Western Sierra Collegiate Academy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Web-Book Catalog 2021-05-10

Lehigh Gap Nature Center Library Book Catalog Title Year Author(s) Publisher Keywords Keywords Catalog No. National Geographic, Washington, 100 best pictures. 2001 National Geogrpahic. Photographs. 779 DC Miller, Jeffrey C., and Daniel H. 100 butterflies and moths : portraits from Belknap Press of Harvard University Butterflies - Costa 2007 Janzen, and Winifred Moths - Costa Rica 595.789097286 th tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA rica Hallwachs. Miller, Jeffery C., and Daniel H. 100 caterpillars : portraits from the Belknap Press of Harvard University Caterpillars - Costa 2006 Janzen, and Winifred 595.781 tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA Rica Hallwachs 100 plants to feed the bees : provide a 2016 Lee-Mader, Eric, et al. Storey Publishing, North Adams, MA Bees. Pollination 635.9676 healthy habitat to help pollinators thrive Klots, Alexander B., and Elsie 1001 answers to questions about insects 1961 Grosset & Dunlap, New York, NY Insects 595.7 B. Klots Cruickshank, Allan D., and Dodd, Mead, and Company, New 1001 questions answered about birds 1958 Birds 598 Helen Cruickshank York, NY Currie, Philip J. and Eva B. 101 Questions About Dinosaurs 1996 Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, NY Reptiles Dinosaurs 567.91 Koppelhus Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, N. 101 Questions About the Seashore 1997 Barlowe, Sy Seashore 577.51 Y. Gardening to attract 101 ways to help birds 2006 Erickson, Laura. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA Birds - Conservation. 639.978 birds. Sharpe, Grant, and Wenonah University of Wisconsin Press, 101 wildflowers of Arcadia National Park 1963 581.769909741 Sharpe Madison, WI 1300 real and fanciful animals : from Animals, Mythical in 1998 Merian, Matthaus Dover Publications, Mineola, NY Animals in art 769.432 seventeenth-century engravings. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. Adam Ant=English musician who gained popularity as the Amy Adams=Actress, singer=134,576=68 AA lead singer of New Wave/post-punk group Adam and the Amy Acuff=Athletics (sport) competitor=34,965=270 Ants=70,455=40 Allison Adler=Television producer=151,413=58 Aljur Abrenica=Actor, singer, guitarist=65,045=46 Anouk Aimée=Actress=36,527=261 Atif Aslam=Pakistani pop singer and film actor=35,066=80 Azra Akin=Model and actress=67,136=143 Andre Agassi=American tennis player=26,880=103 Asa Akira=Pornographic act ress=66,356=144 Anthony Andrews=Actor=10,472=233 Aleisha Allen=American actress=55,110=171 Aaron Ashmore=Actor=10,483=232 Absolutely Amber=American, Model=32,149=287 Armand Assante=Actor=14,175=170 Alessandra Ambrosio=Brazilian model=447,340=15 Alan Autry=American, Actor=26,187=104 Alexis Amore=American pornographic actress=42,795=228 Andrea Anders=American, Actress=61,421=155 Alison Angel=American, Pornstar=642,060=6 COMPLETEandLEFT Aracely Arámbula=Mexican, Actress=73,760=136 Anne Archer=Film, television actress=50,785=182 AA,Abigail Adams AA,Adam Arkin Asia Argento=Actress, film director=85,193=110 AA,Alan Alda Alison Armitage=English, Swimming=31,118=299 AA,Alan Arkin Ariadne Artiles=Spanish, Model=31,652=291 AA,Alan Autry Anara Atanes=English, Model=55,112=170 AA,Alvin Ailey ……………. AA,Amedeo Avogadro ACTION ACTION AA,Amy Adams AA,Andre Agasi ALY & AJ AA,Andre Agassi ANDREW ALLEN AA,Anouk Aimée ANGELA AMMONS AA,Ansel Adams ASAF AVIDAN AA,Army Archerd ASKING ALEXANDRIA AA,Art Alexakis AA,Arthur Ashe ATTACK ATTACK! AA,Ashley -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

