Working Paper Series 2016/47/TOM/EFE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Successful Players: Perspectives from the Western Business Education Sectors

Successful players: Perspectives from the Western business education sectors Internationalization as a key strategy of European Business Schools Professor Christian Delporte Director, Business School Services, EFMD Associate Director, Quality Services, EFMD European Business Schools and Internationalization Some data… FT Global MBA ranking data: % of International students 1. Bradford University School of Management, UK (100%) 2. Lancaster University Management School, UK (98%) 3. Rotterdam School of Management, Netherlands (98%) 4. IMD, Switzerland (97%) 5. University of Edinburgh Business School, UK (96%) 6. Hult International Business School, US / UK / UAE / C (94%) 7. University of Oxford: Saïd, UK (93%) 8. Aston Business School, UK (93%) 9. Insead, France / Singapore (92%) 10. Birmingham Business School, UK (92%) FT Global MBA ranking data: International Board membership 1. Vlerick Business School, Belgium (100%) 2. IESE Business School, Spain (87%) 3. IE Business School, Spain (81%) 4. Hult International Business School, US / UK / UAE / C (80%) 5. INCAE Business School, Costa Rica (80%) 6. IMD, Switzerland (79%) 7. Sungkyunkwan University SKK GSB, South Korea (79%) 8. Esade Business School, Spain (71%) 9. Insead, France / Singapore (70%) 10. London Business School, UK (70%) FT Global MBA ranking data: International mobility 1. IMD, Switzerland 2. HEC Paris, France 3. London Business School, UK 4. University of St Gallen, Switzerland 5. Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University Netherlands 6. IESE Business School, Spain 7. Vlerick Business School, Belgium 8. Hult International Business School, US / UK / UAE / C 9. National University of Singapore Business School, Singapore 10. Insead, France / Singapore FT Global MBA ranking data: % International faculty 1. IMD, Switzerland (98%) 2. -

Management and Organization Review

VOLUME 17 ISSUE 3 JULY 2021 ISSN: 1740-8776 Management and Organization Review Th e leading voice on indigenous management and organization research in China and all other transforming economies Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.40.40, on 01 Oct 2021 at 22:34:03, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/mor.2021.55 SPONSORS OF MANAGEMENT AND ORGANIZATION REVIEW International Association for Chinese Management Research Offi cers Founding President Vice-President and Program Chair for 2023 Anne S. Tsui University of Notre Dame Conference Peking University Wei Shen Arizona State University Past President Representatives at Large Ray Friedman Vanderbilt University Lori Qingyuan Yue Columbia Business School President Wu Liu Hong Kong Polytechnic University Zhi-Xue Zhang Peking University Zhijun Chen Shanghai University of Finance and Economics President Elect Hinrich Voss HEC Montreal Runtian Jing Shanghai Jiao Tong University Executive Director PhD Student Representatives Wei Zhang Peking University Danyang Zhu Fudan University Kaixian Mao Hong Kong University of Executive Secretary/Treasurer Science and Economics Lerong He State University of New York at Brockport Leadership of Peking University Leadership of Fudan University President Ping Hao President Ningsheng Xu Leadership of Guanghua School of Leadership of School of Management Fudan Management University Dean Qiao Liu Dean Xiongwen Lu Assosciate Deans Li’an Zhou Deputy Dean Yaopeng Li Liansheng Wu Shengping Zhang Executive Associate Dean Jian Zhou Ying Zhang Associate Deans Yimin Sun Li Ma Zhiwen Yin Zheng Zhang Changjiang Lu Ming Zheng Yaohua Ye Weitao Zhao Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. -

