Industrial Relations in the Oil Industry in Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oil Refining in Mexico and Prospects for the Energy Reform

Articles Oil refining in Mexico and prospects for the Energy Reform Daniel Romo1 1National Polytechnic Institute, Mexico. E-mail address: [email protected] Abstract: This paper analyzes the conditions facing the oil refining industry in Mexico and the factors that shaped its overhaul in the context of the 2013 Energy Reform. To do so, the paper examines the main challenges that refining companies must tackle to stay in the market, evaluating the specific cases of the United States and Canada. Similarly, it offers a diagnosis of refining in Mexico, identifying its principal determinants in order to, finally, analyze its prospects, considering the role of private initiatives in the open market, as well as Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), as a placeholder in those areas where private enterprises do not participate. Key Words: Oil, refining, Energy Reform, global market, energy consumption, investment Date received: February 26, 2016 Date accepted: July 11, 2016 INTRODUCTION At the end of 2013, the refining market was one of stark contrasts. On the one hand, the supply of heavy products in the domestic market proved adequate, with excessive volumes of fuel oil. On the other, the gas and diesel oil demand could not be met with production by Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex). The possibility to expand the infrastructure was jeopardized, as the new refinery project in Tula, Hidalgo was put on hold and the plan was made to retrofit the units in Tula, Salamanca, and Salina Cruz. This situation constrained Pemex's supply capacity in subsequent years and made the country reliant on imports to supply the domestic market. -

Climate and Energy Benchmark in Oil and Gas Insights Report

Climate and Energy Benchmark in Oil and Gas Insights Report Partners XxxxContents Introduction 3 Five key findings 5 Key finding 1: Staying within 1.5°C means companies must 6 keep oil and gas in the ground Key finding 2: Smoke and mirrors: companies are deflecting 8 attention from their inaction and ineffective climate strategies Key finding 3: Greatest contributors to climate change show 11 limited recognition of emissions responsibility through targets and planning Key finding 4: Empty promises: companies’ capital 12 expenditure in low-carbon technologies not nearly enough Key finding 5:National oil companies: big emissions, 16 little transparency, virtually no accountability Ranking 19 Module Summaries 25 Module 1: Targets 25 Module 2: Material Investment 28 Module 3: Intangible Investment 31 Module 4: Sold Products 32 Module 5: Management 34 Module 6: Supplier Engagement 37 Module 7: Client Engagement 39 Module 8: Policy Engagement 41 Module 9: Business Model 43 CLIMATE AND ENERGY BENCHMARK IN OIL AND GAS - INSIGHTS REPORT 2 Introduction Our world needs a major decarbonisation and energy transformation to WBA’s Climate and Energy Benchmark measures and ranks the world’s prevent the climate crisis we’re facing and meet the Paris Agreement goal 100 most influential oil and gas companies on their low-carbon transition. of limiting global warming to 1.5°C. Without urgent climate action, we will The Oil and Gas Benchmark is the first comprehensive assessment experience more extreme weather events, rising sea levels and immense of companies in the oil and gas sector using the International Energy negative impacts on ecosystems. -

