Oil Refining in Mexico and Prospects for the Energy Reform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate and Energy Benchmark in Oil and Gas Insights Report

Climate and Energy Benchmark in Oil and Gas Insights Report Partners XxxxContents Introduction 3 Five key findings 5 Key finding 1: Staying within 1.5°C means companies must 6 keep oil and gas in the ground Key finding 2: Smoke and mirrors: companies are deflecting 8 attention from their inaction and ineffective climate strategies Key finding 3: Greatest contributors to climate change show 11 limited recognition of emissions responsibility through targets and planning Key finding 4: Empty promises: companies’ capital 12 expenditure in low-carbon technologies not nearly enough Key finding 5:National oil companies: big emissions, 16 little transparency, virtually no accountability Ranking 19 Module Summaries 25 Module 1: Targets 25 Module 2: Material Investment 28 Module 3: Intangible Investment 31 Module 4: Sold Products 32 Module 5: Management 34 Module 6: Supplier Engagement 37 Module 7: Client Engagement 39 Module 8: Policy Engagement 41 Module 9: Business Model 43 CLIMATE AND ENERGY BENCHMARK IN OIL AND GAS - INSIGHTS REPORT 2 Introduction Our world needs a major decarbonisation and energy transformation to WBA’s Climate and Energy Benchmark measures and ranks the world’s prevent the climate crisis we’re facing and meet the Paris Agreement goal 100 most influential oil and gas companies on their low-carbon transition. of limiting global warming to 1.5°C. Without urgent climate action, we will The Oil and Gas Benchmark is the first comprehensive assessment experience more extreme weather events, rising sea levels and immense of companies in the oil and gas sector using the International Energy negative impacts on ecosystems. -

Integrating Into Our Strategy

INTEGRATING CLIMATE INTO OUR STRATEGY • 03 MAY 2017 Integrating Climate Into Our Strategy INTEGRATING CLIMATE INTO OUR STRATEGY • 03 CONTENTS Foreword by Patrick Pouyanné, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, Total 05 Three Questions for Patricia Barbizet, Lead Independent Director of Total 09 _____________ SHAPING TOMORROW’S ENERGY Interview with Fatih Birol, Executive Director of the International Energy Agency 11 The 2°C Objective: Challenges Ahead for Every Form of Energy 12 Carbon Pricing, the Key to Achieving the 2°C Scenario 14 Interview with Erik Solheim, Executive Director of UN Environment 15 Oil and Gas Companies Join Forces 16 Interview with Bill Gates, Breakthrough Energy Ventures 18 _____________ TAKING ACTION TODAY Integrating Climate into Our Strategy 20 An Ambition Consistent with the 2°C Scenario 22 Greenhouse Gas Emissions Down 23% Since 2010 23 Natural Gas, the Key Energy Resource for Fast Climate Action 24 Switching to Natural Gas from Coal for Power Generation 26 Investigating and Strictly Limiting Methane Emissions 27 Providing Affordable Natural Gas 28 CCUS, Critical to Carbon Neutrality 29 A Resilient Portfolio 30 Low-Carbon Businesses to Become the Responsible Energy Major 32 Acquisitions That Exemplify Our Low-Carbon Strategy 33 Accelerating the Solar Energy Transition 34 Affordable, Reliable and Clean Energy 35 Saft, Offering Industrial Solutions to the Climate Change Challenge 36 The La Mède Biorefinery, a Responsible Transformation 37 Energy Efficiency: Optimizing Energy Consumption 38 _____________ FOCUS ON TRANSPORTATION Offering a Balanced Response to New Challenges 40 Our Initiatives 42 ______________ OUR FIGURES 45 04 • INTEGRATING CLIMATE INTO OUR STRATEGY Total at a Glance More than 98,109 4 million employees customers served in our at January 31, 2017 service stations each day after the sale of Atotech A Global Energy Leader No. -

