The Transformation of the US-Based Liberian Diaspora from Hard Power to Soft Power Agents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case of the U.S.-Based Liberian Diaspora Osman

THE PROMISE AND PERILS OF DIASPORA PARTNERSHIPS FOR PEACE: THE CASE OF THE U.S-BASED LIBERIAN DIASPORA OSMAN ANTWI-BOATENG, PH.D. United Arab Emirates University Department of Political Science Al Ain, UAE ABSTRACT In seeking to contribute towards peace-building in Liberia, the U.S-based Liberian Diaspora is building international partnerships with its liberal minded host country, liberal institutions such as the United Nations and Non-Governmental Organizations and private and corporate entities in the host land. There is a convergence of interests between moderate diaspora groups interested in post- conflict peace-building and liberal minded countries and international institutions seeking to promote the liberal peace. The convergence of such multiple actors offers better prospects for effective building in the homeland because collectively, they serve as counter-weights to the parochial foreign policy impulses of each peace-building stakeholder that might be inimical to peace-building. While there are opportunities for the U.S-based Liberian diaspora to forge international partnerships for peace-building, there are challenges that can undermine well intentioned collaborations. These include: logistical challenges in executing transnational projects; self-seeking Diaspora members, divided leadership and poor coordination, and lack of sustainability of international partnerships. KEYWORDS: Liberia, Diaspora, peace-building, Civil War, Africa, Conflict. _______ INTRODUCTION The dominant discourse about the link between Diasporas and conflict has been overwhelmingly negative and this is not without foundation. A seminal work by Collier et al. (1999) at the World Bank made two conclusions. First, the external resources provided by the Diaspora can generate conflict. Second, the Diaspora poses a greater risk for renewed conflict even when conflict has abated. -

Here You Were Born and We Will Talk a Little About Your Family

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR WILLIAM B. MILAM Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: January 29, 2004 Copyright 2018 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in Bisbee, Arizona, July 24, 1936 BA in History, Stanford University 1956-1959 MA in Economics, University of Michigan 1969-1970 Entered the Foreign Service 1962 Martinique, France—Consular Officer 1962-1964 Charles de Gaulle’s Visit Hurricane of 1963 The Murder of Composer Marc Blitzstein Monrovia, Liberia—Economic Officer 1965-1967 Attempting to Compile Trade Statistics Adventure to Timbuktu Washington, DC—Desk Officer 1967-1969 African North West Country Directorate Working on Mali and the Military Coup Studied at the University of Michigan Washington, DC—Desk Officer 1970-1973 The Office of Monetary Affairs Studying Floating Rates London, United Kingdom—Economic Officer 1973-1975 Inflation under the Labor Party The Yom Kippur War Washington, DC—Economic Officer 1975-1977 Fuels and Energy Office The 1970s Energy Crisis The Carter Administration 1 Washington, DC—Deputy Director/Director 1977-1983 Office of Monetary Affairs The Paris Club Problems between Governments and Banks Working with Brazil and the Paris Club Yaoundé, Cameroon—Deputy Chief of Mission 1983-1985 The Oil Fields of Cameroon Army Mutiny and Fighting Around Yaoundé Washington, DC—Deputy Assistant Secretary 1985-1990 International Finance and Development Fighting the Department of Defense on Microchip Manufacturing Dhaka, -

