Nature. Vol. I, No. 15 February 10, 1870

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No. 40. the System of Lunar Craters, Quadrant Ii Alice P

NO. 40. THE SYSTEM OF LUNAR CRATERS, QUADRANT II by D. W. G. ARTHUR, ALICE P. AGNIERAY, RUTH A. HORVATH ,tl l C.A. WOOD AND C. R. CHAPMAN \_9 (_ /_) March 14, 1964 ABSTRACT The designation, diameter, position, central-peak information, and state of completeness arc listed for each discernible crater in the second lunar quadrant with a diameter exceeding 3.5 km. The catalog contains more than 2,000 items and is illustrated by a map in 11 sections. his Communication is the second part of The However, since we also have suppressed many Greek System of Lunar Craters, which is a catalog in letters used by these authorities, there was need for four parts of all craters recognizable with reasonable some care in the incorporation of new letters to certainty on photographs and having diameters avoid confusion. Accordingly, the Greek letters greater than 3.5 kilometers. Thus it is a continua- added by us are always different from those that tion of Comm. LPL No. 30 of September 1963. The have been suppressed. Observers who wish may use format is the same except for some minor changes the omitted symbols of Blagg and Miiller without to improve clarity and legibility. The information in fear of ambiguity. the text of Comm. LPL No. 30 therefore applies to The photographic coverage of the second quad- this Communication also. rant is by no means uniform in quality, and certain Some of the minor changes mentioned above phases are not well represented. Thus for small cra- have been introduced because of the particular ters in certain longitudes there are no good determi- nature of the second lunar quadrant, most of which nations of the diameters, and our values are little is covered by the dark areas Mare Imbrium and better than rough estimates. -

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

0 Lunar and Planetary Institute Provided by the NASA Astrophysics Data System THORIUM CONCENTRATIONS : IMBRIUM and ADJACENT REGIONS

THORIUM CONCENTRATIONS IN THE IMBRIUM AND ADJACENT REGIONS OF THE MOON. A1 bert E. Metzger, Eldon L. Haines*, Maria I. Etchegaray-Ramirez, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91103, and B. Ray Hawke, Hawaii Institute of Geophysics, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI 96822. The orbital gamma-ray spectrometer deconvolution technique restores some of the inherent spatial resolution and contrast lost because of the substan- tial field of view of the instrument. The technique has previously been applied to the observed Th distributions in the Aristarchus, Apennine, and Smythii regions of the Moon overflown by Apollo (1,2). Application has now been made to the Imbrium region using that portion of the data field extending from 10°W - 42OW, over which the data coverage lies between 18ON and 30°N. The area enclosed not only fills in the interval between the Aristarchus- and Apennine-centered regions previously reported but also provides overlap regions which serve as a test of consistency. It is characterized by basalt flows of various ages, depths, and spectral proper- ties, craters of Copernican and Eratosthenian age, and probable areas of pyroclastic mantling . The Aristarchus and Apennine regions contain two of the three areas of maximum radioactivity observed along the Apollo 15 and 16 data tracks. For both regions the undeconvolved values for the 2' x 2" pixels comprising the data base, range over a factor of 3-4 with maximum values in excess of 8.5 ppm. By comparison, the Imbrium field contains a contrast of only 1.5, the values being more uniformly high, but with an upper limit of about 6.5 ppm. -

