Ghasem Kakaie IBN 'ARABI's GOD, ECKHART's GOD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schelling and the Future of God

SSN 1918-7351 Volume 5 (2013) Schelling and the Future of God Jason M. Wirth For Sean McGrath and Andrzej Wiercinski It seems, at least largely among the world’s educated, that Nietzsche’s prognosis of the death of God is coming to pass. Not only is belief in a transcendent being or a grand, supremely real being (ens realissimum) waning, but also the philosophical grounds that made such objects in any way intelligible are collapsing. In such a situation, despite the recent and quite scintillating renaissance of serious interest in Schelling’s philosophy, his various discourses on the Godhead (die Gottheit) are generally ignored, perhaps with mild embarrassment. For better or worse, however, what Schelling understood by the Godhead and even by religion has little in common with prevailing theistic traditions. Schelling did not take advantage of the great ontological lacuna that opened up with the demise of dogmatism in critical philosophy after Kant to insist on an irrational belief in a God that was no longer subject to rational demonstration. Schelling eschews all dogmatic thought, but does not therefore partake in its alternative: the reduction of all thought regarding the absolute to irrational beliefs in (or rational gambles on) the existence of God and other such absolutes. As Quentin Meillassoux has shown, “by forbidding reason any claim to the absolute, the end of metaphysics has taken the form of an exacerbated return of the religious.”1 This gives rise to the reduction of religion and anti- religion to fideism. Since both theism and atheism purport to believe in a rationally unsupportable absolute position, they are both symptoms of the return of the religious. -

St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas on the Mind, Body, and Life After Death

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Williams Honors College, Honors Research The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors Projects College Spring 2020 St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas on the Mind, Body, and Life After Death Christopher Choma [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects Part of the Christianity Commons, Epistemology Commons, European History Commons, History of Philosophy Commons, History of Religion Commons, Metaphysics Commons, Philosophy of Mind Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Recommended Citation Choma, Christopher, "St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas on the Mind, Body, and Life After Death" (2020). Williams Honors College, Honors Research Projects. 1048. https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects/1048 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors College at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The University of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Williams Honors College, Honors Research Projects by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 1 St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas on the Mind, Body, and Life After Death By: Christopher Choma Sponsored by: Dr. Joseph Li Vecchi Readers: Dr. Howard Ducharme Dr. Nathan Blackerby 2 Table of Contents Introduction p. 4 Section One: Three General Views of Human Nature p. -

Thomas Aquinas' Argument from Motion & the Kalām Cosmological

University of Central Florida STARS Honors Undergraduate Theses UCF Theses and Dissertations 2020 Rethinking Causality: Thomas Aquinas' Argument From Motion & the Kalām Cosmological Argument Derwin Sánchez Jr. University of Central Florida Part of the Philosophy Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the UCF Theses and Dissertations at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Sánchez, Derwin Jr., "Rethinking Causality: Thomas Aquinas' Argument From Motion & the Kalām Cosmological Argument" (2020). Honors Undergraduate Theses. 858. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses/858 RETHINKING CAUSALITY: THOMAS AQUINAS’ ARGUMENT FROM MOTION & THE KALĀM COSMOLOGICAL ARGUMENT by DERWIN SANCHEZ, JR. A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in Philosophy in the College of Arts and Humanities and in the Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2020 Thesis Chair: Dr. Cyrus Zargar i ABSTRACT Ever since they were formulated in the Middle Ages, St. Thomas Aquinas’ famous Five Ways to demonstrate the existence of God have been frequently debated. During this process there have been several misconceptions of what Aquinas actually meant, especially when discussing his cosmological arguments. While previous researchers have managed to tease out why Aquinas accepts some infinite regresses and rejects others, I attempt to add on to this by demonstrating the centrality of his metaphysics in his argument from motion. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

A Philosophical Investigation of the Nature of God in Igbo Ontology

Open Journal of Philosophy, 2015, 5, 137-151 Published Online March 2015 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojpp http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojpp.2015.52016 A Philosophical Investigation of the Nature of God in Igbo Ontology Celestine Chukwuemeka Mbaegbu Department of Philosophy, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria Email: [email protected] Received 25 February 2015; accepted 3 March 2015; published 4 March 2015 Copyright © 2015 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract In its general task, philosophy as an academic or professional exercise is a conscious, critical, per- sonal reflection on human experience, on man, and how he perceives and interprets his world. This article specifically examines the nature of God in Igbo ontology. It is widely accepted by all philosophers that man in all cultures has the ability to philosophize. This was what Plato and Aris- totle would want us to believe, but it is not the same as saying that man has always philosophized in the academic meaning of the word in the sense of a coherent, systematic inquiry, since power and its use are different things altogether. Using the method of analysis and hermeneutics this ar- ticle sets out to discover, find out the inherent difficulties in the common sense views, ideas and insights of the pre-modern Igbo of Nigeria to redefine, refine and remodel them. The reason is sim- ple: Their concepts and nature of realities especially that of the nature of God were very hazy, in- articulate and confusing. -