Beyond Numbers: an Assessment of the Liberian Civil Society

1 Beyond Numbers: An Assessment of the Liberian Civil Society A Report on the CIVICUS Civil Society Index 2010 Foreword By: Dr. Amos C. Sawyer Chair; Governance Commission In this report, one will find the unsung story of the challenges and triumphs of an emergent, but fast developing, civil society sector in Liberia. ! AGENDA CIVICUS Civil Society Index Analytical Report for Liberia 2 FOREWORD The concept of civil society gained greater visibility in the discourse on good governance that occurred after the end of the Cold War. Increasingly, international development organisations began to emphasize the importance of good governance as a driver of development, and to recognize civil society as one of the partners and key actors in decision-making good governance processes. Despite the important role that civil society is expected to play in ensuring good governance, there are very few works that provide a helpful understanding of the place of civil society in a theory of governance, or that serve as a practitioner’s guide to promoting this issue. The paucity of literature on civil society in Liberia is even more acute than what one finds in many other countries. Beyond Numbers: An Assessment of the Liberian Civil Society, A Report on the Civil Society Index 2010 is a good start at providing an instrument for appraising the state of civil society in Liberia. It notes objectively the strengths and potential of civil society and also many of civil society’s challenges and shortcomings. Many of these challenges and shortcomings pre-date the 14 years of civil war, just as many of the strengths of civil society today are built upon pre-war accomplishments by the organisations of associational life of pre-war Liberia. -

Liberian Studies Journal

VOLUME 33 2008 Number 2 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL Nation of Nation of Counties of SIERRA -8 N LEONE Liberia Nation of IVORY COAST -6°N ldunuc Nr Geography Ikpartmcnt University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown iew Map Updated: 2003 sew Published by THE LIBERIAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION, INC. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor Cover page was compiled by Dr. William B. Kory, with cartography work by Joe Sernall at the University of Pittsburgh at Johnston- - Geography Department. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor VOLUME 33 2008 Number 2 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL Editor James S. Guseh North Carolina Central University Associate Editor Emmanuel 0. Oritsejafor North Carolina Central University Book Review Editor Emmanuel 0. Oritsejafor North Carolina Central University Editorial Assistant Monica C. Tsotetsi North Carolina Central University EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD: William C. Allen, Virginia State University Warren d' Azevedo, University of Nevada Alpha M. Bah, College of Charleston Lawrence Breitborde, Knox College Christopher Clapham, Lancaster University D. Elwood Dunn, Sewanee-The University of the South Yekutiel Gershoni, Tel Aviv University Thomas Hayden, Society of African Missions Svend E. Holsoe, University of Delaware Sylvia Jacobs, North Carolina Central University James N. J. Kollie, Sr., University of Liberia Coroann Olcorodudu, Rowan College of N. J. Romeo E. Philips, Kalamazoo College Momo K. Rogers, Kpazolu Media Enterprises Henrique F. Tokpa, Cuttington University College LIBERIAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS: Alpha M. Bah, College of Charleston, President Mary Moran, Colgate University, Secretary-Treasurer James S. Guseh, North Carolina Central University, Parliamentarian Yekutiel Gershoni, Tel Aviv University, Past President Timothy A. -

Interconnected Diasporas, Performance, and the Shaping of Liberian Immigrant Identity Yolanda Covington-Ward

Transforming Communities, Recreating Selves: Interconnected Diasporas, Performance, and the Shaping of Liberian Immigrant Identity Yolanda Covington-Ward Africa Today, Volume 60, Number 1, Fall 2013, pp. 28-53 (Article) Published by Indiana University Press For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/at/summary/v060/60.1.covington-ward.html Access provided by University of Pittsburgh (20 Oct 2013 23:16 GMT) What is most important is not the “true” origins of the grand march, but the meaning that Liberians col- lectively give to its practice and import in their every- day lives—which explains how a European dance came to define an African immigrant identity. Transforming Communities, Recreating Selves: Interconnected Diasporas, Performance, and the Shaping of Liberian Immigrant Identity Yolanda Covington-Ward This paper examines the role of European ballroom dances such as the grand march in the shaping of group identity, both in Liberia and for Liberians in the United States. I use participant-observation, interviews, and historical docu- mentation to trace transformations in the grand march from the performance of an exclusive, educated Americo-Liberian elite in the nineteenth century to a more inclusive practice, open to Liberians of all backgrounds who immigrated to the United States in the twentieth century. In both cases of these interconnected diasporas, collective performance is used reflexively, to perform group identity for others, and transformatively, to redefine the group itself. This study sug- gests the need for further attention to performance in studies of ethnic group identity formation. Writing in October 1849 to her former master, John McDonogh, in New Orleans, Henrietta Fuller McDonogh’s letter from St. -