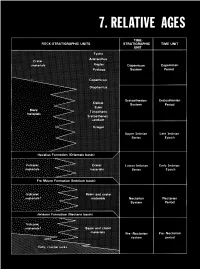

Relative Ages

CONTENTS Page Introduction ...................................................... 123 Stratigraphic nomenclature ........................................ 123 Superpositions ................................................... 125 Mare-crater relations .......................................... 125 Crater-crater relations .......................................... 127 Basin-crater relations .......................................... 127 Mapping conventions .......................................... 127 Crater dating .................................................... 129 General principles ............................................. 129 Size-frequency relations ........................................ 129 Morphology of large craters .................................... 129 Morphology of small craters, by Newell J. Fask .................. 131 D, method .................................................... 133 Summary ........................................................ 133 table 7.1). The first three of these sequences, which are older than INTRODUCTION the visible mare materials, are also dominated internally by the The goals of both terrestrial and lunar stratigraphy are to inte- deposits of basins. The fourth (youngest) sequence consists of mare grate geologic units into a stratigraphic column applicable over the and crater materials. This chapter explains the general methods of whole planet and to calibrate this column with absolute ages. The stratigraphic analysis that are employed in the next six chapters first step in reconstructing -

DMAAC – February 1973

LUNAR TOPOGRAPHIC ORTHOPHOTOMAP (LTO) AND LUNAR ORTHOPHOTMAP (LO) SERIES (Published by DMATC) Lunar Topographic Orthophotmaps and Lunar Orthophotomaps Scale: 1:250,000 Projection: Transverse Mercator Sheet Size: 25.5”x 26.5” The Lunar Topographic Orthophotmaps and Lunar Orthophotomaps Series are the first comprehensive and continuous mapping to be accomplished from Apollo Mission 15-17 mapping photographs. This series is also the first major effort to apply recent advances in orthophotography to lunar mapping. Presently developed maps of this series were designed to support initial lunar scientific investigations primarily employing results of Apollo Mission 15-17 data. Individual maps of this series cover 4 degrees of lunar latitude and 5 degrees of lunar longitude consisting of 1/16 of the area of a 1:1,000,000 scale Lunar Astronautical Chart (LAC) (Section 4.2.1). Their apha-numeric identification (example – LTO38B1) consists of the designator LTO for topographic orthophoto editions or LO for orthophoto editions followed by the LAC number in which they fall, followed by an A, B, C or D designator defining the pertinent LAC quadrant and a 1, 2, 3, or 4 designator defining the specific sub-quadrant actually covered. The following designation (250) identifies the sheets as being at 1:250,000 scale. The LTO editions display 100-meter contours, 50-meter supplemental contours and spot elevations in a red overprint to the base, which is lithographed in black and white. LO editions are identical except that all relief information is omitted and selenographic graticule is restricted to border ticks, presenting an umencumbered view of lunar features imaged by the photographic base. -

Appendix I Lunar and Martian Nomenclature

APPENDIX I LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE A large number of names of craters and other features on the Moon and Mars, were accepted by the IAU General Assemblies X (Moscow, 1958), XI (Berkeley, 1961), XII (Hamburg, 1964), XIV (Brighton, 1970), and XV (Sydney, 1973). The names were suggested by the appropriate IAU Commissions (16 and 17). In particular the Lunar names accepted at the XIVth and XVth General Assemblies were recommended by the 'Working Group on Lunar Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr D. H. Menzel. The Martian names were suggested by the 'Working Group on Martian Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr G. de Vaucouleurs. At the XVth General Assembly a new 'Working Group on Planetary System Nomenclature' was formed (Chairman: Dr P. M. Millman) comprising various Task Groups, one for each particular subject. For further references see: [AU Trans. X, 259-263, 1960; XIB, 236-238, 1962; Xlffi, 203-204, 1966; xnffi, 99-105, 1968; XIVB, 63, 129, 139, 1971; Space Sci. Rev. 12, 136-186, 1971. Because at the recent General Assemblies some small changes, or corrections, were made, the complete list of Lunar and Martian Topographic Features is published here. Table 1 Lunar Craters Abbe 58S,174E Balboa 19N,83W Abbot 6N,55E Baldet 54S, 151W Abel 34S,85E Balmer 20S,70E Abul Wafa 2N,ll7E Banachiewicz 5N,80E Adams 32S,69E Banting 26N,16E Aitken 17S,173E Barbier 248, 158E AI-Biruni 18N,93E Barnard 30S,86E Alden 24S, lllE Barringer 29S,151W Aldrin I.4N,22.1E Bartels 24N,90W Alekhin 68S,131W Becquerei -

