A Study on the Development of Cranial Traction Therapy Program for Facial Non-Symmertric Correction -Utilize Delphi Technique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Occipitomastoid Suture As a Novel Landmark to Identify The

The Occipitomastoid Suture as a Novel Landmark to Identify the Occipital Groove and Proximal Segment of the Occipital Artery Halima Tabani MD; Sirin Gandhi MD; Roberto Rodriguez Rubio MD; Michael T. Lawton MD; Arnau Benet M.D. University of California, San Francisco Introduction Results Conclusions The occipital artery (OA) is commonly used as a In 71.5% of the specimens the OA ran in a groove, The OMS is a key landmark for localizing the donor for posterior circulation bypass procedures. while it carved an impression in the rest of the proximal OA. The OMS can be followed inferiorly Localization of OA during harvesting is important to cases (28.5%). In none of the specimens the OA prevent inadvertent damage to the donor. The was found to run in a bony canal. In 68.6% of the from the asterion to the OA groove, thereby proximal portion of the OA is found in the occipital cases, the OMS was found to be medial to the OA localizing the proximal OA. Inadvertent damage to groove. The occipitomastoid suture (OMS) is located groove or impression while in 31.4%, it ran the proximal OA may be avoided by identifying the between the occipital bone and the mastoid portion centrally through the OA groove or impression OMS and dissecting medial to it, since in majority of the temporal bone. This study aimed to assess (Figure 1). The OMS was never found lateral to the of cases, the proximal OA will be located lateral to the relationship between the OMS and the occipital OA it groove, in order to facilitate localization of the proximal portion of OA while harvesting it for bypass Learning Objectives 1.To understand the relationship between the Figure 1 occipital groove and the occiptomastoid suture 2.To understand the potential use of occipitomastoid suture as a landmark to identify the proximal Methods segment of OA in the occipital groove Thirty-five dry skulls were assessed bilaterally (n=70) to study the bony landmarks that can be used to identify and locate the proximal segment of OA. -

Chapter 22 TEMPORAL BONE FRACTURES

Temporal Bone Fractures Chapter 22 TEMPORAL BONE FRACTURES † CARLOS R. ESQUIVEL, MD,* AND NICHOLAS J. SCALZITTI, MD INTRODUCTION INITIAL EVALUATION FRACTURE CLASSIFICATION RADIOGRAPHIC EVALUATION MANAGEMENT OF INJURIES Facial Nerve Injury Hearing Loss Cerebrospinal Fluid Leak and Use of Antibiotic Therapy SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR WARTIME INJURIES Acute Management CASE PRESENTATIONS Case Study 22-1 Case Study 22-2 *Lieutenant Colonel (Retired), Medical Corps, US Air Force; Clinical Director, Department of Defense, Hearing Center of Excellence, Wilford Hall Ambulatory Surgical Center, 59th Medical Wing, Lackland Air Force Base, Texas 78236 †Captain, Medical Corps, US Air Force; Resident Otolaryngologist, San Antonio Military Medical Center, 3551 Roger Brooke Drive, Joint Base San Antonio, Fort Sam Houston, Texas 78234 267 Otolaryngology/Head and Neck Combat Casualty Care INTRODUCTION The conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan have resulted age to the deeper structures of the middle and inner in large numbers of head and neck injuries to NATO ear, as well as the brain. Special arrangement of the (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) and Afghan ser- outer and middle ear is essential for efficient capture vice members. Improvised explosive devices, mortars, and transduction of sound energy to the inner ear in and suicide bombs are the weapons of choice during order for hearing to take place. This efficiency relies this conflict. The resultant injuries are high-velocity on a functional anatomical relationship of a taut tym- projectile injuries. Relatively little is known about the panic membrane connected to a mobile, intact ossicular precise incidence and prevalence of isolated closed chain. Traumatic forces that disrupt this relationship temporal bone fractures in theater. -