Ethnic Groups and Library of Congress Subject Headings

Ethnic Groups and Library of Congress Subject Headings Jeffre INTRODUCTION tricks for success in doing African studies research3. One of the challenges of studying ethnic Several sections of the article touch on subject head- groups is the abundant and changing terminology as- ings related to African studies. sociated with these groups and their study. This arti- Sanford Berman authored at least two works cle explains the Library of Congress subject headings about Library of Congress subject headings for ethnic (LCSH) that relate to ethnic groups, ethnology, and groups. His contentious 1991 article Things are ethnic diversity and how they are used in libraries. A seldom what they seem: Finding multicultural materi- database that uses a controlled vocabulary, such as als in library catalogs4 describes what he viewed as LCSH, can be invaluable when doing research on LCSH shortcomings at that time that related to ethnic ethnic groups, because it can help searchers conduct groups and to other aspects of multiculturalism. searches that are precise and comprehensive. Interestingly, this article notes an inequity in the use Keyword searching is an ineffective way of of the term God in subject headings. When referring conducting ethnic studies research because so many to the Christian God, there was no qualification by individual ethnic groups are known by so many differ- religion after the term. but for other religions there ent names. Take the Mohawk lndians for example. was. For example the heading God-History of They are also known as the Canienga Indians, the doctrines is a heading for Christian works, and God Caughnawaga Indians, the Kaniakehaka Indians, (Judaism)-History of doctrines for works on Juda- the Mohaqu Indians, the Saint Regis Indians, and ism. -

Cops Collar Suspect After High-Speed Pursuit Officers Continued Following the RECORD-PRESS Plainfield Man Allegedly Drove Directly at Officer Idowu at a Slower Speed

1ft •o raa Serving Westfieid, Scotch Plains and Fanwood Friday, February 3, 2006 50 cents Cops collar suspect after high-speed pursuit officers continued following THE RECORD-PRESS Plainfield man allegedly drove directly at officer Idowu at a slower speed. Police had a minor break WESTFIELD — A Nigerian The chase began around 1 ing towards Scotch Plains. By trol car. Idowu again almost hit a when slow traffic at the intersec- immigrant led officers on a high- p.m. at the intersection of South this time police had realized tractor trailer as he sped onto tion of New Providence Road speed chase through several local Avenue and Crossway Place, Idowu's license plate was not reg- Route 22 eastbound, with police caused Idowu to turn into the towns Friday afternoon, causing according to Sgt. Scott Rodger, istered to his car, but to a blue right behind. parking lot of the Mountainside several accidents in the process whose brother, Officer Jason Mercedes-Benz. As he continued "He was violently changing municipal building. Officer Jason but fortunately avoiding cata- Rodger, attempted to stop Idowu racing past cars — and past lanes and passing cars by strad- Rodger immediately blocked off strophic damage. after he saw the driver almost hit Brunner Elementary School on dling the lanes and driving in the exit, Idowu's only path of Adewale Idowu, 61, of another car. But when the brown Westfieid Road — Idowu nearly between them," said Rodger. escape. Mountainside police got Plainfield was arrested after he Mercedes-Benz did not stop or collided with a Fed Ex truck and Mountainside police were con- out and began walking towards crashed into two cars at slow down, Rodger began pur- was "erratically driving in the tacted and immediately joined Idowu's car after he crashed into Crossway Place. -

Refugees, Rights, and Race: How Legal Status Shapes Liberian Immigrants’ Relationship with the State

