Court Politics in a Federal Polity AJPS Submitted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paper Presented by the Hon. Peter Wellington MP

UI1SFTJEJOH0⒏DFST`$MFSLT` $POGFSFODF 4ZEOFZ +VMZ l4USJLJOHUIF#BMBODF*NQBSUJBMJUZBOE SFQSFTFOUBUJPOJOUIF2VFFOTMBOEQBSMJBNFOUz 1BQFSCZ)PO1FUFS8FMMJOHUPO.1 4QFBLFSPGUIF-FHJTMBUJWF"TTFNCMZ 2VFFOTMBOE1BSMJBNFOU This aim of this paper is to describe the ways in which the Speakership of the Queensland Parliament currently operates, to consider the ways in which this differs from the traditional Westminster style Parliament and indeed from previous Queensland Parliaments, and to reflect on the particular demands placed on the Speakers of small Parliaments. The Parliamentary Speaker and tradition The tradition of Speakership in the Westminster parliamentary system is a long and enduring one, commencing with the appointment of the first British Speaker, Sir Thomas Hungerford, who was appointed in 1377. From these earliest times, the Speaker has been the mouthpiece or representative of the House, speaking on behalf of the House in communicating its deliberations and decisions, to the monarchy, the Executive and also others. The Speaker represents, in a very real sense, the right of freedom of speech in the Parliament, which was hard won from a monarchical Executive centuries ago. The Parliament must constantly be prepared to maintain its right of…freedom of speech, without fear or favour.1 Amongst the numerous powers, responsibilities and functions vested in Speakers via the constitution, standing orders and conventions, and in addition to being the spokesperson of the House, the main functions of the Speaker are to preside over the debates of the -

Hon. Cameron Dick

Speech by Hon. Cameron Dick MEMBER FOR GREENSLOPES Hansard Wednesday, 22 April 2009 MAIDEN SPEECH Hon. CR DICK (Greenslopes—ALP) (Attorney-General and Minister for Industrial Relations) (7.30 pm): I start tonight by acknowledging the traditional owners of the land where this parliament stands who have served and nurtured this land for centuries. I pay tribute to them and their great role in our history. It is in this reflection of history that I begin tonight. In December 1862, three short years after the birth of our great state, whose 150th anniversary we celebrate this year, the sailing ship Conway arrived in the small Queensland settlement then known as Moreton Bay. History little records the fate of the Conway, its passengers and its crew, but one thing is known about that day in December 1862: that is the day my family arrived in Queensland and began its Queensland journey. Almost 150 years later, that journey has taken me to this place, the Queensland parliament. I stand tonight as a representative of the people in our state’s legislature, not only as a fifth-generation Queenslander but also with great humility and honour as a son of the state seat of Greenslopes, the electorate I now serve as a member of parliament. My first thanks this evening go to those people who make up the community of Greenslopes. It is a wonderful and diverse community and I look forward to serving them to the best of my ability. This electorate is very dear to my heart. It was at Holland Park, in the Greenslopes electorate, that I was raised as a boy. -

Dr Bruce Flegg MP

Queensland Government Hon Stephen Robertson MP Member for Stretton Ref [M0/10/4103] Minister for Natural Resources, Mines and Energy and Minister for Trade The Honourable John Mickel MP 17 SEP 2010 Speaker of the Legislative Assembly Parliament House George Street BRISBANE QLD 4000 Dear Mr Speaker Remainder incurpnrateii IN Icace.#. I refer you to the second reading of the. La September 2010. I believe that Dr Bruce Flegg MP, Member for Moggill and Michael Crandon MP, Member for Coomera are in breach of standing order 260 which relates to the declaration of pecuniary interest in debate and other proceedings. As indicated in the Register of Member's Interests, both members hold substantial property holdings which has land tax implications and therefore means they had a direct and material interest in speaking against the bill and of how it passed. In speaking against the bill, the members did not declare their interests at the beginning of their speech as required under section (1) of standing order 260. I would appreciate your investigation of this matter and your advice on the outcome of your deliberations. Should you have any further enquiries, please do not hesitate to contact Mr Lance McCallum, Acting Principal Advisor on telephone 3225 1861. Yours sincerely STEPHEN ROBERTSON MP Level 17 61 Mary Street Brisbane Qld 4000 PO Box 15216 City East Queensland 4002 Australia Telephone +617 3225 1861 Facsimilie +617 3225 1828 Email [email protected] HON JOHN MICKEL MP SPEAKER OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF QUEENSLAND 2 4 SEP 2010 Hon Stephen Robertson MP Minister for Natural Resources , Mines and Energy and Minister for Trade PO Box 15216 CITY EAST QLD 4002 Dear Minister I acknowledge your correspondence dated 17 September 2010, relating to Dr Bruce Flegg MP, Member for Moggill and Mr Michael Crandon MP, Member for Coomera speaking to the second reading of the Land Valuation Bill 2010 on 16 September 2010. -

