William Playfair Excerpt More Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Erasmus Darwin - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Erasmus Darwin - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Erasmus Darwin(12 December 1731 – 18 April 1802) Erasmus Darwin was an English physician who turned down George III's invitation to be a physician to the King. One of the key thinkers of the Midlands Enlightenment, he was also a natural philosopher, physiologist, abolitionist, inventor and poet. His poems included much natural history, including a statement of evolution and the relatedness of all forms of life. He was a member of the Darwin–Wedgwood family, which includes his grandsons Charles Darwin and Francis Galton. Darwin was also a founding member of the Lunar Society of Birmingham, a discussion group of pioneering industrialists and natural philosophers. <b>Early Life</b> Born at Elston Hall, Nottinghamshire near Newark-on-Trent, England, the youngest of seven children of Robert Darwin of Elston (12 August 1682–20 November 1754), a lawyer, and his wife Elizabeth Hill (1702–1797). The name Erasmus had been used by a number of his family and derives from his ancestor Erasmus Earle, Common Sergent of England under Oliver Cromwell. His siblings were: Robert Darwin (17 October 1724–4 November 1816) Elizabeth Darwin (15 September 1725–8 April 1800) William Alvey Darwin (3 October 1726–7 October 1783) Anne Darwin (12 November 1727–3 August 1813) Susannah Darwin (10 April 1729–29 September 1789) John Darwin, rector of Elston (28 September 1730–24 May 1805) He was educated at Chesterfield Grammar School, then later at St John's College, Cambridge. He obtained his medical education at the University of Edinburgh Medical School. -

Scotland and the Americas 1600 to 1800 Jose Amor Y Vazquez

SCOTLAND AND THE AMERICAS 1600 TO 1800 JOSE AMOR Y VAZQUEZ JOHN BOCKSTOCE T. KIMBALL BROOKER J. CARTER BROWN VINCENT J. BUONANNO MARY MAPLES DUNN GEORGE D. EDWARDS, JR. VARTAN GREGORIAN, Chairman Board of Governors ARTEMIS A. W. JOUKOWSKY of the John Carter Brown FREDERICK LIPPITT Library JOSE E. MINDLIN EUSTASIO RODRIGUEZ ALVAREZ CLINTON I. SMULLYAN, JR. FRANK S. STREETER MERRILY TAYLOR CHARLES C. TILLINGHAST, JR. LADISLAUS VON HOFFMANN WILLIAM B. WARREN CHARLES II. WATTS, II Sponsors arid Patrons Sponsors MR. AND MRS. REINALDO HERRERA HR OS WITH A SOCIETY TIIE DRUE HEINZ FOUNDATION THE DUNVEGAN FOUNDATION MR. AND MRS. JAY I. KISLAK MR. SIDNEY LAPIDUS Honorary Patron MR. MAGNUS LINKLATER MR. GEORGE S. LOWRY LORD PERTH OF PERTHSHIRE MR. N. DOUGLAS MACLEOD DR. ALEXANDER C. MCLEOD Patrons Committee MR. AND MRS. ROBERT L. MCNEIL, JR. MRS. STANLEY D. SCOTT THE HONORABLE J. WILLIAM MIDDENDORF, II MR. TIMOTHY C. FORBES, Co-chairmen MR. RICHARD W. MONCRIEF THE HONORABLE J. SINCLAIR ARMSTRONG MR. GEORGE PARKER MR. GEORGE D. EDWARDS. JR. MR. WILLIAM S. REESE MRS. ROBERT H. I. GODDARD MR. AND MRS. DAVID F. REMINGTON DR. ALEXANDER C. MCLEOD MR. ROBERT A. ROBINSON MRS. PETER SAINT GERMAIN MR. MORDECAI K. ROSENFELD MR. J. THOMAS TOUCHTON THE ROYAL BANK OF SCOTLAND MR. CHARLES M. ROYCE MRS. JANE GREGORY RUBIN THE HONORABLE J. SINCLAIR ARMSTRONG MR. AND MRS. PETER SAINT GERMAIN MRS. VINCENT ASTOR MR. AND MRS. STANLEY DEFOREST SCOTT MR. LYMAN G. BLOOMINGDALE DR. AND MRS. THOMAS SCULCO DR. JOHN AND LADY ROMAYNE BOCKSTOCE MR. AND MRS. ROBERT B. SHEA MR. AND MRS. -

