Waltham Forest College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

College Employer Satisfaction League Table

COLLEGE EMPLOYER SATISFACTION LEAGUE TABLE The figures on this table are taken from the FE Choices employer satisfaction survey taken between 2016 and 2017, published on October 13. The government says “the scores calculated for each college or training organisation enable comparisons about their performance to be made against other colleges and training organisations of the same organisation type”. Link to source data: http://bit.ly/2grX8hA * There was not enough data to award a score Employer Employer Satisfaction Employer Satisfaction COLLEGE Satisfaction COLLEGE COLLEGE responses % responses % responses % CITY COLLEGE PLYMOUTH 196 99.5SUSSEX DOWNS COLLEGE 79 88.5 SANDWELL COLLEGE 15678.5 BOLTON COLLEGE 165 99.4NEWHAM COLLEGE 16088.4BRIDGWATER COLLEGE 20678.4 EAST SURREY COLLEGE 123 99.2SALFORD CITY COLLEGE6888.2WAKEFIELD COLLEGE 78 78.4 GLOUCESTERSHIRE COLLEGE 205 99.0CITY COLLEGE BRIGHTON AND HOVE 15088.0CENTRAL BEDFORDSHIRE COLLEGE6178.3 NORTHBROOK COLLEGE SUSSEX 176 98.9NORTHAMPTON COLLEGE 17287.8HEREFORDSHIRE AND LUDLOW COLLEGE112 77.8 ABINGDON AND WITNEY COLLEGE 147 98.6RICHMOND UPON THAMES COLLEGE5087.8LINCOLN COLLEGE211 77.7 EXETER COLLEGE 201 98.5CHESTERFIELD COLLEGE 20687.7WEST NOTTINGHAMSHIRE COLLEGE242 77.4 SOUTH GLOUCESTERSHIRE AND STROUD COLLEGE 215 98.1ACCRINGTON AND ROSSENDALE COLLEGE 14987.6BOSTON COLLEGE 61 77.0 TYNE METROPOLITAN COLLEGE 144 97.9NEW COLLEGE DURHAM 22387.5BURY COLLEGE121 76.9 LAKES COLLEGE WEST CUMBRIA 172 97.7SUNDERLAND COLLEGE 11487.5STRATFORD-UPON-AVON COLLEGE5376.9 SWINDON COLLEGE 172 97.7SOUTH -

London ESF Youth Programme Providers

London ESF Youth Programme Providers Information is based on the latest data provided to the GLA. If you think the information here is incorrect please inform us by emailing: [email protected] Strand Contract Lead Lead Provider Contact Delivery Partner Name Contact Details (Name, email and phone no) Delivery Location(s) [email protected] Groundwork Big Creative Playback Studios Newham Council Newham College Barking & Dagenham, Enfield, Greenwich, Hackney, Haringey, Havering Think Forward Urban Futures REED in Partnership The Challenge NXG Preventative NEET North & North East Prevista Ameel Beshoori, [email protected] Cultural Capital Central Prevista Ameel Beshoori, [email protected] Groundowrk [email protected] Lewisham, Southwark, Lambeth, Wandsworth, Big Creative City of London, Westminster, Kensington & Chelsea, Camden and Islington The Write Time Playback Studios Think Forward PSEV NXG Inspirational Youth South Prevista Ameel Beshoori, [email protected] Groundwork Bexley, Bromley, Croydon, Sutton, Merton, The Write Time Kingston and Richmond [email protected] Playback Studios Prospects Richmond Council All Dimensions Barnet Brent Ealing Hammersmith & Fulham NXG Harrow Hillingdon Hounslow Cultural Capital West Prevista Ameel Beshoori, [email protected] Groundwork Playback Studios [email protected] Urban Futures PSEV REED in Partnership NEET Outreach North & North East Reed In Partnership Freddie Sumption, [email protected] City Gateway Katherine Brett, [email protected] Delivery: -