Shell QRA Q2 2021

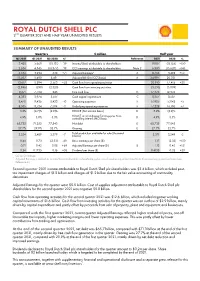

ROYAL DUTCH SHELL PLC 2ND QUARTER 2021 AND HALF YEAR UNAUDITED RESULTS SUMMARY OF UNAUDITED RESULTS Quarters $ million Half year Q2 2021 Q1 2021 Q2 2020 %¹ Reference 2021 2020 % 3,428 5,660 (18,131) -39 Income/(loss) attributable to shareholders 9,087 (18,155) +150 2,634 4,345 (18,377) -39 CCS earnings attributable to shareholders Note 2 6,980 (15,620) +145 5,534 3,234 638 +71 Adjusted Earnings² A 8,768 3,498 +151 13,507 11,490 8,491 Adjusted EBITDA (CCS basis) A 24,997 20,031 12,617 8,294 2,563 +52 Cash flow from operating activities 20,910 17,415 +20 (2,946) (590) (2,320) Cash flow from investing activities (3,535) (5,039) 9,671 7,704 243 Free cash flow G 17,375 12,376 4,383 3,974 3,617 Cash capital expenditure C 8,357 8,587 8,470 9,436 8,423 -10 Operating expenses F 17,905 17,042 +5 8,505 8,724 7,504 -3 Underlying operating expenses F 17,228 16,105 +7 3.2% (4.7)% (2.9)% ROACE (Net income basis) D 3.2% (2.9)% ROACE on an Adjusted Earnings plus Non- 4.9% 3.0% 5.3% controlling interest (NCI) basis D 4.9% 5.3% 65,735 71,252 77,843 Net debt E 65,735 77,843 27.7% 29.9% 32.7% Gearing E 27.7% 32.7% Total production available for sale (thousand 3,254 3,489 3,379 -7 boe/d) 3,371 3,549 -5 0.44 0.73 (2.33) -40 Basic earnings per share ($) 1.17 (2.33) +150 0.71 0.42 0.08 +69 Adjusted Earnings per share ($) B 1.13 0.45 +151 0.24 0.1735 0.16 +38 Dividend per share ($) 0.4135 0.32 +29 1. -

Statoil Business Update

Statoil US Onshore Jefferies Global Energy Conference, November 2014 Torstein Hole, Senior Vice President US Onshore competitively positioned 2013 Eagle Ford Operator 2012 Marcellus Operator Williston Bakken 2011 Stamford Bakken Operator Marcellus 2010 Eagle Ford Austin Eagle Ford Houston 2008 Marcellus 1987 Oil trading, New York Statoil Office Statoil Asset 2 Premium portfolio in core plays Bakken • ~ 275 000 net acres, Light tight oil • Concentrated liquids drilling • Production ~ 55 kboepd Eagle Ford • ~ 60 000 net acres, Liquids rich • Liquids ramp-up • Production ~34 koepd Marcellus • ~ 600 000 net acres, Gas • Production ~130 kboepd 3 Shale revolution: just the end of the beginning • Entering mature phase – companies with sustainable, responsible development approach will be the winners • Statoil is taking long term view. Portfolio robust under current and forecast price assumptions. • Continuous, purposeful improvement is key − Technology/engineering − Constant attention to costs 4 Statoil taking operations to the next level • Ensuring our operating model is fit for Onshore Operations • Doing our part to maintain the company’s capex commitments • Leading the way to reduce flaring in Bakken • Not just reducing costs – increasing free cash flow 5 The application of technology Continuous focus on cost, Fast-track identification, Prioritised development of efficiency and optimisation of development & implementation of potential game-changing operations short-term technology upsides technologies SHORT TERM – MEDIUM – LONG TERM • Stage -

Oil for As Long As Most Americans Can Remember, Gasoline Has Been the Only Fuel They Buy to Fill up the Cars They Drive

