Interconnected Diasporas, Performance, and the Shaping of Liberian Immigrant Identity Yolanda Covington-Ward

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case of the U.S.-Based Liberian Diaspora Osman

THE PROMISE AND PERILS OF DIASPORA PARTNERSHIPS FOR PEACE: THE CASE OF THE U.S-BASED LIBERIAN DIASPORA OSMAN ANTWI-BOATENG, PH.D. United Arab Emirates University Department of Political Science Al Ain, UAE ABSTRACT In seeking to contribute towards peace-building in Liberia, the U.S-based Liberian Diaspora is building international partnerships with its liberal minded host country, liberal institutions such as the United Nations and Non-Governmental Organizations and private and corporate entities in the host land. There is a convergence of interests between moderate diaspora groups interested in post- conflict peace-building and liberal minded countries and international institutions seeking to promote the liberal peace. The convergence of such multiple actors offers better prospects for effective building in the homeland because collectively, they serve as counter-weights to the parochial foreign policy impulses of each peace-building stakeholder that might be inimical to peace-building. While there are opportunities for the U.S-based Liberian diaspora to forge international partnerships for peace-building, there are challenges that can undermine well intentioned collaborations. These include: logistical challenges in executing transnational projects; self-seeking Diaspora members, divided leadership and poor coordination, and lack of sustainability of international partnerships. KEYWORDS: Liberia, Diaspora, peace-building, Civil War, Africa, Conflict. _______ INTRODUCTION The dominant discourse about the link between Diasporas and conflict has been overwhelmingly negative and this is not without foundation. A seminal work by Collier et al. (1999) at the World Bank made two conclusions. First, the external resources provided by the Diaspora can generate conflict. Second, the Diaspora poses a greater risk for renewed conflict even when conflict has abated. -

Here You Were Born and We Will Talk a Little About Your Family

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR WILLIAM B. MILAM Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: January 29, 2004 Copyright 2018 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in Bisbee, Arizona, July 24, 1936 BA in History, Stanford University 1956-1959 MA in Economics, University of Michigan 1969-1970 Entered the Foreign Service 1962 Martinique, France—Consular Officer 1962-1964 Charles de Gaulle’s Visit Hurricane of 1963 The Murder of Composer Marc Blitzstein Monrovia, Liberia—Economic Officer 1965-1967 Attempting to Compile Trade Statistics Adventure to Timbuktu Washington, DC—Desk Officer 1967-1969 African North West Country Directorate Working on Mali and the Military Coup Studied at the University of Michigan Washington, DC—Desk Officer 1970-1973 The Office of Monetary Affairs Studying Floating Rates London, United Kingdom—Economic Officer 1973-1975 Inflation under the Labor Party The Yom Kippur War Washington, DC—Economic Officer 1975-1977 Fuels and Energy Office The 1970s Energy Crisis The Carter Administration 1 Washington, DC—Deputy Director/Director 1977-1983 Office of Monetary Affairs The Paris Club Problems between Governments and Banks Working with Brazil and the Paris Club Yaoundé, Cameroon—Deputy Chief of Mission 1983-1985 The Oil Fields of Cameroon Army Mutiny and Fighting Around Yaoundé Washington, DC—Deputy Assistant Secretary 1985-1990 International Finance and Development Fighting the Department of Defense on Microchip Manufacturing Dhaka, -