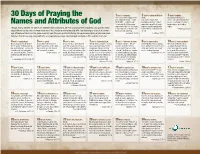

30 Days of Praying the Names and Attributes Of

30 Days of Praying the 1 God is Jehovah. 2 God is Jehovah-M’Kad- 3 God is infinite. The name of the independent, desh. God is beyond measure- self-complete being—“I AM This name means “the ment—we cannot define Him WHO I AM”—only belongs God who sanctifies.” A God by size or amount. He has no Names and Attributes of God to Jehovah God. Our proper separate from all that is evil beginning, no end, and no response to Him is to fall down requires that the people who limits. Though God is infinitely far above our ability to fully understand, He tells us through the Scriptures very specific truths in fear and awe of the One who follow Him be cleansed from —Romans 11:33 about Himself so that we can know what He is like, and be drawn to worship Him. The following is a list of 30 names possesses all authority. all evil. and attributes of God. Use this guide to enrich your time set apart with God by taking one description of Him and medi- —Exodus 3:13-15 —Leviticus 20:7,8 tating on that for one day, along with the accompanying passage. Worship God, focusing on Him and His character. 4 God is omnipotent. 5 God is good. 6 God is love. 7 God is Jehovah-jireh. 8 God is Jehovah-shalom. 9 God is immutable. 10 God is transcendent. This means God is all-power- God is the embodiment of God’s love is so great that He “The God who provides.” Just as “The God of peace.” We are All that God is, He has always We must not think of God ful. -

A Peircean Panentheist Scientific Mysticism1

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 27 | Issue 1 Article 5 1-1-2008 A Peircean Panentheist Scientific ysM ticism Søren Brier Copenhagen Business School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Brier, S. (2008). Brier, S. (2008). A Peircean panentheist scientific ysm ticism. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 27(1), 20–45.. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 27 (1). http://dx.doi.org/10.24972/ijts.2008.27.1.20 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Peircean Panentheist Scientific Mysticism1 Søren Brier2 Copenhagen Business School Copenhagen, Denmark Peirce’s philosophy can be interpreted as an integration of mysticism and science. In Peirce’s philosophy mind is feeling on the inside and on the outside, spontaneity, chance and chaos with a tendency to take habits. Peirce’s philosophy has an emptiness beyond the three worlds of reality (his Categories), which is the source from where the categories spring. He empha- sizes that God cannot be conscious in the way humans are, because there is no content in his “mind.” Since there is a transcendental3 nothingness behind and before the categories, it seems that Peirce had a mystical view on reality with a transcendental Godhead. -

Names of God and Exodus 3:16

Names of God and Exodus 3:16 Jeffrey D. Oldham 2000 July 15 Starting with Exodus 3:16, we will explore the verse's translation and its context to learn about different names for God. (Start by listing as many different names for God as possible. Possibly transliterate a Hebrew word into the Latin alphabet.) 1 Translating the Verse from Hebrew to English Copying from [GRB43], I have listed a word-for-word translation of Exodus 3:16 from Hebrew to English in Table 1. Hebrew writers can add suf®xes to convert one word into a clause so English words appear next to the Hebrew words in the left column. By choosing among the the choices for each Hebrew word, adding punctuation, and rearranging, write the verse in English. Caveat reader: I obtained the Hebrew transliteration words from both [VeW96, Zod84], which differ in the use of accents and in tone. 2 The Verse's Meaning and Context What does the verse mean? What is its context? Who is the speaker, and who is the listener? What is the verse's context? Question to answer at home: What is the relationship with Gen 50:24±25? What verb is used for God's actions? 3 Names for God What names for God does the verse use? What do each of the different names mean? Why so many different names? What other names are used in Exodus 3? Is there a pattern to their use? c 2000 Jeffrey D. Oldham ([email protected]). All rights reserved. This document may not be redistributed in any form without the express permission of the author. -

Lesson 2 – the Eternal Godhead

Mount Zion Ministries Bringing the Power of Resurrection Life to the Nation by Grace alone – through Faith alone – in Christ alone Mount Zion Ministries Discipleship Training Program Lesson 2 – The Eternal Godhead Extracts from the Authorised Version of the Bible (The King James Bible) The rights in which are vested in the Crown Are reproduced with the permission of the Crown’s patentee, Cambridge University Press. Website: mountzionministries.uk Contact: [email protected] Page 1 of 6 Mount Zion Ministries Bringing the Power of Resurrection Life to the Nation by Grace alone – through Faith alone – in Christ alone Lesson 2 – The Eternal Godhead We believe in the Eternal Godhead who has revealed Himself as one God existing in Three Persons, Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, distinguishable but indivisible. Proof texts Matthew 3:16-17 And Jesus, when he was baptized, went up straightway out of the water: and, lo, the heavens were opened unto him, and he saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove, and lighting upon him: And lo a voice from heaven , saying, This is my beloved Son , in whom I am well pleased. Matthew 28:19 Go ye therefore, and teach all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father , and of the Son , and of the Holy Ghost . Mark 1:10-11 And straightway coming up out of the water, he saw the heavens opened, and the Spirit like a dove descending upon him: And there came a voice from heaven , [saying], Thou art my beloved Son , in whom I am well pleased. -

