Of Issionaryresearch Who Dowe Saythathe Isr on the Uniqueness and Uniwrsality of Jesus Christ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Philosophical Investigation of the Nature of God in Igbo Ontology

Open Journal of Philosophy, 2015, 5, 137-151 Published Online March 2015 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojpp http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojpp.2015.52016 A Philosophical Investigation of the Nature of God in Igbo Ontology Celestine Chukwuemeka Mbaegbu Department of Philosophy, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria Email: [email protected] Received 25 February 2015; accepted 3 March 2015; published 4 March 2015 Copyright © 2015 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract In its general task, philosophy as an academic or professional exercise is a conscious, critical, per- sonal reflection on human experience, on man, and how he perceives and interprets his world. This article specifically examines the nature of God in Igbo ontology. It is widely accepted by all philosophers that man in all cultures has the ability to philosophize. This was what Plato and Aris- totle would want us to believe, but it is not the same as saying that man has always philosophized in the academic meaning of the word in the sense of a coherent, systematic inquiry, since power and its use are different things altogether. Using the method of analysis and hermeneutics this ar- ticle sets out to discover, find out the inherent difficulties in the common sense views, ideas and insights of the pre-modern Igbo of Nigeria to redefine, refine and remodel them. The reason is sim- ple: Their concepts and nature of realities especially that of the nature of God were very hazy, in- articulate and confusing. -

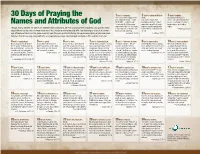

30 Days of Praying the Names and Attributes Of

30 Days of Praying the 1 God is Jehovah. 2 God is Jehovah-M’Kad- 3 God is infinite. The name of the independent, desh. God is beyond measure- self-complete being—“I AM This name means “the ment—we cannot define Him WHO I AM”—only belongs God who sanctifies.” A God by size or amount. He has no Names and Attributes of God to Jehovah God. Our proper separate from all that is evil beginning, no end, and no response to Him is to fall down requires that the people who limits. Though God is infinitely far above our ability to fully understand, He tells us through the Scriptures very specific truths in fear and awe of the One who follow Him be cleansed from —Romans 11:33 about Himself so that we can know what He is like, and be drawn to worship Him. The following is a list of 30 names possesses all authority. all evil. and attributes of God. Use this guide to enrich your time set apart with God by taking one description of Him and medi- —Exodus 3:13-15 —Leviticus 20:7,8 tating on that for one day, along with the accompanying passage. Worship God, focusing on Him and His character. 4 God is omnipotent. 5 God is good. 6 God is love. 7 God is Jehovah-jireh. 8 God is Jehovah-shalom. 9 God is immutable. 10 God is transcendent. This means God is all-power- God is the embodiment of God’s love is so great that He “The God who provides.” Just as “The God of peace.” We are All that God is, He has always We must not think of God ful. -

Names of God and Exodus 3:16

Names of God and Exodus 3:16 Jeffrey D. Oldham 2000 July 15 Starting with Exodus 3:16, we will explore the verse's translation and its context to learn about different names for God. (Start by listing as many different names for God as possible. Possibly transliterate a Hebrew word into the Latin alphabet.) 1 Translating the Verse from Hebrew to English Copying from [GRB43], I have listed a word-for-word translation of Exodus 3:16 from Hebrew to English in Table 1. Hebrew writers can add suf®xes to convert one word into a clause so English words appear next to the Hebrew words in the left column. By choosing among the the choices for each Hebrew word, adding punctuation, and rearranging, write the verse in English. Caveat reader: I obtained the Hebrew transliteration words from both [VeW96, Zod84], which differ in the use of accents and in tone. 2 The Verse's Meaning and Context What does the verse mean? What is its context? Who is the speaker, and who is the listener? What is the verse's context? Question to answer at home: What is the relationship with Gen 50:24±25? What verb is used for God's actions? 3 Names for God What names for God does the verse use? What do each of the different names mean? Why so many different names? What other names are used in Exodus 3? Is there a pattern to their use? c 2000 Jeffrey D. Oldham ([email protected]). All rights reserved. This document may not be redistributed in any form without the express permission of the author. -

Biblical Theology of God (Additional Notes on Character of God; Attributes and Who God Is)