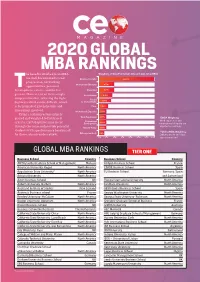

2020 GLOBAL MBA RANKINGS He Benefits Attached to an MBA Weighting of Data Points (Full-Time and Part-Time MBA)

2020 GLOBAL MBA RANKINGS he benefits attached to an MBA Weighting of Data Points (full-time and part-time MBA) are well documented: career Quality of Faculty: 34.95 % progression, networking International Diversity: 9.71% opportunities, personal Tdevelopment, salary... and the list Class Size: 9.71% goes on. However, in an increasingly Accreditation: 8.74% congested market, selecting the right Faculty business school can be difficult, which to Student Ratio: 7.76% is far from ideal given the time and Price: 5.83% investment involved. International Exposure: 4.85% Using a ranking system entirely geared and weighted to fact-based Work Experience: 4.85% *EMBA Weighting: Professional Work experience and criteria, CEO Magazine aims to cut Development: 4.85% international diversity are through the noise and provide potential adjusted accordingly. Gender Parity: 4.85% students with a performance benchmark **Online MBA Weighting: Delivery methods: 3.8% for those schools under review. Delivery mode and class 0 % 5 % 10 % 15 % 20 % 25 % 30 % 35 % size are removed. GLOBAL MBA RANKINGS TIER ONE Business School Country Business School Country AIX Marseille Graduate School of Management Monaco Emlyon Business School France American University: Kogod North America ESADE Business School Spain Appalachian State University* North America EU Business School Germany, Spain Ashland University North America and Switzerland Aston Business School UK Florida International University North America Auburn University: Harbert North America Fordham University North -

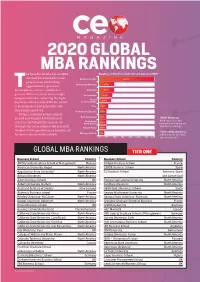

2020 GLOBAL MBA RANKINGS He Benefits Attached to an MBA Weighting of Data Points (Full-Time and Part-Time MBA)

2020 GLOBAL MBA RANKINGS he benefits attached to an MBA Weighting of Data Points (full-time and part-time MBA) are well documented: career Quality of Faculty: 34.95 % progression, networking International Diversity: 9.71% opportunities, personal Tdevelopment, salary... and the list Class Size: 9.71% goes on. However, in an increasingly Accreditation: 8.74% congested market, selecting the right Faculty business school can be difficult, which to Student Ratio: 7.76% is far from ideal given the time and Price: 5.83% investment involved. International Exposure: 4.85% Using a ranking system entirely geared and weighted to fact-based Work Experience: 4.85% *EMBA Weighting: Professional Work experience and criteria, CEO Magazine aims to cut Development: 4.85% international diversity are through the noise and provide potential adjusted accordingly. Gender Parity: 4.85% students with a performance benchmark **Online MBA Weighting: Delivery methods: 3.8% for those schools under review. Delivery mode and class 0 % 5 % 10 % 15 % 20 % 25 % 30 % 35 % size are removed. GLOBAL MBA RANKINGS TIER ONE Business School Country Business School Country AIX Marseille Graduate School of Management Monaco Emlyon Business School France American University: Kogod North America ESADE Business School Spain Appalachian State University* North America EU Business School Germany, Spain Ashland University North America and Switzerland Aston Business School UK Florida International University North America Auburn University: Harbert North America Fordham University North -

A League of Their Own: the Top 10 Master in Finance Programmes in Selected Categories As Rated by the 2011 Graduates

A league of their own: the Top 10 Master in Finance programmes in selected categories As rated by the 2011 graduates Top for corporate finance Top for hedge funds Top for international finance Top for investments Top for merger and acquisition Rank Business School Rank Business School Rank Business School Rank Business School Rank Business School 1 Peking University: Guanghua 1 Edhec Business School 1 HEC Paris 1 MIT: Sloan 1 ESCP Europe 2 Lancaster University Mgt School 2 Imperial College Business School 2 University of Oxford: Saïd 2 University of Rochester: Simon 2 Eada Business School Barcelona 3 ESCP Europe 3 HEC Lausanne 3 Brandeis University IBS 3 Boston College: Carroll 3 Università Bocconi 4 HEC Paris 4 IE Business School 4 Grenoble Graduate School of Business 4 Lancaster University Management School 4 Frankfurt SFM 5 Boston College: Carroll 5 MIT: Sloan 5 Kozminski University 5 Imperial College Business School 5 HEC Paris 6 University of Rochester: Simon 6 University of Oxford: Saïd 6 Leeds University Business School 6 University of Edinburgh Business School 6 IE Business School 7 Adam Smith Business School 7 City University: Cass 7 Henley Business School 7 Edhec Business School 7 Cranfield School of Management 8 Leeds University Business School 8 HEC Paris 8 Warwick Business School 8 Peking University: Guanghua 8 University of Oxford: Saïd 9 Vlerick Business School 9 Henley Business School 9 Edhec Business School 9 Skema Business School 9 City University: Cass 10 Stockholm School of Economics 10 Leeds University Business Schoolt -

