Research on the Aged Society with a Declining Birthrate and a Society Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Implementing English Education Policy in Japan: Intersubjectivity at the Micro-, Meso-, and Macrolevels

Implementing English Education Policy in Japan: Intersubjectivity at the Micro-, Meso-, and Macrolevels Sunao Fukunaga A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: Sandra Silberstein, Chair Suhanthie Motha James Tollefson Program Authorized to Offer Degree: English © Copyright 2016 Sunao Fukunaga University of Washington Abstract Implementing English Education Policy in Japan: Intersubjectivity at the Micro-, Meso-, and Macrolevels Sunao Fukunaga Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Sandra Silberstein Department of English English education in Japan has been stigmatized by a discourse of failure and desire (Seargeant, 2008). It fails to help students attain sufficient English proficiency despite the six- year secondary school English education. The inferior discourse has condemned teachers’ inability to teach communicative English. Yet, English is desired more than ever for access to new knowledge and the global market. Responding to the situation, the 8th version of national English education policy, the Courses of Study, went into effect in April 2013, proclaiming English as a medium of instruction in senior high school English classes. Research (Hashimoto, 2009; Kawai, 2007) finds the conflation of contesting ideologies make the macro-level policy not as straightforward as it sounds. An overt goal is to improve students’ intercultural communicative competence; another covert goal is to promote to the world what Japan as a nation is and its citizens’ ethnic and cultural identity in English (Hashimoto, 2013). Although studies elucidated the ideologies inscribed in the policy, few have examined teachers’ lives: the agents implementing the language policy at the micro-level. -

Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology - Japan

From MEXT to the NEXT Overview of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology - Japan https://www.mext.go.jp/ MEXT is the acronym of “Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology” taken from its abbreviation MECSST. MEXT MINISTRY OF EDUCATION, CULTURE, SPORTS, SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY-JAPAN 3-2-2 Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-8959, Japan TEL: +81-3-5253-4111 [Issued March, 2021] INDEX Organization of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and 4 Technology (MEXT) Chronology of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) Introduction of the Bureaus 6 Education Policy Bureau ● EDUCATION 8 Elementary and Secondary Education Bureau ● EDUCATION 12 Higher Education Bureau ● EDUCATION 14 Science and Technology Policy Bureau ● SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY 16 Research Promotion Bureau ● SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY 18 Research and Development Bureau ● SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY 20 Japan Sports Agency ● SPORTS 22 Agency for Cultural Affairs ● CULTURE 24 Minister’s Secretariat / Director-General for International Affairs 25 Department of Facilities Planning and Disaster Prevention 26 Statistics 30 Introduction of Related Independent Administrative Institutions 31 Map and Directory 02 Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology EDUCATION SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY SPORTS CULTURE Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology 03 Minister Parliamentary Vice- Special Advisor to the Secretary to the State Ministers (2) Ministers (2) Minister Minister (Administrative) -

August 20, 2012

August 20, 2012 Prepared: NGO Network for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (ERD Net) Submitted: The International Movement Against All Forms of Discrimination and Racism – Japan Committee – IMADR-JC To the CERD Secretariat: We are pleased to submit the report concerning the hate speech against minority communities in Japan hoping that this could contribute to the CERD thematic discussion on hate speech of August 30, 2012. The report covers the propaganda of hate speech and dissemination of derogatory messages against some minority communities in Japan, namely Buraku, Zainichi Koreans and migrants. The present report does not cover the other minority communities such as Ryukyu-Okinawans and the Ainu, but we believe that a similar manifestation would be demonstrated against them when they face the challenge of hate speech. When we discuss about the hate speech in Japan, it is nothing but only a problem under no control. The main reasons rest with the absence of criminal code that prohibits and sanctions racist hate speech. Unless a committed hate speech has some connections or implications to other crimes, there is no legal means that forces an immediate halt of such act. Hate speech could constitute an illegal act under the civil law and only when it is aimed at specific individuals. As indicated in several cases contained in this report, perpetrators of hate speech have been arrested, charged and convicted for the crimes of defamation, forgery of private documents, damage to property, and etc. that are not intended to sanction hate speech. Racially motivated acts are only sanctioned as petty crimes under the present law in Japan, thus, conviction of such acts is less effective in terms of prevention of crimes. -