Linda Hogan and Annie Dillard Bachelor’S Diploma Thesis

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Markéta Tomášková Searching for Home on This Earth: Linda Hogan and Annie Dillard Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Martina Horáková, Ph. D. 2016 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature - 2 - Acknowledgement I am very grateful to my supervisor Dr. Martina Horáková for her guidance, kind support, and valuable comments on the manuscript. I would also like to thank my family, including Riki the dog, for providing me with a cosy and warm dwelling, which made the writing and the completion of this paper possible. - 3 - Searching for Home on This Earth: Linda Hogan and Annie Dillard Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................- 5 - 1 The Perception of ‘Objects’ ............................................................................................- 9 - 1.1 ‘Objects’ in Dwellings ............................................................................................. - 14 - 1.2 ‘Objects’ in Pilgrim at Tinker Creek ....................................................................... - 18 - 2 The Perception of Animals ..............................................................................................- 24 - 2.1 Animals in Dwellings ............................................................................................. -

LIT 202 American Literature II

College of San Mateo Official Course Outline 1. COURSE ID: LIT. 202 TITLE: American Literature II C-ID: ENGL 135 Units: 3.0 units Hours/Semester: 48.0-54.0 Lecture hours Method of Grading: Letter Grade Only Prerequisite: Eligibility for ENGL 100 or ENGL 105 2. COURSE DESIGNATION: Degree Credit Transfer credit: CSU; UC AA/AS Degree Requirements: CSM - GENERAL EDUCATION REQUIREMENTS: E2b. English, literature, Speech Communication CSM - GENERAL EDUCATION REQUIREMENTS: E2c.Communication and Analytical Thinking CSM - GENERAL EDUCATION REQUIREMENTS: E5c. Humanities CSU GE: CSU GE Area C: ARTS AND HUMANITIES: C2 - Humanities (Literature, Philosophy, Languages Other than English) IGETC: IGETC Area 3: ARTS AND HUMANITIES: B: Humanities 3. COURSE DESCRIPTIONS: Catalog Description: Study of American Literature from the end of the U. S. Civil War in 1865 through the modern day. Lectures, discussions, and recorded readings. 4. STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOME(S) (SLO'S): Upon successful completion of this course, a student will meet the following outcomes: 1. Demonstrate familiarity with a variety of representative works of American literature from the 1870s to the present, identifying major literary, cultural, and historical themes. 2. Present a critical, independent analysis of themes in one or more works of American literature from the 1870s to the present in the form of a project, paper, or presentation. 5. SPECIFIC INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES: Upon successful completion of this course, a student will be able to: 1. Demonstrate an understanding of the contexts- historical, intellectual, social, and cultural-of a broad range of American literature from the 1870s to the present. 2. Identify major literary figures and their works in the period. -

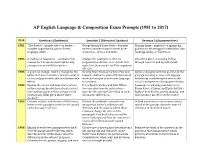

AP English Language & Composition Exam Prompts (1981 to 2017)

AP English Language & Composition Exam Prompts (1981 to 2017) YEAR Question 1 (Synthesis) Question 2 (Rhetorical Analysis) Question 3 (Argumentative) 1981 “The Rattler”- analyze effect on reader – George Bernard Shaw letter – describe Thomas Szasz – argue for or against his consider organization, point of view, writer’s attitude toward mother & her position on the struggle for definition. Use language, detail. cremation – diction and detail readings, study, or experience. 1982 A reading on happiness – summarize his Analyze the strategies or devices Describe a place, conveying feeling reasons for his opinion and explain why (organization, diction, tone, detail) that through concrete and specific detail. you agree or not with his opinion make Gov. Stevenson’s Cat Veto argument effective. 1983 A quote on change - Select a change for the Excerpt from Thomas Carlyle’s Past and Agree or disagree with the position in the better that has occurred or that you want to Present – define Carlyle’s attitude toward passage on living in an era of language occur; analyze its desirable and undesirable work and analyze how he uses language inflation by considering the ethical and effects to convince…. social consequences of language inflation. 1984 Explain the nature and importance of two Percy Bysshe Shelley and John Milton – A passage on a boxing match between or three means by which you keep track of two very short quotes on freedom – Benny Paret, a Cuban, and Emile Griffith – time and discuss how these means reveal describe the concept of freedom in each; Analyze how diction, syntax, imagery, and your person. (Hint given about “inner discuss the differences. -