Morfofunctional Structure of the Skull

N.L. Svintsytska V.H. Hryn Morfofunctional structure of the skull Study guide Poltava 2016 Ministry of Public Health of Ukraine Public Institution «Central Methodological Office for Higher Medical Education of MPH of Ukraine» Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukranian Medical Stomatological Academy» N.L. Svintsytska, V.H. Hryn Morfofunctional structure of the skull Study guide Poltava 2016 2 LBC 28.706 UDC 611.714/716 S 24 «Recommended by the Ministry of Health of Ukraine as textbook for English- speaking students of higher educational institutions of the MPH of Ukraine» (minutes of the meeting of the Commission for the organization of training and methodical literature for the persons enrolled in higher medical (pharmaceutical) educational establishments of postgraduate education MPH of Ukraine, from 02.06.2016 №2). Letter of the MPH of Ukraine of 11.07.2016 № 08.01-30/17321 Composed by: N.L. Svintsytska, Associate Professor at the Department of Human Anatomy of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy», PhD in Medicine, Associate Professor V.H. Hryn, Associate Professor at the Department of Human Anatomy of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy», PhD in Medicine, Associate Professor This textbook is intended for undergraduate, postgraduate students and continuing education of health care professionals in a variety of clinical disciplines (medicine, pediatrics, dentistry) as it includes the basic concepts of human anatomy of the skull in adults and newborns. Rewiewed by: O.M. Slobodian, Head of the Department of Anatomy, Topographic Anatomy and Operative Surgery of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Bukovinian State Medical University», Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor M.V. -

CASE REPORT Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment to Resolve

CASE REPORT Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment to Resolve Head and Neck Pain After Tooth Extraction Patricia M. Meyer, DO, MS Sharon M. Gustowski, DO, MPH Pain is a common occurrence after tooth extraction and fter dental extraction, the majority of patients have is usually localized to the extraction site. However, clinical Apain lasting less than 1 week that can be controlled experience shows that patients may also have pain in by analgesics. The length, type, and severity of pain vary the head or neck in the weeks after this procedure. The as a result of multiple factors, such as the difficulty of the authors present a case representative of these findings. extraction procedure, the patient’s health status and atti - In the case, cranial and cervical somatic dysfunction in tude, and the patient’s sex. 1 Other pain syndromes that a patient who had undergone tooth extraction was may occur weeks after the procedure—though rare— resolved through the use of osteopathic manipulative include neuropathic pain, temporomandibular disorder, 2,3 treatment. This case emphasizes the need to include a cluster headache, 4,5 and neck and head pain caused by dental history when evaluating head and neck pain as somatic dysfunction. 6,7 Prolonged and nonresolving pain part of comprehensive osteopathic medical care. The should be investigated for such conditions as rheumatologic case can also serve as a foundation for a detailed discus - diseases, tumors, migraine headache, or myofascial pain sion regarding how to effectively incorporate osteopathic syndrome. manipulative treatment into primary care practice for The etiologic characteristics of head and neck pain patients who present with head or neck pain after tooth after dental procedures are multifactorial, depending on extraction. -

Comprehensive Examination of the University of Montana Forensic Case 141

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2005 Comprehensive examination of the University of Montana Forensic Case 141 Amanda Marie Mason The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Mason, Amanda Marie, "Comprehensive examination of the University of Montana Forensic Case 141" (2005). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 9248. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/9248 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRAJRY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature:(^ /^ "7 -^ Œ Æ v Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 A Comprehensive Examination of The University of Montana Forensic Case 141 By Amanda Marie Mason B.A., the University of Evansville Presented in fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Masters of Arts The University of Montana December 2005 Approved by: Committee Chairman Dean, Œ ^uate School I (if -()<r Date UMI Number: EP40050 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Incidence, Number and Topography of Wormian Bones in Greek Adult Dry Skulls K

