(Thallus) of a Lichen Photobiont(S) for Survival the Basic Structure of a Lichen Is Like That of the Popular Peanut Butter Cup Candy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Epiphytic Lichens and Lichenicolous Fungi From

LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004EPIPHYTIC LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LICHENS LJL©2004 AND LJL©2004 LICHENICOLOUS LJL©2004 LJL©2004 FUNGI LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004FROM LJL©2004 BAHÍA LJL©2004 HONDA LJL©2004 (VERAGUAS, LJL©2004 LJL©2004 PANAMA) LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 LJL©2004 -

Price's Scrub State Park

Price’s Scrub State Park Advisory Group Draft Unit Management Plan STATE OF FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Division of Recreation and Parks September 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................1 PURPOSE AND SIGNIFICANCE OF THE PARK ....................................... 1 Park Significance ................................................................................1 PURPOSE AND SCOPE OF THE PLAN..................................................... 2 MANAGEMENT PROGRAM OVERVIEW ................................................... 7 Management Authority and Responsibility .............................................. 7 Park Management Goals ...................................................................... 8 Management Coordination ................................................................... 9 Public Participation ..............................................................................9 Other Designations .............................................................................9 RESOURCE MANAGEMENT COMPONENT INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 11 RESOURCE DESCRIPTION AND ASSESSMENT..................................... 12 Natural Resources ............................................................................. 12 Topography .................................................................................. 12 Geology ...................................................................................... -

Komunitas Lumut Kerak (Lichens) Di Taman Wisata Alam Suranadi Kabupaten Lombok Barat

Komunitas Lumut Kerak (Lichens) Di Taman Wisata Alam Suranadi Kabupaten Lombok Barat Fitrianti*1, Faturrahman1, Sukiman1 1Department of Biology, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, University of Mataram, Jl. Majapahit No. 62, Mataram 83125, West Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia Tlp/Fax. 0370 646506, email: *[email protected] Abstrak Lumut Kerak merupakan simbiosis antara fungi dan alga atau cyanobacterium. yang bermanfaat sebagai bioresource, biondikator serta studi ekosistem. Dalam penelitian ini, beberapa aspek lumut kerak akan diteliti meliputi komposisi jenis, beserta jumlah individu tiap jenisnya dan nilai keanekaragaman lumut kerak. Penelitian ini bersifat deskriptif eksploratif yang telah dilaksanakan pada bulan Oktober-Desember 2016. Pengambilan data dilakukan menggunakan metode stratified random sampling dengan menempatkan 11 unit sampel berbentuk persegi. Pada tiap unit sampel, dipilih 12 pohon yang masing-masing akan dipasang 4 grid berukuran 50x10 cm. Identifikasi sampel dilakukan dengan mencocokkan (profile matching) ciri morfologi serta hasil spot test dengan buku identifikasi. Nilai keanekaragaman lumut kerak dianalisis dengan menggunakan Lichen Diversity Value serta Indeks Shannon dan Pielou. Dari hasil penelitian, 4 spesies ditemukan dari kelas Lecanoromycetes dan kelas Arthoniomycetes. Satu spesies tidak teridentifikasi. Nilai LDVj tertinggi 13,5 dari unit sampel blok perlindungan. Indeks nilai Shannon sebesar 0,57 dan Pielou sebesar 0,32. Kata kunci : TWA Suranadi, Lumut Kerak, Identifikasi, Nilai Keanekaragaman Abstract Lichen is a symbiosis between fungi and algae or cyanobacterium, which are useful as bioresource, bioindicator and ecosystem studies. In this research, several aspects of lichen will be examined including species composition along with the number of individuals of each species and the value of lichen diversity. This research is descriptive explorative which was conducted in October-December 2016. -

British Lichen Society Bulletin No

1 BRITISH LICHEN SOCIETY OFFICERS AND CONTACTS 2010 PRESIDENT S.D. Ward, 14 Green Road, Ballyvaghan, Co. Clare, Ireland, email [email protected]. VICE-PRESIDENT B.P. Hilton, Beauregard, 5 Alscott Gardens, Alverdiscott, Barnstaple, Devon EX31 3QJ; e-mail [email protected] SECRETARY C. Ellis, Royal Botanic Garden, 20A Inverleith Row, Edinburgh EH3 5LR; email [email protected] TREASURER J.F. Skinner, 28 Parkanaur Avenue, Southend-on-Sea, Essex SS1 3HY, email [email protected] ASSISTANT TREASURER AND MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY H. Döring, Mycology Section, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3AB, email [email protected] REGIONAL TREASURER (Americas) J.W. Hinds, 254 Forest Avenue, Orono, Maine 04473-3202, USA; email [email protected]. CHAIR OF THE DATA COMMITTEE D.J. Hill, Yew Tree Cottage, Yew Tree Lane, Compton Martin, Bristol BS40 6JS, email [email protected] MAPPING RECORDER AND ARCHIVIST M.R.D. Seaward, Department of Archaeological, Geographical & Environmental Sciences, University of Bradford, West Yorkshire BD7 1DP, email [email protected] DATA MANAGER J. Simkin, 41 North Road, Ponteland, Newcastle upon Tyne NE20 9UN, email [email protected] SENIOR EDITOR (LICHENOLOGIST) P.D. Crittenden, School of Life Science, The University, Nottingham NG7 2RD, email [email protected] BULLETIN EDITOR P.F. Cannon, CABI and Royal Botanic Gardens Kew; postal address Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3AB, email [email protected] CHAIR OF CONSERVATION COMMITTEE & CONSERVATION OFFICER B.W. Edwards, DERC, Library Headquarters, Colliton Park, Dorchester, Dorset DT1 1XJ, email [email protected] CHAIR OF THE EDUCATION AND PROMOTION COMMITTEE: position currently vacant. -