Integrating Into Our Strategy

INTEGRATING CLIMATE INTO OUR STRATEGY • 03 MAY 2017 Integrating Climate Into Our Strategy INTEGRATING CLIMATE INTO OUR STRATEGY • 03 CONTENTS Foreword by Patrick Pouyanné, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, Total 05 Three Questions for Patricia Barbizet, Lead Independent Director of Total 09 _____________ SHAPING TOMORROW’S ENERGY Interview with Fatih Birol, Executive Director of the International Energy Agency 11 The 2°C Objective: Challenges Ahead for Every Form of Energy 12 Carbon Pricing, the Key to Achieving the 2°C Scenario 14 Interview with Erik Solheim, Executive Director of UN Environment 15 Oil and Gas Companies Join Forces 16 Interview with Bill Gates, Breakthrough Energy Ventures 18 _____________ TAKING ACTION TODAY Integrating Climate into Our Strategy 20 An Ambition Consistent with the 2°C Scenario 22 Greenhouse Gas Emissions Down 23% Since 2010 23 Natural Gas, the Key Energy Resource for Fast Climate Action 24 Switching to Natural Gas from Coal for Power Generation 26 Investigating and Strictly Limiting Methane Emissions 27 Providing Affordable Natural Gas 28 CCUS, Critical to Carbon Neutrality 29 A Resilient Portfolio 30 Low-Carbon Businesses to Become the Responsible Energy Major 32 Acquisitions That Exemplify Our Low-Carbon Strategy 33 Accelerating the Solar Energy Transition 34 Affordable, Reliable and Clean Energy 35 Saft, Offering Industrial Solutions to the Climate Change Challenge 36 The La Mède Biorefinery, a Responsible Transformation 37 Energy Efficiency: Optimizing Energy Consumption 38 _____________ FOCUS ON TRANSPORTATION Offering a Balanced Response to New Challenges 40 Our Initiatives 42 ______________ OUR FIGURES 45 04 • INTEGRATING CLIMATE INTO OUR STRATEGY Total at a Glance More than 98,109 4 million employees customers served in our at January 31, 2017 service stations each day after the sale of Atotech A Global Energy Leader No. -

Measuring the Importance of Oil-Related Revenues in Total Fiscal Income for Mexico ⁎ Manuel Lorenzo Reyes-Loya, Lorenzo Blanco

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repositorio Academico Digital UANL Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Energy Economics 30 (2008) 2552–2568 www.elsevier.com/locate/eneco Measuring the importance of oil-related revenues in total fiscal income for Mexico ⁎ Manuel Lorenzo Reyes-Loya, Lorenzo Blanco Facultad de Economía, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Loma Redonda #1515 Pte., Col. Loma Larga, C.P. 64710, Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico Received 28 February 2007; received in revised form 8 February 2008; accepted 9 February 2008 Available online 20 February 2008 Abstract Revenues from oil exports are an important part of government budgets in Mexico. A time-series analysis is conducted using monthly data from 1990 to 2005 examining three different specifications to determine how international oil price fluctuations and government income generated from oil exports influence fiscal policy in Mexico. The behavior of government spending and taxation is consistent with the spend-tax hypothesis. The results show that there is an inverse relationship between oil-related revenues and tax revenue from non-oil sources. Fiscal policy reform is urgently needed in order to improve tax collection as oil reserves in Mexico become more and more depleted. © 2008 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. JEL classification: O13; O54; Q32; Q48 Keywords: Fiscal policy; Mexico; Oil price fluctuations; Unexpected oil revenues 1. Introduction Given its location and climate, Mexico is endowed with a wide variety of natural resources. Oil is one of the resources that has played an important role in both the economic and the political development of Mexico (Everhart and Duval-Hernandez, 2001; Morales et al., 1988). -

Shell QRA Q2 2021

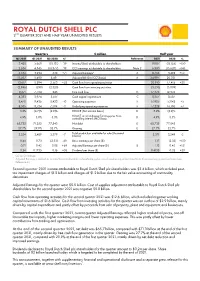

ROYAL DUTCH SHELL PLC 2ND QUARTER 2021 AND HALF YEAR UNAUDITED RESULTS SUMMARY OF UNAUDITED RESULTS Quarters $ million Half year Q2 2021 Q1 2021 Q2 2020 %¹ Reference 2021 2020 % 3,428 5,660 (18,131) -39 Income/(loss) attributable to shareholders 9,087 (18,155) +150 2,634 4,345 (18,377) -39 CCS earnings attributable to shareholders Note 2 6,980 (15,620) +145 5,534 3,234 638 +71 Adjusted Earnings² A 8,768 3,498 +151 13,507 11,490 8,491 Adjusted EBITDA (CCS basis) A 24,997 20,031 12,617 8,294 2,563 +52 Cash flow from operating activities 20,910 17,415 +20 (2,946) (590) (2,320) Cash flow from investing activities (3,535) (5,039) 9,671 7,704 243 Free cash flow G 17,375 12,376 4,383 3,974 3,617 Cash capital expenditure C 8,357 8,587 8,470 9,436 8,423 -10 Operating expenses F 17,905 17,042 +5 8,505 8,724 7,504 -3 Underlying operating expenses F 17,228 16,105 +7 3.2% (4.7)% (2.9)% ROACE (Net income basis) D 3.2% (2.9)% ROACE on an Adjusted Earnings plus Non- 4.9% 3.0% 5.3% controlling interest (NCI) basis D 4.9% 5.3% 65,735 71,252 77,843 Net debt E 65,735 77,843 27.7% 29.9% 32.7% Gearing E 27.7% 32.7% Total production available for sale (thousand 3,254 3,489 3,379 -7 boe/d) 3,371 3,549 -5 0.44 0.73 (2.33) -40 Basic earnings per share ($) 1.17 (2.33) +150 0.71 0.42 0.08 +69 Adjusted Earnings per share ($) B 1.13 0.45 +151 0.24 0.1735 0.16 +38 Dividend per share ($) 0.4135 0.32 +29 1. -

