| Sydney Brenner |

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize Winners Part 4 - 1996 to 2015: from Stem Cell Breakthrough to IVF

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize winners part 4 - 1996 to 2015: from stem cell breakthrough to IVF By Cambridge News | Posted: February 01, 2016 Some of Cambridge's most recent Nobel winners Over the last four weeks the News has been rounding up all of Cambridge's 92 Nobel Laureates, which this week comes right up to the present day. From the early giants of physics like JJ Thomson and Ernest Rutherford to the modern-day biochemists unlocking the secrets of our genome, we've covered the length and breadth of scientific discovery, as well as hugely influential figures in economics, literature and politics. What has stood out is the importance of collaboration; while outstanding individuals have always shone, Cambridge has consistently achieved where experts have come together to bounce their ideas off each other. Key figures like Max Perutz, Alan Hodgkin and Fred Sanger have not only won their own Nobels, but are regularly cited by future winners as their inspiration, as their students went on to push at the boundaries they established. In the final part of our feature we cover the last 20 years, when Cambridge has won an average of a Nobel Prize a year, and shows no sign of slowing down, with ground-breaking research still taking place in our midst today. The Gender Pay Gap Sale! Shop Online to get 13.9% off From 8 - 11 March, get 13.9% off 1,000s of items, it highlights the pay gap between men & women in the UK. Shop the Gender Pay Gap Sale – now. Promoted by Oxfam 1.1996 James Mirrlees, Trinity College: Prize in Economics, for studying behaviour in the absence of complete information As a schoolboy in Galloway, Scotland, Mirrlees was in line for a Cambridge scholarship, but was forced to change his plans when on the weekend of his interview he was rushed to hospital with peritonitis. -

Lasker Interactive Research Nom'18.Indd

THE 2018 LASKER MEDICAL RESEARCH AWARDS Nomination Packet albert and mary lasker foundation November 1, 2017 Greetings: On behalf of the Albert and Mary Lasker Foundation, I invite you to submit a nomination for the 2018 Lasker Medical Research Awards. Since 1945, the Lasker Awards have recognized the contributions of scientists, physicians, and public citizens who have made major advances in the understanding, diagnosis, treatment, cure, and prevention of disease. The Medical Research Awards will be offered in three categories in 2018: Basic Research, Clinical Research, and Special Achievement. The Lasker Foundation seeks nominations of outstanding scientists; nominations of women and minorities are encouraged. Nominations that have been made in previous years are not automatically reconsidered. Please see the Nomination Requirements section of this booklet for instructions on updating and resubmitting a nomination. The Foundation accepts electronic submissions. For information on submitting an electronic nomination, please visit www.laskerfoundation.org. Lasker Awards often presage future recognition of the Nobel committee, and they have become known popularly as “America’s Nobels.” Eighty-seven Lasker laureates have received the Nobel Prize, including 40 in the last three decades. Additional information on the Awards Program and on Lasker laureates can be found on our website, www.laskerfoundation.org. A distinguished panel of jurors will select the scientists to be honored with Lasker Medical Research Awards. The 2018 Awards will -

Advertising (PDF)

Share the wonders of the brain and mind with A PUBLIC INFORMATION INITIATIVE OF: Seeking resources to communicate with the public about neuroscience? Educating others through Brain Awareness activities? BrainFacts.org can help you communicate how the brain works. Explore BrainFacts.org for easy-to-use, accessible resources including: s Information about hundreds of diseases and disorders s Concepts about brain function s Educational tools s Multimedia tools and a social media community s Interviews and discussions with leading researchers; and more Visit BrainFacts.org Give to the Friends of SfN Fund Join us in forging the future of neuroscience Support a future of discovery and progress through travel awards and public education and outreach programs. To inquire about specific initiatives or to make a tax-deductible contribution, visit SfN.org or email: [email protected]. THE HISTORY OF NEUROSCIENCE IN AUTOBIOGRAPHY THE LIVES AND DISCOVERIES OF EMINENT SENIOR NEUROSCIENTISTS CAPTURED IN AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL BOOKS AND VIDEOS The History of Neuroscience in Autobiography Series Edited by Larry R. Squire Outstanding neuroscientists tell the stories of their scientific work in this fascinating series of autobiographical essays. Within their writings, they discuss major events that shaped their discoveries and their influences, as well as people who inspired them and helped shape their careers as neuroscientists. The History of Neuroscience in Autobiography, Vol. 1 The History of Neuroscience in Autobiography, Vol. 4 Denise Albe-Fessard, Julius Axelrod, Peter O. Bishop, Per Andersen, Mary Bunge, Jan Bures, Jean-Pierre Changeux, Theodore H. Bullock, Irving T. Diamond, Robert Galambos, John Dowling, Oleh Hornykiewicz, Andrew Huxley, Jac Sue Viktor Hamburger, Sir Alan L. -

