence for dialect variation in Welsh in the past. They exist in truly enormous numbers, are found throughout the country, commemorating people from all walks of life, and the tradition of using Welsh in this context goes back to the mid-eighteenth century. Most revealing are the poems which form part of the inscription. Some have rhyme schemes which work only with very specific features of dialect; others are slightly garbled versions of poems by well-known writers, where the influence of dialect features can explain the changes made to the original. Since the location and date of each inscription is known, it appears possible to build up a picture of where and when these dialect features were in use. The situation is not totally straightforward, however, and there are inevitably problems which arise in dealing with this material, ranging from the need for extensive and time- consuming fieldwork, to the difficulties of reading inscriptions on worn and damaged stones, and the disconcerting tendency of some poems to show up in unexpected locations. Bernhard Bauer Maynooth University Close encounters of the linguistic kind: the Celtic glossing tradition The project Languages in Exchange: Ireland and her Neighbours (LeXiN) aims for a better understanding of the linguistic contacts between British Celtic and Irish in the early medieval period. The focal point of the investigation forms the “Celtic glossing tradition”, especially the vernacular glosses on the computistic works of Bede and on the Latin grammar of Priscian. -

The Celtic Languages in Contact

Late Modern Irish and the Dynamics of Language Change and Language Death Feargal Ó Béarra (National University of Ireland, Galway) 1. Introduction My comments are informed by the experience of the last 20-25 years, as someone who grew up in the Cois Fharraige Gaeltacht in south Conamara, and who has seen the language retreat further and further westwards and inwards as the Gaeltacht continues to dwindle. In these few years, I have also seen the last remaining pockets of Gaeltacht in areas such as Bearna, Na Forbacha, Mionlach, Leamhchoill, and Maigh Cuilinn all but disappear, never to return. There are few things in Ireland as complicated or as controversial as the language question. We agree on very little. Be that as it may, I believe we can all agree that the form of Irish spoken today is not that of 25 years ago, for example. What passes for Irish today would not have passed for Irish 25 years ago. Others will say to me that what passed for Irish 25 years ago would not have passed for Irish in 1958 when An Caighdeán Oifigiúil1 was published and so on. Of course, this should come as no surprise to us as languages are always in a state of flux. In most cases, except in the case of contemporary Irish, as I hope to show in this paper, language change is a fairly natural and unconscious devel- opment which forms an essential part of the life cycle of any language. Each generation creates its own version of the language it acquires from the previous generation. -

3. Celtic Languages

Freie Universität Berlin Fachbereich Philosophie und Geisteswissenschaften Appropriating New Technology for Minority Language Revitalization: The Welsh Case DISSERTATION zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) Vorgestellt von Mourad Ben Slimane Appropriating New Technology for Minority Language Revitalization Gutachter: 1. Prof. Dr. Gerhard Leitner 2. Prof. Dr. Carol W. Pfaff Disputation: Berlin, den 27.06.2008 2 Appropriating New Technology for Minority Language Revitalization Acknowledgments This dissertation would not have been written without the continuous support as well as great help of my dear Professor Gerhard Leitner. His expertise, understanding, and patience added considerably to my research experience. I would like to express my deep gratitude for him because it was his persistence and direction that encouraged me to complete my Ph.D. My special thanks goes out to Professor Carol W. Pfaff for giving me the opportunity to do a seminar on endangered languages at the John F. Kennedy Institute, which has been very useful for my thesis and professional experience. Thanks to Professor Peter Kunsmann, PD Dr.Volker Gast, and Dr. Florian Haas for kindly accepting to serve on my defense committee. I would also like to thank the Freie University of Berlin for the financial support that it provided me with to finish my research. The Welsh Language Board has also been very supportive in offering me recent literature on the development of Information Technology during my visit to Wales. Thanks to Grahame Davies from BBC Wales who provided me with many insights at different points in time with regard to Welsh new media and related matters. -