Open Letter to Address Systemic Racism in Further Education

BLACK FURTHER EDUCATION LEADERSHIP GROUP 5th August 2020 Open letter to address systemic racism in further education Open letter to: Rt. Hon. Boris Johnson, Prime Minister, Rt. Hon. Gavin Williamson MP, Secretary of State for Education, funders of further education colleges; regulatory bodies & further education membership bodies. We, the undersigned, are a group of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) senior leaders, and allies, who work or have an interest in the UK further education (FE) sector. The recent #BlackLivesMatter (#BLM) global protest following the brutal murder of George Floyd compels us all to revisit how we address the pervasive racism that continues to taint and damage our society. The openness, solidarity and resolve stirred by #BLM is unprecedented and starkly exposes the lack of progress made in race equality since ‘The Stephen Lawrence Enquiry’. Against a background of raised concerns about neglect in healthcare, impunity of policing, cruelty of immigration systems – and in education, the erasure of history, it is only right for us to assess how we are performing in FE. Only by doing so, can we collectively address the barriers that our students, staff and communities face. The personal, economic and social costs of racial inequality are just too great to ignore. At a time of elevated advocacy for FE, failure to recognise the insidious nature of racism undermines the sector’s ability to fully engage with all its constituent communities. The supporting data and our lived experiences present an uncomfortable truth, that too many BAME students and staff have for far too long encountered a hostile environment and a system that places a ‘knee on our neck’. -

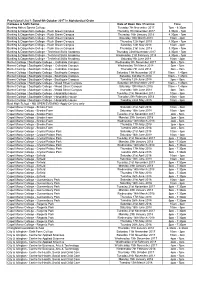

Provisional List 1: Dated 9Th October 2017 in Alphabetical Order

Provisional List 1: Dated 9th October 2017 in Alphabetical Order Colleges & Sixth Forms Date of Open Day / Evening Time Barking Abbey Sports College Tuesday 7th November 2017 7pm - 8:30pm Barking & Dagenham College - Rush Green Campus Thursday 7th December 2017 3.30pm - 7pm Barking & Dagenham College - Rush Green Campus Thursday 18th January 2018 4.30pm - 7pm Barking & Dagenham College - Rush Green Campus Saturday 10th March 2018 10am - 2pm Barking & Dagenham College - Rush Green Campus Thursday 12th April 2018 4.30pm - 7pm Barking & Dagenham College - Rush Green Campus Saturday 12th May 2018 10am - 2pm Barking & Dagenham College - Rush Green Campus Thursday 21st June 2018 3.30pm - 7pm Barking & Dagenham College - Technical Skills Academy Thursday 23rd November 2017 4.30pm - 7pm Barking & Dagenham College - Technical Skills Academy Wednesday 21st February 2018 4.30pm - 7pm Barking & Dagenham College - Technical Skills Academy Saturday 9th June 2018 10am - 2pm Barnet College / Southgate College - Colindale Campus Wednesday 8th November 2017 5pm - 7pm Barnet College / Southgate College - Colindale Campus Wednesday 7th March 2018 5pm - 7pm Barnet College / Southgate College - Colindale Campus Thursday 7th June 2018 3pm – 7pm Barnet College / Southgate College - Southgate Campus Saturday 11th November 2017 10am – 1:45pm Barnet College / Southgate College - Southgate Campus Saturday 3rd March 2018 10am – 1:45pm Barnet College / Southgate College - Southgate Campus Tuesday 12th June 2018 3pm – 7pm Barnet College / Southgate College - Wood Street -