Fueling a Clean Transportation Future Chapter 2: Gasoline and Oil For as long as most Americans can remember, gasoline has been the only fuel they buy to fill up the cars they drive. However, hidden from view behind the pump, the sources of gasoline have been changing dramatically. Gasoline is produced from crude oil, and over the last two de- cades the sources of this crude have gotten increasingly di- verse, including materials that are as dissimilar as nail polish remover and window putty. These changes have brought rising global warming emissions, but not from car tailpipes. Indeed, tailpipe emissions per mile are falling as cars get more efficient. Rather, it is the extraction and refining of oil that are getting dirtier over time. The easiest-to-extract sources of oil are dwindling, and the oil industry has increasingly shifted its focus to resources that require more energy-intensive extraction or refining methods, resources that were previously too expensive and risky to be developed. These more challenging oils also result Yeulet © iStock.com/Cathy in higher emissions when used to produce gasoline (Gordon 2012). The most obvious way for the United States to reduce the problems caused by oil use is to steadily reduce oil con- sumption through improved efficiency and by shifting to cleaner fuels. But these strategies will take time to fully im- plement. In the meantime, the vast scale of ongoing oil use Heat-trapping emissions from producing transportation fuels such as gasoline are on the rise, particularly emissions released during extracting and refining means that increases in emissions from extracting and refin- processes that occur out of sight, before we even get in the car. -

Mexico's Deep Water Success

Energy Alert February 1, 2018 Key Points Round 2.4 exceeded expectations by awarding 18 of 29 (62 percent) of available contract areas Biggest winners were Royal Dutch Shell, with nine contract areas, and PC Carigali, with seven contract areas Investments over $100 billion in Mexico’s energy sector expected in the upcoming years Mexico’s Energy Industry Round 2.4: Mexico’s Deep Water Success On January 31, 2018, the Comisión Nacional de Hidrocarburos (“CNH”) completed the Presentation and Opening of Bid Proposals for the Fourth Tender of Round Two (“Round 2.4”), which was first announced on July 20, 2017. Round 2.4 attracted 29 oil and gas companies from around the world including Royal Dutch Shell, ExxonMobil, Chevron, Pemex, Lukoil, Qatar Petroleum, Mitsui, Repsol, Statoil and Total, among others. Round 2.4 included 60% of all acreage to be offered by Mexico under the current Five Year Plan. Blocks included 29 deep water contract areas (shown in the adjacent map) with an estimated 4.23 billion Barrel of Oil Equivalent (BOE) of crude oil, wet gas and dry gas located in the Perdido Fold Belt Area, Salinas Basin and Mexican Ridges. The blocks were offered under a license contract, similar to the deep water form used by the CNH in Round 1.4. After witnessing the success that companies like ENI, Talos Energy, Inc., Sierra and Premier have had in Mexico over the last several years, Round 2.4 was the biggest opportunity yet for the industry. Some of these deep water contract areas were particularly appealing because they share geological characteristics with some of the projects in the U.S. -

The Future of Pemex: Return to the Rentier-State Model Or Strengthen Energy Resiliency in Mexico?

THE FUTURE OF PEMEX: RETURN TO THE RENTIER-STATE MODEL OR STRENGTHEN ENERGY RESILIENCY IN MEXICO? Isidro Morales, Ph.D. Nonresident Scholar, Center for the United States and Mexico, Baker Institute; Senior Professor and Researcher, Tecnológico de Monterrey March 2020 © 2020 by Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy This material may be quoted or reproduced without prior permission, provided appropriate credit is given to the author and Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy. Wherever feasible, papers are reviewed by outside experts before they are released. However, the research and views expressed in this paper are those of the individual researcher(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Baker Institute. Isidro Morales, Ph.D “The Future of Pemex: Return to the Rentier-State Model or Strengthen Energy Resiliency in Mexico?” https://doi.org/10.25613/y7qc-ga18 The Future of Pemex Introduction Mexico’s 2013-2014 energy reform not only opened all chains of the energy sector to private, national, and international stakeholders, but also set the stage for Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) to possibly become a state productive enterprise. We are barely beginning to discern the fruits and limits of the energy reform, and it will be precisely during Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s administration that these reforms will either be enhanced or curbed. Most analysts who have justified the reforms have highlighted the amount of private investment captured through the nine auctions held so far. Critics of the reform note the drop in crude oil production and the accelerated growth of natural gas imports and oil products. -