Biblical Theology of God (Additional notes on character of God; attributes and who God is) Compilations from some of the pastors at The Grove Kerry Warren: Attributes of God are simply something that God has revealed about Himself. This can’t be confused with what we attribute to God or what we want God to be. I think for most people how they describe God will reveal what they know about Him. For instance, if they say that He is a spiteful God, then their first impression of Him must be that. I think it will say a lot about people when they are asked to list attributes about God. For me God is truth. He doesn’t lie to me or tell me things that I want to hear. He simply speaks truth even if that truth hurts (Deut. 32:4, Ps 33:4). What God says He will do, He will do. Matt Furby: Scripture Key Phrases Attributes Topic Like the appearance of a rainbow in the Ezekiel 1:13- clouds on a rainy day, so was the radiance Indescribable, glorious Awesome 28 around him Job 11:7-9 Can you fathom the mysteries of God? Indescribable, eternal Awesome Awesome, eternal, and the ancient of days took his seat Awesome, Daniel 9:9-14 unique, over all, sovereign given authority, glory, and sovereign power Eternal over all 1 Corinthians No one knows the thoughts of God except Eternal, far above us Eternal 2:11 the Spirit of God in the beginning Creator/maker John 1:1-5 Eternal made all things Eternal No one has ever seen God, but God the One Unique, eternal, far above John 1:18 Eternal and Only has made him known us from everlasting to everlasting you are God Psalm 90:1-4 Eternal Eternal a thousand years in your sight are like a day Revelation Holy Holy Holy Eternal Eternal 4:8-9 Who was, and is, and is to come I am God, and there is no other God is unique and Isaiah 46:9-13 Eternal what I have planned, that will I do unmatched Even to your old age and gray hairs I am he, I am he who will sustain you Sustains His people, does Eternal, Isaiah 46:3-5 To whom will you compare me or count me not grow old Sovereign equal? Be still and know that I am God. -

The Names of God

The Names of God By Don Fortner © 2010 The Names of God 1 The Names of the Lord Psalm 9:10 “And they that know thy name will put their trust in thee: for thou, LORD, hast not forsaken them that seek thee.” Throughout the Word of God names were given to children that had special meaning and significance. Sometimes a person’ s name would be changed or a name would be ascribed to him, either by God or by someone else, indicating radical change of life. Here are some examples: Adam means “red earth,” indicating his being created by God from the dust of the earth. Jacob means “cheat, supplanter;” but God changed his name to Israel, which means “prince with God.” Moses means “drawn forth.” He was named that because Pharaoh’s daughter drew him out of the water. In the Bible, the name given to a person said something about that person. The same thing is true concerning the names of the Lord our God. However, no single word in human language is sufficient to serve as a name for him. Therefore, there are several words or names by which he has made himself known. The names applied to God in Scripture describe his glorious character, reveal his great attributes, and display his redemptive purpose. In this study we will simply look at the names by which God reveals himself in the Holy Scriptures and their meaning. There are ten specific names ascribed to our God in Holy Scripture. 1. The first revelation of God is found in Genesis 1:1-“In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.” The name of God given there is “ELOHIM.” “Elohim” means “to worship.” This is the name of our God. -

The Names Of

THE NAMES OF GOD Adonai Avinu – The LORD Our Father (Isaiah 64:8) Yahweh Tsidkenu – The Lord Our Righteousness Names for God the Father (Jeremiah 23:5-6) Elohim – The Creator God (Genesis 1:1) Yahweh Shamma – The Lord is There (Ezekiel 48:35) Yahweh – The LORD God (Genesis 2:4) El Elyon – Most High God (Daniel 4:34-35) Adonai El Elyon – The LORD Most High God (Genesis Attiyq Youm – Ancient of Days (Daniel 7:9) 14:22) El-Channun – The Gracious God (Jonah 4:2) Adonai – Lord (Genesis 15:2) Ruler of Israel (Micah 5:2) El Roi – The God Who Sees (Genesis 16:13) El Echad – The One God (Malachi 2:10) El Shaddai – God almighty (Genesis 17:1) Abba – Daddy (Mark 14:36) El Olam – The Everlasting God (Genesis 21:33) Father of Mercies (2 Corinthians 1:3-4) Jehovah-Jireh – The Lord Who Provides (Genesis 22:14) Majesty (Hebrews 8:1) The Shiloh – The Peacemaker (Genesis 49:10) The God of Abraham (Exodus 3:2) Names for Jesus Ehyeh asher Ehyeh – I Am That I Am (Exodus 3:14) Emmanuel – God With Us (Isaiah 7:14) Jehovah-Rapha – The Lord Who Heals (Exodus 15:26) El Gibbor – The Mighty God (Isaiah 9:6) Jehovah-Nissi – The Lord Our Banner (Exodus 17:15) Everlasting Father (Isaiah 9:6) El-Kanno – The Jealous God (Exodus 20:5) Wonderful Counselor (Isaiah 9:6) Adonai Mekaddishkhem – The LORD Your Sanctifier Prince of Peace (Isaiah 9:6) (Exodus 31:13) My Righteous Servant (Isaiah 53:11) Go’el – Kinsman redeemer (Leviticus 25:26) Beloved Son of God (Matthew 3:17) El Rachum – The God Of Compassion (Deuteronomy Bridegroom (Matthew 9:15) 4:31) Son of the Most High (Luke -