Arts Award & Beyond

Arts Award & Beyond... Developing Creative Opportunities for Young People across Waltham Forest Report of current provision with Project Action Plan By Laura Elliott, Project Consultant and Coordinator November 2013 – March 2014 CONTENTS Acknowledgements i Explanation of key organisations and terms ii Executive summary iv Project Action Plan vii 1. Introduction 1 1.1 About the report 1 1.2 Research methodology 1 1.3 Report aims and objectives 2 2. Key findings and recommendations 3 2.1 Identify existing arts provision for young people aged 14-25 3 2.2 Identify main structures of communication for arts providers 7 2.3 Provide an overview of the organisation of work experience, apprenticeships and volunteering 9 2.4 Identify the main benefits of Arts Award to education providers 10 2.5 Identify the main incentives and barriers to participation 12 2.6 Identify and encourage new partner organisations able to engage young people not currently participating in the arts 15 2.7 Summary of the full recommendations with action points 16 3. Project Action Plan up to March 2014 17 3.1 Project milestones 18 4 Conclusion 19 Sources 20 Appendices 21 Appendix i: Table of Arts Award and Artsmark activity in schools 21 Appendix ii: List of Waltham Forest education, youth and arts organisations working with young people aged 16-25 22 Appendix iii: Waltham Forest schools networks 26 a) Table of Waltham Forest Area Partnerships 25 b) List of Waltham Forest Schools Networks 26 c) Case Studies of information networks used by two WFAEN member schools 28 Appendix iv: Survey and consultation results 29 Appendix v: Sample of questionnaire 30 Appendix vi: Consultation exercise and notes 33 a) Barriers and benefits 33 b) Next steps: Communication 35 c) Next steps: Work experience 36 Cover illustration: Students from Chingford Foundation School displaying relief prints completed during a workshop at the William Morris Gallery attended as part of their Bronze Arts Award. -

Post 16 High Needs Funding Pdf 738 Kb

x 1.0 SEND Reforms: The SEND reforms 2014 have changed the legislation over duties to provide support to children. The key features of the reform agenda are: A requirement for the Authority and local Schools to publish their ‘Local Offer’ for Families and Young People with SEN and Disabilities on their websites Education, Health and Social Care Plans (EHC plans) to replace statements, but the threshold to remain as the child’s significant learning need. These to be issued within 20 weeks The use of a personal budget for services within the Education, Health and Care Plan Extension of the EHC plan to 25 years for Young People in Education The extension of the duty to include children and young people in Youth Offending Services Joint Commissioning between Health, Education and Social Care Collaboration and Co-production with families and children The reforms have increased the need for resources for an extended age range of children and young people to be assessed for, and provided with support in education, potentially up to the age of 25 years. This report will focus on the population, funding and educational outcomes for young people aged 16- 25 years 1.1 Population of children with SEN and Disabilities: 1.1.1.In April 2016 Haringey had 1600 children and young people with Statements of SEN and Young People with Learning Difficulty Assessments, this is an increase of 91 children from 2014-2015 where there were 1414 with statements and 100 with LDA’s. In April 2017 this had increased to 1790, an increase of 9% over the previous year. -

Progression of College Students in London to Higher Education 2011 - 2014

PROGRESSION OF COLLEGE STUDENTS IN LONDON TO HIGHER EDUCATION 2011 - 2014 Sharon Smith, Hugh Joslin and Jill Jameson Prepared for Linking London by the HIVE-PED Research Team, Centre for Leadership and Enterprise in the Faculty of Education and Health at the University of Greenwich Authors: Sharon Smith, Hugh Joslin and Professor Jill Jameson Centre for Leadership and Enterprise, Faculty of Education and Health University of Greenwich The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Linking London, its member organisations or its sponsors. Linking London Birkbeck, University of London BMA House Tavistock Square London WC1H 9JP http://www.linkinglondon.ac.uk January 2017 Linking London Partners – Birkbeck, University of London; Brunel University, London; GSM London; Goldsmiths, University of London; King’s College London; Kingston University, London; London South Bank University; Middlesex University; Ravensbourne; Royal Central School for Speech and Drama; School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London; University College London; University of East London; University of Greenwich; University of Westminster; Barnet and Southgate College; Barking and Dagenham College; City and Islington College; City of Westminster College; The College of Enfield, Haringey and North East London; Harrow College; Haringey Sixth Form College; Havering College of Further and Higher Education; Hillcroft College; Kensington and Chelsea College; Lambeth College; Lewisham Southwark College; London South East Colleges; Morley College; Newham College of Further Education; Newham Sixth Form College; Quintin Kynaston; Sir George Monoux College; Uxbridge College; Waltham Forest College; Westminster Kingsway College; City and Guilds; London Councils Young People’s Education and Skills Board; Open College Network London; Pearson Education Ltd; TUC Unionlearn 2 Foreword It gives me great pleasure to introduce this report to you on the progression of college students in London to higher education for the years 2011 - 2014. -