Discovery of the Secrets of Life Timeline

Discovery of the Secrets of Life Timeline: A Chronological Selection of Discoveries, Publications and Historical Notes Pertaining to the Development of Molecular Biology. Copyright 2010 Jeremy M. Norman. Date Discovery or Publication References Crystals of plant and animal products do not typically occur naturally. F. Lesk, Protein L. Hünefeld accidentally observes the first protein crystals— those of Structure, 36;Tanford 1840 hemoglobin—in a sample of dried menstrual blood pressed between glass & Reynolds, Nature’s plates. Hunefeld, Der Chemismus in der thierischen Organisation, Robots, 22.; Judson, Leipzig: Brockhaus, 1840, 158-63. 489 In his dissertation Louis Pasteur begins a series of “investigations into the relation between optical activity, crystalline structure, and chemical composition in organic compounds, particularly tartaric and paratartaric acids. This work focused attention on the relationship between optical activity and life, and provided much inspiration and several of the most 1847 HFN 1652; Lesk 36 important techniques for an entirely new approach to the study of chemical structure and composition. In essence, Pasteur opened the way to a consideration of the disposition of atoms in space.” (DSB) Pasteur, Thèses de Physique et de Chimie, Presentées à la Faculté des Sciences de Paris. Paris: Bachelier, 1847. Otto Funcke (1828-1879) publishes illustrations of crystalline 1853 hemoglobin of horse, humans and other species in his Atlas der G-M 684 physiologischen Chemie, Leizpig: W. Englemann, 1853. Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace publish the first exposition of the theory of natural selection. Darwin and Wallace, “On the Tendency of 1858 Species to Form Varieties, and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and G-M 219 Species by Natural Means of Selection,” J. -

The Sui Generis Sydney Brenner,” by Thoru Pederson, Which Was First Published June 10, 2019; 10.1073/ Pnas.1907536116 (Proc

Correction RETROSPECTIVE Correction for “The sui generis Sydney Brenner,” by Thoru Pederson, which was first published June 10, 2019; 10.1073/ pnas.1907536116 (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116,13155–13157). The author notes that, on page 13155, left column, second paragraph, lines 13–14, “Cyril Hinshelwood at Oxford, a leading figure in the early bacteriophage field” has been revised to read “Cyril Hinshelwood at Oxford, a chemist turned bacteriologist.” Additionally, in the original version of this article, the author stated that the experiments performed by Brenner and Crick involved chemically induced mutations in given DNA letters. In fact, most of the data were from spontaneous mutations. We have removed this incorrect assertion. The online version of the article has been corrected. Published under the PNAS license. Published online July 15, 2019. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1910910116 CORRECTION www.pnas.org PNAS | July 23, 2019 | vol. 116 | no. 30 | 15307 Downloaded by guest on October 1, 2021 RETROSPECTIVE The sui generis Sydney Brenner RETROSPECTIVE Thoru Pedersona,1 Sydney Brenner died on April 5, 2019, at age 92. His fame arose from three domains in which he operated with uncommon intellectual vibrancy. First were his prescient ideas and breakthrough experiments that defined the DNA genetic code and how the informa- tion it contains is transmitted into proteins. Second, in a later career, he developed a model organism, the roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans, to determine how the cells of an animal descend, one by one, along pathways of increasing specialization. Last was his be- guiling skill as an intellectual sharpshooter, often sur- prising colleagues by the immediacy of his “take” of a problem, even ones somewhat beyond his ken. -

