Platform for the Poor (Interview of P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entrance Examination 2020 Ma Communication Media Studies

r ENTRANCE EXAMINATION 2020 Code: W-39 MA COMMUNICATION MEDIA STUDIES MAXIMUM MARKS: 60 DURATION: TWO HOURS IHALL TICKET NUMBER I READ THESE INSTRUCTIONS BEFORE PROCEEDING: • Enter your hall ticket number on the question paper & the OMR sheet without fail • Please read the instructions for each section carefully • Read the instructions on the OMR sheet carefully before proceeding • Answer all questions in the OMR sheet only • Please return the filled in OMR sheet to the invigilator • You may keep the question paper with you • All questions carry equal negative marks. 0.33 marks will be subtracted for every wrong answer • No additional sheets will be provided. Any rough work may be done in the question paper itself TOTAL NUMBER OF PAGES EXCLUDING THIS PAGE: 09 (NINE) r I. GENERAL & MEDIA AWARENESS (lX30=30 MARKS) Enter the correct answer in the OMR sheet 1. Which video conferencing platfotm was found to be leaking personal data to strangers amid the CDVJD-19 crisis? A) Blue Jeans B) Zoom C) Youtube D)GoogleMeet 2. Cox's Bazar in Bangladesh, which has been in the news over the past two years, A) Is a garment district B) Shipbreaking yard C) Has a Rohingya refugee camp D) Beachside tourist spot 3. Satya Nadella is to Microsoft a5_____ is to IBM. A) Sundar Pichai B) Arvind Krishna C) Shantanu Narayan D) Nikesh A 4. Legacy Media is a term used to describe -----=:-:-:c-cc-:-. A) Family run media companies B)Media forms that no longer exist C) Print & broadcast media D) Government-owned media S. The Asian Games 2022 will be held in _____. -

Guest Speakers' Biographies

Guest Speakers’ Biographies OFFICIAL OPENING Minister of State for Overseas Development, Mr Michael Kitt, T.D. Michael P. Kitt, T.D., Minister of State for Overseas Development, was born in Tuam, County Galway in 1950 and lives in Castleblakeney, Ballinsaloe, Galway where he is a public representative for Galway East. Michael comes from a political family and his younger brother and sister are both members of the Dáil as was his father, Michael F. Kitt from 1948 until his death in 1975. Michael is married to Catherine Mannion and has three sons and one daughter. Prior to taking up office as Dáil Deputy in 1981 Michael trained and worked as a national school teacher. In 2002 he was appointed to the Senate by An Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern. Prior to this appointment Michael chaired a sub-committee on over-seas aid and was the Fianna Fáil spokesperson on Emigration and the Developing World. Michael has also been a member of Joint Committees on Foreign Affairs; Agriculture, Food and the Marine; Education and Science and has been a former Minister of State at the Department of An Taoiseach from 1991 -1992. On a local basis, Michael has been a member of Galway County Council, Galway-Mayo Regional Development Board, County Vocational Educational Committee, Galway County Committee of Agriculture, Galway County Library along with Health & National Monuments Committees. Michael has also been a member of the Western Health Board, Council of Europe, Observer Committee to the Western European Union and the Galway County Council Arts Committee as well as the Western Inter-County Railway Committee. -

