The 2001 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Community Leadership

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

U.S. and Affiliates, Bermuda and Bahamas

U.S. and Affiliates, Bermuda and Bahamas 65533 District 1 A PAULINE ABADILLA DORIE ARCHETA ELNA AVELINO #### BOBBY BAKER KRISTA BOEHM THOMAS CARLSON #### ARTHUR DILAY ASHLEY HOULIHAN KIM KAVANAGH #### THERESA KUSTA ELENA MAGUAD MARILYN MC LEAN #### DAVID NEUBAUER VICKY SANCHEZ MARIA SCIACKITANO #### RICHARD ZAMLYNSKI #### 65535 District 1 CN CAROLYN GOSHEN BRIAN SCHWARZ PATRICIA TAYLOR #### 65536 District 1 CS KIMBERLY HAMMOND MARK SMITH #### 65537 District 1 D KENNETH BRAMER KARLA BURN TOM HART #### BETSY JOHNSON C. SKOOG #### 65539 District 1 F DAVID GAYTON RACHEL PERKOWITZ LIZZET STONE #### RAYMOND SZULL JOYCE VOLL MICHAEL WITKOWSKI #### 65540 District 1 G GARY EVANS #### 65541 District 1 H BRENDA BIERI JO ANNE NELSON JERRY PEABODY #### GLENN POTTER JERRY PRINE #### Monday, July 02, 2018 Page 1 of 210 Silver Centennial Awards U.S. and Affiliates, Bermuda and Bahamas 65542 District 1 J SHAWN BLOBAUM SEAN BRIODY GREG CLEVENGER #### MITCHELL COHEN TONI HOARLE KEVIN KELLY #### DONALD MC COWAN JAMES WORDEN #### 65545 District 2 T1 MELISSA MARTINEZ MIKE RUNNING SHAWN WILHELM #### RE DONN WOODS #### 65546 District 2 T2 ROBERT CLARK RANDAL PEBSWORTH TOM VERMILLION #### 65547 District 2 T3 JOHN FEIGHERY TARA SANCHEZ #### 65548 District 2 E1 BRYAN ALLEN KENNETH BAKER JAMES BLAYLOCK #### STACY CULLINS SONYA EDWARDS JANNA LEDBETTER #### JOE EDD LEDBETTER KYLE MASTERS LYNDLE REEVES #### JAMES SENKEL CAROLYN STROUD HUGH STROUD #### DIANA THEALL CYNTHIA WATSON #### 65549 District 2 E2 JERRY BULLARD JIMMIE BYROM RALPH CANO #### CHRISANNE CARRINGTON SUE CLAYTON RODNEY CLAYTON #### GARY GARCIA THOMAS HAYFORD TINA JACOBSEN #### JOHN JEFFRIES JOANNA KIMBRELL ELOY LEAL #### JEREMY LONGORIA COURTNEY MCLAUGHLIN LAURIS MEISSNER #### DARCIE MONTGOMERY KINLEY MURRAY CYNTHIA NAPPS #### SIXTO RODRIGUEZ STEVE SEWELL WILLIAM SEYBOLD #### DORA VASQUEZ YOLANDA VELOZ CLIFFORD WILLIAMSON #### LINDA WOODHAM #### Monday, July 02, 2018 Page 2 of 210 Silver Centennial Awards U.S. -

Annual Report 2014–15 © 2015 National Council of Applied Economic Research

National Council of Applied Economic Research Annual Report Annual Report 2014–15 2014–15 National Council of Applied Economic Research Annual Report 2014–15 © 2015 National Council of Applied Economic Research August 2015 Published by Dr Anil K. Sharma Secretary & Head Operations and Senior Fellow National Council of Applied Economic Research Parisila Bhawan, 11 Indraprastha Estate New Delhi 110 002 Telephone: +91-11-2337-9861 to 3 Fax: +91-11-2337-0164 Email: [email protected] www.ncaer.org Compiled by Jagbir Singh Punia Coordinator, Publications Unit ii | NCAER Annual Report 2014-15 NCAER | Quality . Relevance . Impact The National Council of Applied Economic Research, or NCAER as it is more commonly known, is India’s oldest and largest independent, non-profit, economic policy research institute. It is also one of a handful of think tanks globally that combine rigorous analysis and policy outreach with deep data collection capabilities, especially for household surveys. NCAER’s work falls into four thematic NCAER’s roots lie in Prime Minister areas: Nehru’s early vision of a newly- independent India needing independent • Growth, macroeconomics, trade, institutions as sounding boards for international finance, and economic the government and the private sector. policy; Remarkably for its time, NCAER was • The investment climate, industry, started in 1956 as a public-private domestic finance, infrastructure, labour, partnership, both catering to and funded and urban; by government and industry. NCAER’s • Agriculture, natural resource first Governing Body included the entire management, and the environment; and Cabinet of economics ministers and • Poverty, human development, equity, the leading lights of the private sector, gender, and consumer behaviour. -