The Name of God and the Linguistic Theory of the Kabbala II

Gershom Scholem THE NAME OF GOD AND THE LINGUISTIC THEORY OF THE KABBALA I "Thy word (or: essence) is true from the beginning"; thus reads the Psalmist's passage, oft quoted in kabbalistic literature (Psalm 119: 160). According to the originally conceived Judaistic meaning, truth was the word of God which was audible both acoustically and linguistically.* Under the system of the syna gogue, revelation is an acoustic process, not a visual one; or revelation at least ensues from an area which is metaphysically associated with the acoustic and the perceptible (in a sensual context). This is repeatedly emphasised with reference to the Translated by Simon Pleasance. * This article was originally a lecture given at the Eranos-meeting in Ascona, 1970. 59 The Name of God words of the Torah (Deuteronomy 4: 12): "Ye heard the voice of the words, but saw no similitude; only ye heard a voice." What precisely we are to understand by this voice and what is uttered through it is the very question which the various currents of Judaistic religious thought have constantly posed themselves. The indissoluble link between the idea of the revealed truth and the notion of language—is as much, that is, as the word of God makes itself heard through the medium of human language, if, otherwise, human experience can reach the knowledge of such a word at all—is presumably one of the most important, if not the most important, legacies bequeathed by Judaism to the history of religions. It will not, however, be possible, within the framework made available to us here, to investigate the full breadth and depth of the terms of this question. -

Ghasem Kakaie IBN 'ARABI's GOD, ECKHART's GOD

444 Philosophy of Religion and Kalam * Ghasem Kakaie Ghasem Kakaie (Shiraz University, Iran) IBN ‘ARABI’S GOD, ECKHART’S GOD: GOD OF PHILOSOPHERS OR GOD OF RELIGION? 1. Prelude It is difficult to provide such a definition of God in which all various views are included and all schools agree upon. The dominant view is that Religion’s God is the Origin of the universe and enjoys some kind of transcendence and sacredness. In philosophy, however, there are various images for God: the Gods of ancient Greece, the unmoved mover of Aristotle, the necessary Being of Avicenna, the God of Aquinas’s theism, the God of Spinoza’s the pantheistic, panentheism God in some mystical philosophies, the One in Neoplatonism, the God of process philosophy, the God of existential philosophies, ultimate concern of Tillich, God as the impersonal ground of Being, and aspects of Heidegger’s Dasein are different concepts of deity.1 The God of philosophy is often an object, not a person; something, not some- one, unchangeable, absolute and unlimited. But the God which is worshiped in ordinary religion “is a person and to be a person, an entity must think, feel, and will. In spite of being called unchangeable, he is angry with us today, pleased with us tomorrow.”2 The meaning of God, of course, is to some extent different in the ordinary versions of various religions and even between Abrahamic religions. The God who has no son according to Islam, for example, may differ from the God who has a son as is believed in Christianity. -

Homiletics (HOMI) 1

Homiletics (HOMI) 1 HOMI 895 Directed Research in Homiletics 1-3 Credit Hour(s) HOMILETICS (HOMI) Designed for the advanced student in good standing who has demonstrated an ability to work independently. This course should/can HOMI 810 Preaching and Teaching the Grand Story of the Bible 3 Credit only be used if a student lacks a seminar for graduation and the needed Hour(s) seminar is not offered in their last semester. If approved, the student will Online Prerequisite: DMIN 810 work with the instructor in developing a proposal for guided research in a A study of the principles for accurate interpretation and appropriate specific area. application and delivery of Scripture in its various settings or genres. Offered: Online Problems created by various literary forms, cultural differences, and HOMI 897 Seminar in Homiletics 1-3 Credit Hour(s) theological issues will be considered. Preaching will be engaged with An intensive study in a specific subject of homiletics. This course allows personal examination and employment of forms in light of literary, variation in the approach and content of the regular curriculum and often cultural, and theological issues. will be used by visiting professors. Note: Admission to DMIN program Offered: Online Offered: Online HOMI 820 Expository Preaching and Teaching and the Old Testament 3 Credit Hour(s) Online Prerequisite: DMIN 810 and HOMI 810 This course is designed to prepare students to preach from the Old Testament. Special attention will be given to genres and theological themes that arise from the Old Testament text. Note: Admission to DMIN program Offered: Online HOMI 830 Expository Preaching and Teaching and the New Testament 3 Credit Hour(s) Online Prerequisite: DMIN 810 and HOMI 810 This course is designed to prepare students to preach from the New Testament. -