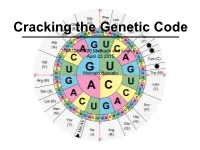

MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 23 2015 Marcelo Bassalo

Cracking the Genetic Code MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 23 2015 Marcelo Bassalo Last Tuesday… Nirenberg and Matthaei: RNA is the template for protein synthesis (poly-U —> phenylalanine) Thursday! Francis Crick Sydney Brenner • 1927 - today • Born in South Africa • BS in Anatomy and Physiology • MS in Cytogenetics • PhD in Physical Chemistry from Oxford • Joined Salk Institute in 1976 • Established C. elegans as model organism for developmental biology • 2002 Nobel Prize Physiology or Medicine Leslie Barnett • 1920 - 2002 • Born in London • BS in Dairying • Worked with Brenner for most part of her life Cracking the Genetic Code Bacteriophage T4 Escherichia coli Figure from Brock Biology of Microorganisms Cracking the Genetic Code Viral Plaques Why Phage T4? • Plaques are an easy screening system • Allows investigation of rare events (trillions of tries in a single LB plate) • rII locus: phenotypes allows genetic mapping (Benzer) rII genes E. coli K-12 (K) E. coli B (B) WT ✓ ✓ A B non-leaky larger/irregular plaques mutation (r-plaque) (null) X A B leaky larger/irregular plaques mutation ✓ (r-plaque) (partial function) A B Why Phage T4? B’ B’/B’’ Grow in B null mutation No growth in K Grow in B null mutation Growth in K B’’ WT { Grow in B No growth in K # plaques (K) Distance (B’ to B’’) = # plaques (B) The Genetic Code is not overlapping Evidence comes from previous studies: • Tobacco mosaic virus RNA: mutations in RNA change only 1 amino acid (Tsugita et. al) • Abnormal human hemoglobins shows only single amino acid changes (Watson -

Nobel Laureates in Physiology Or Medicine

All Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine 1901 Emil A. von Behring Germany ”for his work on serum therapy, especially its application against diphtheria, by which he has opened a new road in the domain of medical science and thereby placed in the hands of the physician a victorious weapon against illness and deaths” 1902 Sir Ronald Ross Great Britain ”for his work on malaria, by which he has shown how it enters the organism and thereby has laid the foundation for successful research on this disease and methods of combating it” 1903 Niels R. Finsen Denmark ”in recognition of his contribution to the treatment of diseases, especially lupus vulgaris, with concentrated light radiation, whereby he has opened a new avenue for medical science” 1904 Ivan P. Pavlov Russia ”in recognition of his work on the physiology of digestion, through which knowledge on vital aspects of the subject has been transformed and enlarged” 1905 Robert Koch Germany ”for his investigations and discoveries in relation to tuberculosis” 1906 Camillo Golgi Italy "in recognition of their work on the structure of the nervous system" Santiago Ramon y Cajal Spain 1907 Charles L. A. Laveran France "in recognition of his work on the role played by protozoa in causing diseases" 1908 Paul Ehrlich Germany "in recognition of their work on immunity" Elie Metchniko France 1909 Emil Theodor Kocher Switzerland "for his work on the physiology, pathology and surgery of the thyroid gland" 1910 Albrecht Kossel Germany "in recognition of the contributions to our knowledge of cell chemistry made through his work on proteins, including the nucleic substances" 1911 Allvar Gullstrand Sweden "for his work on the dioptrics of the eye" 1912 Alexis Carrel France "in recognition of his work on vascular suture and the transplantation of blood vessels and organs" 1913 Charles R. -