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Via Medica Journals Folia Morphol. Vol. 78, No. 2, pp. 359–370 DOI: 10.5603/FM.a2018.0078 O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E Copyright © 2019 Via Medica ISSN 0015–5659 journals.viamedica.pl Incidence, number and topography of Wormian bones in Greek adult dry skulls K. Natsis1, M. Piagkou2, N. Lazaridis1, N. Anastasopoulos1, G. Nousios1, G. Piagkos2, M. Loukas3 1Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Health and Sciences, Medical School, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece 2Department of Anatomy, Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece 3Department of Anatomical Sciences, School of Medicine, St. George’s University, Grenada, West Indies [Received: 19 January 2018; Accepted: 7 March 2018] Background: Wormian bones (WBs) are irregularly shaped bones formed from independent ossification centres found along cranial sutures and fontanelles. Their incidence varies among different populations and they constitute an anthropo- logical marker. Precise mechanism of formation is unknown and being under the control of genetic background and environmental factors. The aim of the current study is to investigate the incidence of WBs presence, number and topographical distribution according to gender and side in Greek adult dry skulls. Materials and methods: All sutures and fontanelles of 166 Greek adult dry skulls were examined for the presence, topography and number of WBs. One hundred and nineteen intact and 47 horizontally craniotomised skulls were examined for WBs presence on either side of the cranium, both exocranially and intracranially. Results: One hundred and twenty-four (74.7%) skulls had WBs. -

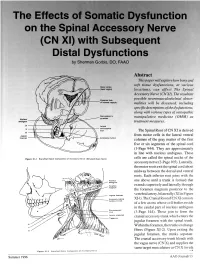

The Effects of Somatic Dysfunction on the Spinal Accessory Nerve (CN XI) with Subsequent Distal Dysfunctions by Sherman Gorbis, DO, FAAO

The Effects of Somatic Dysfunction on the Spinal Accessory Nerve (CN XI) with Subsequent Distal Dysfunctions by Sherman Gorbis, DO, FAAO Abstract This paper will explore how bony and soft tissue dysfunctions, at various Motor codes (head region) locations, can affect The Spinal Accessory Nerve (CN XI). The resultant possible neuromusculoskeletal abnor- Posterior limb of internal capsule malities will be discussed, including specific descriptions of the dysfunctions, along with various types of osteopathic DBOUSSFigon In pyramids manipulative medicine (OMM) as Nucleus amblguus treatment measures. IX Lateral X corticospinal tract The Spinal Root of CN XI is derived XI Jugular from motor cells in the lateral ventral foramen Accessory nucleus columns of the gray matter of the first five or six segments of the spinal cord (1-Page 944). They are approximately in line with nucleus ambiguus. These Flgure XI-I Branchtal Motot Component of Accessory Nerve (Elevated Brain Sterol cells are called the spinal nuclei of the accessory nerve (2-Page 105). Laterally, the motor roots exit the spinal cord about midway between the dorsal and ventral roots. Each inferior root joins with the one above until a trunk is formed that extends superiorly and laterally through the foramen magnum posterior to the Jugular lor•men vertebral artery, bilaterally (XI in Figure Accessory (spinal XI-1). The Cranial Root of CN XI consists nucleus CI-CS of a few axons whose cell bodies reside in the caudal part of nucleus ambiguus Sternomesiod (cull (3-Page 144). These join to form the Lent or scapulae cranial accessory trunk which enters the Trap-axles jugular foramen with the spinal trunk. -

Ectocranial Suture Closure in Pan Troglodytes and Gorilla Gorilla: Pattern and Phylogeny James Cray Jr.,1* Richard S