Statoil Business Update

Statoil US Onshore Jefferies Global Energy Conference, November 2014 Torstein Hole, Senior Vice President US Onshore competitively positioned 2013 Eagle Ford Operator 2012 Marcellus Operator Williston Bakken 2011 Stamford Bakken Operator Marcellus 2010 Eagle Ford Austin Eagle Ford Houston 2008 Marcellus 1987 Oil trading, New York Statoil Office Statoil Asset 2 Premium portfolio in core plays Bakken • ~ 275 000 net acres, Light tight oil • Concentrated liquids drilling • Production ~ 55 kboepd Eagle Ford • ~ 60 000 net acres, Liquids rich • Liquids ramp-up • Production ~34 koepd Marcellus • ~ 600 000 net acres, Gas • Production ~130 kboepd 3 Shale revolution: just the end of the beginning • Entering mature phase – companies with sustainable, responsible development approach will be the winners • Statoil is taking long term view. Portfolio robust under current and forecast price assumptions. • Continuous, purposeful improvement is key − Technology/engineering − Constant attention to costs 4 Statoil taking operations to the next level • Ensuring our operating model is fit for Onshore Operations • Doing our part to maintain the company’s capex commitments • Leading the way to reduce flaring in Bakken • Not just reducing costs – increasing free cash flow 5 The application of technology Continuous focus on cost, Fast-track identification, Prioritised development of efficiency and optimisation of development & implementation of potential game-changing operations short-term technology upsides technologies SHORT TERM – MEDIUM – LONG TERM • Stage -

The Bilingual Review La Revista Bilingüe

The Bilingual Review VOL. XXXIV l NO 2 l OCTOBER 2019 La Revista Bilingüe OPEN-ACCESS, PEER-REVIEWED/ACCESO ABIERTO, JURADO PROFESIONAL From Midvale to Mexico and Back Manuel Romero Independent Researcher Abstract: From Mexico to Midvale and Back, is the story of the amazing journey as a result of being selected for the Becas Para Aztlán program in August 1979. I tell of where I grew up, the events that took me from a boy without goals after high school to graduate school and beyond. The wonderful people I met, who became friends and remain friends. This is the story of a young Chicano who’s family was in this country when the Pilgrims were the illegal aliens. The story of an amazing family who did not always understand my choices but were always supportive. Keywords Casa Aztlán, Becario, Chicano Movement Bilingual Review/Revista Bilingüe (BR/RB) ©2019, Volume 34, Number 2 1 Origins The story of Casa Aztlán begins long before I arrived in Mexico City on August 2, 1979. A few years earlier Mexico discovered a huge oil reserve off their eastern coast. Little did I know this discovery would propel me to a whole new and exciting cultural, political and educational journey. It was an experience that would lead to new opportunities, opportunities I had heard were only possible for Anglos in the United States; Graduate school, WOW, I’m going to graduate school and at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, the most prestigious university in Latin America. The new, and unexpected path would bring me to where I am today began long before I believed college was possible. -