The Promise of Synthetic Biology

Building Living Machines with Biobricks The Promise of Synthetic Biology Professor Richard Kitney, Professor Paul Freemont Support by Matthieu Bultelle, Dr Robert Dickinson, Dr Suhail Islam, Kirsten Jensen, Paul Kitney, Dr Duo Lu, Dr Chueh Loo Poh, Vincent Rouilly, Baojun Wang. The Fathers of Biological Engineering Imperial College London Department of Bioengineering Division of Molecular Biosciences Norbert Wiener American Mathematician (1894–1964) Throughout his life Wiener had many extra- mathematical interests, especially in biology and philosophy. At Harvard his studies in philosophy led him to an interest in mathematical logic and this was the subject of his doctoral thesis, which he completed at the age of 18. In 1920 he joined the faculty of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he became professor of mathematics (1932). He made significant contributions to a number of areas of mathematics including harmonic analysis and Fourier transforms. Norbert Wiener is best known for his theory of cybernetics, the comparative study of control and communication in humans and machines. He also made significant contributions to the development of computers and calculators. The Feedback Loop: A crucial concept of Cybernetics Claude Elwood Shannon American Mathematician (1916–2001) Shannon graduated from the University of Michigan in 1936. He later worked both at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Bell Telephone Laboratories. In 1958 he returned to MIT as Donner Professor of Science, held until his retirement in 1978. Shannon's greatest contribution was in laying the mathematical foundations of communication theory. The resulting theory found applications in such wide-ranging fields as circuit design, communication technology in general, and even in biology, psychology, semantics, and linguistics. -

SYDNEY BRENNER Salk Institute, 100010 N

NATURE’S GIFT TO SCIENCE Nobel Lecture, December 8, 2002 by SYDNEY BRENNER Salk Institute, 100010 N. Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, California, USA, and King’s College, Cambridge, England. The title of my lecture is “Nature’s gift to Science.” It is not a lecture about one scientific journal paying respects to another, but about how the great di- versity of the living world can both inspire and serve innovation in biological research. Current ideas of the uses of Model Organisms spring from the ex- emplars of the past and choosing the right organism for one’s research is as important as finding the right problems to work on. In all of my research these two decisions have been closely intertwined. Without doubt the fourth winner of the Nobel prize this year is Caenohabditis elegans; it deserves all of the honour but, of course, it will not be able to share the monetary award. I intend to tell you a little about the early work on the nematode to put it into an intellectual perspective. It bridges, both in time and concept, the biol- ogy we practice today and the biology that was initiated some fifty years ago with the revolutionary discovery of the double-helical structure of DNA by Watson and Crick. My colleagues who follow will tell you more about the worm and also recount their incisive research on the cell lineage and on the genetic control of all death. To begin with, I can do no better than to quote from the paper I published in 1974 (1). -

Timeline Code Dnai Site Guide

DNAi Site Guide 1 DNAi Site Guide Timeline Pre 1920’s Johann Gregor Mendel, Friedrich Miescher, Carl Erich Correns, Hugo De Vries, Erich Von Tschermak- Seysenegg, Thomas Hunt Morgan 1920-49 Hermann Muller, Barbara McClintock, George Wells Beadle, Edward Lawrie Tatum, Joshua Lederberg, Oswald Theodore Avery 1950-54 Erwin Chargaff, Rosalind Elsie Franklin, Martha Chase, Alfred Day Hershey, Linus Pauling, James Dewey Watson, Francis Harry Compton Crick, Seymour Benzer 1955-59 Francis Harry Compton Crick, Paul Charles Zamecnik, Mahlon Hoagland, Matthew Stanley Meselson, Franklin William Stahl, Arthur Kornberg 1960’s Sydney Brenner, Marshall Warren Nirenberg, François Jacob, Jacques Lucien Monod, Roy John Britten 1970’s David Baltimore, Howard Martin Temin, Stanley Norman Cohen, Herbert W. Boyer, Richard John Roberts, Phillip Allen Sharp, Roger Kornberg, Frederick Sanger 1980’s Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard, Eric Francis Wieschaus, Kary Mullis, Thomas Robert Cech, Sidney Altman, Mario Renato Capecchi 1990-2000 Mary-Claire King, Stephen P.A. Fodor, Patrick Henry Brown, John Craig Venter Francis Collins, John Sulston Code Finding the structure Problem What is the structure of DNA? DNAi Site Guide 2 Players Erwin Chargaff, Rosalind Franklin, Linus Pauling, James Watson and Francis Crick, Maurice Wilkins Pieces of the puzzle Wilkins' X-ray, Pauling's triple helix, Franklin's X-ray, Watson's base pairing, Chargaff's ratios Putting it together DNA is a double-stranded helix. Copying the code Problem How is DNA copied? Players James Watson and Francis Crick, Sydney Brenner, François Jacob, Matthew Meselson, Arthur Kornberg Pieces of the puzzle The Central Dogma, Semi-conservative replication Models of DNA replication, The RNA experiment, DNA synthesis Putting it together DNA is used as a template for copying information. -