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 136:394–399 (2008) Ectocranial Suture Closure in Pan troglodytes and Gorilla gorilla: Pattern and Phylogeny James Cray Jr.,1* Richard S. Meindl,2 Chet C. Sherwood,3 and C. Owen Lovejoy2 1Department of Anthropology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15260 2Department of Anthropology and Division of Biomedical Sciences, Kent State University, Kent, OH 44242 3Department of Anthropology, The George Washington University, Washington, DC 20052 KEY WORDS cranial suture; synostosis; variation; phylogeny; Guttman analysis ABSTRACT The order in which ectocranial sutures than either does with G. gorilla, we hypothesized that this undergo fusion displays species-specific variation among phylogenetic relationship would be reflected in the suture primates. However, the precise relationship between suture closure patterns of these three taxa. Results indicated that closure and phylogenetic affinities is poorly understood. In while all three species do share a similar lateral-anterior this study, we used Guttman Scaling to determine if the closure pattern, G. gorilla exhibits a unique vault pattern, modal progression of suture closure differs among Homo which, unlike humans and P. troglodyte s, follows a strong sapiens, Pan troglodytes,andGorilla gorilla.BecauseDNA posterior-to-anterior gradient. P. troglodytes is therefore sequence homologies strongly suggest that P. tr og lodytes more like Homo sapiens in suture synostosis. Am J Phys and Homo sapiens share a more recent common ancestor Anthropol 136:394–399, 2008. VC 2008 Wiley-Liss, Inc. The biological basis of suture synostosis is currently Morriss-Kay et al. (2001) found that maintenance of pro- poorly understood, but appears to be influenced by a liferating osteogenic stem cells at the margins of mem- combination of vascular, hormonal, genetic, mechanical, brane bones forming the coronal suture requires FGF and local factors (see review in Cohen, 1993). -

Atlas of the Facial Nerve and Related Structures

Rhoton Yoshioka Atlas of the Facial Nerve Unique Atlas Opens Window and Related Structures Into Facial Nerve Anatomy… Atlas of the Facial Nerve and Related Structures and Related Nerve Facial of the Atlas “His meticulous methods of anatomical dissection and microsurgical techniques helped transform the primitive specialty of neurosurgery into the magnificent surgical discipline that it is today.”— Nobutaka Yoshioka American Association of Neurological Surgeons. Albert L. Rhoton, Jr. Nobutaka Yoshioka, MD, PhD and Albert L. Rhoton, Jr., MD have created an anatomical atlas of astounding precision. An unparalleled teaching tool, this atlas opens a unique window into the anatomical intricacies of complex facial nerves and related structures. An internationally renowned author, educator, brain anatomist, and neurosurgeon, Dr. Rhoton is regarded by colleagues as one of the fathers of modern microscopic neurosurgery. Dr. Yoshioka, an esteemed craniofacial reconstructive surgeon in Japan, mastered this precise dissection technique while undertaking a fellowship at Dr. Rhoton’s microanatomy lab, writing in the preface that within such precision images lies potential for surgical innovation. Special Features • Exquisite color photographs, prepared from carefully dissected latex injected cadavers, reveal anatomy layer by layer with remarkable detail and clarity • An added highlight, 3-D versions of these extraordinary images, are available online in the Thieme MediaCenter • Major sections include intracranial region and skull, upper facial and midfacial region, and lower facial and posterolateral neck region Organized by region, each layered dissection elucidates specific nerves and structures with pinpoint accuracy, providing the clinician with in-depth anatomical insights. Precise clinical explanations accompany each photograph. In tandem, the images and text provide an excellent foundation for understanding the nerves and structures impacted by neurosurgical-related pathologies as well as other conditions and injuries. -

