Annie Dillard: at the Altar of Nature Kelley A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Web-Book Catalog 2021-05-10

Lehigh Gap Nature Center Library Book Catalog Title Year Author(s) Publisher Keywords Keywords Catalog No. National Geographic, Washington, 100 best pictures. 2001 National Geogrpahic. Photographs. 779 DC Miller, Jeffrey C., and Daniel H. 100 butterflies and moths : portraits from Belknap Press of Harvard University Butterflies - Costa 2007 Janzen, and Winifred Moths - Costa Rica 595.789097286 th tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA rica Hallwachs. Miller, Jeffery C., and Daniel H. 100 caterpillars : portraits from the Belknap Press of Harvard University Caterpillars - Costa 2006 Janzen, and Winifred 595.781 tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA Rica Hallwachs 100 plants to feed the bees : provide a 2016 Lee-Mader, Eric, et al. Storey Publishing, North Adams, MA Bees. Pollination 635.9676 healthy habitat to help pollinators thrive Klots, Alexander B., and Elsie 1001 answers to questions about insects 1961 Grosset & Dunlap, New York, NY Insects 595.7 B. Klots Cruickshank, Allan D., and Dodd, Mead, and Company, New 1001 questions answered about birds 1958 Birds 598 Helen Cruickshank York, NY Currie, Philip J. and Eva B. 101 Questions About Dinosaurs 1996 Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, NY Reptiles Dinosaurs 567.91 Koppelhus Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, N. 101 Questions About the Seashore 1997 Barlowe, Sy Seashore 577.51 Y. Gardening to attract 101 ways to help birds 2006 Erickson, Laura. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA Birds - Conservation. 639.978 birds. Sharpe, Grant, and Wenonah University of Wisconsin Press, 101 wildflowers of Arcadia National Park 1963 581.769909741 Sharpe Madison, WI 1300 real and fanciful animals : from Animals, Mythical in 1998 Merian, Matthaus Dover Publications, Mineola, NY Animals in art 769.432 seventeenth-century engravings. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. Adam Ant=English musician who gained popularity as the Amy Adams=Actress, singer=134,576=68 AA lead singer of New Wave/post-punk group Adam and the Amy Acuff=Athletics (sport) competitor=34,965=270 Ants=70,455=40 Allison Adler=Television producer=151,413=58 Aljur Abrenica=Actor, singer, guitarist=65,045=46 Anouk Aimée=Actress=36,527=261 Atif Aslam=Pakistani pop singer and film actor=35,066=80 Azra Akin=Model and actress=67,136=143 Andre Agassi=American tennis player=26,880=103 Asa Akira=Pornographic act ress=66,356=144 Anthony Andrews=Actor=10,472=233 Aleisha Allen=American actress=55,110=171 Aaron Ashmore=Actor=10,483=232 Absolutely Amber=American, Model=32,149=287 Armand Assante=Actor=14,175=170 Alessandra Ambrosio=Brazilian model=447,340=15 Alan Autry=American, Actor=26,187=104 Alexis Amore=American pornographic actress=42,795=228 Andrea Anders=American, Actress=61,421=155 Alison Angel=American, Pornstar=642,060=6 COMPLETEandLEFT Aracely Arámbula=Mexican, Actress=73,760=136 Anne Archer=Film, television actress=50,785=182 AA,Abigail Adams AA,Adam Arkin Asia Argento=Actress, film director=85,193=110 AA,Alan Alda Alison Armitage=English, Swimming=31,118=299 AA,Alan Arkin Ariadne Artiles=Spanish, Model=31,652=291 AA,Alan Autry Anara Atanes=English, Model=55,112=170 AA,Alvin Ailey ……………. AA,Amedeo Avogadro ACTION ACTION AA,Amy Adams AA,Andre Agasi ALY & AJ AA,Andre Agassi ANDREW ALLEN AA,Anouk Aimée ANGELA AMMONS AA,Ansel Adams ASAF AVIDAN AA,Army Archerd ASKING ALEXANDRIA AA,Art Alexakis AA,Arthur Ashe ATTACK ATTACK! AA,Ashley -