Historic Factors Influencing Korean Higher Education. Korean Studies Series, No

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 446 656 HE 033 508 AUTHOR Jeong-kyu, Lee TITLE Historic Factors Influencing Korean Higher Education. Korean Studies Series, No. 17. ISBN ISBN-0-9705481-1-7 PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 232p. AVAILABLE FROM Jimoondang International, 575 Easton Ave., 10G Somerset, NJ 08873. PUB TYPE Books (010) Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Asian History; Buddhism; Christianity; Confucianism; Educational Administration; Foreign Countries; *Higher Education; Instructional Leadership; Korean Culture; *Modernism; *School Culture; *Traditionalism IDENTIFIERS *Korea; *Organizational Structure ABSTRACT This book examines the religious and philosophical factors historically affecting Korean higher education, and the characteristics of contemporary Korean higher education in relation to organizational structure, leadership, and organizational cultUre-. The book-is organized into 4 parts,- with 11 chapters. Part One focuses on identifying the problem with Chapter 1 describing the problem, research questions, significance and limitations of the study, definitions of terms, and research methods and procedures. Part Two illustrates the historical background of the study: the traditional period (57 BC-1910 AD) and the modern era (1910-1990s). Chapter 2 introduces the context of Korean higher education in the traditional era, and Chapter 3 illustrates the background of Korean higher education in the modern period. Part Three explores the religious and philosophical factors historically influencing Korean higher education from the perspectives of organizational structure, leadership, and organizational culture. Chapter 4 examines Buddhism in the traditional period, Chapter 5 focuses on Confucianism, and Chapter 6 illustrates Christianity and Western thoughts. Chapter 7 discusses Japanese imperialism under Japanese colonial rule, Chapter 8 shifts thefocus to Americanism under the U.S. -

Ministry of Education Culture Sports Science and Technology Pamphlet

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, 2-5-1 Marunouchi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-8959 Tel: 03-5253-4111 Science and Technology From MEXT we get NEXT MEXT is the acronym of “Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology” taken from the its abbreviation MECSST. CONTENTS Chronology of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) 4 Organization of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) 5 Introduction of the Bureaus 6 6 Lifelong Learning Policy Bureau 8 Elementary and Secondary Education Bureau 10 Higher Education Bureau 12 Science and Technology Policy Bureau 14 Research Promotion Bureau 16 Research and Development Bureau 18 Sports and Youth Bureau 20 Agency for Cultural Affairs 22 Minister’s Secretariat/Director-General for International Affairs Department of Facilities 23 Planning and Administration Statistics 24 Introduction of Related Independent Administrative Institutions 26 Floor Directory and Access Map 27 2 Education Science and Technology Sports Culture 3 Chronology of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) 1871 Ministry of Education established 1872 Promulgation of the school system 1947 The Fundamental Law of Education, School Education Law enacted 1949 Scientific Technical Administration Committee established Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties enacted, and Protection of Cultural Properties Committee 1950 established (external bureau of the Ministry -

Ed 320 488 Author Title Spons Agency Report No Pub Date Available from Pub Type Edrs Price Descriptors Identifiers Abstract Docu

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 320 488 HE 023 571 AUTHOR Chambers, Gail S.; Cummings, William 1:. TITLE Profiting from Education. Japan-United States International Educational Ventures in the 1980s. IIE Research Report Number Twenty. INSTITUTION Institute of International Education, New York, N.Y SPONS AGENCY Japan U.S. Friendship Commission, Washington, D.C.; United States-Japan Foundation. REPORT NO ISBN-87206-183-3 PUB DATE 90 NJTE 180p. AVAILABLE FROM Institute of International Education, 809 United Nations Plaza, New York, NY 10017-3580 ($4.00). PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Academic Standards; Accreditation (Institutions); Financial Support; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *International Cooperation; *International Educational Exchange; Program Development; Resource Allocation; *Student Exchange Programs IDENTIFIERS *Japan; *United States ABSTRACT The Institute of International Educe'ion outlines the forces behind the new wave of intern "tional cooperative venturesin higher education and the challenges they pose through a systematic focus on the Japan-United States transactions. Focus is placedon two prototypes: (1) U.S. accredited institutions setting up a cooperative venture in Japan to offer U.S. accredited courses, and (2) Japanese institutions setting up either a cooperative venture or an autonomous institution in t'ie United States to offer courses that Will receive credit in Japan. Cliapter 1 describes differences in beliefs whichcan lead to reactions of dismay and resistance for these new cooperative ventures. Chapte°. 2, in tracing the evolution of the new ventures, points to their positive elements as well. Chapter 3 discussessome of the typical problems that emerge during negotiations. Chapter 4 examines the performance to date of these institutions in realizing their educational objectives. -