The Holy Spirit: a Personal Member of the Godhead

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Memory, Meaning & Life Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary 6-11-2010 The Holy Spirit: A Personal Member Of The Godhead John Reeve Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/mml Recommended Citation Reeve, John, "The Holy Spirit: A Personal Member Of The Godhead" (2010). Memory, Meaning & Life. 31. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/mml/31 This Blog Post is brought to you for free and open access by the Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Memory, Meaning & Life by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Wayback Machine - http://web.archive.org/web/20180625221757/http://www.memorymeaningfaith.org:80/blog/201… Memory, Meaning & Faith Main About Archives June 11, 2010 The Holy Spirit: A Personal Member Of The Godhead Holy Trinity by Andrei Rublev There is an assertion that floats around the edges of Christianity that the Holy Spirit is not a personal member of the Godhead, but an impersonal power from God. This assertion, which has a small following in Adventism, takes many forms and angles, but at its core it asserts that the Bible does not support a view of the Holy Spirit as having any “personhood.” I will address the issue of the conceptualization of the Holy Spirit directly from the Bible, which, if it gives strong evidence for ascribing personhood and full deity to the Holy Spirit, settles the question for me. -

Biblical Theology of God (Additional Notes on Character of God; Attributes and Who God Is)

Biblical Theology of God (Additional notes on character of God; attributes and who God is) Compilations from some of the pastors at The Grove Kerry Warren: Attributes of God are simply something that God has revealed about Himself. This can’t be confused with what we attribute to God or what we want God to be. I think for most people how they describe God will reveal what they know about Him. For instance, if they say that He is a spiteful God, then their first impression of Him must be that. I think it will say a lot about people when they are asked to list attributes about God. For me God is truth. He doesn’t lie to me or tell me things that I want to hear. He simply speaks truth even if that truth hurts (Deut. 32:4, Ps 33:4). What God says He will do, He will do. Matt Furby: Scripture Key Phrases Attributes Topic Like the appearance of a rainbow in the Ezekiel 1:13- clouds on a rainy day, so was the radiance Indescribable, glorious Awesome 28 around him Job 11:7-9 Can you fathom the mysteries of God? Indescribable, eternal Awesome Awesome, eternal, and the ancient of days took his seat Awesome, Daniel 9:9-14 unique, over all, sovereign given authority, glory, and sovereign power Eternal over all 1 Corinthians No one knows the thoughts of God except Eternal, far above us Eternal 2:11 the Spirit of God in the beginning Creator/maker John 1:1-5 Eternal made all things Eternal No one has ever seen God, but God the One Unique, eternal, far above John 1:18 Eternal and Only has made him known us from everlasting to everlasting you are God Psalm 90:1-4 Eternal Eternal a thousand years in your sight are like a day Revelation Holy Holy Holy Eternal Eternal 4:8-9 Who was, and is, and is to come I am God, and there is no other God is unique and Isaiah 46:9-13 Eternal what I have planned, that will I do unmatched Even to your old age and gray hairs I am he, I am he who will sustain you Sustains His people, does Eternal, Isaiah 46:3-5 To whom will you compare me or count me not grow old Sovereign equal? Be still and know that I am God. -

Ten PROBLEMS with AQUINAS' THIRD

Ten PROBLEMS WITH AQUINAS' THIRD WAY Edward Moad 1. Introduction Of Thomas Aquinas’ five proofs of the existence of God, the Third Way is a cosmological argument of a specific type sometimes referred to as an argument from contingency. The Aristotelian argument for the existence of the First Unmoved Mover was based on the observation that there is change (or motion), coupled with the principle that nothing changes unless its specific potential to change is actualized by an actual change undergone by some other thing. It then arrives at the conclusion that there exists something in a constant state of pure activity, which is not itself moved but sets everything else in motion. The operative sense of contingency this argument turns on, then, is that of motion. That is, things have the potential to change in certain ways (depending on the kind of things they are), but may or may not do so; whether they actually do being contingent on whether they are acted on in the right way by something else. For this reason, Aristotle’s argument delivers a first mover, which brings about the motion in all that exists, but not a being that brings about the very existence of everything else. The argument referred to specifically as the argument from contingency, by contrast, turns on the idea of the contingency of the very existence of anything at all. That is, if something exists which may not have existed, and the fact that it does exist rather than not is contingent on the action of other existing things which are themselves contingent, then the existence of the whole lot of contingent things, taken together, is also contingent.