The Lichens 19

GALLOWAY: HUMBOLDT MOUNTAINS: THE LICHENS 19 V E GET A T ION S T U DIE SON TH E HUM B 0 L D T M 0 U N T A INS FIORDLAND PART 2: THE LICHENS D. J. GALLOWAY Biochemistry Department, University of Otago, Dunedin SUMMARY The commonest epiphytic foliose lichens in the beech forest are species of Sticta, some often A detailed list is given of the species of reaching great size: S. hirta, S. coronata, S. macrolichens collected from the western slopes of the Humboldt Mountains, Fiordland. The latifrons, S. filix. The most common epiphytic fruticose lichens are species of Usnea and composition and possible importance is dis- cussed of "sub-regional" lichen communities. Sphaerophorus. U snea xanthopoga and U. capiUacea are INTRODUCTION common on twigs of Nothofagus in well-lit situations either at the forest edge or at the The lichen flora of New Zealand is still top of the canopy. Sphaerophorus tener is a imperfectly known and details of its regional common epiphyte and other members of this composition are lacking for much of the genus represented in lesser numbers are several country. A survey of the rather scattered varieties of S. melanocarpus and occasionally literature reveals that very little taxonomic or S. stereocauloides. This, the largest species of ecological work has been done on the alpine the genus and the only one to have cephalodia, lichens. The great difficulty in field lichenology appears to be restricted to areas of high rainfall is accurate recognition of species, particularly in west and south-west areas of the South in alpine regions, where crustaceous lichens, Island. -

What Is a Lichen – a Prison Or an Opportunity? Lichens Cannot Be Classified As Plants

What is a lichen – a prison or an opportunity? Lichens cannot be classified as plants. They are associations between cup fungi ascomycetes plus either green algae (Trebouxia sp.) or cyanobacteria (e.g. Nostoc), members of three kingdoms outside the plant kingdom. Simon Schwendener discovered the dual nature of lichens in 1869 : Ascomycetes surround some single- celled green algae with a fibrous net to compel the new slaves to work for them, a view that was replaced with romanticized notion of a harmonious symbiosis. Mycobiont gets sugar alcohols from green algae or glucose + nitrogen from cyanobacteria, which are stored in an inacessible form (e.g. mannitol). Lichens Species & Diversity Lichens consist of a fungus (the mycobiont, mostly an ascomycete ) & a photosynthetic partner (the photobiont or phycobiont ), usually either a green alga (commonly Trebouxia ) or cyanobacterium (c. Nostoc ) All lichens have an upper cortex , which is a dense, protective skin of fungal tissue that acts l ike a blind that opens after watering . Below that is a photosynthetic layer, which can be a colony of either green algae or cyanobacteria. Then there is a layer of loose threads (hyphae) of the fungus, called the medulla or the medullary layer . Fructicose & Foliose lichens have a lower cortex , others just have an exposed medulla. Crustose lichens never have a lower cortex-their fungal layer attaches firmly to the substrate. What is that? Is that a plant? Is that a fungus? Is that a lichen? What the …halloh! Spanish moss (Tillandsia usneoides ) Usnea is a lichen (a composite organism closely resembles its namesake ( Usnea , or made from algae and fungi) and is referred beard lichen), but in fact it is not to as Old Man's Beard. -

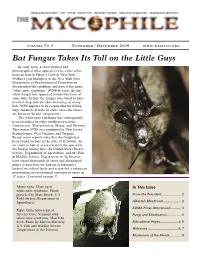

Bat Fungus Takes Its Toll on the Little Guys in Early 2006, a Caver Noticed and Photographed What Appeared to Be a Fine White Mass on Bats in Howe’S Cave in New York