Linda Hogan and Annie Dillard Bachelor’S Diploma Thesis

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Markéta Tomášková Searching for Home on This Earth: Linda Hogan and Annie Dillard Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Martina Horáková, Ph. D. 2016 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature - 2 - Acknowledgement I am very grateful to my supervisor Dr. Martina Horáková for her guidance, kind support, and valuable comments on the manuscript. I would also like to thank my family, including Riki the dog, for providing me with a cosy and warm dwelling, which made the writing and the completion of this paper possible. - 3 - Searching for Home on This Earth: Linda Hogan and Annie Dillard Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................- 5 - 1 The Perception of ‘Objects’ ............................................................................................- 9 - 1.1 ‘Objects’ in Dwellings ............................................................................................. - 14 - 1.2 ‘Objects’ in Pilgrim at Tinker Creek ....................................................................... - 18 - 2 The Perception of Animals ..............................................................................................- 24 - 2.1 Animals in Dwellings ............................................................................................. -

LIT 202 American Literature II

College of San Mateo Official Course Outline 1. COURSE ID: LIT. 202 TITLE: American Literature II C-ID: ENGL 135 Units: 3.0 units Hours/Semester: 48.0-54.0 Lecture hours Method of Grading: Letter Grade Only Prerequisite: Eligibility for ENGL 100 or ENGL 105 2. COURSE DESIGNATION: Degree Credit Transfer credit: CSU; UC AA/AS Degree Requirements: CSM - GENERAL EDUCATION REQUIREMENTS: E2b. English, literature, Speech Communication CSM - GENERAL EDUCATION REQUIREMENTS: E2c.Communication and Analytical Thinking CSM - GENERAL EDUCATION REQUIREMENTS: E5c. Humanities CSU GE: CSU GE Area C: ARTS AND HUMANITIES: C2 - Humanities (Literature, Philosophy, Languages Other than English) IGETC: IGETC Area 3: ARTS AND HUMANITIES: B: Humanities 3. COURSE DESCRIPTIONS: Catalog Description: Study of American Literature from the end of the U. S. Civil War in 1865 through the modern day. Lectures, discussions, and recorded readings. 4. STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOME(S) (SLO'S): Upon successful completion of this course, a student will meet the following outcomes: 1. Demonstrate familiarity with a variety of representative works of American literature from the 1870s to the present, identifying major literary, cultural, and historical themes. 2. Present a critical, independent analysis of themes in one or more works of American literature from the 1870s to the present in the form of a project, paper, or presentation. 5. SPECIFIC INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES: Upon successful completion of this course, a student will be able to: 1. Demonstrate an understanding of the contexts- historical, intellectual, social, and cultural-of a broad range of American literature from the 1870s to the present. 2. Identify major literary figures and their works in the period. -

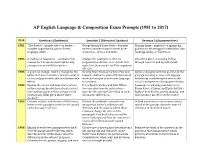

AP English Language & Composition Exam Prompts (1981 to 2017)

AP English Language & Composition Exam Prompts (1981 to 2017) YEAR Question 1 (Synthesis) Question 2 (Rhetorical Analysis) Question 3 (Argumentative) 1981 “The Rattler”- analyze effect on reader – George Bernard Shaw letter – describe Thomas Szasz – argue for or against his consider organization, point of view, writer’s attitude toward mother & her position on the struggle for definition. Use language, detail. cremation – diction and detail readings, study, or experience. 1982 A reading on happiness – summarize his Analyze the strategies or devices Describe a place, conveying feeling reasons for his opinion and explain why (organization, diction, tone, detail) that through concrete and specific detail. you agree or not with his opinion make Gov. Stevenson’s Cat Veto argument effective. 1983 A quote on change - Select a change for the Excerpt from Thomas Carlyle’s Past and Agree or disagree with the position in the better that has occurred or that you want to Present – define Carlyle’s attitude toward passage on living in an era of language occur; analyze its desirable and undesirable work and analyze how he uses language inflation by considering the ethical and effects to convince…. social consequences of language inflation. 1984 Explain the nature and importance of two Percy Bysshe Shelley and John Milton – A passage on a boxing match between or three means by which you keep track of two very short quotes on freedom – Benny Paret, a Cuban, and Emile Griffith – time and discuss how these means reveal describe the concept of freedom in each; Analyze how diction, syntax, imagery, and your person. (Hint given about “inner discuss the differences. -