Biofuel Industry and Future Sustainability in Mexico

BIOFUEL INDUSTRY AND FUTURE SUSTAINABILITY IN MEXICO JESUS PULIDO-CASTAÑON JAIME MARTINEZ-GARCIA School of Economics - Universidad Autonoma de San Luis Potosi INTRODUCTION Since the nationalization of the oil industry in Mexico, oil resources have played a critical role for the fueling of important economic sectors as well as in the funding of government spending (Blanchard, 2005). In the year of 1978, president Lopez-Portillo made a call to the population to “manage the abundance” referring to the large reserves of crude oil that were available under the national soil (Pazos, 1979). During the last decade, however, oil resources in Mexico have started to show signs of depletion (Blanchard, 2005) and as a result the future of the country´s economic development might be at stake. The situation of depleting oil resources could serve as an incentive to redirect the current process of energy production towards more sustainable and clean alternatives. In this context, this paper analyzes the opportunities presented by the development of a biofuel industry based on resources and technologies available in the country. THE IMPORTANCE OF OIL RESOURCES IN MEXICO During the period of 2000-2010, the production of energy in Mexico has been carried out through the exploitation of natural resources both renewable and non-renewable. In this regard, an important aspect is that crude oil has been the most significant source of energy in the country, producing approximately 90.5% (9,867 pentajoules) or nine tenths of the total energy production (SIE, 2012). In this context, from the total of energy consumed 26.62% was used by the industrial sector, 24.64% was used by the transportation sector, and the remaining 49% was divided among the energy transformation sector (oil and electricity) as well as the residential, commercial and public sectors (SIE, 2012). -

Oil for As Long As Most Americans Can Remember, Gasoline Has Been the Only Fuel They Buy to Fill up the Cars They Drive

Fueling a Clean Transportation Future Chapter 2: Gasoline and Oil For as long as most Americans can remember, gasoline has been the only fuel they buy to fill up the cars they drive. However, hidden from view behind the pump, the sources of gasoline have been changing dramatically. Gasoline is produced from crude oil, and over the last two de- cades the sources of this crude have gotten increasingly di- verse, including materials that are as dissimilar as nail polish remover and window putty. These changes have brought rising global warming emissions, but not from car tailpipes. Indeed, tailpipe emissions per mile are falling as cars get more efficient. Rather, it is the extraction and refining of oil that are getting dirtier over time. The easiest-to-extract sources of oil are dwindling, and the oil industry has increasingly shifted its focus to resources that require more energy-intensive extraction or refining methods, resources that were previously too expensive and risky to be developed. These more challenging oils also result Yeulet © iStock.com/Cathy in higher emissions when used to produce gasoline (Gordon 2012). The most obvious way for the United States to reduce the problems caused by oil use is to steadily reduce oil con- sumption through improved efficiency and by shifting to cleaner fuels. But these strategies will take time to fully im- plement. In the meantime, the vast scale of ongoing oil use Heat-trapping emissions from producing transportation fuels such as gasoline are on the rise, particularly emissions released during extracting and refining means that increases in emissions from extracting and refin- processes that occur out of sight, before we even get in the car. -