INFORMATION SHEET for STUDENTS 2021-2022 the City Of

INFORMATION SHEET FOR STUDENTS 2021-2022 The city of Maastricht Maastricht, the oldest city in the Netherlands, gained international fame as the 'birthplace of the European Union' by hosting of the European Summit in 1991, and as the city where the Treaty of Maastricht was signed in 1992. Maastricht is centrally located in the heart of Europe, bordering Belgium (a brisk 47 minute walk or 11 minutes of vigorous bike riding away) and Germany (only 35 minutes by car), which means that Brussels is an hour-and- a-half away, Amsterdam two, Paris and Frankfurt three, and London four-and-a-half hours. There are nine airports within an hour's travel, where low cost carriers will take you to any European city in a heartbeat. Located in the southernmost tip of the country, it has a reputation for feeling rather non-Dutch. To many Dutch people it even feels as if they are abroad and no longer in the Netherlands! They join the flocks of other tourists who visit Maastricht to go shopping, to get a taste of its laid-back and friendly atmosphere, or to check out one of its 1,660 monumental buildings. Maastricht is a cosy city of around 122,000 inhabitants. Known for its vibrant student life, there are dozens of student associations and organisations devoted to everything from sustainability to sports, from drama to music, and to volunteering, studying, and partying. Maastricht is the perfect setting for a university city, with many festivals and events reflecting a diversity of cultural influences, from Maastricht's famous annual Carnival to experimental theatre, from thought-provoking lectures to lively music concerts. -

RETURN on INVESTMENT REPORT Full-Time MBA 2018

QS TopMBA.com RETURN ON INVESTMENT REPORT Full-Time MBA 2018 Unlocking the value of the world’s top business schools QS TopMBA.com Return on Investment Report 2018 Contents Introduction 3 Fast Facts 6 Payback Period 7 ı Shortest Payback Period: MBA, Global 7 ı Shortest Payback Period: MBA, US & Canada 8 ı Shortest Payback Period: MBA, Europe 9 ı Shortest Payback Period: MBA, Asia-Pacific 10 ı Payback Period: Business Masters 11 Salary Levels 12 ı Highest Salary: MBA, Global 12 ı Highest Salary: MBA, US & Canada 13 ı Highest Salary: MBA, Europe 14 ı Highest Salary: MBA, Asia-Pacific 15 ı Salary Levels: Business Masters 16 Salary Uplift 17 ı Biggest Salary Uplift: MBA, Global 17 ı Biggest Salary Uplift: MBA, US & Canada 18 ı Biggest Salary Uplift: MBA, Europe 19 ı Biggest Salary Uplift: MBA, Asia-Pacific 20 ı Salary Uplift: Business Masters 21 10-Year ROI 22 ı Highest 10-Year ROI: MBA, Global 22 ı Highest 10-Year ROI: MBA, US & Canada 23 ı Highest 10-Year ROI: MBA, Europe 24 ı Highest 10-Year ROI: MBA, Asia-Pacific 25 2 QS TopMBA.com Return on Investment Report 2018 Introduction What is the value of an MBA? This is a question many prospective MBA candidates around the world will be asking, before making an investment that can comfortably run into six figures when tuition and forgone salary are both taken into account. Indeed, at some top US schools, tuition alone can come to $200,000. Is it worth the investment? Well, we can’t really quantify the non-monetary value of an MBA, but we can certainly take a stab at working out some of the financials. -