37Th ANNUAL REPORT

UNIVERSITY OF HYDERABAD 37th ANNUAL REPORT Report on the working of the University (1 April 2011 to 31 March 2012) Prof. C. R. Rao Road Central University P.O. Gachibowli, Hyderabad – 500 046 www.uohyd.ac.in beforePages.indd 1 2/20/2013 6:59:11 PM Our Motto forms part of a verse appearing in Vishnu-Purana (1.19.41) The whole verse reads as follows : The verse also occurs in the anthology of subhasitas entitled "Sarangadharapaddhati" (No.4396). In this latter work, the source of the verse is given as Vasisthat. The verse obviously possesses an ethical-spiritual import and may be translated as follows: “That is (right) action which does not conduce to bondage (Karmabandha in the Bhagavadgita sense); that is (true) knowledge which conduces to final liberation or spiritual emancipation; (any) other knowledge implies mere skill in craft beforePages.indd 2 2/20/2013 6:59:12 PM Visitor The President of India Chief Rector The Governor of Andhra Pradesh Chancellor R Chidambaram (upto 11.01.2012) C H Hanumantha Rao (12.01.2012) Vice-Chancellor Ramakrishna Ramaswamy Pro Vice-Chancellor E. Haribabu Deans of Schools Mathematics & C.I.S. T Amaranath, Ph.D. (I.I.T., Madras) Physics C Bansal, Ph.D. (TIFR., Bombay) Chemistry M V Rajasekharan, Ph.D.(IIT, Madras) Life Sciences M Ramanadham, Ph.D. (OU, Hyderabad) Humanities Mohan G Ramanan, Ph.D. (BITS, Pilani) Social Sciences G Nancharaiah, Ph.D. (AU, Visakhapatnam) Sarojini Naidu School of Vinod Pavarala, Ph.D. (University of Pittsburgh) Arts and Communication (upto 18.03.2012) B Anandhakrishnan, Ph.D. -

Solved Paper of UPSC Civil Services Preliminary Exam 2001 Exam

Solved Paper of UPSC Civil Services Preliminary Exam 2001 Exam Q1 In what way does the Indian Parliament exercise control over the administration? (a) Through Consultative Committees of various ministries (b) Through Parliamentary Committees (c) By making the administrators send periodic reports (d) By compelling the executive to issue writs Correct Answer is (b) Through Parliamentary Committees Functions of Parliamentary Committees Parliamentary committees can range over all the functions that the legislature itself performs, with the exception of determining the formation of the Government. They perform functions which Houses of Parliament are not as well-fitted to perform, such as finding out facts of a case or issue, examining witnesses, sifting evidence and drawing up reasoned conclusions. Accountability Committees provide an increased ability for the Parliament to scrutinise government policy and expenditure. Committees are frequently appointed to parallel the ministerial or departmental structure adopted by the Executive. Each committee has a responsibility to provide oversight of government agencies within specific portfolios. Legislation Committees can be an important part of the legislative process. Examination by a committee can allow public input into the legislative process. Representation / Education of Members Committees enable the Parliament to be taken to the people, and enable evidence to be gathered from expert groups or individuals. They enable direct contact between the public and representative groups of Members of Parliament and a flow of information to Members. They facilitate an increased level of collegiality between members from different political parties who may not otherwise have the opportunity to work with one another. The accountability functions of parliamentary committees include their ability: to conduct inquiries; to compel the attendance of persons and presentation of documents; and to make reports and recommendations to Parliament. -

The Mario Einaudi Center for International Studies

the mario einaudi center for international studies CORNELL UNIVERSITY 1996-97 ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS About This Report.............................................................................. 1 Mission Statement ............................................................................. 2 The Mario Einaudi Center For International Studies The Mario Einaudi Center for International Studies ....................................................................3 Area Studies Programs East Asia....................................................................................................................................... 7 Institute for African Development.............................................................................................. 13 Institute for European Studies .................................................................................................... 16 Latin American Studies ............................................................................................................. 24 South Asia .................................................................................................................................. 31 Southeast Asia ............................................................................................................................ 38 Development Studies Programs Comparative Economic Development .......................................................................................42 Cornell Ford and Nutrition Policy .............................................................................................44 -

The 2001 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Community Leadership