Liberian Studies Journal

VOLUME 33 2008 Number 2 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL Nation of Nation of Counties of SIERRA -8 N LEONE Liberia Nation of IVORY COAST -6°N ldunuc Nr Geography Ikpartmcnt University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown iew Map Updated: 2003 sew Published by THE LIBERIAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION, INC. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor Cover page was compiled by Dr. William B. Kory, with cartography work by Joe Sernall at the University of Pittsburgh at Johnston- - Geography Department. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor VOLUME 33 2008 Number 2 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL Editor James S. Guseh North Carolina Central University Associate Editor Emmanuel 0. Oritsejafor North Carolina Central University Book Review Editor Emmanuel 0. Oritsejafor North Carolina Central University Editorial Assistant Monica C. Tsotetsi North Carolina Central University EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD: William C. Allen, Virginia State University Warren d' Azevedo, University of Nevada Alpha M. Bah, College of Charleston Lawrence Breitborde, Knox College Christopher Clapham, Lancaster University D. Elwood Dunn, Sewanee-The University of the South Yekutiel Gershoni, Tel Aviv University Thomas Hayden, Society of African Missions Svend E. Holsoe, University of Delaware Sylvia Jacobs, North Carolina Central University James N. J. Kollie, Sr., University of Liberia Coroann Olcorodudu, Rowan College of N. J. Romeo E. Philips, Kalamazoo College Momo K. Rogers, Kpazolu Media Enterprises Henrique F. Tokpa, Cuttington University College LIBERIAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS: Alpha M. Bah, College of Charleston, President Mary Moran, Colgate University, Secretary-Treasurer James S. Guseh, North Carolina Central University, Parliamentarian Yekutiel Gershoni, Tel Aviv University, Past President Timothy A. -

Ethnic Groups and Library of Congress Subject Headings

Ethnic Groups and Library of Congress Subject Headings Jeffre INTRODUCTION tricks for success in doing African studies research3. One of the challenges of studying ethnic Several sections of the article touch on subject head- groups is the abundant and changing terminology as- ings related to African studies. sociated with these groups and their study. This arti- Sanford Berman authored at least two works cle explains the Library of Congress subject headings about Library of Congress subject headings for ethnic (LCSH) that relate to ethnic groups, ethnology, and groups. His contentious 1991 article Things are ethnic diversity and how they are used in libraries. A seldom what they seem: Finding multicultural materi- database that uses a controlled vocabulary, such as als in library catalogs4 describes what he viewed as LCSH, can be invaluable when doing research on LCSH shortcomings at that time that related to ethnic ethnic groups, because it can help searchers conduct groups and to other aspects of multiculturalism. searches that are precise and comprehensive. Interestingly, this article notes an inequity in the use Keyword searching is an ineffective way of of the term God in subject headings. When referring conducting ethnic studies research because so many to the Christian God, there was no qualification by individual ethnic groups are known by so many differ- religion after the term. but for other religions there ent names. Take the Mohawk lndians for example. was. For example the heading God-History of They are also known as the Canienga Indians, the doctrines is a heading for Christian works, and God Caughnawaga Indians, the Kaniakehaka Indians, (Judaism)-History of doctrines for works on Juda- the Mohaqu Indians, the Saint Regis Indians, and ism. -

Refugees, Rights, and Race: How Legal Status Shapes Liberian Immigrants’ Relationship with the State

Refugees, Rights, and Race: How Legal Status Shapes Liberian Immigrants’ Relationship with the State Dr. Hana E. Brown [email protected] Abstract Drawing on three years of participant-observation in a Liberian immigrant community, this article examines the role of legal refugee status in immigrants’ daily encounters with the state. Using the literature on immigrant incorporation, claims-making, and citizenship, it argues that refugee status profoundly shapes individuals’ views and expectations of their host government as well as their interactions with the medical, educational, and social service institutions they encounter. The refugees in this study use their refugee status to make claims for legal and social citizenship and to distance themselves from native-born Blacks. In doing so, they validate their own position vis-à- vis the state and in the American ethno-racial hierarchy. The findings presented demonstrate how refugee status operates as a symbolic and interpretive resource used to negotiate the structural realities of the welfare state and American race relations. These results stress the importance of studying immigrant incorporation from a micro perspective and suggest mechanisms for the adaptational advantages for refugees reported in existing research. Keywords: race, immigration, Africa, incorporation, refugee Acknowledgements: For their helpful comments on earlier version of this article the author thanks Irene Bloemraad, Dawne Moon, Sandra Smith, Rachel Best, Jennifer Carlson, Kimberly Hoang, Daniel Laurison, Laura Mangels, Sarah Anne Minkin, and participants in the Berkeley Interdisciplinary Immigration Workshop and Berkeley Sociology Race Workshop. 1 Refugees, Rights, and Race: How Legal Status Shapes Liberian Immigrants’ Relationship to the State The rapid rise in immigration to the United States over the last decades has generated significant scholarly interest in the issue of incorporation, the process by which immigrants adapt to and gain membership in a receiving society. -