The Library of Robert Carter of Nomini Hall

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1970 The Library of Robert Carter of Nomini Hall Katherine Tippett Read College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Read, Katherine Tippett, "The Library of Robert Carter of Nomini Hall" (1970). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624697. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-syjc-ae62 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE LIBRARY OF ROBERT CARTER OF NOMINI HALL A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Katherine Tippett Read 1970 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, May 1970 Jane Cdrson, Ph. D Robert Maccubbin, Ph. D. John JEJ Selby, Pm. D. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writer wishes to express her appreciation to Miss Jane Carson, under whose direction this investigation was conducted, for her patient guidance and criticism throughout the investigation. The author is also indebted to Mr. Robert Maccubbin and Mr. John E. Selby for their careful reading and criticism of the manuscript. -

Dissenters and Liberals in the Drive for Religious Freedom in Virginia

“An Asylum to the Persecuted and Oppressed of Every Nation and Religion”: Dissenters and Liberals in the Drive for Religious Freedom in Virginia A PAPER SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF LIBERTY UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY DR. SAMUEL C. SMITH, CHAIR DR. BRIAN MELTON BY SHELLY D. BAILESS APRIL 21, 2010 LYNCHBURG, VIRGINIA Table of Contents INTRODUCTION: 2 CHAPTER 1: HISTORY, HISTORIOGRAPHY, AND DEFINITION OF TERMS 6 History: 6 Historiography: 8 Definition of Terms: 28 Jefferson, Madison, and Locke: 31 CHAPTER 2: THE DISSENTERS: PRESBYTERIANS AND BAPTISTS FROM 1738 TO 1776 38 CHAPTER 3: JEFFERSON AND VIRGINIA’S REVISION OF LAWS: 1776-1781 65 CHAPTER 4: JAMES MADISON AND THE VIRGINIA STATUTE FOR ESTABLISHING RELIGIOUS FREEDOM, 1782- 1786 90 CONCLUSION: 115 BIBLIOGRAPHY 120 1 Introduction: America‟s religious heritage, our national understanding of the relationship between church and state, and the religious convictions of our Founding Fathers have recently taken prominence in historical and political debate. Professional scholars and journalists continually produce material in their efforts to determine whether the original ideas of the American Republic created a uniquely Christian or secular state. Since the days of colonial settlement the relationship between church and state has been a topic for heated debate. Few political subjects rely on a detailed understanding of history as does the issue of American religious liberty and church-state separation. Knowledge of the political struggle regarding this relationship in Virginia is integral to the larger national debate on the subject, since many of the legislators who first had to contend with the issue were the lawmakers who helped shape the national government. -