Mexico in the Time of COVID-19: an OPIS Primer on the Impact of the Virus Over the Country’S Fuel Market

Mexico in the Time of COVID-19: an OPIS Primer on the Impact of the Virus Over the Country’s Fuel Market Your guide to diminishing prices and fuel demand Mexico in the Time of COVID-19 Leading Author Daniel Rodriguez Table of Contents OPIS Contributors Coronavirus Clouds Mexico’s Energy Reform ................................................................1 Justin Schneewind Eric Wieser A Historic Demand Crash ....................................................................................................2 OPIS Editors IHS Markit: Worst Case Drops Mexico’s Gasoline Sales to 1990 levels ...................3 Lisa Street Bridget Hunsucker KCS: Mexico Fuel Demand to Drop Up to 50% .............................................................4 IHS Markit ONEXPO: Retail Sales Drop 60% ......................................................................................4 Contirbuitors Carlos Cardenas ONEXPO: A Retail View on COVID-19 Challenges..........................................................5 Debnil Chowdhury Felipe Perez IHS Markit: USGC Fuel Prices to Remain Depressed Into 2021 .................................6 Kent Williamson Dimensioning the Threat ....................................................................................................7 Paulina Gallardo Pedro Martinez Mexico Maps Timeline for Returning to Normality ......................................................7 OPIS Director, Tales of Two Quarantines ...................................................................................................8 Refined -

Public Procurement Review of Mexico's PEMEX

Public Procurement Review of Mexico’s PEMEX: Adapting to Change in the Oil Industry In an economic environment characterised by historically low oil prices, oil and gas companies such as Petróleos Mexicanos (PEMEX) face tremendous challenges in maintaining and improving their productivity. In a sector where 40 cents of every dollar earned is spent on raw materials and services, procurement systems are central to a company’s competitiveness. Alongside strategies to maximise value creation, procurement frameworks are needed to safeguard the company from mismanagement and corruption. Furthermore, fierce competition among international oil companies requires flexible and agile frameworks to unlock the innovation potential of the market and develop sustainable and strategic alliances. The OECD was invited by PEMEX to review the governance and effectiveness of the recently adopted procurement structure (Procura) in light of good international practices. The reform of PEMEX’s procurement function follows Mexico’s 2013 Energy Reform, which opened up the state-controlled oil and gas sector to competition and changed the objective of PEMEX towards the creation of value. As a result, the company’s procurement function went from a decentralised to a centralised structure to maximise its purchasing power, develop a homogeneous process, facilitate planning, advance the professionalisation of the procurement workforce, and implement a comprehensive supplier management framework. This review assesses the alignment of different, yet complementary, dimensions -