The 2001 Ramon Magsaysay Award and streams. Moreover, villagers could make for Community Leadership johads themselves using local skills and traditional technology. Rajendra Singh As TBS went to work, SINGH recruited a small staff of social workers and hundreds of volunteers. Expanding village by village--to 750 villages today--he and his team helped people identify their water-harvesting needs and assisted them with projects, but only when the entire village committed itself and pledged to meet half the costs. Aside from johads, TBS helped villagers repair wells and other old structures and mobilized them to plant trees on the hillsides to prevent erosion and restore the watershed. SINGH coordinated all these activities to mesh with the villagers' traditional cycle of rituals. Meanwhile, with others, TBS waged a long and ultimately successful campaign to Even in the best of times, it is arid in the Alwar persuade India's Supreme Court to close district of Rajasthan, India. Yet not so long ago, hundreds of mines and quarries that were streams and rivers in Alwar's forest-covered despoiling Sariska National Park. foothills watered its villages and farms dependably and created there a generous if Guided by Gandhi's teachings of local autonomy fragile human habitat. People lived prudently and self-reliance, SINGH has introduced within this habitat, capturing precious monsoon community-led institutions to each village. The rainwater in small earthen reservoirs called Gram Sabha manages water conservation johads and revering the forest, from which they structures and sets the rules for livestock grazing took sparingly. and forest use. The Mahila Mandal organizes the local women's savings and credit society. -

Fukuoka Prize 2021 Grand Prize PALAGUMMI Sainath

Fukuoka Prize 2021 Grand Prize PALAGUMMI Sainath India Journalist People's Archive of Rural India Founder Editor Born May 13, 1957(Age 64) Biography 1957 Born in Chennai (formerly known as Madras), India 1977 B.A. History, Loyola College, Madras 1979 M.A. History, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi 1980‐82 Sub Editor, United News of India 1982‐93 Deputy Chief Editor , and Foreign Editor, Blitz group of Publications 1982‐86 Foreign Editor at The Daily, Mumbai (till 1986, a part of the Blitz group) 1993‐2004 Full‐time rural reporter, freelance 2000‐ Adjunct Faculty, Asian College of Journalism, Chennai 2004‐14 Rural Affairs Editor, The Hindu 2011 Doctor of Letters (D.Litt.) honoris causa, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada 2012 the McGraw Professor of Writing, Princeton University, U.S.A. 2014 Founded People’s Archive of Rural India 2014‐ Founder Editor, People’s Archive of Rural India 2015 Visiting Professor South Asian Studies Program Princeton University 2017 Doctorate (honoris causa) a D.Litt., the University of St. Francis Xavier, Nova Scotia, Canada Mr. Palagummi Sainath has also taught at the University of California, Berkeley (U.S.A.), the University of Iowa, Curtin University (Australia), The University of Western Ontario (Canada). He still teaches regular courses at the Sophia Polytechnic and the Asian College of Journalism in India. Major Awards 1993 The Sri Raja‐Lakshmi Award for Journalism 1994 The Statesman Prize for Rural Reporting 1995 European Commissionʹs Lorenzo Natali Prize for journalism 1995 People’s Union -

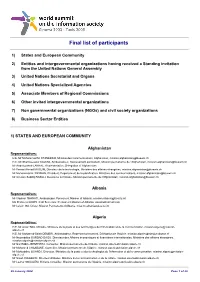

Final List of Participants

Final list of participants 1) States and European Community 2) Entities and intergovernmental organizations having received a Standing invitation from the United Nations General Assembly 3) United Nations Secretariat and Organs 4) United Nations Specialized Agencies 5) Associate Members of Regional Commissions 6) Other invited intergovernmental organizations 7) Non governmental organizations (NGOs) and civil society organizations 8) Business Sector Entities 1) STATES AND EUROPEAN COMMUNITY Afghanistan Representatives: H.E. Mr Mohammad M. STANEKZAI, Ministre des Communications, Afghanistan, [email protected] H.E. Mr Shamsuzzakir KAZEMI, Ambassadeur, Representant permanent, Mission permanente de l'Afghanistan, [email protected] Mr Abdelouaheb LAKHAL, Representative, Delegation of Afghanistan Mr Fawad Ahmad MUSLIM, Directeur de la technologie, Ministère des affaires étrangères, [email protected] Mr Mohammad H. PAYMAN, Président, Département de la planification, Ministère des communications, [email protected] Mr Ghulam Seddiq RASULI, Deuxième secrétaire, Mission permanente de l'Afghanistan, [email protected] Albania Representatives: Mr Vladimir THANATI, Ambassador, Permanent Mission of Albania, [email protected] Ms Pranvera GOXHI, First Secretary, Permanent Mission of Albania, [email protected] Mr Lulzim ISA, Driver, Mission Permanente d'Albanie, [email protected] Algeria Representatives: H.E. Mr Amar TOU, Ministre, Ministère de la poste et des technologies -