Medical School of Maine Student Theses 1 Thesis Title Author

Medical School of Maine Student Theses Thesis Title Author Graduation Year Water Randall, Wheeler 1821 Ergot Austin, Samuel 1822 Cathartics Baker, George Griswold 1822 Strammonium Bowles, Green Berry 1822 The Heart and Organization Coffin, James 1822 Pulmonary Consumption Duncan, John 1822 Bloodletting Frost, George 1822 Wounds of the Abdomen Hall, James 1822 Group Pulsifer, Moses Rust 1822 Blood Root Quimby, Asa 1822 Group Rea, Albus 1822 Phthisis Pulmonalis Reed, Ariel 1822 Disease of Digestive Organs Richer, John 1822 Foreign Bodies in L'Esophagus Simpson, Ahimaaz Blanchard 1822 Strychnas Vox Vomica Tinker, George Washington 1822 Acute Rheumatism Atkinson, John 1823 Percussion and Mediate Ayscultation in Diseases of the Chest Bell, John 1823 Insanity Bourne, Thomas Perkins 1823 Use of the Oxy-Muriate of Mercury in the Cure of Syphilis Bradbury, Samuel Crockett 1823 Ulcers Bridgham, Roland Hammond 1823 Conversion of Diseases Cobb, Jedidiah 1823 Diseases of Brain Injury Cummings, Sumner 1823 Menstruation Flagg, Melzer 1823 Typhus Fever Fogg, James 1823 Puerperal Fever Garcelon, Daniel 1823 Hemorrhage Hamlin, Castillo 1823 On the Efficacy of the Sulphurous Fumigation in the Treatment of Culaneous & Other Haynes, John P. 1823 Diseases Eupatorium Perfoliatum Heald, Asa 1823 Haemorrhois Lufkin, Aaron 1823 Circulation of Blood Martin, Anselm 1823 The Nature of Dropsy, Particularly those Species of Its Denominated Hydrothorax and Morril, Samuel 1823 Ascites Cholera Infection Pierce, Seth 1823 Medical Police Pratt, Titus Collins 1823 Physiology -

Thinking About Slavery at the College of William and Mary

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 21 (2012-2013) Issue 4 Article 6 May 2013 Thinking About Slavery at the College of William and Mary Terry L. Meyers Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons Repository Citation Terry L. Meyers, Thinking About Slavery at the College of William and Mary, 21 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 1215 (2013), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol21/iss4/6 Copyright c 2013 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj THINKING ABOUT SLAVERY AT THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY Terry L. Meyers* I. POST-RECONSTRUCTION AND ANTE-BELLUM Distorting, eliding, falsifying . a university’s memory can be as tricky as a person’s. So it has been at the College of William and Mary, often in curious ways. For example, those delving into its history long overlooked the College’s eighteenth century plantation worked by slaves for ninety years to raise tobacco.1 Although it seems easy to understand that omission, it is harder to understand why the College’s 1760 affiliation with a school for black children2 was overlooked, or its president in 1807 being half-sympathetic to a black man seeking to sit in on science lectures,3 or its awarding an honorary degree to the famous English abolitionist Granville Sharp in 1791,4 all indications of forgotten anti-slavery thought at the College. To account for these memory lapses, we must look to a pivotal time in the late- nineteenth and early-twentieth century when the College, Williamsburg, and Virginia * Chancellor Professor of English, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia, [email protected]. -

2. the Franklin Circle Starts Modern England

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 23, Number 7, February 9, 1996 around 1671, Leibniz lays down the economic policies of the to acquire stocks in existing ones.... "Society" as follows: "To obtain more from lended monnies, than the rate of interest. ... From 'ideas,' to national industry "To grant Priviledges inside thecountry for everything, "To Expand and Improve the Arts and Sciences. that excludes foreign priviledges, and this without making "To preserve useful ideas, inventions and experiments ... anything more expensive. and to verify them with the help of models and tests; or if "To obtain Priviledges outside the country for all activi verified, to exploit them on a largerscale, than a private person ties and manufactures that are new, and have not yet been could do. realized or produced. "To combine Theories and Experiments, to remedy the "It is therefore to be achieved, that we be able to produce defects of the one with the other. everything better here, than elsewhere, in such a way that we "By putting together various experiments and inventions, can exclude them [foreign manufactures] without Privi to render useful that which is isolated and incomplete.... ledges, but by the favorable cost of all manufactures, provided "To provide poor students the possibility to support them only that the effort be undertaken, to produce them more selves in order to continue their studies, and to earn their economically, than [abroad]. bread, for their own advantage and for the benefit of the "To conserve and expand the Fund by a continuous Circu Society.... lation, and to undertake all enterprises that are pleasing to "To improve the Schools. -