50:3 N ⁄ D 2009 .. Bat Fungus Takes Its Toll on the Little Guys In early 2006, a caver noticed and photographed what appeared to be a fine white mass on bats in Howe’s Cave in New York. Within a year biologists at the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation documented the condition and gave it the name “white-nose syndrome” (WNS) because the fine white fungal mat appeared around the faces of some bats. In fact, the fungus was found to have invaded deep into the skin and wings of many bats. WNS appears to be responsible for killing large numbers of bats. In some caves the losses are between 90 and 100 percent! The white-nose syndrome has subsequently been identified in other northeastern states: Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maine, and Vermont. This winter WNS was confirmed in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Virginia. Recent news reports state that the fungus has been found on bats in the state of Delaware. In an effort to halt or at least restrict the spread of the fungus among bats, the United States Forest Service, Department of Agriculture, and the Fish & Wildlife Service, Department of the Interior, have closed thousands of caves and abandoned mines (where bats are known to hibernate) located on federal lands and requested a voluntary moratorium on recreational activities in caves in 17 states. (Continued on page 7) Above right: Close-up of In This Issue white-nose syndrome. Photo provided by Marc Bosch, U.S. From the President...................... 2 Field Service (Department of Agriculture). Alberta’s Mushroom .................. -

Piedmont Lichen Inventory

PIEDMONT LICHEN INVENTORY: BUILDING A LICHEN BIODIVERSITY BASELINE FOR THE PIEDMONT ECOREGION OF NORTH CAROLINA, USA By Gary B. Perlmutter B.S. Zoology, Humboldt State University, Arcata, CA 1991 A Thesis Submitted to the Staff of The North Carolina Botanical Garden University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Advisor: Dr. Johnny Randall As Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Certificate in Native Plant Studies 15 May 2009 Perlmutter – Piedmont Lichen Inventory Page 2 This Final Project, whose results are reported herein with sections also published in the scientific literature, is dedicated to Daniel G. Perlmutter, who urged that I return to academia. And to Theresa, Nichole and Dakota, for putting up with my passion in lichenology, which brought them from southern California to the Traingle of North Carolina. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………….4 Chapter I: The North Carolina Lichen Checklist…………………………………………………7 Chapter II: Herbarium Surveys and Initiation of a New Lichen Collection in the University of North Carolina Herbarium (NCU)………………………………………………………..9 Chapter III: Preparatory Field Surveys I: Battle Park and Rock Cliff Farm……………………13 Chapter IV: Preparatory Field Surveys II: State Park Forays…………………………………..17 Chapter V: Lichen Biota of Mason Farm Biological Reserve………………………………….19 Chapter VI: Additional Piedmont Lichen Surveys: Uwharrie Mountains…………………...…22 Chapter VII: A Revised Lichen Inventory of North Carolina Piedmont …..…………………...23 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………..72 Appendices………………………………………………………………………………….…..73 Perlmutter – Piedmont Lichen Inventory Page 4 INTRODUCTION Lichens are composite organisms, consisting of a fungus (the mycobiont) and a photosynthesising alga and/or cyanobacterium (the photobiont), which together make a life form that is distinct from either partner in isolation (Brodo et al. -

Fungal Diversity in Lichens: from Extremotolerance to Interactions with Algae

life Review Fungal Diversity in Lichens: From Extremotolerance to Interactions with Algae Lucia Muggia 1,* ID and Martin Grube 2 1 Department of Life Sciences, University of Trieste, via Licio Giorgieri 10, 34127 Trieste, Italy 2 Institute of Biology, Karl-Franzens University of Graz, Holteigasse 6, 8010 Graz, Austria; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +39-040-558-8825 Received: 11 April 2018; Accepted: 21 May 2018; Published: 22 May 2018 Abstract: Lichen symbioses develop long-living thallus structures even in the harshest environments on Earth. These structures are also habitats for many other microscopic organisms, including other fungi, which vary in their specificity and interaction with the whole symbiotic system. This contribution reviews the recent progress regarding the understanding of the lichen-inhabiting fungi that are achieved by multiphasic approaches (culturing, microscopy, and sequencing). The lichen mycobiome comprises a more or less specific pool of species that can develop symptoms on their hosts, a generalist environmental pool, and a pool of transient species. Typically, the fungal classes Dothideomycetes, Eurotiomycetes, Leotiomycetes, Sordariomycetes, and Tremellomycetes predominate the associated fungal communities. While symptomatic lichenicolous fungi belong to lichen-forming lineages, many of the other fungi that are found have close relatives that are known from different ecological niches, including both plant and animal pathogens, and rock colonizers. A significant fraction of yet unnamed melanized (‘black’) fungi belong to the classes Chaethothyriomycetes and Dothideomycetes. These lineages tolerate the stressful conditions and harsh environments that affect their hosts, and therefore are interpreted as extremotolerant fungi. Some of these taxa can also form lichen-like associations with the algae of the lichen system when they are enforced to symbiosis by co-culturing assays. -