INFORMATION SHEET for STUDENTS 2018-2019 the City Of

INFORMATION SHEET FOR STUDENTS 2018-2019 The city of Maastricht Maastricht, the oldest city in the Netherlands, gained international fame as the 'birthplace of the European Union' by hosting of the European Summit in 1991, and as the city where the Treaty of Maastricht was signed in 1992. Maastricht is centrally located in the heart of Europe, bordering Belgium (a brisk 47 minute walk or 11 minutes of vigorous bike riding away) and Germany (only 35 minutes by car), which means that Brussels is 1.5 hours away, Amsterdam 2 hours, Paris and Frankfurt 3 hours, and London 4.5 hours. Also, there are nine airports within an hour's travel, where low cost carriers will take you to any European city in a heartbeat. Located in the southernmost tip of the country, it has a reputation for being 'a bit foreign' even to other Dutch people. Many tourists visit Maastricht to go shopping, to get a taste of its convivial atmosphere, or to check out one of its 1,660 monumental buildings. Maastricht is a cosy city of around 122,000 inhabitants. Known for its vibrant student life, there are dozens of student associations and organisations devoted to everything from sustainability to sports, from drama to music, and to volunteering, studying, and partying. Maastricht is the perfect setting for a university city, with many festivals and events reflecting a diversity of cultural influences, from Maastricht's famous annual Carnival to experimental theatre, from thought-provoking lectures to lively music concerts. Going out to eat or having a drink at one of our many bars and cafes, especially outside, is a favourite pastime of both students and locals. -

The Top 10 Master in Finance Programmes in Selected Categories As Rated by the 2012 Graduates

A league of their own: the Top 10 Master in Finance programmes in selected categories As rated by the 2012 graduates Top for corporate finance Top for hedge funds Top for international finance Top for investments Top for merger and acquisition Rank Business School Rank Business School Rank Business School Rank Business School Rank Business School 1 ESCP Europe 1 City University: Cass 1 HEC Paris 1 Tulane University: Freeman 1 ESCP Europe 2 Nova School of Business and Economics 2 Henley Business School 2 Brandeis University IBS 2 Nova School of Business and Economics 2 City University: Cass 3 Kozminski University 3 Imperial College Business School 3 Eada Business School Barcelona 3 Universidad Adolfo Ibañez 3 HEC Paris 4 HEC Paris 4 MIT: Sloan 4 Esade Business School 4 Peking University: Guanghua 4 Washington University: Olin 5 IE Business School 5 ESCP Europe 5 Essec Business School 5 Edhec Business School 5 Frankfurt SFM 6 Washington University: Olin 6 Essec Business School 6 Leeds University Business School 6 ESCP Europe 6 Università Bocconi 7 Stockholm School of Economics 7 IE Business School 7 Kozminski University 7 University of Edinburgh Business School 7 Eada Business School Barcelona 8 Lund University SEM 8 Skema Business School 8 Warwick Business School 8 University of Hong Kong 8 IE Business School 9 University of Oxford: Saïd 9 Aston Business School 9 University of Bath SoM 9 Tilburg University 9 Esade Business School 10 Lancaster University Management School 10 Nottingham University Business School 10 Aston Business School -

2020 Business Accreditation Standards in Service to AACSB’S Membership

d Effective July 28, 2020 1 2020 GUIDING PRINCIPLES AND STANDARDS FOR BUSINESS ACCREDITATION ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AACSB wishes to recognize the members of the Business Accreditation Task Force (BATF), who worked tirelessly over nearly two years and collectively provided thousands of hours of thought leadership to develop standards that reflect the collective interest of the Accreditation Council. The BATF was formulated and charged by 2018–19 AACSB Board of Directors chair Caryn L. Beck-Dudley, then dean of the Leavey School of Business at Santa Clara University. Co-Chairs Nancy A. Bagranoff, University Professor, Accounting, University of Richmond Geoff Perry, AACSB Executive Vice President and Chief Officer of Asia Pacific Members Neil S. Braun, Dean Emeritus, Pace University Marion Debruyne, Dean, Vlerick Business School Irineu G. N. Gianesi, Dean of Academic Affairs, Insper Instituto de Ensino e Pesquisa William H. Glick, H. Joe Nelson III Professor of Management, Rice University Charles Iacovou, Sisel Distinguished Dean of Business, Wake Forest University Eli Jones, Dean, Professor, and Lowry and Peggy Mays Eminent Scholar, Texas A&M University Jikyeong Kang, President, Dean, and MVP Professor of Marketing, Asian Institute of Management Susan Lehrman, Dean, Rowan University Stefanie A. Lenway, Dean, University of St. Thomas-Minnesota Peter Lindstrom, Dean, External Relations, University of St. Gallen Michel Patry, Chief Executive Officer, Fondation HEC Montréal Joyce A. Strawser, Dean, Seton Hall University Peter A. Todd, Director General and Dean, HEC Paris Lin Zhou, Dean, The Chinese University of Hong Kong AACSB Staff Caryn L. Beck-Dudley, President and Chief Executive Officer Stephanie Bryant, Executive Vice President and Chief Accreditation Officer Suzanne Mintz, Assistant Vice President of Accreditation Strategy and Policy 2 2020 GUIDING PRINCIPLES AND STANDARDS FOR BUSINESS ACCREDITATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS FY 2019–20 Chair John A. -