Funding Values for Grant and Procured Providers

Greater London Authority Adult Education Budget Allocation Grant Values 2020 to 2021 As at 1 August 2020 Version 1.0 UKPRN Provider Name Total GLA AEB funding value (2020/21) 10004927 ACTIVATE LEARNING £107,836 10000143 BARKING & DAGENHAM LONDON BOROUGH COUNCIL £1,679,207 10000528 BARKING AND DAGENHAM COLLEGE £5,996,283 10000533 BARNET & SOUTHGATE COLLEGE £13,285,990 10000560 BASINGSTOKE COLLEGE OF TECHNOLOGY £553,104 10001465 BATH COLLEGE £127,308 10000610 BEDFORD COLLEGE £369,070 10000146 BEXLEY LONDON BOROUGH COUNCIL £2,102,127 10000863 BRENT LONDON BOROUGH COUNCIL £3,062,001 10000878 BRIDGWATER AND TAUNTON COLLEGE £247,601 10000948 BROMLEY COLLEGE OF FURTHER AND HIGHER EDUCATION £6,422,450 10003987 BROMLEY LONDON BOROUGH COUNCIL £1,629,632 10000950 BROOKLANDS COLLEGE £110,746 10000473 BUCKINGHAMSHIRE COLLEGE GROUP £546,875 10001116 CAMBRIDGE REGIONAL COLLEGE £602,322 10003988 CAMDEN LONDON BOROUGH COUNCIL £1,275,584 10001148 CAPEL MANOR COLLEGE £1,963,131 10001467 CITY OF BRISTOL COLLEGE £293,395 10008915 COMMON COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF LONDON £713,615 10001778 CROYDON COLLEGE £3,627,156 10003989 CROYDON LONDON BOROUGH COUNCIL £4,335,989 10001919 DERBY COLLEGE GROUP £698,658 10004695 DN COLLEGES GROUP £99,923 10009206 EALING LONDON BOROUGH COUNCIL £827,145 10002094 EALING, HAMMERSMITH & WEST LONDON COLLEGE £8,065,215 10002130 EAST SURREY COLLEGE £882,583 10002923 EAST SUSSEX COLLEGE GROUP £390,066 10002143 EASTLEIGH COLLEGE £3,643,450 10006570 EKC GROUP £463,805 10002638 GATESHEAD COLLEGE £561,385 10002696 GLOUCESTERSHIRE COLLEGE £207,780 -

March 2021 Transparency Report.Csv

All Invoices over £250 including VAT paid during March 2021 Payment Date Supplier Name Supplier Number Expense Area Expense Type Document No. Total (£) 01/03/2021 Manpower Direct Ltd 8338 Resident Services Health & Safety Equipment 6200327351 486,414.94 01/03/2021 Manpower Direct Ltd 8338 Resident Services Health & Safety Equipment 6200327304 230,018.20 01/03/2021 Servelec HSC 5057 Corporate Development Data centre hosting 6200325754 191,010.00 01/03/2021 Kent County Council (Kcs) 1007 Economic Growth, Housing Delivery & Cult Electricity - Service Control 6200328044 143,477.54 01/03/2021 Aston Group 910031 Capital Schemes Facilities & management services - nec 6200327208 82,436.63 01/03/2021 Kent County Council (Kcs) 1007 Economic Growth, Housing Delivery & Cult Electricity 6200328043 71,174.15 01/03/2021 J B Riney & Co Ltd 910367 Resident Services Grounds maintenance - general 6200328116 44,162.69 01/03/2021 Metropolitan Housing 21031 Families & Homes Social community care supplies and services 6200325758 40,000.00 01/03/2021 Aston Group 910031 Capital Schemes Facilities & management services - nec 6200327207 36,261.95 01/03/2021 DSI Billing Services Ltd 18435 Finance & Governance Printing and stationery 6200327772 34,370.99 01/03/2021 A New Direction 24464 Economic Growth, Housing Delivery & Cult Social community care supplies and services 6200325755 25,255.95 01/03/2021 J B Riney & Co Ltd 910367 Resident Services Grounds maintenance - general 6200328118 22,376.11 01/03/2021 The Project Centre Ltd 2308 Capital Schemes Sreet & traffic -