QUEENSLAND January to June 2001

552 Political Chronicles QUEENSLAND January to June 2001 JOHN WANNA and TRACEY ARKLAY School of Politics and Public Policy, Griffith University Playing Smart Politics with a Divided Opposition On 23 January, after embarking on a three week "listening tour" around the state's shopping centres, jumping on public transport and swimming with sharks, the Premier Peter Beattie called an early election for 17 February 2001 — with six months of his first term remaining. The campaign ran for 26 days, the shortest permissible under the Electoral Act. The catalyst for the snap poll was the damage to Beattie's government caused by the "electoral rorts" scandal involving mainly the powerful Australian Workers' Union faction. While the initial allegations of electoral fraud had involved pre-selection battles in two Townsville seats, the repercussions were much wider engulfing the entire party and bringing down the Deputy Premier Jim Elder and two backbenchers, Grant Musgrove and Mike Kaiser. However, Beattie's political opponents were divided and Labor benefitted from a four-way split among the conservative side of politics and some other conservative independents. From the outset of the campaign, Beattie attempted to present his team as "clean" and free of rorters. He argued that the evidence to the Shepherdson inquiry (see previous Queensland Political Chronicle) demonstrated that the rorters were "just a tiny cell of people acting alone, and they have resigned or been expelled, and I don't believe anyone else is involved" (Courier-Mail, 17 January 2001). As the campaign commenced, it became clear that Labor's campaign was not just organised around the Premier; Beattie was Labor's campaign. -

Ministerial Charter of Goals - Allocation of Ministerial Responsibilities for Q2 Targets, COAG Agreements, Election Commitments and Portfolio Priorities

Page 1 of 2 From: "GRANTHAM, Julie" <IO=EDUCATIONQLDIOU=CENTRALlCN=RECIPIENT To: "ALLEN, Craig" <[email protected]> Sent: Thursday, 9 April 2009 7:30 PM Attach: AttachCharter letter att-Q2 resp by Min.doc; AttachCharter letter att-COAG.doc; AttachCharter letter att-election commitments.doc; AttachCharter letter att-previous commitments.doc; AttachCharter letter att-portfolio prioritiesdoc Subject: FW: Ministerial Charter of Goals - allocation of Ministerial responsibilities for Q2 Targets, COAG Agreements, Election Commitments and Portfolio Priorities In the attachments they are wog. If you can, just attach the bits that relate to us -----Original Message----- From: Michael Tennant [maiIto:[email protected].~ov.au~ Sent: Wednesday, April 08,2009 6:49 PM To: Michael Tennant; Dave Stewai-t; [email protected]; Colin Jensen; [email protected]; [email protected]; '[email protected]; '[email protected]; GRANTHAM, Julie; Bob Atkinson (Queensland Police); [email protected]; Mal Grierson; Gerard Bradley Cc: Bruce Wilson; Ice11 Smith; Wade Lewis; Bronwen Griffiths; Maree Fullelove; Amanda Scanlon Subject: RE: Ministerial Charter of Goals - allocation of Ministerial responsibilities for 42 Targets, COAG Agreements, Election Commitments and Portfolio Priorities Sensitivity: Confidential With attachments soily ... From: Michael Tennant Sent: Wednesday, 8 April 2009 6:48 PM To: Dave Stewart; [email protected]; Colin Jensen; [email protected]; -