Buying Cialis

Pravara Medical Trust’s Arts, Commerce and Science College Shevgaon, Dist. Ahmednagar ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Proceedings of Seminar on PERSPECTIVES ON ENVIRONMENT DEGRADATION AND AGRARIAN CRISIS IN INDIA Edited By Dr. Onkar Rasal Assistant Professor and Head, Department of Economics PMT’S Arts, Commerce and Science College, Shevgaon, Dist- Ahmednagar (MS) India. [email protected]/9422855890 Dr. Yuvraj Patil Narawade Assistant Professor, PIRENS, IBME, Loni 2018 Ideal International E – Publication Pvt. Ltd. www.isca.co.in 427, Palhar Nagar, RAPTC, VIP-Road, Indore-452005 (MP) INDIA Phone: +91-731-2616100, Mobile: +91-80570-83382 E-mail: [email protected] , Website: www.isca.co.in Title: Proceedings of Seminar on Perspectives on Environment Degradation and Agrarian Crisis in India. Editor(s): Dr. Onkar Rasal, Dr. Yuvraj Patil Narawade Edition: First Volume: I © Copyright Reserved 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, reordering or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-93-86675-30-9 Proceedings of Seminar on Perspectives on Environment Degradation and Agrarian Crisis in India. iii PREFACE Economic development during post reforms period have drastically change an environment of the country. According to the models of economic growth and development; development at the cost of environment will never helps to achieve the goal of inclusive and sustainable development. Mere negligence of the agrarian and environmental issues in the policy domain will further worsen the situation. Day by day declining quality of the environment will leads to the multiplier effects on the factor productivity. -

MICA-JULY-ENG-2021.Pdf

TOP NOTCH CAPTIVATORS OF THE MONTH Deepika Kumari bags 3 Gold World No.1 Novak Djokovic medals at Archery World Cup clinches his second French 1 stage III in Paris. open Men's Singles title. 2 Environment conservation Wrestler Vinesh Phogat wins concept, Familial Forestry has gold in women's 53 kg won this year's prestigious freestyle at Poland Ranking 3 United Nations' Land for 4 Series. Life Award. Engineers India Limited CMD Journalist Palagummi Sainath RK Sabharwal has been has been awarded the honoured with the highest 5 Fukuoka Grand Prize for 2021. civilian award of Mongolia 6 'The Order of Polar Star'. Indian actress Tillotama “At Night All Blood is Black” Shome won the Best Actor by French writer David Diop award at the 2021 UK Asian won the International Booker 8 7 Film Festival (UKAFF). Prize for fiction. International Yoga Day is Indian sprint legend Milkha celebrated across the world Singh died after a month-long 9 on 21st June. battle with Covid-19. 10 Mahendra Publication Pvt. Ltd. CONTENTS VOL-17 ISSUE -07 Editor N.K. Jain Advisors Prime Minister’s participation Delta plus variant Neeraj Chabra in 47th G7 Summit K.C.Gupta Registered Office Mahendra Publication Pvt. Ltd. 103, Pragatideep Building, Plot No. 08, Laxminagar, District Centre, New Delhi - 110092 Israeli–Palestinian The Taliban Returns TIN-09350038898 conflict w.e.f. 12-06-2014 Branch Office Mahendra Publication Pvt. Ltd. E-42,43,44, Sector-7, Noida (U.P.) For queries regarding promotion, distribution & Interview 5 advertisement, contact:- Current Affairs - One Liner 6-9 [email protected] Spotlight 10 Ph.: 09208037962 The People 11-21 Owned, printed & published by News Bites 22-60 N.K. -