EXPANDING YOUR PALETTE an EXPLORATION of RECRUITMENT & COLLABORATION THROUGH DESIGN Connect with Us! #Csearotterdam

EXPANDING YOUR PALETTE AN EXPLORATION OF RECRUITMENT & COLLABORATION THROUGH DESIGN Connect with us! #CSEARotterdam MBA Career Services & Employer Alliance @MBACSEA MBA Career Services & Employer Alliance @MBACSEA Welcome Welcome to Rotterdam! On behalf of the MBA CSEA Board of Directors and the 2018 European Con- ference Committee, welcome to Rotterdam! I hope you are as excited as I am about “Expanding Your Palette,” focused on “An Exploration of Recruit- ment and Collaboration Through Design.” Collaboration and innovation are critical to our success, so this conference presents best practices and resources to help us grow and evolve in these changing times. Our co-chairs, Cecilia Fri- grams ever. Thanks to them, we can all expect to have etsch of Stockholm School a fun, educational and memorable conference filled of Economics, Ana Herranz of IE Business School and with new friends, new ideas and new discoveries. Jelda Veninga of TIAS School for Business & Society, I look forward to getting to know all of you at have done an excellent job with their hard-working the event! committee of putting together one of our best pro- Jamie Belinne, President, MBA CSEA Welcome to our 2018 European Conference! It’s only fitting that we are in Rotterdam – a city known for its architecture and innovation – as we explore how design can change the way we think and learn. I’m looking forward to spending the next few days with all of you in this fabulous city as we connect with colleagues, meet new people, share innovations and solve common challenges. The team behind the design and much-deserved message of appreciation. -

Vlerick Business School

Vlerick Business School As Associate or Full Professor in Entrepreneurship Vlerick Business School Associate/Full Professor in Entrepreneurship Executive Summary Vlerick Business School is an international business school in the heart of Europe. It is consistently ranked among Europe’s best business schools, with some 500 students enrolling for Masters and MBA programmes each year at its campuses in Brussels, Ghent and Leuven, and in Beijing. In addition to this, over 5,000 executives attend its management development programmes. Vlerick belongs to a select group of business schools in the world that hold all three major international accreditation labels in the world of management education: EQUIS, AMBA and AACSB. Thus, it is clearly recognised for an education which is academically sound, fosters an international mind-set, addresses leading-edge managerial issues, and develops an entrepreneurial attitude. It is a place of transformation where people and organisations come to challenge themselves, the status quo and the changing world around them. The School is now looking to appoint an Associate or Full Professor in Entrepreneurship to join a team of faculty members and researchers active in Entrepreneurship. The successful candidate will have a PhD in the area of Entrepreneurship with a focus on high-growth or technology entrepreneurship. Alongside this, candidates should demonstrate evidence of strong research capacity, the ability to merge fundamental theoretical knowledge with practice relevance, excellent teaching achievements, and ideally bringing an innovative approach to learning and an interest in exploring the application of digital topics and techniques within their academic activity. This post represents a challenging job within an international, dynamic, and professional environment with strong business networks and an emphasis on the synergies between science and practice.