Paul Stamets and Dusty Yao Donate to Mycoflora

Volume 58:2 March-April 2018 www.namyco.org Paul Stamets and Dusty Yao Donate to Mycoflora by David Rust Photo by Louie Schwartzberg by Louie Photo "We are honored to be able to give this modest contribution to help advance the study of mycology through the Mycoflora initiative.... Live long and sporulate !" We were thrilled to learn of a $10,000 donation by Paul Stamets and Dusty Yao to NAMA to support the North American Mycoflora Project. This contribution builds on the $24,000 matching fund set up by the Mycological Society of America and recent contributions to the matching fund by affiliated clubs and NAMA. Everyone accepts that the North American Mycoflora Project has been stalled since its inception in 2012 due to lack of funding. Substantive gifts like this not only give the work a short-term boost, but also establish a track record when applying for future fundraising. Dr. Tom Bruns at UC Berkeley has estimated that to complete a project of this size, $14-16 million will be needed. The Stamets-Yao gift will be designated for sequencing, offered by the lab of Dr. Todd Osmundson at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, and the lab of Dr. Rytas Vilgalys at Duke University in North Carolina. Sequencing is just the beginning, of course, with a next step of uploading data to a public website like GenBank to make this research available. Fungi Perfecti founder and president Paul Stamets has been a dedicated mycologist for over 40 years. Over this time, he has discovered and coauthored several new species of mushrooms, and pioneered countless techniques in the field of mushroom cultivation. -

Abstracts for IAL 6- ABLS Joint Meeting (2008)

Abstracts for IAL 6- ABLS Joint Meeting (2008) AÐALSTEINSSON, KOLBEINN 1, HEIÐMARSSON, STARRI 2 and VILHELMSSON, ODDUR 1 1The University of Akureyri, Borgir Nordurslod, IS-600 Akureyri, Iceland, 2Icelandic Institute of Natural History, Akureyri Division, Borgir Nordurslod, IS-600 Akureyri, Iceland Isolation and characterization of non-phototrophic bacterial symbionts of Icelandic lichens Lichens are symbiotic organisms comprise an ascomycete mycobiont, an algal or cyanobacterial photobiont, and typically a host of other bacterial symbionts that in most cases have remained uncharacterized. In the current project, which focuses on the identification and preliminary characterization of these bacterial symbionts, the species composition of the resident associate microbiota of eleven species of lichen was investigated using both 16S rDNA sequencing of isolated bacteria growing in pure culture and Denaturing Gradient Gel Electrophoresis (DGGE) of the 16S-23S internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region amplified from DNA isolated directly from lichen samples. Gram-positive bacteria appear to be the most prevalent, especially actinomycetes, although bacilli were also observed. Gamma-proteobacteria and species from the Bacteroides/Chlorobi group were also observed. Among identified genera are Rhodococcus, Micrococcus, Microbacterium, Bacillus, Chryseobacterium, Pseudomonas, Sporosarcina, Agreia, Methylobacterium and Stenotrophomonas . Further characterization of selected strains indicated that most strains ar psychrophilic or borderline psychrophilic, -

Fossil Usnea and Similar Fruticose Lichens from Palaeogene Amber

The Lichenologist (2020), 52, 319–324 doi:10.1017/S0024282920000286 Standard Paper Fossil Usnea and similar fruticose lichens from Palaeogene amber Ulla Kaasalainen1 , Jouko Rikkinen2,3 and Alexander R. Schmidt1 1Department of Geobiology, University of Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany; 2Finnish Museum of Natural History, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland and 3Organismal and Evolutionary Biology Research Programme, Faculty of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland Abstract Fruticose lichens of the genus Usnea Dill. ex Adans. (Parmeliaceae), generally known as beard lichens, are among the most iconic epiphytic lichens in modern forest ecosystems. Many of the c. 350 currently recognized species are widely distributed and have been used as bioin- dicators in air pollution studies. Here we demonstrate that usneoid lichens were present in the Palaeogene amber forests of Europe. Based on general morphology and annular cortical fragmentation, one fossil from Baltic amber can be assigned to the extant genus Usnea. The unique type of cortical cracking indirectly demonstrates the presence of a central cord that keeps the branch intact even when its cortex is split into vertebrae-like segments. This evolutionary innovation has remained unchanged since the Palaeogene, contributing to the considerable ecological flexibility that allows Usnea species to flourish in a wide variety of ecosystems and climate regimes. The fossil sets the minimum age for Usnea to 34 million years (late Eocene). While the other similar fossils from Baltic and Bitterfeld ambers cannot be definitely assigned to the same genus, they underline the diversity of pendant lichens in Palaeogene amber forests. Key words: Ascomycota, Baltic amber, Bitterfeld amber, lichen fossils (Accepted 16 April 2020) Introduction et al.