Downloaded from Council’S Website At

QueenslandQueensland Government Government Gazette Gazette PP 451207100087 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ISSN 0155-9370 Vol. 359] Friday 10 February 2012 Gazette Back Issues - 2003 to 2011 To view copies of past years Gazettes please follow the Tofollowing view previous steps: years of all Gazettes, please visit our website at: 1. Go to www.bookshop.qld.gov.au www.bookshop.qld.gov.au 1.2. Click onon thethe GovernmentQueensland Crest Government that appears Crest on that the frontappears on the front page page 2. Choose the year required 3.3 Choose the week required 4. This should open the PDF copy of the combined gazette for that week (i.e. all Gazettes published for that week). 5. Should you have any problems opening the PDF, please contact [email protected] [233] Queensland Government Gazette Extraordinary PP 451207100087 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ISSN 0155-9370 Vol. 359] Friday 3 February 2012 [No. 28 Disaster Management Act 2003 NOTIFICATION OF THE DECLARATION OF A DISASTER SITUATION Department of Community Safety Brisbane, 03 February 2012 At 1.30 p.m. 03 February 2012, the Minister for Police, Corrective Services and Emergency Services approved the declaration of a Disaster Situation for the Disaster District of Charleville under Section 64 of the Disaster Management Act 2003. Hon Neil Roberts MP Minister for Police, Corrective Services and Emergency Services © The State of Queensland (SDS Publications) 2012 Copyright protects this publication. Except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act, reproduction by whatever means is prohibited without the prior written permission of SDS Publications. Inquiries should be addressed to SDS Publications, Gazette Advertising, PO Box 5506, Brendale QLD 4500. -

2011 Volume of Additional Information

Legal Affairs, Police, Corrective Services and Emergency Services Committee Estimates - 2011 Volume of Additional Information Contents Correspondence from the Leader of the House Copy of correspondence from Hon Judy Spence MP, Leader of the House to Hon John Mickel MP, Speaker, dated 17 June 2011. Copy of correspondence from Hon Judy Spence MP, Leader of the House to Hon John Mickel MP, Speaker, dated 24 June 2011. Copy of correspondence from Hon Judy Spence MP, Leader of the House to Hon John Mickel MP, Speaker, dated 25 July 2011. Minutes of meetings 17 June 2011 19 July 2011 19 July 2011 26 July 2011 Minister for Justice and Attorney-General Questions on notice and the Minister’s answers Documents tabled at the hearing Answers to questions taken on notice at the hearing Minister for Police, Corrective Services and Emergency Services Questions on notice and the Minister’s answers Documents tabled at the hearing Answers to questions taken on notice at the hearing Correspondence from the Minister dated 25 July 2011 Correspondence from the Leader of the House 17 June 2011 24 June 2011 25 July 2011 Minutes of meetings 17 June 2011 19 July 2011 19 July 2011 26 July 2011 - M I N U T E S - Minutes of a meeting of the Legal Affairs, Police, Corrective Services and Emergency Services Committee on Friday 17 June 2011 at 1.28pm Present: Hon Dean Wells MP (Chair) Mr John-Paul Langbroek MP (Deputy Chair) Mrs Julie Attwood MP Mr Jarrod Bleijie MP Mr Chris Foley MP Mrs Betty Kiernan MP (until 1.59pm) Apologies: In attendance: Ms Barbara Stone MP Mr Stephen Finnimore, Research Director Ms Amanda Honeyman, Principal Research Officer Hearing schedule: At the meeting, members were provided with two draft hearing schedule options, and copies of all departmental structures, statutory authorities and senior officers of the departments. -