Let's Talk About It at Davie County Public Library

Let’s Talk About It at Davie County Public Library Davie County Public Library has enjoyed a long history of Let’s Talk About It programming. Below is a listing of LTAI themes and books that we have explored over the years. 2015: Too Hot to Handle? Revisiting Literary Classics (originated by Davie County Public Library) To Kill a Mockingbird The Great Gatsby Of Mice and Men Catcher in the Rye 1984 2014: Muslim Journeys – American Stories Prince Among Slaves The Columbia Sourcebook Acts of Faith A Quiet Revolution The Butterfly Mosque 2013: Divergent Cultures – the Middle East in Literature Reading Lolita in Tehran Palace Walk A Perfect Peace Three Cups of Tea Nine Parts of Desire 2012: Making Sense of the Civil War March by Geraldine Brooks Crossroads of Freedom: Antietam by James McPherson America's War, a new anthology of historical fiction, diaries, memoirs, and short stories, ed. Edward L. Ayers. 2011: Altered Landscapes: North Carolina's Changing World Salt: A Novel by Isabel Zuber Garden Spells by Sarah Addison Allen If You Want Me To Stay by Michael Parker Blood Done Sign My Name: A True Story by Timothy Tyson Plant Life: A Novel by Pamela Duncan 2010: Law and Literature: The Eva R. Rubin Series Billy Budd & Other Stories by Herman Melville The Tragedy of Pudd'nhead Wilson by Mark Twain A Lesson Before Dying by Ernest Gaines Snow Falling on Cedars by David Guterson The Emperor of Ocean Park by Stephen Carter 1 2009: Discovering the Literary South: The Louis D. Rubin, Jr. Series Gap Creek: The Story of a Marriage by Robert Morgan A Virtuous Woman by Kaye Gibbons The Jew Store by Stella Suberman Clover by Dori Sanders The Coal Tattoo: A Novel by Silas House 2008: Family: the Way We Were, the Way We Are This House of Sky by Ivan Doig Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry and The Glass Menagerie by Tennessee Williams Ordinary People by Judith Guest Points of View: an Anthology of Short Stories ed. -

The Poetics and Politics of Liminality: New Transcendentalism in Contemporary American Women’S Writing

The Poetics and Politics of Liminality: New Transcendentalism in Contemporary American Women’s Writing by Teresa O’Rourke A Doctoral Thesis Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy of Loughborough University 21st June 2017 © by Teresa O’Rourke 2017 ABSTRACT By setting the writings of Etel Adnan, Annie Dillard, Marilynne Robinson and Rebecca Solnit into dialogue with those of the New England Transcendentalists, this thesis proposes a New Transcendentalism that both reinvigorates and reimagines Transcendentalist thought for our increasingly intersectional and deterritorialized contemporary context. Drawing on key re-readings by Stanley Cavell, George Kateb and Branka Arsić, the project contributes towards the twenty-first-century shift in Transcendentalist scholarship which seeks to challenge the popular image of New England Transcendentalism as uncompromisingly individualist, abstract and ultimately the preserve of white male privilege. Moreover, in its identification and examination of an interrelated poetics and politics of liminality across these old and new Transcendentalist writings, the project also extends the scope of a more recent strain of Transcendentalist scholarship which emphasises the dialogical underpinnings of the nineteenth-century movement. The project comprises three central chapters, each of which situates New Transcendentalism within a series of vertical and lateral dialogues. The trajectory of my chapters follows the logic of Emerson’s ‘ever-widening circles’, in that each takes a wider critical lens through which to explore the dialogical relationship between my four writers and the New England Transcendentalists. In Chapter 1 the focus is upon anthropological theories of liminality; in Chapter 2 upon feminist interventions within psychoanalysis; and in Chapter 3 upon the revisionary work of Post-West criticism. -

Rhetorical Strategies: Any Device Used to Analyze the Interplay Between a Writer/Speaker, a Specific Audience, and a Particular Purpose