Let's Talk About It at Davie County Public Library

Let’s Talk About It at Davie County Public Library Davie County Public Library has enjoyed a long history of Let’s Talk About It programming. Below is a listing of LTAI themes and books that we have explored over the years. 2015: Too Hot to Handle? Revisiting Literary Classics (originated by Davie County Public Library) To Kill a Mockingbird The Great Gatsby Of Mice and Men Catcher in the Rye 1984 2014: Muslim Journeys – American Stories Prince Among Slaves The Columbia Sourcebook Acts of Faith A Quiet Revolution The Butterfly Mosque 2013: Divergent Cultures – the Middle East in Literature Reading Lolita in Tehran Palace Walk A Perfect Peace Three Cups of Tea Nine Parts of Desire 2012: Making Sense of the Civil War March by Geraldine Brooks Crossroads of Freedom: Antietam by James McPherson America's War, a new anthology of historical fiction, diaries, memoirs, and short stories, ed. Edward L. Ayers. 2011: Altered Landscapes: North Carolina's Changing World Salt: A Novel by Isabel Zuber Garden Spells by Sarah Addison Allen If You Want Me To Stay by Michael Parker Blood Done Sign My Name: A True Story by Timothy Tyson Plant Life: A Novel by Pamela Duncan 2010: Law and Literature: The Eva R. Rubin Series Billy Budd & Other Stories by Herman Melville The Tragedy of Pudd'nhead Wilson by Mark Twain A Lesson Before Dying by Ernest Gaines Snow Falling on Cedars by David Guterson The Emperor of Ocean Park by Stephen Carter 1 2009: Discovering the Literary South: The Louis D. Rubin, Jr. Series Gap Creek: The Story of a Marriage by Robert Morgan A Virtuous Woman by Kaye Gibbons The Jew Store by Stella Suberman Clover by Dori Sanders The Coal Tattoo: A Novel by Silas House 2008: Family: the Way We Were, the Way We Are This House of Sky by Ivan Doig Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry and The Glass Menagerie by Tennessee Williams Ordinary People by Judith Guest Points of View: an Anthology of Short Stories ed. -

The Poetics and Politics of Liminality: New Transcendentalism in Contemporary American Women’S Writing

The Poetics and Politics of Liminality: New Transcendentalism in Contemporary American Women’s Writing by Teresa O’Rourke A Doctoral Thesis Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy of Loughborough University 21st June 2017 © by Teresa O’Rourke 2017 ABSTRACT By setting the writings of Etel Adnan, Annie Dillard, Marilynne Robinson and Rebecca Solnit into dialogue with those of the New England Transcendentalists, this thesis proposes a New Transcendentalism that both reinvigorates and reimagines Transcendentalist thought for our increasingly intersectional and deterritorialized contemporary context. Drawing on key re-readings by Stanley Cavell, George Kateb and Branka Arsić, the project contributes towards the twenty-first-century shift in Transcendentalist scholarship which seeks to challenge the popular image of New England Transcendentalism as uncompromisingly individualist, abstract and ultimately the preserve of white male privilege. Moreover, in its identification and examination of an interrelated poetics and politics of liminality across these old and new Transcendentalist writings, the project also extends the scope of a more recent strain of Transcendentalist scholarship which emphasises the dialogical underpinnings of the nineteenth-century movement. The project comprises three central chapters, each of which situates New Transcendentalism within a series of vertical and lateral dialogues. The trajectory of my chapters follows the logic of Emerson’s ‘ever-widening circles’, in that each takes a wider critical lens through which to explore the dialogical relationship between my four writers and the New England Transcendentalists. In Chapter 1 the focus is upon anthropological theories of liminality; in Chapter 2 upon feminist interventions within psychoanalysis; and in Chapter 3 upon the revisionary work of Post-West criticism. -