Facts & Features Lunar Surface Elevations Six Apollo Lunar

Greek Mythology Quadrants Maria & Related Features Lunar Surface Elevations Facts & Features Selene is the Moon and 12 234 the goddess of the Moon, 32 Diameter: 2,160 miles which is 27.3% of Earth’s equatorial diameter of 7,926 miles 260 Lacus daughter of the titans 71 13 113 Mare Frigoris Mare Humboldtianum Volume: 2.03% of Earth’s volume; 49 Moons would fit inside Earth 51 103 Mortis Hyperion and Theia. Her 282 44 II I Sinus Iridum 167 125 321 Lacus Somniorum Near Side Mass: 1.62 x 1023 pounds; 1.23% of Earth’s mass sister Eos is the goddess 329 18 299 Sinus Roris Surface Area: 7.4% of Earth’s surface area of dawn and her brother 173 Mare Imbrium Mare Serenitatis 85 279 133 3 3 3 Helios is the Sun. Selene 291 Palus Mare Crisium Average Density: 3.34 gm/cm (water is 1.00 gm/cm ). Earth’s density is 5.52 gm/cm 55 270 112 is often pictured with a 156 Putredinis Color-coded elevation maps Gravity: 0.165 times the gravity of Earth 224 22 237 III IV cresent Moon on her head. 126 Mare Marginis of the Moon. The difference in 41 Mare Undarum Escape Velocity: 1.5 miles/sec; 5,369 miles/hour Selenology, the modern-day 229 Oceanus elevation from the lowest to 62 162 25 Procellarum Mare Smythii Distances from Earth (measured from the centers of both bodies): Average: 238,856 term used for the study 310 116 223 the highest point is 11 miles. -

Baylor University Commencement May Seventh and Eighth, Two Thousand Twenty-One

B AYLOR U NIVERSITY C OMMEN C EMENT May Seventh and Eighth, Two Thousand Twenty-one McLane Stadium . Waco, Texas Baylor University Commencement May Seventh and Eighth, Two Thousand Twenty-one Table of Contents 2 Program for Friday Morning The School of Engineering and Computer Science The School of Education The College of Arts & Sciences The Graduate School 3 List of Degrees Presented in Friday Morning Ceremony 8 Program for Friday Afternoon The School of Music The College of Arts & Sciences The Graduate School 9 List of Degrees Presented in Friday Afternoon Ceremony 14 Program for Saturday Morning The Robbins College of Health and Human Sciences The Diana R. Garland School of Social Work The Louise Herrington School of Nursing The Graduate School 15 List of Degrees Presented in Saturday Morning Ceremony 20 Program for Saturday Afternoon The Hankamer School of Business The Graduate School 21 List of Degrees Presented in Saturday Afternoon Ceremony 26 Commencement Traditions A History of Baylor Commencement Academic Regalia The Diploma Graduating with Latin Honors Baylor Interdisciplinary Core Official Baylor Ring Senior Class Gift 28 Faculty Ushers for Commencement Faculty Marshals for Commencement Ceremony Musicians 29 General Information The National Anthem Back Cover “That Good Old Baylor Line” 1 The School of Engineering and Computer Science, The School of Education, The College of Arts & Sciences, and The Graduate School Friday, May 7, 2021, Nine o’clock in the Morning – McLane Stadium Prelude Presentation of Degree Candidates Ceremonial Piece on CWM Rhondda by William Mac Davis President Livingstone The Earle of Oxford’s March by William Byrd, arranged by Assisted by Dr. -