RHETORICAL STRATEGIES: ANY DEVICE USED TO ANALYZE THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN A WRITER/SPEAKER, A SPECIFIC AUDIENCE, AND A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. 1. Abstract diction: (compare to concrete diction) Abstract diction refers to words that describe concepts rather than concrete images (ideas and qualities rather than observable or specific things, people, or places.) These words do not appeal imaginatively to the reader's senses. Abstract words create no "mental picture" or any other imagined sensations for readers. Abstract words include: Love, Hate, Feelings, Emotions, Temptation, Peace, Seclusion, Alienation, Politics, Rights, Freedom, Intelligence, Attitudes, Progress, Guilt, etc. Try to create a mental picture of "love." Do you picture a couple holding hands, a child hugging a mother, roses and valentines? These are not "love." Instead, they are concrete objects you associate with love. Because it is an abstraction, the word "love" itself does not imaginatively appeal to the reader's senses. "Ralph and Jane have experienced difficulties in their lives, and both have developed bad attitudes because of these difficulties. They have now set goals to surmount these problems, although the unfortunate consequences of their experiences are still apparent in many everyday situations." 2. Absolutes: an adverbial clause that has a nonfinite verb or no verb at all (the clause is missing “was” or “were” or it is replaced by a verbal, making it dependent). The prisoners marched past, their hands above their heads. (The prisoners marched past. Their hands were above their heads.) The work having been finished, the gardener came to ask for payment. (The work was finished. The gardener came to ask for payment.) “But I knew her sick from the disease that would not go, her legs bunched under the yellow sheets, the bones gone limp as worms.”—Sandra Cisneros, The House on Mango Street “We pretended with our heads thrown back, our arms limp and useless, dangling like the dead.”—Sandra Cisneros, The House on Mango Street 3. -

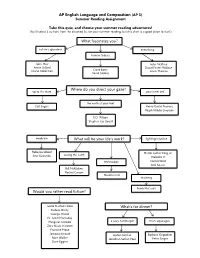

AP English Language and Composition (AP 3) What Fascinates

AP English Language and Composition (AP 3) Summer Reading Assignment Take this quiz, and choose your summer reading adventures! (You’ll select 3 authors from the attached list for your summer reading, but this chart is a good place to start.) What fascinates you? nature’s grandeur everything human foibles John Muir John McPhee Annie Dillard David Foster Wallace Diane Ackerman Dave Barry Lewis Thomas David Sedaris Where do you direct your gaze? up to the stars your inner self the earth at your feet Carl Sagan Henry David Thoreau Ralph Waldo Emerson E.O. Wilson Stephen Jay Gould medicine What will be your life’s work? fighting injustice Rebecca Skloot Martin Luther King, Jr. Atul Gawande saving the earth Malcolm X technology Cornel West bell hooks Bill McKibben Rachel Carson Nicolas Carr teaching Frank McCourt Would you rather read fiction? Leslie Marmon Silko What’s for dinner? Eudora Welty George Orwell N. Scott Momaday a juicy hamburger fresh asparagus Margaret Atwood Zora Neale Hurston Francine Prose Jamaica Kincaid Upton Sinclair Barbara Kingsolver Alice Walker Jonathan Safran Foer Peter Singer Dave Eggers Select three authors from the list below. Read at least one work by each. At least one of the works you select should be a longer, book-length work. A collection of essays counts as a longer work. The other works you select may be individual essays or speeches. The AP English Language and Composition course is primarily a nonfiction class that focuses on how and why an author says what he says. The authors on this list have been identified by the College Board as authors who skillfully employ language to achieve a specific purpose with a specific audience in mind. -

Western Sierra Collegiate Academy

2014–2015 Literature RESOURCE GUIDE Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, Nature Writing, and Environmental Literature The vision of the United States Academic Decathlon® is to provide students the opportunity to excel academically through team competition. Western Sierra Collegiate Academy - Rocklin, CA Toll Free: 866-511-USAD (8723) • Direct: 712-366-3700 • Fax: 712-366-3701 • Email: [email protected] • Website: www.usad.org This material may not be reproduced or transmitted, in whole or in part, by any means, including but not limited to photocopy, print, electronic, or internet display (public or private sites) or downloading, without prior written permission from USAD. Violators may be prosecuted. Copyright © 2014 by United States Academic Decathlon®. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Style and Technique ......................... 28 SECTION I: Critical Reading ......................... 4 Chapter One: “Heaven and Earth in Jest”. .29 Chapter Two: “Seeing” ...................... 32 SECTION II: Nature Writing, Environmental Literature, Chapter Three: “Winter” ..................... 33 and Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek ..... 10 Chapter Four: “The Fixed” ................... 35 Introduction ............................... 10 Chapter Five: “Untying the Knot” ............. 36 The Natural History Essay Chapter Six: “The Present”. .37 and the Romantic Movement ................. 11 Chapter Seven: “Spring” .................... 38 Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Nature ............... 11 Chapter Eight: “Intricacy” .................... 39 Henry -