DNA Discovery Pioneer James Watson Pays Cambridge Tribute to Colleague Francis Crick

DNA discovery pioneer James Watson pays Cambridge tribute to colleague Francis Crick By chris elliott | Posted: June 10, 2016 Controversial scientist James Watson returned to the city where he cracked the secret of DNA more than 60 years ago – to pay tribute to the man who helped him do it. In 1953, Prof Watson and fellow researcher Francis Crick, working in the city's famous Cavendish Laboratory, unravelled the structure of deoxyribonucleic acid, the genetic material that determines hereditary characteristics such as eye and hair colour. After the 'double helix' breakthrough the two men famously went for a celebratory pint in The Eagle pub, where the story goes that regulars heard them talking about discovering 'the secret of life', and thought they were drunk. The duo's work won them and collaborator Maurice Wilkins the Nobel Prize in 1962. Crick died in 2004, and yesterday his erstwhile colleague came back to Cambridge's MRC (Medical Research Council) Laboratory of Molecular Biology to deliver a special talk about him, marking the centenary of Crick's birth. Prof Watson, 88, who has sparked controversy in recent years for his allegedly racist views, worked as a visitor at the MRC Unit, the precursor to the LMB, between 1951 and 1953, and also in 1955-56 and 1961. Crick was a founding member of the LMB when it opened in 1962, remaining there until 1976, working alongside another future Cambridge Nobel Laureate, Sydney Brenner. To give the talk, organised by Gonville & Caius College, Prof Watson came to England from America, where he is Chancellor Emeritus at New York's Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. -

Sydney Brenner's Life in Science 1927–2019

Sydney Brenner’s Life in Science 1927–2019 A Heroic Voyage: Sydney Brenner’s Life in Science Copyright © 2019 Agency for Science, Technology and Research Biomedical Research Council Agency for Science, Technology and Research 20 Biopolis Way, #08-01 Singapore 138668 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. This companion booklet was originally published in conjunction with the 2015 Sydney Brenner Scientific Symposium and Exhibition, held at Singapore's Biopolis scientific hub. Agency for Science, Cold Spring Technology and Research, Harbor Laboratory, Singapore New York c A Heroic Voyage: Sydney Brenner's Life in Science ONE OF AN EXCELLENT OUR OWN TRAVEL Message by Lim Chuan Poh COMPANION Former Chairman Agency for Science, Technology and Research Message by James Watson Chancellor Emeritus Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory hirty years ago, when Sydney times to reach over S$29 billion in 2012, ver the course of my career, Then there were the exciting, frenetic Brenner first visited Singapore, contributing to 5% of Singapore’s GDP. I’ve had the privilege of years of the Human Genome Project. We the state of research, especially While Singapore’s success in this area tackling some of the most kept up our exchanges, with him in the UK in biomedical sciences, was certainly cannot be attributed to any one fundamental questions in and me in the US, doing as much science as vastly different from what it is person, few have been as deeply involved biology, working alongside possible while being responsible for entire Ttoday.