Local Content Policy and Industrial

2017/18 Knowledge Sharing Program with Mexico (II): Local Content Policy and Industrial Development for the Energy Sector 2017/18 Knowledge Sharing Program with Mexico (II) 2017/18 Knowledge Sharing Program with Mexico (II) Project Title Local Content Policy and Industrial Development for the Energy Sector Prepared by Korea Development Institute (KDI) Supported by Ministry of Economy and Finance (MOEF), Republic of Korea Prepared for The Government of the United Mexican States In Cooperation with Mexican Agency for International Development Cooperation (AMEXCID), Mexico Secretariat of Economy, Mexico Program Directors Youngsun Koh, Executive Director, Center for International Development (CID), KDI Kwangeon Sul, Visiting Professor, KDI School of Public Policy and Management, Former Executive Director, CID, KDI Project Manager Kyoungdoug Kwon, Director, Division of Policy Consultation, CID, KDI 3URMHFW2I¿FHUV Seung Ju Lee, Research Associate, Division of Policy Consultation, CID, KDI Jinha Yoo, Senior Research Associate, Division of Policy Consultation, CID, KDI Lorena Garcia, +ead of the Department for AsiaPaci¿c, AMEXCID Principal Investigator Chong-sup Kim, Professor, Seoul National University Authors Chapter 1. Chong-sup Kim, Professor, Seoul National University Chapter 2. Ji-Chul Ryu, Director, Future Energy Strategy Research Cooperative Chapter 3. Myung Kyoon Lee, Visiting Senior Fellow, Korea Development Institute English Editor IVYFORCE Government Publications Registration Number 11-1051000-000830-01 ISBN 979-11-5932-316-4 94320 ISBN 979-11-5932-302-7 (set) Copyright ؐ 2018 by Ministry of Economy and Finance, Republic of Korea *RYHUQPHQW3XEOLFDWLRQV 5HJLVWUDWLRQ1XPEHU 2017/18 Knowledge Sharing Program with Mexico (II): Local Content Policy and Industrial Development for the Energy Sector Preface Knowledge is a vital ingredient that determines a nation’s economic growth and social development. -

Mexico's Deep Water Success

Energy Alert February 1, 2018 Key Points Round 2.4 exceeded expectations by awarding 18 of 29 (62 percent) of available contract areas Biggest winners were Royal Dutch Shell, with nine contract areas, and PC Carigali, with seven contract areas Investments over $100 billion in Mexico’s energy sector expected in the upcoming years Mexico’s Energy Industry Round 2.4: Mexico’s Deep Water Success On January 31, 2018, the Comisión Nacional de Hidrocarburos (“CNH”) completed the Presentation and Opening of Bid Proposals for the Fourth Tender of Round Two (“Round 2.4”), which was first announced on July 20, 2017. Round 2.4 attracted 29 oil and gas companies from around the world including Royal Dutch Shell, ExxonMobil, Chevron, Pemex, Lukoil, Qatar Petroleum, Mitsui, Repsol, Statoil and Total, among others. Round 2.4 included 60% of all acreage to be offered by Mexico under the current Five Year Plan. Blocks included 29 deep water contract areas (shown in the adjacent map) with an estimated 4.23 billion Barrel of Oil Equivalent (BOE) of crude oil, wet gas and dry gas located in the Perdido Fold Belt Area, Salinas Basin and Mexican Ridges. The blocks were offered under a license contract, similar to the deep water form used by the CNH in Round 1.4. After witnessing the success that companies like ENI, Talos Energy, Inc., Sierra and Premier have had in Mexico over the last several years, Round 2.4 was the biggest opportunity yet for the industry. Some of these deep water contract areas were particularly appealing because they share geological characteristics with some of the projects in the U.S. -

The Future of Pemex: Return to the Rentier-State Model Or Strengthen Energy Resiliency in Mexico?

THE FUTURE OF PEMEX: RETURN TO THE RENTIER-STATE MODEL OR STRENGTHEN ENERGY RESILIENCY IN MEXICO? Isidro Morales, Ph.D. Nonresident Scholar, Center for the United States and Mexico, Baker Institute; Senior Professor and Researcher, Tecnológico de Monterrey March 2020 © 2020 by Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy This material may be quoted or reproduced without prior permission, provided appropriate credit is given to the author and Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy. Wherever feasible, papers are reviewed by outside experts before they are released. However, the research and views expressed in this paper are those of the individual researcher(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Baker Institute. Isidro Morales, Ph.D “The Future of Pemex: Return to the Rentier-State Model or Strengthen Energy Resiliency in Mexico?” https://doi.org/10.25613/y7qc-ga18 The Future of Pemex Introduction Mexico’s 2013-2014 energy reform not only opened all chains of the energy sector to private, national, and international stakeholders, but also set the stage for Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) to possibly become a state productive enterprise. We are barely beginning to discern the fruits and limits of the energy reform, and it will be precisely during Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s administration that these reforms will either be enhanced or curbed. Most analysts who have justified the reforms have highlighted the amount of private investment captured through the nine auctions held so far. Critics of the reform note the drop in crude oil production and the accelerated growth of natural gas imports and oil products.