The Writing Life by Annie Dillard

NATIONAL B E S T S E L L E R AUTOBIOGRAPHY The Critics Praise The Writing Lifi "Annie Dillard is a wonderful writer, "A kind of spiritual Strunk & White, a small and brillinnt uid ·boo lo dw .ual THE WRITING LIFE is full of joys." landscape of a writer's task.... Dillard brings the same pa ssion nnd t' OI IIIt'<' • - NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW tive intelligence to this narrative as she has to her other w rk. " - /J o1 /011 U/olw "For nonwriters, it is a glimpse into the trials and satisfactions o · , lift· , pt' lll with words. For writers, it is a warm, rambling conversation with :1 stimlll11 1ing and extraordinarily talented colleague." - hi ago 'lribtlilr "Her book is ... scattered with pearls. Each reader will be attra t d lo dill!· r· ent bright parts .. Gracefully and simply told, these little stori ·s ill um in.1tr the writi:1.g life .. Her advice to writers is encouraging and invigorn1·ing. '' -Cleveland P!ttill I ,.,tf,•r "The Writing Life is a spare volume ... that has the power and force o a d L<l· nating bomb. A book bursting with metaphors and prose bristlin with incident." - Detroit N1'''' "We may fairly ask that a book about writing be, itself, a work of art. An I that is what Dillard offers .... Anyone hoping to see inside the process of lir erary artistry is unlikely to find a more lucid, sensitive or poetic view." -Philadelphia Inquirer "The Writing Life is as f,lim and potent as the Tao Te Ching, that ancient hi nese manual on the art of living ... -

Contents 2020-2021

Contents 2020-2021 About Hollins University 1 Mission 1 Graduate Programs 2 Graduate Facilities 2 Academic Support Programs 2 Admission Guidelines 5 Readmission to Hollins 7 Tuition and Fees 7 Financial Assistance 8 Federal Title IV Financial Aid 9 Academic Regulations 10 Auditing 10 Adding/Dropping courses 10 Class Attendance 10 Grades 11 Honor Code 11 Incompletes 11 Transfer Credit 12 Withdrawals 12 Business Office Policies 12 Housing 14 Tuition Fee/Refund Policies 14 Policy on Return of Unearned TA Funds to the DOD 15 Notification of Rights under FERPA 15 Children’s Literature (M.A. /M.F.A.) 17 Courses 18 Faculty 21 Children’s Book Writing and Illustrating (M.F.A.) 24 Courses 25 Faculty 27 Certificate in Children’s Book Illustration 31 Courses 32 Faculty 33 Creative Writing (M.F.A.) 34 Courses 35 Faculty 38 Dance (M.F.A.) 40 Courses 41 Faculty 45 Master of Arts in Liberal Studies (M.A.L.S.) 49 Certificate of Advanced Studies (C.A.S.) 51 Courses 51 Faculty 65 Medical Communication Certificate 68 Courses 68 Faculty 70 Playwriting (M.F.A.) 71 Concentrations 72 Courses 74 Faculty 78 Certificate in New Play Directing 80 Courses 81 Faculty 82 Certificate in New Play Performance 83 i Courses 84 Faculty 85 Screenwriting and Film Studies (M.A. /M.F.A.) 86 Courses 87 Faculty 88 Master of Arts in Teaching (M.A.T.) 91 Courses 92 Faculty 94 Master of Arts in Teaching and Learning (M.A.T.L.) 95 Courses 95 Faculty 96 Administration 97 Graduate Center Staff 98 Telephone Numbers 99 University Calendar 100 ii About Hollins Hollins was founded in 1842 as Virginia’s first chartered women’s college.