Racial Discrimination in Japan

Joint NGO Report for the Human Rights Committee in response to the List of Issues Prior to Reporting CCPR/C/JP/QPR/7 <PART 2> submitted by Japan NGO Network for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (ERD Net) November 2020 Japan NGO Network for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (ERD Net) is a network of NGOs working for the elimination of racial discrimination in Japan. Since the launch of networking in 2007, it has continually intervened the review of human rights situations of Japan by the HR Committee, CERD and other UN human rights mechanisms. Contact: International Movement Against All Forms of Discrimination and Racism (IMADR) [email protected] NGOs contributing to the Report The International Movement Against All Forms of Discrimination and Racism (IMADR) Japan Network towards Human Rights Legislation for Non-Japanese Nationals & Ethnic Minorities Solidarity Network with Migrants Japan (SMJ) Human Rights Association for Korean Residents in Japan Research-Action Institute for Ethnic Korean Residents (RAIK) Korea NGO Center Center for Minority Issues and Mission Buraku Liberation League (BLL) Association of Indigenous Peoples in the Ryukyus (AIPR) All Okinawa Council for Human Right (AOCHR) JNATIP Japan Network Against Trafficking In Persons Japan Lawyers Network for Refugees Kanagawa MINTOREN Yokohama City Liaison Committee for Abolition of the Nationality Clause Hyogo Association for Human Rights of Foreign Residents National Network for the Total Abolition of the Pension Citizenship Clause (in random order) 1 Joint NGO -

Author Abstract

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 275 620 SO 017 832 AUTHOR Leestma, Robert; Bennett, William J.; And Others TITLE Japanese Education Today. A Report from the U.S. Study of Education in Japan. Prepared by a Special Task Force of the OERI Japan Study Team: Robert Leestma, Director.., and with an epilogue, "Implications for American Education," by William J. Bennett, Secretary of Education. INSTITUTION Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE Jan 87 NOTE 103p.; Other Task Force members: Robert L. August, Betty George, Lois Peak. Other contributors: Nobuo Shimahara, William K. Cummings, Nevner G. Stacey. Editor: Cynthia Hearn Dorfman. For related documents, see SO 017 443-460. PUB TYPE Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Asian Studies; Comparative Education; Educetion; Educational Change; *Elementary School Curriculum; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; *Japanese; *Secondary School Curriculum; Teacher Education IDENTIFIERS *Japan ABSTRACT Based on 2 years of research, this comprehensive report of education in Japan is matched by a simultaneously-released counterpart Japanese study of education in the United States. Impressive accomplishments of the Japanese systemare described. For example, nearly everyone completes a rigorouscore curriculum during 9 compulsory years of schooling, about 90 percent of the students graduate from high school, academic achievement tends to be high, and schools contribute substantially to national economic strength. Reasons for Japanese successes include: clear purposes rooted deeply in the culture, well-defined and challenging curricula, well-ordered learning environments, high expectations for student achievement, strong motivation and effective study habits of students, extensive family involvement in the mission of schools, and highstatus of teachers. -

And Junior Colleges

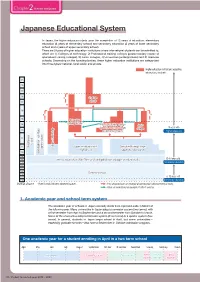

Chapter2 Schools and Exams Japanese Educational System 2. Admission eligibility In principle, you must have completed 12 years of education to apply for admission to a In Japan, the higher education starts upon the completion of 12 years of education: elementary university (undergraduate), junior college, or professional training college in Japan. You education (6 years of elementary school) and secondary education (3 years of lower secondary must have completed 11 years of education to apply for admission to a college of school and 3 years of upper secondary school). technology, and 16 years of education for admission to a graduate school (master’s There are 5 types of higher education institutions where international students can be admitted to, program). which are 1) Colleges of technology, 2) Professional training colleges (postsecondary course of specialized training colleges), 3) Junior colleges, 4) Universities (undergraduate) and 5) Graduate schools. Depending on the founding bodies, these higher education institutions are categorized into three types: national, local public and private. Students from countries such as India, Nepal, Bangladesh, 1) Have completed 12 years of formal school education by taking an additional one Higher education institutions accepting Malaysia, Myanmar, Mongolia and Peru who have completed or two years of schooling at a university or other higher education institution or a university preparatory program in their home country. international students 10 or 11 years of elementary and secondary school education 2) Have completed university preparatory courses (junbi kyouiku katei) authorized by and wish to apply for admission to higher education the Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan1 21 institutions, such as universities, in Japan must meet either of (provided, however, that they have completed a level of education equivalent to a the eligibility criteria at right: Japanese high school). -