A-Level School Rankings 2016 (London Only)

A-level school rankings 2016 (London only) Key Gender: B – Boys, G – Girls, M – Mixed School Type: C – Comprehensive, G – Grammar, PS – Partially selective, SFC – Sixth Form College Rank School Locations Entries School Type Gender % achieving A*A+B 2 Henrietta Barnett London 389 G G 95.89 5 King's Coll London Maths London 209 G M 94.74 20 London Academy of London 567 SFC M 86.07 Excellence 29 Cardinal Vaughan London 495 C M 82.83 Memorial RC 39 St Michael's RC Grammar London 377 G G 81.17 64 Newham Collegiate SF London 405 SFC M 76.54 67 Hasmonean High London 304 C M 75.99 71 Camden for Girls London 640 C M 75.47 99 Fortismere London 585 C M 70.94 104 Mossbourne Comm London 383 C M 70.76 Academy 119 Lady Margaret London 260 C G 67.69 140 Jewish Comm Secondary London 66 C M 65.15 158 Grey Coat Hospital London 394 C M 63.2 210 Graveney London 926 PS M 58.42 274 Thomas Tallis London 411 C M 49.88 311 Haberdashers' Aske's London 369 C M 43.9 Hatcham Coll 313 St. Angela's Ursuline London 421 C M 43.47 322 Acton High London 185 C M 36.76 326 Newham SF Coll London 910 SFC M 28.46 London sixth forms & colleges Barking & Dagenham College Hackney Community College Newham Sixth Form College (NewVIc) Barnet and Southgate College Haringey Sixth Form College Redbridge College Bexley College Harrow College Richmond Upon Thames College Bromley College of Further & Higher Havering College of Further & Higher Sir George Monoux College Education Education South Thames College Brooke House Sixth Form College Havering Sixth Form College St Charles Catholic -

Contents Qualifications – Awarding Bodies

Sharing of Personal Information Contents Qualifications – Awarding Bodies ........................................................................................................... 2 UK - Universities ...................................................................................................................................... 2 UK - Colleges ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Glasgow - Schools ................................................................................................................................. 12 Local Authorities ................................................................................................................................... 13 Sector Skills Agencies ............................................................................................................................ 14 Sharing of Personal Information Qualifications – Awarding Bodies Quality Enhancement Scottish Qualifications Authority Joint Council for Qualifications (JCQ) City and Guilds General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) General Certificate of Education (GCE) Edexcel Pearson Business Development Royal Environmental Health Institute for Scotland (REHIS) Association of First Aiders Institute of Leadership and Management (ILM) Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (IOSH) UK - Universities Northern Ireland Queen's – Belfast Ulster Wales Aberystwyth Bangor Cardiff Cardiff Metropolitan South Wales -

Global Recognition List August

Accept PTE Academic: pearsonpte.com/accept Africa Egypt • Global Academic Foundation - Hosting university of Hertfordshire • Misr University for Science & Technology Libya • International School Benghazi Nigeria • Stratford Academy Somalia • Admas University South Africa • University of Cape Town Uganda • College of Business & Development Studies Accept PTE Academic: pearsonpte.com/accept August 2021 Africa Technology & Technology • Abbey College Australia • Australian College of Sport & Australia • Abbott School of Business Fitness • Ability Education - Sydney • Australian College of Technology Australian Capital • Academies Australasia • Australian Department of • Academy of English Immigration and Border Protection Territory • Academy of Information • Australian Ideal College (AIC) • Australasian Osteopathic Technology • Australian Institute of Commerce Accreditation Council (AOAC) • Academy of Social Sciences and Language • Australian Capital Group (Capital • ACN - Australian Campus Network • Australian Institute of Music College) • Administrative Appeals Tribunal • Australian International College of • Australian National University • Advance English English (AICE) (ANU) • Alphacrucis College • Australian International High • Australian Nursing and Midwifery • Apex Institute of Education School Accreditation Council (ANMAC) • APM College of Business and • Australian Pacific College • Canberra Institute of Technology Communication • Australian Pilot Training Alliance • Canberra. Create your future - ACT • ARC - Accountants Resource