An Indian Summer: Corruption, Class, and the Lokpal Protests

Article Journal of Consumer Culture 2015, Vol. 15(2) 221–247 ! The Author(s) 2013 An Indian summer: Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav Corruption, class, and DOI: 10.1177/1469540513498614 the Lokpal protests joc.sagepub.com Aalok Khandekar Department of Technology and Society Studies, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Maastricht University, The Netherlands Deepa S Reddy Anthropology and Cross-Cultural Studies, University of Houston-Clear Lake, USA and Human Factors International Abstract In the summer of 2011, in the wake of some of India’s worst corruption scandals, a civil society group calling itself India Against Corruption was mobilizing unprecedented nation- wide support for the passage of a strong Jan Lokpal (Citizen’s Ombudsman) Bill by the Indian Parliament. The movement was, on its face, unusual: its figurehead, the 75-year- old Gandhian, Anna Hazare, was apparently rallying urban, middle-class professionals and youth in great numbers—a group otherwise notorious for its political apathy. The scale of the protests, of the scandals spurring them, and the intensity of media attention generated nothing short of a spectacle: the sense, if not the reality, of a united India Against Corruption. Against this background, we ask: what shared imagination of cor- ruption and political dysfunction, and what political ends are projected in the Lokpal protests? What are the class practices gathered under the ‘‘middle-class’’ rubric, and how do these characterize the unusual politics of summer 2011? Wholly permeated by routine habits of consumption, we argue that the Lokpal protests are fundamentally structured by the impulse to remake social relations in the image of products and ‘‘India’’ itself into a trusted brand. -

Entrance Examination 2020 Ma Communication Media Studies

r ENTRANCE EXAMINATION 2020 Code: W-39 MA COMMUNICATION MEDIA STUDIES MAXIMUM MARKS: 60 DURATION: TWO HOURS IHALL TICKET NUMBER I READ THESE INSTRUCTIONS BEFORE PROCEEDING: • Enter your hall ticket number on the question paper & the OMR sheet without fail • Please read the instructions for each section carefully • Read the instructions on the OMR sheet carefully before proceeding • Answer all questions in the OMR sheet only • Please return the filled in OMR sheet to the invigilator • You may keep the question paper with you • All questions carry equal negative marks. 0.33 marks will be subtracted for every wrong answer • No additional sheets will be provided. Any rough work may be done in the question paper itself TOTAL NUMBER OF PAGES EXCLUDING THIS PAGE: 09 (NINE) r I. GENERAL & MEDIA AWARENESS (lX30=30 MARKS) Enter the correct answer in the OMR sheet 1. Which video conferencing platfotm was found to be leaking personal data to strangers amid the CDVJD-19 crisis? A) Blue Jeans B) Zoom C) Youtube D)GoogleMeet 2. Cox's Bazar in Bangladesh, which has been in the news over the past two years, A) Is a garment district B) Shipbreaking yard C) Has a Rohingya refugee camp D) Beachside tourist spot 3. Satya Nadella is to Microsoft a5_____ is to IBM. A) Sundar Pichai B) Arvind Krishna C) Shantanu Narayan D) Nikesh A 4. Legacy Media is a term used to describe -----=:-:-:c-cc-:-. A) Family run media companies B)Media forms that no longer exist C) Print & broadcast media D) Government-owned media S. The Asian Games 2022 will be held in _____. -