The Transformation of the US-Based Liberian Diaspora from Hard Power to Soft Power Agents

African Studies Quarterly | Volume 13, Issues 1 & 2| Spring 2012 The Transformation of the US-Based Liberian Diaspora from Hard Power to Soft Power Agents OSMAN ANTWI-BOATENG Abstract: As a result of a “hurting stalemate” and the failure to capture power through coercion, moderate elements within the US-based Liberian diaspora resorted to soft power in order to have a greater impact on homeland affairs. The effectiveness of the diaspora is aided by the attractiveness of diaspora success and US culture, the morality of diaspora policies, and the credibility and legitimacy of the diaspora. The US-based Liberian diaspora exerts soft power influences towards peace building via the following mechanisms: persuasion and dialogue; public diplomacy; media assistance; and development assistance/job creation campaigns. The study concludes that development assistance/job creation campaigns are the least sustainable because of cost compared to the other mechanisms that attract a buy-in from the community. This research is based on snowball and in-depth interviews with forty US-based Liberian diaspora leaders that also includes leaders of non-Liberian advocacy groups and participatory observation of selected diaspora activities from 2007-2010. It is also supplemented with content analysis of US-based Liberian diaspora online discussion forums and archival records of congressional hearings on Liberia during the civil war. Introduction The emergent literature on diasporas and conflict as captured by Eva Ostergaard-Nielsen (2006); Hazel Smith and Paul Stares (2007); Feargal Cochrane (2007); Terrence Lyons (2004), and Camilla Orjuela (2008) points to contentious politics and the exercise of hard power which tends to generate conflict in the homeland. -

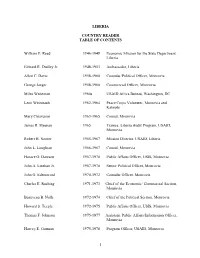

Table of Contents

LIBERIA COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS William E. Reed 1946-1948 Economic Mission for the State Department, Liberia Edward R. Dudley Jr. 1948-1953 Ambassador, Liberia Allen C. Davis 1958-1960 Consular/Political Officer, Monrovia George Jaeger 1958-1960 Commercial Officer, Monrovia Miles Wedeman 1960s USAID Africa Bureau, Washington, DC Leon Weintraub 1962-1964 Peace Corps Volunteer, Monrovia and Kahnple Mary Chiavarini 1963-1965 Consul, Monrovia James R. Meenan 1965 Trainee, Liberia Audit Program, USAID, Monrovia Robert H. Nooter 1965-1967 Mission Director, USAID, Liberia John L. Loughran 1966-1967 Consul, Monrovia Horace G. Dawson 1967-1970 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Monrovia John A. Linehan Jr. 1967-1970 Senior Political Officer, Monrovia John G. Edensword 1970-1972 Consular Officer, Monrovia Charles E. Rushing 1971-1973 Chief of the Economic/ Commercial Section, Monrovia Beauveau B. Nalle 1972-1974 Chief of the Political Section, Monrovia Howard S. Teeple 1972-1975 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Monrovia Thomas F. Johnson 1975-1977 Assistant. Public Affairs/Information Officer, Monrovia Harvey E. Gutman 1975-1978 Program Officer, USAID, Monrovia 1 Beverly Carter, Jr. 1976-1979 Ambassador, Liberia Harold E. Horan 1976-1979 Deputy Chief of Mission, Monrovia Noel Marsh 1976-1980 Program Officer, USAID, Monrovia Julius W. Walker Jr. 1978-1981 Deputy Chief of Mission, Monrovia Parker W. Borg 1979-1981 Country Director, West African Affairs, Washington, DC Robert P. Smith 1979-1981 Ambassador, Liberia Peter David Eicher 1981-1983 Desk Officer, Washington, DC John D. Pielemeier 1981-1984 Deputy Director, USAID, Monrovia John E. Hall 1984-1986 Economic Counselor, Monrovia Keith L. Wauchope 1984-1986 Deputy Director, Francophone West Africa, Washington, DC 1986-1989 Deputy Chief of Mission, Monrovia Herman J. -