NEWSLETTER Issue: 492 - January 2021

i “NLMS_492” — 2020/12/21 — 10:40 — page 1 — #1 i i i NEWSLETTER Issue: 492 - January 2021 RUBEL’S MATHEMATICS FOUR PROBLEM AND DECADES INDEPENDENCE ON i i i i i “NLMS_492” — 2020/12/21 — 10:40 — page 2 — #2 i i i EDITOR-IN-CHIEF COPYRIGHT NOTICE Eleanor Lingham (Sheeld Hallam University) News items and notices in the Newsletter may [email protected] be freely used elsewhere unless otherwise stated, although attribution is requested when EDITORIAL BOARD reproducing whole articles. Contributions to the Newsletter are made under a non-exclusive June Barrow-Green (Open University) licence; please contact the author or David Chillingworth (University of Southampton) photographer for the rights to reproduce. Jessica Enright (University of Glasgow) The LMS cannot accept responsibility for the Jonathan Fraser (University of St Andrews) accuracy of information in the Newsletter. Views Jelena Grbic´ (University of Southampton) expressed do not necessarily represent the Cathy Hobbs (UWE) views or policy of the Editorial Team or London Christopher Hollings (Oxford) Mathematical Society. Robb McDonald (University College London) Adam Johansen (University of Warwick) Susan Oakes (London Mathematical Society) ISSN: 2516-3841 (Print) Andrew Wade (Durham University) ISSN: 2516-385X (Online) Mike Whittaker (University of Glasgow) DOI: 10.1112/NLMS Andrew Wilson (University of Glasgow) Early Career Content Editor: Jelena Grbic´ NEWSLETTER WEBSITE News Editor: Susan Oakes Reviews Editor: Christopher Hollings The Newsletter is freely available electronically at lms.ac.uk/publications/lms-newsletter. CORRESPONDENTS AND STAFF LMS/EMS Correspondent: David Chillingworth MEMBERSHIP Policy Digest: John Johnston Joining the LMS is a straightforward process. For Production: Katherine Wright membership details see lms.ac.uk/membership. -

William Small and the Making of Thomas Jefferson's Mind

\~ #',~tJ'.. \' .. -~ The Assay Office, Birmingham, England William Small and the Making of Thomas Jefferson's Mind By Cynthia L. Miller It was my great good fortune, and death, Jefferson was a seventy-seven ment and to a better acquaintance whatprobably fixed the destinies ofmy year old ruminating on the day in with the thinking of Francis Bacon, life that Dr. Wm. Small ofScotland was 1760, when he was yet sixteen, that he Isaac Newton, and John Locke--Jef then professor ofMathematics, a man enrolled in the College ofWilliam and ferson's heroes the rest of his life. The profound in most ofthe useful branches Mary in Virginia and found in Small a professor was nine years Jefferson's se of science, with a happy talent ofcom teacher, mentor, and friend. nior and just five years himself reo munication, correct and gentlemanly Small taught math, physics, and moved from university. manners, & an enlarged and liberal metaphysic&-the domains of natural mind. He, most happily for me, became philosophy-in what is now called the MALL WAS BORN to the soon af;t(u;hed to me, & made me his Wren Building at the west end of Reverend James Small and daily companion when not engaged in Williamsburg's Duke of Gloucester his wife, Lilias, on October 13, the school; and from his conversation I Street. Jefferson came to him with an S1734, in Carmyllie, Forfar· got my first views of the expansion of education begun at five in a plantation shire, in eastern Scotland. He grew up science, & of the system of things in school. -

ROGERS-DOCUMENT-2018.Pdf

Abstract Jefferson’s Sons: Notes on the State of Virginia and Virginian Antislavery, 1760–1832 by Cara J. Rogers This dissertation examines the fascinating early life of Thomas Jefferson’s book, Notes on the State of Virginia, from its innocuous composition in the early 1780s to its appropriation as a political weapon by both pro and antislavery forces in the early nineteenth century. Initially written as a statistical introduction to Virginia for French readers, Jefferson’s book evolved into an intellectual tour de force that covered almost all facets of the state’s natural and political realms. As part of an antislavery education strategy, Jefferson also decided to include a treatise on the nature of racial difference, as well as a manifesto on the corrupting power of slavery in a republic and a plan for emancipation and colonization. In consequence, his book—for better or worse—defined the boundaries of future debates over the place of black people in American society. Although historians have rightly criticized Jefferson for his racism and failure to free his own slaves, his antislavery intentions for the Notes have received only cursory notice, partly because the original manuscript was not available for detailed examination until recently. By analyzing Jefferson’s complex revision process, this dissertation traces the ways in which his views on race and slavery evolved as he considered how best to persuade younger slaveholders to embrace emancipation. It then moves beyond Jefferson to examine contemporary responses to the Notes from white and black intellectuals and politicians, concluding with an attempt by Jefferson’s grandson to implement elements of the Notes’ emancipation plan during Virginia’s 1831-32 slavery debates. -