Refugees, Rights, and Race: How Legal Status Shapes Liberian Immigrants’ Relationship with the State Dr. Hana E. Brown [email protected] Abstract Drawing on three years of participant-observation in a Liberian immigrant community, this article examines the role of legal refugee status in immigrants’ daily encounters with the state. Using the literature on immigrant incorporation, claims-making, and citizenship, it argues that refugee status profoundly shapes individuals’ views and expectations of their host government as well as their interactions with the medical, educational, and social service institutions they encounter. The refugees in this study use their refugee status to make claims for legal and social citizenship and to distance themselves from native-born Blacks. In doing so, they validate their own position vis-à- vis the state and in the American ethno-racial hierarchy. The findings presented demonstrate how refugee status operates as a symbolic and interpretive resource used to negotiate the structural realities of the welfare state and American race relations. These results stress the importance of studying immigrant incorporation from a micro perspective and suggest mechanisms for the adaptational advantages for refugees reported in existing research. Keywords: race, immigration, Africa, incorporation, refugee Acknowledgements: For their helpful comments on earlier version of this article the author thanks Irene Bloemraad, Dawne Moon, Sandra Smith, Rachel Best, Jennifer Carlson, Kimberly Hoang, Daniel Laurison, Laura Mangels, Sarah Anne Minkin, and participants in the Berkeley Interdisciplinary Immigration Workshop and Berkeley Sociology Race Workshop. 1 Refugees, Rights, and Race: How Legal Status Shapes Liberian Immigrants’ Relationship to the State The rapid rise in immigration to the United States over the last decades has generated significant scholarly interest in the issue of incorporation, the process by which immigrants adapt to and gain membership in a receiving society. -

KIMMIE WEEKS CHILD RIGHTS HERO NOMINEE Pages 90–109

KIMMIE WEEKS CHILD RIGHTS HERO NOMINEE PAGES 90–109 WHY HAS Kimmie BeeN NOmiNATED? Kimmie Weeks has been nominated for the 2013 World’s Children’s Prize because he has spent over 20 years, since he was ten years old, fighting for the rights of the child, especially for children affected by war. WHILE FLEEING in wartime Liberia, Kimmie almost died of cholera. There and then he pledged to spend his whole life helping disadvantaged children. Kimmie and his friends founded ‘Voice of the Future’ and learned about the rights of the child. When Kimmie was 16 they organised a campaign to disarm the child soldiers in the civil war. This contributed to the liberation of 20,000 child sol- When the war in Liberia begins, Kimmie Weeks is eight years old diers. One year later, Kimmie and flees from his home with his mother. In the refugee camp out- had to flee. He had revealed side the capital city of Monrovia, Kimmie comes close to dying of that the newly elected President cholera after drinking contaminated water. He survives and pledges of Liberia, Charles Taylor, was recruiting child soldiers to the to spend his whole life helping children who are suffering because Liberian army. The President of war. He has kept that promise. tried to have Kimmie killed. As a refugee in the USA, Kimmie “ ut woman, your child continued his work for children is dead. He’s not affected by war, not only in breathing any more,” Liberia but also in other coun- B says a man to Kimmie’s tries, primarily Sierra Leone and mother in the refugee camp. -

4Real School

Experience Leadership, 4REAL School Order Form Fax or Mail this form to 4REAL (address and fax number below) or order online Compassion and Ship To: Invoice To: Name Name Inspiration with Institution Institution Street Street 4REAL SCHOOL City City Province/State Postal Code Country Province/State Postal Code Country Phone # Phone # Email Method of Payment: Company Cheque or Money Order PO# Visa MasterCard Amex Expiry Date Card# Name on Card Description Qty Price Shipping & Handling Items Cost ENGAGING YOUTH GLOBALLY THROUGH ART, MUSIC, CULTURE & DIGITAL MEDIA TO 1 $9 CREATE COMMUNITY & POSITIVE CHANGE 2-4 $12 5-6 $14 7-13 $16 14-25 $20 26-40 $25 41-60 $30 Subtotal Shipping & Handling GST/HST (where applicable) Total 4REAL is a Canadian Productio 4REAL Customer Service 207 West Hastings St., Suite 802 Vancouver, B.C. V6B 1H7 Canada Office: 604-682-7341 Cell: 778-231-8260 Fax: 604-684-3530 Email: [email protected] issues today. 4REAL School: A dynamic global 4REAL Pawnee educational resource that Leader Featured: Crystal Echo Hawk, Native Rights Leader Celebrity Guest: Casey Affleck, Actor engages students through art, Location Featured: Pawnee Reservation, Oklahoma music, culture and digital media. In 4REAL Pawnee, host Sol Guy takes actor Casey Affleck to the Pawnee Nation reservation in Oklahoma to meet Native 4REAL is a documentary series that takes celebrity leader Crystal Echo Hawk and her NVision crew. NVision, a collective of Native men and women, uses hip hop, popular guests on adventures around the world to connect culture, visual and performing arts to create a dialogue with with young leaders who, under extreme circum- youth about ways to realize their vision for leadership and stances, are effecting positive change in their com- success. -