Seadrill Limited

Q1 2020 FLEET STATUS REPORT Seadrill Limited GENERATION / WATER DRILLING RIG NAME BUILT LOCATION CLIENT START EXPIRE DAYRATE US$ COMMENTS TYPE DEPTH (FEET) DEPTH (FEET) Semi-submersibles West Alpha 4th-HE 1986 2,000 23,000 Norway - - - - West Venture 5th-HE 2000 2,600 30,000 Norway - - - - A notice of intent to terminate for convenience has been received from the customer. Norway Neptune Apr-20 Jul-20 267,000 Neptune has indicated that operations are expected to conclude in July-20. Seadrill is entitled to an early termination fee under the contract. West Phoenix 6th-HE 2008 10,000 30,000 Norway Vår Energi Jul-21 Oct-23 359,000 Dayrate partly received in foreign currency. Fluctuations in exchange rates may result in an adjustment to the dayrate. Options Vår Energi Oct-23 Feb-24 359,000 Mobilization fee incremental to dayrate. Dayrate partly received in foreign currency. Fluctuations in exchange rates may result in Norway Equinor May-20 Nov-20 342,500 an adjustment to the dayrate. West Hercules 6th-HE 2008 10,000 35,000 UK Equinor Nov-20 Dec-20 315,000 Norway Equinor Dec-20 Mar-21 275,000 Dayrate partly received in foreign currency. Fluctuations in exchange rates may result in Options Equinor Mar-21 Jun-22 Market indexed rate an adjustment to the dayrate. West Eminence 6th-HE 2009 10,000 30,000 Spain - - - - West Pegasus 6th-HE 2011 10,000 35,000 Norway - - - - West Taurus 6th-BE 2008 10,000 35,000 Norway - - - - Sevan Driller 6th-BE 2009 10,000 40,000 Indonesia - - - - West Orion 6th-BE 2010 10,000 35,000 Malaysia - - - - West Eclipse 6th-BE 2011 10,000 40,000 Namibia - - - - Sevan Brasil 6th-BE 2012 10,000 40,000 Aruba - - - - Sevan Louisiana 6th-BE 2013 10,000 40,000 GoM Walter O&G Mar-20 Jun-20 145,500 Performance bonus incremental to dayrate. -

Public Procurement Review of Mexico's PEMEX

OECD Public Governance Reviews Public Procurement Review of Mexico’s PEMEX ADAPTING TO CHANGE IN THE OIL INDUSTRY This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. FOREWORD – 3 Foreword In an economic environment characterised by historically low oil prices, oil and gas companies such as Petróleos Mexicanos (PEMEX) face tremendous challenges in maintaining and improving their productivity. In a sector where 40 cents of every dollar earned is spent on raw materials and services, procurement systems are central to a company’s competitiveness. Alongside strategies to maximise value creation, procurement frameworks are needed to safeguard the company from mismanagement and corruption. Furthermore, fierce competition among international oil companies requires flexible and agile frameworks to unlock the innovation potential of the market and develop sustainable and strategic alliances. Following an initial evaluation of PEMEX Corporate Governance and Board arrangements in 2010, and taking into account the 2015 OECD Recommendation on Public Procurement, the report Public Procurement Review of Mexico’s PEMEX: Adapting to Change in the Oil Industry reviews progress made by PEMEX in its procurement function since Mexico’s 2013 Energy Reform, which opened up the state- controlled oil and gas sector to competition. As a result, the company’s procurement function went from a decentralised to a centralised structure to maximise its purchasing power, develop a homogeneous process, facilitate planning, advance the professionalisation of the procurement workforce and implement a comprehensive supplier management framework. -

Mexico's Oil and Gas Sector: Background, Reform Efforts

Mexico’s Oil and Gas Sector: Background, Reform Efforts, and Implications for the United States Clare Ribando Seelke, Coordinator Specialist in Latin American Affairs Michael Ratner Specialist in Energy Policy M. Angeles Villarreal Specialist in International Trade and Finance Phillip Brown Specialist in Energy Policy September 28, 2015 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43313 Mexico’s Oil and Gas Sector Summary The future of oil and natural gas production in Mexico is of importance for both Mexico’s economic growth, as well as for U.S. energy security, a key congressional interest. Mexico is a top trade partner and the third-largest crude oil supplier to the United States. Mexico’s state oil company, Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex) remains an important source of government revenue even as it is struggling to counter declining oil production and reserves. Due to an inability to meet rising demand, Mexico has also significantly increased natural gas imports from the United States. Still, gas shortages have hindered the country’s economic performance. On December 20, 2013, Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto signed historic constitutional reforms related to Mexico’s energy sector aimed at reversing oil and gas production declines. On August 11, 2014, secondary laws to implement those reforms officially opened Mexico’s oil, natural gas, and power sectors to private investment. As a result, Pemex can now partner with international companies that have the experience and capital required for exploring Mexico’s vast deep water and shale resources. Leftist parties and others remain opposed to the reforms. The energy reforms transform Pemex into a “productive state enterprise” with more autonomy and a lower tax burden than before, but make it subject to competition with private investors.