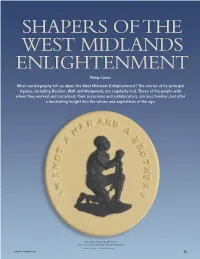

MIDLANDS ENLIGHTENMENT Philip Carter

THE INDUSTRIAL ENLIGHTENMENT SHAPERS OF THE WEST MIDLANDS ENLIGHTENMENT Philip Carter What can biography tell us about the West Midlands Enlightenment? The stories of its principal figures, including Boulton, Watt and Wedgwood, are regularly told. Those of the people with whom they worked and socialised, their associates and collaborators, are less familiar, but offer a fascinating insight into the values and aspirations of the age. Courtesy of VisitWorcester Courtesy Worcester was very different from Birmingham as an ecclesiastical centre and county town; nevertheless it was a location for scientific lectures in the West Midlands. Knowledge v Resources Peter Jones is Professor hether the ‘eighteenth-century knowledge economy’ can of French History at the account on its own for the accelerating pace of University of Birmingham. industrialisation in Great Britain as opposed to France, His book, Industrial Enlightenment, has the Low Countries, Silesia or the Rhineland is another recently been published in matter, of course. On the evidence of the West paperback. WMidlands, we need also to allow for the role played by the market. Further Reading Many economic historians would argue that Britain industrialised first, not Peter M. Jones, Industrial because knowledge levels reached a critical threshold, but because energy was Enlightenment: Science, comparatively cheap and skilled labour forbiddingly expensive. To survive in Technology and Culture in the marketplace entrepreneurs had little choice but to innovate with the aid of Birmingham and the West labour-saving machinery, alternative technologies and creative marketing Midlands, 1760-1820 strategies. Manchester University Did Industrial Enlightenment in the West Midlands therefore depend more Press, 2009, 2013). -

Analysis Sheet

‘Dreams of the Future’ Source Analysis Sheet Directions: As you visit each formative area of Jefferson’s youth, select and analyze one source in each area. Complete the analysis sheet for each source you investigate. Then, share your finDings with the rest of your group anD complete the final box. Station 1: Jefferson’s Upbringing in Central Virginia Background: Thomas Jefferson was born at ShaDwell plantation on April 13, 1743. Thomas Jefferson’s father, Peter Jefferson, purchased the plantation in 1736, which was locateD in central Virginia just a few miles to the east of Jefferson’s eventual home, Monticello. The original ShaDwell House was a one-and-a-half story dwelling, which burneD in February 1770. When Jefferson was two or three, he moveD with his family to Tuckahoe in GoochlanD County to the west of RichmonD. Jefferson receiveD his earliest eDucation there and grew up with his three sisters and three cousins. In 1752, the family moveD back to ShaDwell, but Jefferson was sent to study classics anD French with ReverenD William Douglas in Tuckahoe. He lived there for five years, except During the summer. Jefferson’s father DieD in 1757, effectively making Jefferson the man of the house at 14. However, Jefferson’s mother, Jane RanDolph Jefferson, took charge and ran the estate. A year later, in 1758, Jefferson boarDeD with the Reverent James Maury in Albemarle County near ShaDwell, where he learneD Greek and Latin. Jefferson also grew close to his best childhood friend, Dabney Carr. In 1760, Jefferson left central Virginia for Williamsburg to attenD college at William anD Mary.