Seth G.S. Medical College & King Edward

annual report 2020 SETH G.S. MEDICAL COLLEGE & KING EDWARD MEMORIAL HOSPITAL Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai The year that was….. Seth G.S. Medical College & King Edward Memorial Hospital Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Concept (Front & Back cover) Dr. Hemant Deshmukh Dean (Seth G.S. Medical College & KEM Hospital) Dr.Milind Nadkar Academic Dean Editor in Chief Dr. Nithya Gogtay Editors Dr. Gita Nataraj Dr. Raakhi Tripathi Dr. Shruti Bhide Associate Editors Dr. Vijaya Gunjal Dr. Palvi Kudyar Dr. Sukant Pandit Dr. Dhruve Soni Funding Support Diamond Jubilee Society Trust Department Development Fund Research Society Printer Urvi Compugraphics A2/248, Shah & Nahar Industrial Estate, S.J. Marg, Lower Parel (West) Mumbai 400 013. Tel.: 91 - 22 - 2494 5863 • e-mail: [email protected] © Seth GS Medical College & KEM Hospital, Mumbai Acknowledgements WE ARE GRATEFUL TO Smt. Kishoritai Pednekar Hon. Mayor of Mumbai Shri. Suhas Wadkar Deputy Mayor of Mumbai • Smt. Vishakha Raut • Shri. I. S. Chahal Leader of the House Municipal Commissioner • Shri. Ravi Raja • Shri. Suresh Kakani Leader of the Opposition AMC- Western Suburbs • Shri. Yashwant Jadhav • Shri. Velrasu Chairman-Standing Committee AMC- Projects • Shri. Pravina Morajkar • Shri. Sanjeev Jaiswal Chairman, Public Health Committee AMC-City • Shri. Ramdas Kamble • Smt. Ashwini Bhide Chairperson, F/South Ward Committee AMC-Eastern Suburbs • Shri. Devidas Kshirsagar (PH) Dy. Municipal Commissioner From the Dean’s desk..... The twin institutes of the Seth GS Medical College & KEM Hospital were established in 1926 with a nationalistic spirit to cater to the “health care needs of the northern parts of the island” to be manned entirely by Indians. -

Conceptualizing the State-Nation Via Education Reform: from Multicultural to Intercultural Citizenship

Conceptualizing the State-Nation via Education Reform: From Multicultural to Intercultural Citizenship by Neville Gustad Panthaki A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Social Justice Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Neville Gustad Panthaki 2016 Conceptualizing the State-Nation via Education Reform: From Multicultural to Intercultural Citizenship Neville Gustad Panthaki Doctor of Philosophy Department of Social Justice Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto 2016 Abstract Transnational movements of sociopolitical culture defy the integrity of the nation-state. Its organizational principle of singularity, and struggles to accommodate increasing diversity within homogeneity, are challenged by the increasing prominence of alternate and multiple ways of being and knowing. Nation-state education systems organized to deliver citizenship values, fail to rectify the fracture between their quest for multicultural participation and their promotion of conformity within a single ‘national’ identity. Systems of education are products of their respective sociopolitical systems. Hence, notions of citizenship (inclusion) and democracy (participation) must be reformed to facilitate genuine education reform. The nation-state is a sociopolitical project that confines pedagogical reform within the framework of a paradigm. Education reform can only be achieved by substituting the concept of multi-cultural, with inter-cultural citizenship, thereby transforming the unidimensional nation-state into a pluralist state-nation. The state-nation is an ideal-type conceptual framework which is predicated upon a constant (re-)negotiation of categories and their corresponding ii belonging-identities, so that all boundaries remain liminal and permeable rather than immutable and exclusionary.