Where Are the Goalposts? Generational Change in the Use of Grammatical Gender in Irish

languages Article Where Are the Goalposts? Generational Change in the Use of Grammatical Gender in Irish Siobhán Nic Fhlannchadha * and Tina M. Hickey School of Psychology, University College Dublin, Dublin 4, Ireland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The Irish language is an indigenous minority language undergoing accelerated convergence with English against a backdrop of declining intergenerational transmission, universal bilingualism, and exposure to large numbers of L2 speakers. Recent studies indicate that the interaction of complex morphosyntax and variable levels of consistent input result in some aspects of Irish grammar having a long trajectory of acquisition or not being fully acquired. Indeed, for the small group of children who are L1 speakers of Irish, identifying which “end point” of this trajectory is appropriate against which to assess these children’s acquisition of Irish is difficult. In this study, data were collected from 135 proficient adult speakers and 306 children (aged 6–13 years) living in Irish-speaking (Gaeltacht) communities, using specially designed measures of grammatical gender. The results show that both quality and quantity of input appear to impact on acquisition of this aspect of Irish morphosyntax: even the children acquiring Irish in homes where Irish is the dominant language showed poor performance on tests of grammatical gender marking, and the adult performance on these tests indicate that children in Irish-speaking communities are likely to be exposed to input showing significant grammatical variability in Irish gender marking. The implications of these results will be discussed in terms of language convergence, and the need for intensive support for mother-tongue speakers of Irish. -

The Celtic Names of Cabus, Cuerden, and Wilpshire in Lancashire

THE CELTIC NAMES OF CABUS, CUERDEN, AND WILPSHIRE IN LANCASHIRE Andrew Breeze The three place-names discussed here, all in Lancashire, are of Celtic origin. They thus cast light on the pre-English inhabitants of the region, where a British dialect akin to Welsh was spoken until the Anglo-Saxon invasions of the late seventh century. The names are described in alphabetical order. 1. CABUS, NEAR LANCASTER Cabus is a parish (National Grid Reference SD 4848) eight miles south of Lancaster. Formerly a township in the parish of Garstang, it has no real centre, but lies on major north south routes of communication: the Lancaster canal runs along its western edge, the A6 down its middle, and the Glasgow- Euston railway beyond its eastern perimeter, which is formed mainly by the river Wyre. Ekwall, citing the name as 'Kaibal' in 1200-10 and 'Cayballes' in 1292, derived it from Old English ceg 'key', allegedly used in an earlier sense 'peg', plus unattested Old English ball 'rounded hill'. But he said the exact meaning of the name was unclear. A. D. Mills, who excludes many difficult names from his dictionary, omits Cabus. 1 This may 1 Eilert Ekwall, The concise Oxford dictionary of English place names (4th edn, Oxford, 1960), p. 80; A. D. Mills, A dictionary of English place-names (Oxford, 1991). 192 Andrew Breeze suggest dissatisfaction with Ekwall's explanation, in part because the Cabus region is flat and lacking in hills. It seems easier to derive the name from Celtic than from English. Here the obvious etymology for 'Kaibal' and 'Cayballes' is from an equivalent of Welsh ceubal 'boat, ferry boat, skiff, wherry, canoe'. -

The Brittonic Language in the Old North

1 The Brittonic Language in the Old North A Guide to the Place-Name Evidence Alan G. James Volume 1 Introduction, Bibliography etc. 2019 2 CONTENTS Preface, and The Author 3 Introduction 4 List of Abbreviations 42 Bibliography 56 Alphabetical List of Elements 92 Glossary of Middle or Modern Welsh Equivalents 96 Classified Lists of Elements 101 Guide to Pronunciation 114 Guide to the Elements Volume 2 Index of Place-Names Volume 3 3 Preface This work brings together notes on P-Celtic place-name elements to be found in northern England and southern Scotland assembled over a period of about twelve years. During this time, the author has received helpful information and suggestions from a great many individuals whose contributions are acknowledged in the text, but special mention must be made of Dr. Oliver Padel and Dr. Simon Taylor, both of whose encouragement and support, as well as rigorous criticism, have been invaluable throughout, though of course opinions, misunderstandings and mistakes in the work are those of the author. An earlier version of the material in the Guide to the Elements was housed on the website of the Scottish Place-Name Society as a database under the acronym BLITON; thanks are due to that organisation for making this possible, and to Dr. Jacob King, Dr. Christopher Yocum, Henry Gough-Cooper, and Dr. Peter Drummond, for undertaking various aspects of the technical work it entailed. Thanks are also due to John G. Wilkinson for very helpful proof-reading. The Author Dr. Alan G. James read English philology and mediaeval literature at Oxford, then spent thirty years in schoolteaching, training teachers and research in modern linguistics. -