Human Rights Situation of Korean Residents in Japan with Relate to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

NGO Information for the Human Rights Committee, 121st session: List of Issues Prior to Reporting, Japan 24 July 2017 Human rights situation of Korean residents in Japan with relate to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights ―― rights to education of minority children (arts. 26 and 27), discrimination against some of Koreans in the National Pension Fund (Art.26), Issues on Hate Speech (arts. 2 and 20(2)), right to leave and enter one’s living country (arts. 2,12 and 26), the concept of minorities (arts. 26 and 27) Human Rights Association for Korean Residents in Japan (HURAK) Submitted by: * Human Rights Association for Korean Residents in Japan (HURAK) is a non-profit, non-governmental human rights organization devoted to advocating rights of Korean residents in Japan and contributing to their well-being. HURAK was founded in 1994 by legal experts, researchers and activists in the field of human rights of Korean residents in Japan. HURAK is an affiliated body of the NGO Network for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (ERD Net), which is a nationwide network among NGOs and individuals working for the issues relating to racism, racial discrimination and colonialism in Japan. Website http://k-jinken.net/ E-mail [email protected] Address 3-41-10-3F, Taitou, Taitou-ku, Tokyo, Japan 110-0016 1 Rights to education of minority children (arts. 26 and 27) I. Summary 1. The Committee previously issued recommendations and asked a question about the discriminatory measures against Korean schools by the Japanese government. The issues the Committee has covered were: (a) non-recognition of Korean schools (b) discriminatory measures with regard to tax exemption (c) non-recognition of diplomas from Korean schools as direct university entrance qualifications (d) exclusion of Korean school students from the Tuition Waiver Program for high school education (e) discriminatory measures with regard to the provision of subsidies to Korean schools 2. -

Implementation and Impact of the Dual Language IB DP Programme in Japanese Secondary Schools

Implementation and Impact of the Dual Language IB DP Programme in Japanese Secondary Schools Final Report June 16, 2016 Beverley A Yamamoto (ed.) Authors Beverley A Yamamoto Takahiro Saito Maki Shibuya Yukiko Ishikura Adam Gyenes Viktoriya Kim Kim Mawer Chika Kitano 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................................................ 8 KEY RESULTS FROM THE RESEARCH ....................................................................................................... 10 IMPLEMENTATION .................................................................................................................................... 10 ESTABLISHING BASELINE DATA ............................................................................................................... 17 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................................. 20 TABLE 0.2 SCHOOLS OFFERING THE IB DP IN JAPAN BY PREFECTURE AND SCHOOL STATUS AS OF FEBRUARY 2016 ...................................................................................................................................... 22 CHAPTER ONE ...................................................................................................................................... 26 BACKGROUND TO THE IB 200 SCHOOLS PROJECT IN JAPAN ............................................... 26 JAPAN AND INTERNATIONALISATION ..................................................................................................... -

Student Guide to Japan 2017-2018

English 2018-2019 Student Guide to Japan CONTENTS Chapter 1 Japan Facts and Figures .....................................................................1 Why Study in Japan? ...........................................................................2 Learn about Studying in Japan Planning Your Studies in Japan ..........................................................3 Schedule ...............................................................................................4 Chapter 2 Japanese Educational System ............................................................6 Learn about Universities (Undergraduate) and Junior Colleges ............................8 Schools and Exams Graduate Schools .............................................................................. 10 Degree Programs in English ........................................................... 13 Short-term Study Programs and University Transfer Program .... 14 Colleges of Technology ..................................................................... 15 Professional Training Colleges (specialized training colleges postsecondary course) ......................................................................16 Japanese Language Institutes .......................................................... 18 Examination for Japanese University Admission for International Students (EJU) ...................................................................................20 Other Exams Used for Studying in Japan ........................................22 Why I Chose to Study in Japan