STATE of MINNESOTA ,,,N

STATE OF MINNESOTA Office of Governor Mark Dayton 130 State Capitol • 75 Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard • Saint Paul, MN 55155 March 27, 2018 ~ (f) The Honorable Donald J. Trump CD- ("') 3 a,> President of the United States > :::0 -<I 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW "-> l'T! f'Tl )<0 Washington, DC 20500 '° l"'l' x,. (I)o ,.,,::o ::z ,,,n \0 C'") ~ .. < Dear President Trump: ~ ,,, c.n 0 I write to urge you to reconsider your decision to tenninate Deferred Enforced Departure (DED) for Liberian Americans, reinstate Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for immigrants in our communities, and find a pennanent pathway to citizenship for "Dreamers," many of whom have lived in and contributed to the United States for most of their lives. Given your recent decision, on March 3 1•', 2019, thousands of Liberian Americans could be removed from the United States ifDED is not renewed. I ask that you reconsider this decision to terminate the program. Many Liberian OED holders have been in the United. States for over 30 years and have built families and careers in our country. They are part of the social fabric of Minnesota; they are our neighbors, colleagues, and friends. In 1989, a devastating civil war began in Liberia which ravaged that country for seven years, and displaced millions. Liberia is still recovering from that conflict, and so are its people. Many fled to find new lives for themselves and their families - including thousands who settled here in the United States. Minnesotans welcomed Liberian refugees with open arms, and today our state is home to the largest community of Liberian Americans of any state in the nation. -

African Communities Together; Undocublack Network; David Kroma; Momulu Bongay; Othello A.S.C

Case: 19-2122 Document: 00117520422 Page: 1 Date Filed: 11/26/2019 Entry ID: 6300198 No. 19-2122 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIRST CIRCUIT _____________________________________________________ AFRICAN COMMUNITIES TOGETHER; UNDOCUBLACK NETWORK; DAVID KROMA; MOMULU BONGAY; OTHELLO A.S.C. DENNIS; YATTA KIAZOLU; CHRISTINA WILSON; JERRYDEAN SIMPSON; C.B., by and through their father and next friend David Kroma; AL. K, by and through their father and next friend David Kroma; D.D., by and through their father and next friend David Kroma; AI. K, by and through their father and next friend David Kroma; AD. K., by and through their father and next friend David Kroma; O.D., by and through their father and next friend Othello A.S.C. Dennis; A.D., by and through their father and next friend Othello A.S.C. Dennis; O.S., by and through their father and next friend Jerrydean Simpson; D.K., by and through their father and next friend David Kroma, Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. DONALD J. TRUMP, in his official capacity as President of the United States; CHAD WOLF, in his official capacity as acting Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, Defendants-Appellees. _____________________________________________________ ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS _____________________________________________________ BRIEF FOR MINNESOTA, MASSACHUSETTS, CALIFORNIA, CONNECTICUT, DELAWARE, ILLINOIS, MARYLAND, NEVADA, NEW JERSEY, NEW YORK, RHODE ISLAND, VIRGINIA, WASHINGTON, AND THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS _____________________________________________________ Case: 19-2122 Document: 00117520422 Page: 2 Date Filed: 11/26/2019 Entry ID: 6300198 KEITH ELLISON Attorney General State of Minnesota Liz Kramer Solicitor General Jason Marisam, 1st Cir. -