Model Keys Unit 1

Model Keys This section will supply you with the keys to several of the models found in the anatomy lab and the learning center. This does not include all the models. After the model keys in this section you will find keys to most of the Nystrom charts. In the anatomy lab there is a reference shelve that contains binders with the keys to most models, torsos and the Nystrom charts. Keys to some of the models are actually attached to the model. Chart keys can also be found either right on the chart or posted next to the chart. Unit 1 Numbered Skull (with colored numbers): g. internal occipital crest a. third molar (inside) b. incisive canal h. clivus (inside) c. infraorbital foramen i. foramen magnum d. infraorbital groove j. jugular foramen e. pterygopalatine fossa k. hypoglossal canal 6. Zygomatic bone l. cerebella fossa (inside) a. zygomaticofacial foramen m. vermain fossa (inside) 7. Sphenoid bone 4. Temporal bone a. medial pterygoid plate a. styloid process b. lateral pterygoid plate b. tympanic part c. lesser wing of sphenoid c. mastoid process (inside) d. mastoid notch d. greater wing of sphenoid 1. Frontal bone e. zygomatic process (inside) a. zygomatic process f. articular tubercle e. chiasmatic groove b. frontal crest (inside) g. stylomastoid foramen (inside) c. orbital part (inside) h. mastoid foramen f. anterior clinoid process d. supraorbital foramen i. external acoustic meatus (inside) e. anterior ethmoidal j. internal acoustic meatus g. posterior clinoid process foramen (inside) (inside) f. posterior ethmoidal k. carotid canal h. hypophyseal fossa foramen l. mandibular fossa (inside) g. -

A 3D Stereotactic Atlas of the Adult Human Skull Base Wieslaw L

Nowinski and Thaung Brain Inf. (2018) 5:1 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40708-018-0082-1 Brain Informatics ORIGINAL RESEARCH Open Access A 3D stereotactic atlas of the adult human skull base Wieslaw L. Nowinski1,2* and Thant S. L. Thaung3 Abstract Background: The skull base region is anatomically complex and poses surgical challenges. Although many textbooks describe this region illustrated well with drawings, scans and photographs, a complete, 3D, electronic, interactive, real- istic, fully segmented and labeled, and stereotactic atlas of the skull base has not yet been built. Our goal is to create a 3D electronic atlas of the adult human skull base along with interactive tools for structure manipulation, exploration, and quantifcation. Methods: Multiple in vivo 3/7 T MRI and high-resolution CT scans of the same normal, male head specimen have been acquired. From the scans, by employing dedicated tools and modeling techniques, 3D digital virtual models of the skull, brain, cranial nerves, intra- and extracranial vasculature have earlier been constructed. Integrating these models and developing a browser with dedicated interaction, the skull base atlas has been built. Results: This is the frst, to our best knowledge, truly 3D atlas of the adult human skull base that has been created, which includes a fully parcellated and labeled brain, skull, cranial nerves, and intra- and extracranial vasculature. Conclusion: This atlas is a useful aid in understanding and teaching spatial relationships of the skull base anatomy, a helpful tool to generate teaching materials, and a component of any skull base surgical simulator. Keywords: Skull base, Electronic atlas, Digital models, Skull, Brain, Stereotactic atlas 1 Introduction carotid arteries, among others. -

The Five Diaphragms in Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine: Neurological Relationships, Part 1

Open Access Review Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.8697 The Five Diaphragms in Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine: Neurological Relationships, Part 1 Bruno Bordoni 1 1. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Foundation Don Carlo Gnocchi, Milan, ITA Corresponding author: Bruno Bordoni, [email protected] Abstract In osteopathic manual medicine (OMM), there are several approaches for patient assessment and treatment. One of these is the five diaphragm model (tentorium cerebelli, tongue, thoracic outlet, diaphragm, and pelvic floor), whose foundations are part of another historical model: respiratory-circulatory. The myofascial continuity, anterior and posterior, supports the notion the human body cannot be divided into segments but is a continuum of matter, fluids, and emotions. In this first part, the neurological relationships of the tentorium cerebelli and the lingual muscle complex will be highlighted, underlining the complex interactions and anastomoses, through the most current scientific data and an accurate review of the topic. In the second part, I will describe the neurological relationships of the thoracic outlet, the respiratory diaphragm and the pelvic floor, with clinical reflections. In literature, to my knowledge, it is the first time that the different neurological relationships of these anatomical segments have been discussed, highlighting the constant neurological continuity of the five diaphragms. Categories: Medical Education, Anatomy, Osteopathic Medicine Keywords: diaphragm, osteopathic, fascia, myofascial, fascintegrity,