Platform for the Poor (Interview of P

Platform for the Poor (Interview of P. Sainath) By Ashok Mahadevan ill FOR A NEWSPAPER reporter who normally keeps a low profile, Palagummi Sainath was unusually visible in the media just before he talked to Reader's Digest. A fortnight earlier, he had received the prestigious Ramon Magsaysay Award for journalism, literature and the creative communication arts. Then he sparked off a row after criticizing Union Textiles Minister Shanker Sinh Vaghela and Maharashtra Chief Minister Vilasrao Deshmukh for disparaging Maharashtra's cotton farmers—a charge both politicians predictably denied. In fact, we were lucky to find Sainath in his Mumbai home because he travels up to 10 months a year, chronicling the travails of India's poor. He's been doing this for nearly a decade and a half, and his reports reveal a country far different from the "India Shining" of the mainstream media. The economic reforms that began in 1991, Sainath says, while bringing unprecedented prosperity to the middle and upper classes have only deepened the misery of the poor. Sainath, 50, comes from a distinguished family—his grandfather, V. V. Giri, was the fourth President of India. After a master's in history from Jawaharlal Nehru University, Sainath became a journalist in 1980. In 1993, thanks to a fellowship from The Times of India, he investigated living conditions in the country's ten poorest districts. The articles he wrote during this period were collected in a best-selling book called Everybody loves a Good Drought. Sainath, now rural affairs editor of The Hindu, continues to specialize in writing about the poor because, as he puts it, "I felt that if the Indian press was covering the top five percent, I should cover the bottom five percent." Apart from the Magsaysay, Sainath has won many other awards for his work. -

Guest Speakers' Biographies

Guest Speakers’ Biographies OFFICIAL OPENING Minister of State for Overseas Development, Mr Michael Kitt, T.D. Michael P. Kitt, T.D., Minister of State for Overseas Development, was born in Tuam, County Galway in 1950 and lives in Castleblakeney, Ballinsaloe, Galway where he is a public representative for Galway East. Michael comes from a political family and his younger brother and sister are both members of the Dáil as was his father, Michael F. Kitt from 1948 until his death in 1975. Michael is married to Catherine Mannion and has three sons and one daughter. Prior to taking up office as Dáil Deputy in 1981 Michael trained and worked as a national school teacher. In 2002 he was appointed to the Senate by An Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern. Prior to this appointment Michael chaired a sub-committee on over-seas aid and was the Fianna Fáil spokesperson on Emigration and the Developing World. Michael has also been a member of Joint Committees on Foreign Affairs; Agriculture, Food and the Marine; Education and Science and has been a former Minister of State at the Department of An Taoiseach from 1991 -1992. On a local basis, Michael has been a member of Galway County Council, Galway-Mayo Regional Development Board, County Vocational Educational Committee, Galway County Committee of Agriculture, Galway County Library along with Health & National Monuments Committees. Michael has also been a member of the Western Health Board, Council of Europe, Observer Committee to the Western European Union and the Galway County Council Arts Committee as well as the Western Inter-County Railway Committee. -

VIVEKANANDA INTERNATIONAL FOUNDATION 3, San Martin Marg, Chanakyapuri, New Delhi Ph: 011 24121764, 24106698 [email protected]

VIVEKANANDA INTERNATIONAL FOUNDATION 3, San Martin Marg, Chanakyapuri, New Delhi Ph: 011 24121764, 24106698 [email protected] Dear Sir/Madam, As you are aware, the India is passing through its toughest times, when graft and massive illicit wealth are shaking the pillars of its very existence. This, in turn, is pulling back the nation from its aspirations of growth, development and prosperity. At the same time, these issues have created tremendous angst among the people which have manifested in the form of determination to contain the menace through civil actions. Despite all such efforts, we are far behind, even smaller nations in the crusade against illicit money, corruption and bad governance. In this backdrop, we felt that it is our responsibility to initiate a relentless campaign for transparent governance, accountability and firm actions against lack of probity. As a part of this exercise, we are pleased to inform you that an International Seminar on “Transparency and Accountability in Governance – International Experience in the Indian Context” is being organised at Vivekananda International Foundation on April 1 & 2, 2011. This event to be inaugurated by Justice M N Venkatchelliah, former Chief Justice of India, will be attended by a cross section of experts, activists, decision makers and scholars from both inside and outside the country. Towering personalities of Indian polity, judiciary & academia including Dr Subramanian Swamy, K N Govindacharya, Ram Jethmalani, N Gopalaswamy, S Gurumurthy and Justice J S Verma will be delivering their keynote addresses. Eminent experts like Dr.Arun Kumar, Ajit Doval, M D Nalapat, Prof. R Vaidyanathan, Joginder Singh, Nurial Molina, Bhure Lal, Dr.Jayaprakash Narayan, Ram Bahadur Rai, Arvind Kejriwal, TSR Subrahmaniam, Prashant Bhushan, Roland Lomme, David Spencer, B R Lall, Satish Chandra, and many other luminaries will present their papers and take part in the brain storming. -