On the Debate Over the Classification of the Language of the South-Western (SW) Inscriptions, Also Known As Tartessian

On the Debate over the Classification of the Language of the South-Western (SW) Inscriptions, also known as Tartessian John T. Koch University of Wales Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies I. Three and a half theories §1. Many linguists will be interested in Eric Hamp’s 2012 revision of his 1989 Indo-European family tree (both in Hamp 2013). For the present subject, the node called Northwest Indo-European1 is most relevant. The older and newer versions of this branch are redrawn below.2 1 Hamp’s names and descriptive terms for languages are indicated here with bold type rather than quotation marks, as quotation marks are used meaningfully on his trees. 2 Outside of the Italo-Celtic node I have simplified some of the details and omitted some of the bracketed annotations. [ 1 ] §2. The biggest change in this section of the tree is that what had been Northwest Indo-European in 1989 has become two sibling branches in 2012: (I) Northwest Indo-European and (II) Northern Indo-European (“mixture with non-Indo-European”). The latter branch (not included above) comprises: (1) “GERMANO-PREHELLENIC” (whence the siblings Germanic and Prehellenic (substrate geography)3); (2) Thracian, Dacian (as a single node); (3) Cimmerian; (4) Tocharian; and (5) “ADRIATIC- BALTO-SLAVIC” (whence the siblings (a) Balto-Slavic and (b) “ADRIATIC INDO-EUROPEAN” (the latter being the parent of (i) Albanian and (ii) “MESSAPO-ILLYRIAN”).4 Thus, one way in which the 2012 tree is different is that Phrygian alone is now seen as forming a subgroup with Italo-Celtic, whereas the 1989 tree had Italo-Celtic, Tocharian, Phrygian, Messapic, “Illyrian”, and Germanic, all as first-generation descendants of Northwest Indo-European, together with an “EASTERN NODE” (as a sibling in the same generation as Italo-Celtic and so on). -

1 the Celts and Their Languages

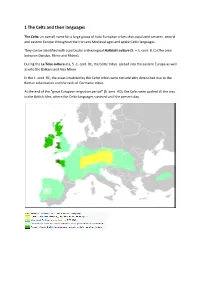

1 The Celts and their languages The Celts: an overall name for a large group of Indo-European tribes that populated western, central and eastern Europe throughout the Iron and Medieval ages and spoke Celtic languages. They can be identified with a particular archeological Hallstatt culture (8. – 5. cent. B. C) (The area between Danube, Rhine and Rhône). During the La Tène culture era, 5.-1. cent. BC, the Celtic tribes spread into the eastern Europe as well as into the Balkans and Asia Minor. In the 1. cent. BC, the areas inhabited by the Celtic tribes were considerably diminished due to the Roman colonization and the raids of Germanic tribes. At the end of the “great European migration period” (6. cent. AD), the Celts were pushed all the way to the British Isles, where the Celtic languages survived until the present day. The oldest roots of the Celtic languages can be traced back into the first half of the 2. millennium BC. This rich ethnic group was probably created by a few pre-existing cultures merging together. The Celts shared a common language, culture and beliefs, but they never created a unified state. The first time the Celts were mentioned in the classical Greek text was in the 6th cent. BC, in the text called Ora maritima written by Hecateo of Mileto (c. 550 BC – c. 476 BC). He placed the main Celtic settlements into the area of the spring of the river Danube and further west. The ethnic name Kelto… (Herodotus), Kšltai (Strabo), Celtae (Caesar), KeltŇj (Callimachus), is usually etymologically explainedwith the ie.