Interview with Ambassador Keith L. Wauchope

Library of Congress Interview with Ambassador Keith L. Wauchope Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR KEITH L. WAUCHOPE Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: March 8, 2002 Copyright 2007 ADST Q: Today is March 8th, 2002. This is an interview with Keith Wauchope. This is done on behalf of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training and I'm Charles Stuart Kennedy. Keith, let's start kind of at the beginning. Could you tell me when and where you were born? WAUCHOPE: I was born at Manhattan Hospital in New York City on October 13, 1941. My parents actually lived out on the south shore of Long Island at the time Q: Okay, tell me a bit about, first of all on your father's side, sort of where the family came from and your father's education and what he was doing. WAUCHOPE: Okay, well, my father's father came to the United States in the early 1880s. He was a young man in County Cavan, Ireland and was sent by his father down to Trinity College Dublin to study for the ministry, the Presbyterian ministry. He and his older brother Jack, who was also studying at Trinity, decided they didn't want to become ministers, so they quite literally ran away to sea. He and his brother first went off to Australia and this trade between the UK, between England and Australia. After several voyages in the 1870s my grandfather jumped ship and joined the Australian army. I was told and that he stayed in Australia for only about six months or so, and then deserted the army and signed onto Interview with Ambassador Keith L. -

Academy for Educational Development

IN AFRICA ACADEMY FOR EDUCATIONAL DEVELOPMENT www.aed.org Inside Benin ......................................5 Botswana ................................7 Djibouti ................................10 Eritrea ..................................12 Ethiopia ................................14 Ghana ..................................19 Guinea ..................................26 Kenya ....................................28 Lesotho..................................32 Liberia ..................................34 Madagascar ..........................36 Malawi ..................................37 Mali ......................................43 Morocco ................................46 Namibia ................................50 Niger ....................................55 Nigeria ..................................58 Rwanda ................................61 Senegal ................................62 South Africa ........................64 Tanzania ..............................70 Tunisia ..................................73 Uganda ................................77 Zambia ..................................81 Zimbabwe ............................85 Multicountry Projects ..........90 AED IN AFRICA ACADEMY FOR EDUCATIONAL DEVELOPMENT CAPE VERDE DEM. REP. OF CONGO AED IN AFRICA AED IN AED in Africa ounded in 1961, the Academy for Educational Development (AED) is an independent, nonprofit, charitable organization that operates development programs in the United States and throughout the world. A total of 52 project offices have been established in Africa, -

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR LEONARD SHURTLEFF Interviewed by: Judy Carson Initial interview date: December 28th, 2012 Copyright 2015 ADST [Note: This interview was not edited by Ambassador Shurtleff prior to his death.] Q: This is Judy Carson, Friday, December 28th, 2012. I am interviewing Ambassador Leonard Shurtleff in Florida. OK. Ambassador, thank you for coming to join me in Florida, in Sebring, Florida. And I understand -- where do you live now? SHURTLEFF: Gainesville, Florida. Q: Gainesville, Florida. Fantastic. SHURTLEFF: Right in the middle of the state. Q: In the middle of the state, excellent. Thank you for, for deciding to interview, that’s fantastic. I’ll -- what we’d like to do is start really at the very beginning. Little bit about your family history, where you were born, what your parents did -- SHURTLEFF: OK. Q: -- and your early life, please. SHURTLEFF: OK. The Shurtleffs are from Massachusetts. The first Shurtleffs arrived about 1630, so we’ve been there a long time. Q: Wow. SHURTLEFF: And I grew up in Haverhill, which is just 25 miles north of Boston on the Merrimack River. Went to Haverhill High School, graduating in 1958. Q: You were born when, what year? SHURTLEFF: June 4th, 1940. Q: That’s right. SHURTLEFF: 1958, 18-years-old. 1 Q: Mm-hmm. SHURTLEFF: In high school, I lettered in track and basketball, was a member of the National Arts Society. Q: Wow. SHURTLEFF: My father was a self-employed businessman. He sold tires and automotive accessories. Did quite well at it.