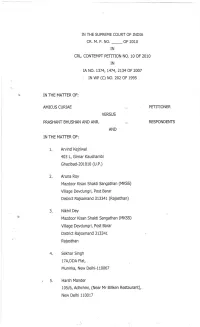

Rn Wp (C) No. 202 of 1995

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDTA cR. M. P. NO. _ OF 2010 IN CRL. CONTEMPT PETMON NO. 10 OF 2O1O IN [A NO. 1374, t474,2L34 OF 2007 rN wP (c) No. 202 oF 1995 IN THE MATTER OF: AMICUS CURIAE PETMONER VERSUS PRASHANT BHUSHAN AND ANR. RESPONDENTS AND IN THE MATTER OF: 1 Arvind Kejriwal 403 L, Girnar Kaushambi Ghazibad-201010 (U.P.) ') Aruna Roy Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS) Village Devdungri, Post Barar District Rajsamand 313341 (Rajasthan) ? NikhilDey Mazdoor Kisan ShaKi Sangathan (MKSS) Village Devdungri, Post Barar District Rajsamand 313341 Rajasthan 4, Sekhar Singh 17A,DDA Flat, Munirka, New Delhi-1 10067 5 Harsh Mander 105/6, Adhchini, (Near Mr Biliken Resiaurant), New Delhi 110017 6 Prof. Jagdeep S. Chhokar A-278, New Friends Colony, New Delhi- 110 025 7 Madhu Bhaduri A 12, IFS Apartments Mayur Vihar Phase -1 New Delhi 8 Rajendra Singh Tarun Ashram, Bheekampura- Kishori Thanagazi, Alwar- 22, Rajasthan 9 Shankar Singh Mazdoor Kisan ShaKi Sangathan (MKSS) Village Devdungri, Post Barar District Rajsamand 313341 (Rajasthan) 10. Amit Bhaduri A 12, IFS APartments Mayur Vihar Phase -1 New Delhi 11. Kalyani Chaudhury Flat No.- 2A, Nayantara Co-oP, DL 28, Salt Lake II, Kolkata -700091 LZ. Madhu Purnima Kishwar C-1/3, Sangam Estate, No. 1 Under Hill Road, Civil Lines, New Delhi - 110 054 13. Manish Sisodia 3501 4 C, Vaftalok Vasundhra, Ghaziabad-201310 (U.P) t4. Abhinandan Sekhri G-601 Som Vihar APartments, R K Pumm, New Delhi 15. Diwan Singh A-9, Chaman Apartment Lane no. 9, Dwarka Sector-23 New Delhi-110077 16. -

Kejriwal to Go up MUMBAI: in Response to Global Prices and Currency IANS Below the Knees, Not Straight at Fluctuations, the Three the Chest and the Throat

www.thepeninsulaqatar.com BUSINESS | 17 SPORT | 24 Japan received over Dideriksen stuns 2,500 LNG cargoes favourites to become from Qatar: Al Kaabi world champion SUNDAY 16 OCTOBER 2016 • 15 MOHARRAM 1438 • Volume 21 • Number 6951 2 Riyals thepeninsulaqatar @peninsulaqatar @peninsula_qatar Private school admission Dr Al Kawari at Peking University period extended till Jan have the right to give priority to Hamad Al Ghali, students from the respective com- munities while admission in other Director of Private schools should be based on results Schools Office at the of the placement tests, in addition to other requirements. Ministry, said that Private schools are not permit- more than 10,000 ted to teach any content that is not in conformity with the culture, values seats currently and religion of the country as well remain vacant in the Qatari laws, said Al Ghali. Any school violating this rule private schools. will be asked to rectify it in the first instance. If it repeats the violation, H E Dr Hamad bin Abdulaziz Al Kawari, Cultural Adviser at the Emiri Diwan and Qatar’s candidate for the Ministry will apply the provisions the post of Director-General of Unesco, with officials at the Peking University (PKU) in Beijing. Dr Al By Mohammed Osman Peninsula in an exclusive interview. of Decision No. 23 of 2015, which Kawari has stressed the depth of relations between the Arab and Chinese cultures. → See also page 3 The Peninsula He said that 18 newly-opened stipulated stopping privileges pro- schools alone have 7,667 vacant seats vided by the ministry, fines up to in addition to 2,800 seats which QR200,000, cancellation of licence were already available. -