Annual Report 2010

Office of the Governor Annual Report 2010 - 2011 To obtain information about the content of this report, please contact: Air Commodore Mark Gower OAM (Retd) Official Secretary Office of the Governor, Queensland GPO Box 434 Brisbane Qld 4001 Telephone: (07) 3858 5700 Facsimile: (07) 3858 5701 Email: [email protected] Information about the activities of the Queensland Governor and the operations of the Office of the Governor is available at the following internet address: www.govhouse.qld.gov.au Internet annual report: www.govhouse.qld.gov.au/news_media/annual_reports.aspx Copyright and ISSN © The State of Queensland (Office of the Governor) 2011. Copyright protects this publication except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act. Reproduction by whatever means is prohibited without the prior written permission of the accountable officer. ISSN 1837 – 2775 Aim of Report The Office of the Governor Annual Report 2010–2011 is an integral part of the Office of the Governor’s corporate governance framework and describes the achievements, performance, outlook and financial position of the Office for the financial year. The Annual Report is a key accountability document and the principal way in which the Office reports on activities and provides a full and complete picture of its performance to Parliament and the wider community. The Report covers the objectives, activities and performance of the Office during the period 1 July 2010 to 30 June 2011 and includes information and images that illustrate the many activities which the Office undertakes to provide personal, administrative and logistic support to the Governor and manage the Government House Estate. -

Do You Live in One of These ALP Electorates? Please Sign One of Our Postcards and Send It to Your Local ALP Member

Do you live in one of these ALP electorates? Please sign one of our postcards and send it to your local ALP member. Electorates marked in bold are marginal seats & even more important to target! Algester STRUTHERS, Karen Mackay MULHERIN, Tim Ashgrove JONES, Kate Mansfield REEVES, Phil Aspley BARRY, Bonny Mount Coot-tha FRASER, Andrew Barron River WETTENHALL, Steve Mount Gravatt SPENCE, Judy Brisbane Cent. Grace, Grace Mount Isa KIERNAN, Betty Broadwater CROFT, Peta-Kaye (PK) Mt Ommaney ATTWOOD, Julie Bulimba PURCELL, Pat Mudgeeraba REILLY, Dianne Bundamba MILLER, Jo-Ann Mulgrave PITT, Warren Burleigh SMITH, Christine Mundingburra NELSON-CARR, Lindy Cairns BOYLE, Desley Murrumba WELLS, Dean Capalaba CHOI, Michael Nudgee ROBERTS, Neil Chatsworth BOMBOLAS, Chris Pumicestone SULLIVAN, Carryn Cleveland WEIGHTMAN, Phil Redcliffe van LITSENBURG, Lillian Cook O’BRIEN, Jason Redlands ENGLISH, John Everton WELFORD, Rod Rockhampton SCHWARTEN, Robert E Ferny Grove WILSON, Geoff Sandgate DARLING, Vicky Fitzroy PEARCE, Jim South Brisbane BLIGH, Anna Gaven GRAY, Phil Southport LAWLOR, Peter Glass House MALE, Carolyn Springwood STONE, Barbara Greenslopes FENLON, Gary Stafford HINCHLIFFE, Stirling Hervey Bay McNAMARA, Andrew Stretton ROBERTSON, Stephen Inala PALASZCZUK, Annastacia Thuringowa WALLACE, Craig Ipswich NOLAN, Rachel Toowoomba Nth SHINE, Kerry Ipswich West WENDT, Wayne Townsville REYNOLDS, Mike Kallangur HAYWARD, Ken Waterford MOORHEAD, Evan Keppel HOOLIHAN, Paul A. Whitsunday JARRATT, Jan Kurwongbah LAVARCH, Linda Woodridge SCOTT, Desley Logan -