Annie Dillard: at the Altar of Nature Kelley A

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Masters Theses Graduate Research and Creative Practice 8-2018 Annie Dillard: At the Altar of Nature Kelley A. Kasul Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Kasul, Kelley A., "Annie Dillard: At the Altar of Nature" (2018). Masters Theses. 892. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/theses/892 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research and Creative Practice at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Annie Dillard: At the Altar of Nature Kelley A. Kasul A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of GRAND VALLEY STATE UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts English August 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank my mother, Ruth Kasul, for all your time reading and re-reading this thesis numerous times. I am grateful for your help with ideas for revision. I appreciate that you helped me find a topic I was excited about as well. I also wish to thank Avis Hewitt, PhD. for your help and guid- ance through this process. Thank you for sparking my interest in Annie Dillard and helping it flourish. It is greatly appreci- ated. 3 ABSTRACT This thesis intends to delve into Annie Dillard’s time spent at Tinker Creek. Why Dillard chose to go into nature is critiqued, as well as what she found. -

MAIN LIBRARY Author Title Areas of History Aaron, Daniel, and Robert

MAIN LIBRARY Author Title Areas of History Aaron, Daniel, and Robert Bendiner The Strenuous Decade: A Social and Intellectual Record of the 1930s United States Aaronson, Susan A. Are There Trade-Offs When Americans Trade? United States Aaronson, Susan A. Trade and the American Dream: A Social History of Postwar Trade Policy United States Abbey, Edward Abbey's Road United States Abdill, George B. Civil War Railroads Military Abel, Donald C. Fifty Readings Plus: An Introduction to Philosophy World Abels, Richard Alfred The Great Europe Abernethy, Thomas P. A History of the South: The South in the New Nation, 1789-1819 (p.1996) (Vol. IV) United States Abrams, M. H. The Norton Anthology of English Literature Literature Abramson, Rudy Spanning the Century: The Life of W. Averell Harriman, 1891-1986 United States Absalom, Roger Italy Since 1800 Europe Abulafia, David The Western Mediterranean Kingdoms Europe Abzug, Robert H. Cosmos Crumbling: American Reform and the Religious Imagination United States Abzug, Robert Inside the Vicious Heart Europe Achebe, Chinua Things Fall Apart Literature Achenbaum, W. Andrew Old Age in the New Land: The American Experience since 1790 United States Acton, Edward Russia: The Tsarist and Soviet Legacy, 2nd ed. Europe Adams, Arthur E. Imperial Russia After 1861 Europe Adams, Arthur E., et al. Atlas of Russian and East European History Europe Adams, Henry Democracy: An American Novel Literature Adams, James Trustlow The Founding of New England United States Adams, Simon Winston Churchill: From Army Officer to World Leader Europe Adams, Walter R. The Blue Hole Literature Addams, Jane Twenty Years at Hull-House United States Adelman, Paul Gladstone, Disraeli, and Later Victorian Politics Europe Adelman, Paul The Rise of the Labour Party, 1880-1945 Europe Adenauer, Konrad Memoirs, 1945-1953 Europe Adkin, Mark The Charge Europe Adler, Mortimer J. -

The Silences of Annie Dillard

THE SILENCES OF ANNIE DILLARD A Thesis by Robynn Sims Master of Arts, Wichita State University, 2014 Christian Ministries, Tabor College, 2004 Submitted to the Department of English and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 2014 1 © Copyright 2014 by Robynn Sims All Rights Reserved 2 THE SILENCES OF ANNIE DILLARD The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this thesis for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. Kimberly Engber, Committee Chair Mary Waters, Committee Member Robin Henry, Committee Member iii3 DEDICATION To my parents, who taught me to look to the clouds, to the stars iv4 “You were made and set here to give voice to this, your own astonishment.” — Annie Dillard, The Writing Life “Silence makes us pilgrims.” — Henri Nouwen, The Way of the Heart v5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Kimberly Engber, for her guidance and encouragement, as well as my other committee members, Dr. Mary Waters and Dr. Robin Henry, for their insight and thorough analysis. I am grateful for Dr. Engber's willingness to follow this path with me over the last year. Professor Albert Goldbarth offered his time and thoughts, for which I am indebted. Without the gentle leading of Warren Farha and the staff at Eighth Day Books this thesis would have remained unwritten. For my colleagues Parker McConachie and Amanda Crabtree, their engaging conversations helped me form my ideas. -

Pulitzer Prize Winners and Finalists

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70