![7RZ]VU E` WVV] 5V]YZ Af]Dv+ DYRY](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5188/7rz-vu-e-wvv-5v-yz-af-dv-dyry-1005188.webp)

7RZ]VU E` WVV] 5V]YZ Af]Dv+ DYRY

>/ . 7 7 7 SIDISrtVUU@IB!&!!"&#S@B9IV69P99I !%! %! ' #%&'#( )*+, 2(%3%234 12$/ ), (2$)5 83680)2,) 434+238?3) 43/@A$)! ,+3))!221 /)01208 94! 614+06186+)!+3 436)2-2E /)+13)43)/2"/+B 0+B)34B)+3+!+3/ 3+ 123+283 1+/2E+31 /)13+/8 1B/)3+6+/2-+B!+/+ 0 !" "$##$ $C D+ ) + ), -.-./ )+ - )!/)012 ! n a candid admission, Union IHome Minister Amit Shah on Thursday said his assess- ment of Delhi Assembly elec- Q tions went wrong and main- tained that the statements like tually non-existent in Bihar. We “goli maro” and “Indo-Pak are almost extinct in UP but we R match” (in reference to ! ! are strong in Rajasthan, Shaheen Bagh) by party’s Madhya Pradesh and motormouths hurt the BJP’s & Chhattisgarh. In Haryana, we prospects in the polls. have come back,” he said. )!/)012 While maintaining that At the same time Jairam such remarks should not have )!/)012 claimed the Delhi election he Government on been made, he said the Delhi result was rejection of Home TThursday renamed Pravasi two institutions have been poll results were not a mandate he Congress drubbing in Minister Amit Shah, who was Bharatiya Kendra and Foreign renamed in solemn tribute to on the CAA and the National Tthe Delhi Assembly elec- the chief campaigner of the BJP. Service Institute after late the “invaluable contribution” of Register of Citizens (NRC). tions has led to intense resent- before the people. “It is a resounding slap on his Sushma Swaraj. The decision to Sushma to Indian diplomacy, While Union Minister ment in the rank and file of the “This (Delhi Assembly face and it is a rejection of the name the two institutes after the cause of the Indian diaspora Anurag Thakur and West Delhi party with senior leaders like result) is very disappointing. -

Download Brochure

Celebrating UNESCO Chair for 17 Human Rights, Democracy, Peace & Tolerance Years of Academic Excellence World Peace Centre (Alandi) Pune, India India's First School to Create Future Polical Leaders ELECTORAL Politics to FUNCTIONAL Politics We Make Common Man, Panchayat to Parliament 'a Leader' ! Political Leadership begins here... -Rahul V. Karad Your Pathway to a Great Career in Politics ! Two-Year MASTER'S PROGRAM IN POLITICAL LEADERSHIP AND GOVERNMENT MPG Batch-17 (2021-23) UGC Approved Under The Aegis of mitsog.org I mitwpu.edu.in Seed Thought MIT School of Government (MIT-SOG) is dedicated to impart leadership training to the youth of India, desirous of making a CONTENTS career in politics and government. The School has the clear § Message by President, MIT World Peace University . 2 objective of creating a pool of ethical, spirited, committed and § Message by Principal Advisor and Chairman, Academic Advisory Board . 3 trained political leadership for the country by taking the § A Humble Tribute to 1st Chairman & Mentor, MIT-SOG . 4 aspirants through a program designed methodically. This § Message by Initiator . 5 exposes them to various governmental, political, social and § Messages by Vice-Chancellor and Advisor, MIT-WPU . 6 democratic processes, and infuses in them a sense of national § Messages by Academic Advisor and Associate Director, MIT-SOG . 7 pride, democratic values and leadership qualities. § Members of Academic Advisory Board MIT-SOG . 8 § Political Opportunities for Youth (Political Leadership diagram). 9 Rahul V. Karad § About MIT World Peace University . 10 Initiator, MIT-SOG § About MIT School of Government. 11 § Ladder of Leadership in Democracy . 13 § Why MIT School of Government.