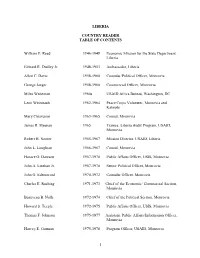

Table of Contents

LIBERIA COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS William E. Reed 1946-1948 Economic Mission for the State Department, Liberia Edward R. Dudley Jr. 1948-1953 Ambassador, Liberia Allen C. Davis 1958-1960 Consular/Political Officer, Monrovia George Jaeger 1958-1960 Commercial Officer, Monrovia Miles Wedeman 1960s USAID Africa Bureau, Washington, DC Leon Weintraub 1962-1964 Peace Corps Volunteer, Monrovia and Kahnple Mary Chiavarini 1963-1965 Consul, Monrovia James R. Meenan 1965 Trainee, Liberia Audit Program, USAID, Monrovia Robert H. Nooter 1965-1967 Mission Director, USAID, Liberia John L. Loughran 1966-1967 Consul, Monrovia Horace G. Dawson 1967-1970 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Monrovia John A. Linehan Jr. 1967-1970 Senior Political Officer, Monrovia John G. Edensword 1970-1972 Consular Officer, Monrovia Charles E. Rushing 1971-1973 Chief of the Economic/ Commercial Section, Monrovia Beauveau B. Nalle 1972-1974 Chief of the Political Section, Monrovia Howard S. Teeple 1972-1975 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Monrovia Thomas F. Johnson 1975-1977 Assistant. Public Affairs/Information Officer, Monrovia Harvey E. Gutman 1975-1978 Program Officer, USAID, Monrovia 1 Beverly Carter, Jr. 1976-1979 Ambassador, Liberia Harold E. Horan 1976-1979 Deputy Chief of Mission, Monrovia Noel Marsh 1976-1980 Program Officer, USAID, Monrovia Julius W. Walker Jr. 1978-1981 Deputy Chief of Mission, Monrovia Parker W. Borg 1979-1981 Country Director, West African Affairs, Washington, DC Robert P. Smith 1979-1981 Ambassador, Liberia Peter David Eicher 1981-1983 Desk Officer, Washington, DC John D. Pielemeier 1981-1984 Deputy Director, USAID, Monrovia John E. Hall 1984-1986 Economic Counselor, Monrovia Keith L. Wauchope 1984-1986 Deputy Director, Francophone West Africa, Washington, DC 1986-1989 Deputy Chief of Mission, Monrovia Herman J. -

Liberia: How Sustainable Is the Recovery?

LIBERIA: HOW SUSTAINABLE IS THE RECOVERY? Africa Report N°177 – 19 August 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. THE ROAD TO ELECTIONS 2011 ................................................................................ 4 A. NEW PARTY MERGERS, SAME OLD POLITICS ............................................................................... 4 B. ELECTORAL PREPARATIONS ......................................................................................................... 6 1. Voter registration ......................................................................................................................... 7 2. Revising electoral districts ........................................................................................................... 8 3. Referendum .................................................................................................................................. 9 C. AN OPEN RACE .......................................................................................................................... 10 D. THE MEDIA ................................................................................................................................ 10 III. SECURITY IN THE SHORT AND MID-TERM ........................................................ 11 A. THE STATE OF THE REFORMED SECURITY SECTOR ....................................................................