List of the Names and Titles of God

Participant Handouts for Names and Titles of God 1 List of the Names and Titles of God Here’s a fairly comprehensive list of the names of God grouped according to the chapter classification of names in Names and Titles of God (JesusWalk, 2010), by Dr. Ralph F. Wilson. These names focus primarily on the names of the Father. Names of Jesus will be treated separately. You’ll observe a bit of overlap from one list to another due to differences in translations as well as titles that belong in more than one category. 1. The Exalted God One Who Inhabits Eternity Ancient of Days God (‘El, ‘Elohim) The First and the Last Most High God (‘El ‘Elyon) The Alpha and the Omega Most High Who Is and Who Was Highest and Who Is to Come God of Gods, Lord of lords One Who Lives Forever King of kings Living God High and Lofty One My Glory 4. God our Creator Pride of Jacob Architect King of Glory Builder Father of Glory Builder of All things Glory of Israel/Strength of Israel Builder of Jerusalem Light of Israel Creator 2. The God of Might Creator of heaven and earth Creator of the ends of the earth Almighty God (‘El Shaddai) Israel’s Creator The Almighty (Shaddai) Faithful Creator The LORD of Hosts (Yahweh‐Sabaoth) Father of Lights Commander of the Army of the LORD Former of All Things Man of War (Warrior) God of All the Earth Mighty Warrior (Dread Champion) God of heaven Mighty One of Jacob God of heaven and earth Great and Awesome God King of heaven My Strength Lord of heaven and earth The LORD Our Banner (Yahweh‐nissi) Maker 3. -

Age of Religions

Age of Religions 1. Hinduism , Hinduism is the oldest known spiritual tradition in the world and there is evidence that it flourished long before recorded history in ancient India. The ancient Vedic civilization practiced Hinduism in the Indus Valley over 6,000 years ago and it was already then an old established tradition!!! There is plenty of Evidence that its origin goes back into pre-historic times! Hinduism was developed alreday 6,000 years ago but can be traced back to 5500-2600 BCE 2. Shamanism has its roots in ancient, land-based cultures, dating at least as far back as 40,000 years. The shaman was known as “magician, medicine man, psychopomp, mystic and poet” (Eliade, 1974). 3. Confucianism: ConfucianismThis religion was named after its founder – Confucius (551–479 BC), which has origins in China. Those who embrace this religion, believes that the purpose of life is to fulfill one's role in society with modesty, honor, and loyalty. Some estimates show that there are about 5 to 6 million people following this religion. 4. Buddhism BuddhismThe History of Buddhism spans the 5th century BCE to the present, starting with the birth of Buddha Siddhartha Gautama in Lumbini, Nepal. This makes it one of the oldest religions practiced today. Starting in the north eastern region of the Indian Subcontinent [1], the religion evolved as it spread through Central Asia, East Asia, and Southeast Asia. At one time or another it affected most of the Asian continent. The history of Buddhism is also characterized by the development of numerous movements and schisms among them the Theravāda, Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna traditions, with contrasting periods of expansion and retreat. -

Names of God in Hebrew Bible

www.prshockley.org NAMES OF GOD IN HEBREW BIBLE: www.prshockley.org SHARED BELIEFS: Carefully systematize all the statements, declarations, and inferences In his book, Israelis, Jews and Jesus, regarding the God of the Bible, we come to discover that this infinite and Jewish author, Pinchas Lapide, personal God is the sum-total of His infinite perfections. God is portrayed observes that while significant as personal rather an impersonal, active rather passive towards his differences exist in both belief and dealings with creation, people, and events. practice, Judaism & Christianity share many common beliefs. He Many scholars discuss God’s perfections using a two-fold classification in writes: an effort to better understand how the Judeo-Christian theology of God is We Jews and Christians are joined in disclosed in biblical literature: (1) incommunicable attributes and (2) brotherhood at the deepest level, so communicable attributes. Incommunicable attributes are attributes that deep the fact that we have overlooked it and missed the forest belong to Him alone (e.g., infinity; simplicity) whereas communicable of brotherhood for the trees of attributes are attributes that people may possess in various degrees (e.g., theology. We have an intellectual holiness; justice; love). and spiritual kinship which goes deeper than dogmatics, We also have several others ways to examine and reflect upon the nature hermeneutics, and exegesis. We are of God as understood in Hebrew Bible. For example, we can examine the brothers in a manifold ‘elective affinity’ personhood (e.g., interactive relationships with Israel) by carefully examine the historical context-background with a wide array of tools: - In the belief in one God our Father, archeology, grammar, history, and literary analysis.