1 Region 1 – Western US

^ = Partial Bathymetric Coverage ! = New to/updated in 2011 blue = Vision Coverage * = Detailed Shoreline Only Region 1 – Western US Lake Name State County French Meadows Reservoir CA Placer Alamo Lake AZ La Paz Goose Lake CA Modoc * Bartlett Reservoir AZ Maricopa Harry L Englebright Lake CA Yuba Blue Ridge Reservoir AZ Coconino Hell Hole Reservoir CA Placer Horseshoe Reservoir AZ Yavapai Hensley Lake CA Madera Lake Havasu AZ/CA Various * Huntington Lake CA Fresno Lake Mohave AZ/NV Various Ice House Reservoir CA El Dorado Lake Pleasant AZ Yavapai/Maricopa Indian Valley Reservoir CA Lake Lower Lake Mary AZ Coconino * Jackson Meadow Reservoir CA Sierra San Carlos Reservoir AZ Various * Jenkinson Lake CA El Dorado Sunrise Lake AZ Apache Lake Almanor CA Plumas * Theodore Roosevelt Lake AZ Gila Lake Berryessa CA Napa Upper Lake Mary AZ Coconino Lake Britton CA Shasta Antelop Valley Reservoir CA Plumas ^ Lake Cachuma CA Santa Barbara Barrett Lake CA San Deigo Lake Casitas CA Ventura Beardsley Lake CA Tuolumne Lake Del Valle CA Alameda Black Butte Lake CA Glenn Lake Isabella CA Kern Briones Reservoir CA Contra Costa Lake Jennings CA San Deigo Bullards Bar Reservoir CA Yuba Lake Kaweah CA Tulare Camanche Reservoir CA Various Lake McClure CA Mariposa Caples Lake CA Alpine Lake Natoma CA Sacramento Castaic Lake CA Los Angeles Lake of the Pines CA Nevada Castle Lake CA Siskiyou Lake Oroville CA Butte ^ Clear Lake CA Lake Lake Piru CA Ventura ^ Clear Lake Reservoir CA Modoc * Lake Shasta CA Shasta Cogswell Reservoir CA Los Angeles Lake Sonoma CA -

Beware of the 'Siren Call' to Lunar Polar Water Ice!

Beware of the ‘siren call’ to lunar polar water ice! INGREDIENTS: Water, Hydrogen Sulfide, Ammonia, Sulfur Dioxide, Ethylene, Carbon Dioxide, Methanol, Methane, Hydroxide PSR water ice (“∼3.5% of cold traps exhibit ice exposures”, Li et al., 2018) What lies below 1 m??? (i.e., Siegler et al., 2016, ice stability depths) Geotechnical properties??? Hayne, et al. 2015 Fisher, et al. 2017 Sanin, et al. 2017 Resources Galore! Pyroclastic Glass Titanium KREEP Start simple: FeTiO3+H2 ---->Fe+TiO2+H2O Modeled A Scientific Bonanza! Mare Ages Lunar Science for Landed Missions Workshop Findings Report https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2018EA000490 Marius Pit Reiner Gamma Marius Hills Wanted Lunar Outpost at Aristarchus based on 1:5M USGS Plateau geological maps and Single lunar field-station Wilhelms, 1987 looking for a long-term Within 100 km relationship with a Herodotus, Aristarchus craters, Aristarchus dependable, trustworthy Plateau (lavas and ash), Vallis Schröteri power generation unit. Within 250 km Prinz, Krieger, Wollaston craters, Montes Nuclear doesn’t scare me. Harbinger, Montes Agricola, Prinz rilles, [email protected] Oceanus Procellarum Within 500 km Marius, Brayley, Diophantus, Delisle, Angstrom, Gruithusien, Schiaparelli, craters, Marius Hills, Rima Marius, Gruithusien domes, late Imbrium lava flows Within 750 km Kepler, Euler, Mairan, Sharp, Lavoisier A, Lichtenberg, Briggs, Seleucus, Russell, Struve, Be careful of the allure Eddington, Galilaei, Reiner craters, Reiner Gamma swirls, Rümker Plateau, Mare 250 km to ‘perpetual sunlight’! Imbrium, young lavas near Lichtenberg Within 1000 km 500 km Cavalerius, Hevelius, Encke, Hortensius, Copernicus, Pytheas, Lambert, Bianchini, Bouguer, Harpalus, Markov, Harding, Krafft, 750 km Cardanus craters, Sinus Iridium, Sinus Roris, Montes Jura, Montes Carpatus, Flamsteed ring mare, Hortensius domes, feldspathic 1000 km highlands. -