05.01.07Combined.Pdf

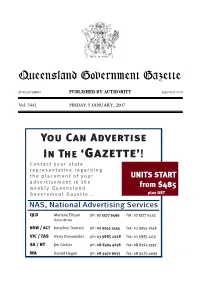

QueenslandQueensland Government Government Gazette Gazette PP 451207100087 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ISSN 0155-9370 Vol. 344] FRIDAY, 5 JANUARY, 2007 You Can Advertise In The ‘Gazette’! Contact your state representative regarding the placement of your UNITS START advertisement in the from $485 weekly Queensland Government Gazette... plus GST NAS, National Advertising Services QLD Marlene Ellison ph: 07 5577 9499 fax: 07 5577 9433 Horne Media NSW / ACT Jonathon Tremain ph: 02 9955 3545 fax: 02 9955 3646 VIC / TAS Harry Damoulakis ph: 03 9885 2928 fax: 03 9885 1179 SA / NT Jim Girdler ph: 08 8364 4678 fax: 08 8364 5557 WA Harold Hogan ph: 08 9470 6655 fax: 08 9470 4699 [1973] Queensland Government Gazette EXTRAORDINARY PP 451207100087 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ISSN 0155-9370 Vol. 343] FRIDAY, 22 DECEMBER, 2006 [No. 123 NOTICE Premier’s Office Brisbane, 21 December 2006 Her Excellency the Governor directs it to be notified that, acting under the provisions of the Constitution of Queensland 2001, she has appointed the Honourable Paul Thomas Lucas MP, Minister for Transport and Main Roads to act as, and to perform all of the functions and exercise all of the powers of, Minister for State Development, Employment and Industrial Relations from 19 January 2007 until the Honourable Reginald John Mickel MP returns to duty. PETER BEATTIE MP PREMIER AND MINISTER FOR TRADE NOTICE Premier’s Office Brisbane, 21 December 2006 Her Excellency the Governor directs it to be notified that, acting under the provisions of the Constitution of Queensland 2001, she has appointed the Honourable Rodney Jon Welford MP, Minister for Education and Training Minister for the Arts to act as, and to perform all of the functions and exercise all of the powers of, Minister for Health from 1 January 2007 until the Honourable Stephen Robertson MP returns to Queensland. -

Political Chronicles

Australian Journal of Politics and History: Volume 54, Number 2, 2008, pp. 289-341. Political Chronicles Commonwealth of Australia July to December 2007 JOHN WANNA The Australian National University and Griffith University The Stage, the Players and their Exits and Entrances […] All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players; They have their exits and their entrances; [William Shakespeare, As You Like It] In the months leading up to the 2007 general election, Prime Minister John Howard waited like Mr Micawber “in case anything turned up” that would restore the fortunes of the Coalition. The government’s attacks on the Opposition, and its new leader Kevin Rudd, had fallen flat, and a series of staged events designed to boost the government’s stocks had not translated into electoral support. So, as time went on and things did not improve, the Coalition government showed increasing signs of panic, desperation and abandonment. In July, John Howard had asked his party room “is it me” as he reflected on the low standing of the government (Australian, 17 July 2007). Labor held a commanding lead in opinion polls throughout most of 2007 — recording a primary support of between 47 and 51 per cent to the Coalition’s 39 to 42 per cent. The most remarkable feature of the polls was their consistency — regularly showing Labor holding a 15 percentage point lead on a two-party-preferred basis. Labor also seemed impervious to attack, and the government found it difficult to get traction on “its” core issues to narrow the gap. -

Queensland January to June 2004

Political Chronicles 605 Queensland January to June 2004 JOHN WANNA Political Science Program, Australian National University, and Politics and Public Policy, Griffith University A Re- Pete Landslide at the 2004 State Election Premier Peter Beattie caught the opposition completely by surprise announcing the state election on 14 January, while most Queenslanders were still on holiday. The Opposition Leader, Lawrence Springborg, working on his farm, raced back to Brisbane, while the Liberals' Leader, Bob Quinn, caught an early flight interrupting his family holiday in Sydney. Just as with the 2001 poll, Beattie's timing meant the campaign would occur over the summer break with few paying attention to politics. Beattie's repeat of a successful tactic reeked of opportunism. Beattie brought on the snap poll in an attempt to clear the air over systemic maladministration exposed in the Families Department. The department charged with protecting children had failed to act in hundreds of cases of child abuse — especially children in foster case and particularly indigenous children. The public inquiry held by the Crime and Misconduct Commission (CMC) in 2003 discovered a culture of cover- up in the besieged department. Even when given evidence of cases of sexual abuse it felt powerless to act and often did not forward matters to the police. The CMC produced an interim report in January 2004 citing 110 recommendations for change. Beattie admitted publicly that both his government and the department "had failed" and that he would provide funding to implement the reforms (Courier-Mail, 7 January 2004). He stated his intention of seeking a mandate to fix the foster care crisis.