The Thickness of Mare Basalts in Imbrium Basin Estimated from Penetrating Craters

40th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2009) 1727.pdf THE THICKNESS OF MARE BASALTS IN IMBRIUM BASIN ESTIMATED FROM PENETRATING CRATERS. B. J. Thomson1, E. B. Grosfils2, D. B. J. Bussey1, and P. D. Spudis3; 1The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, 11100 Johns Hopkins Blvd., Laurel, MD 20723 (bradley.thomson @ jhuapl.edu); 2Pomona College, 185 E 6th St., Claremont, CA 91711; 3Lunar and Planetary Institute, 3600 Bay Area Blvd., Hous- ton TX 77058. Introduction: Approximately 16% (6×106 km2) of Method: To estimate basalt thickness using craters the Moon’s surface is covered by basaltic lava flows that have penetrated through the mare, we use compo- [1], and although the total areal extent of these flows is sitional data derived from Clementine UV-VIS images easily determined, their thicknesses are more difficult to identify and quantify the signature of basement to constrain. The total volume of lunar lava provides highland materials in their ejecta. First, Clementine basic constraints on the Moon’s thermal and petroge- UV-VIS data are processed to derive maps of the esti- netic evolution. Previously, thickess estimates have mated iron (FeO) weight percent of the craters of inter- been obtained from gravity, seismic, and radar data est [12]. Crater morphometric and topographic data [e.g., 2-4]; measurements of impact craters partially are then used to determine the maximum excavation filled with basalt [5,6]; comparisons of lunar basins depth using a geometric scaling model [e.g., 13]. Fi- filled with mare deposits to unfilled basins [7]; and nally, we use the iron compositional maps to determine spectral analysis of impact craters that have completely the radius of the low FeO basement material emplaced penetrated the mare [8-10]. -

Lunar Topographical Studies Section Banded Craters Program

Lunar Topographical Studies Section Banded Craters Program These highly stylized drawings are intended only to give a general impression of each Group In the March 1955 Journal of the British Astronomical Association, K. W. Abineri and A. P. Lenham published a paper in which they suggested that banded craters could be grouped into the following five categories: Group 1 - (Aristarchus type) Craters are very bright, quite small, and have fairly small dark floors leaving broad bright walls. The bands, on the whole, apparently radiate from near the centre of the craters. These craters are often the centres of simple bright ray systems. Group 2 - (Conon type) Rather dull craters with large dark floors and narrow walls. Very short bands show on the walls but cannot be traced on the floors. The bands, despite their shortness, appear radial to the crater centre. Group 3 - (Messier type) A broad east-west band is the main feature of the floors. Group 4 - (Birt type) Long, usually curved, bands radiate from a non-central dull area. The brightness and size are similar to the Group 1 craters. Group 5 - (Agatharchides A type) One half of the floor is dull and the bands radiate from near the wall inside this dull section and are visible on the dull and bright parts of the floor. 1 BANDED CRATERS BY NAMED FEATURE NAMED FEATURE LUNAR LONG. LUNAR LAT. GROUP (Unnamed Feature) E0.9 S18.0 1 (Unnamed Feature) E4.8 N23.4 4 (Unnamed Feature) W45.4 S23.6 3 (Unnamed Feature) E56.6 N38.3 1 Abbot (Apollonius K) E54.8 N5.6 1 Abenezra A (Mayfair A) E10.5 22.8S 2