1 Case Study: Lise Meitner 1944 Nobel Prize in Chemistry Awarded

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antony Hewish

PULSARS AND HIGH DENSITY PHYSICS Nobel Lecture, December 12, 1974 by A NTONY H E W I S H University of Cambridge, Cavendish Laboratory, Cambridge, England D ISCOVERY OF P U L S A R S The trail which ultimately led to the first pulsar began in 1948 when I joined Ryle’s small research team and became interested in the general problem of the propagation of radiation through irregular transparent media. We are all familiar with the twinkling of visible stars and my task was to understand why radio stars also twinkled. I was fortunate to have been taught by Ratcliffe, who first showed me the power of Fourier techniques in dealing with such diffraction phenomena. By a modest extension of existing theory I was able to show that our radio stars twinkled because of plasma clouds in the ionosphere at heights around 300 km, and I was also able to measure the speed of ionospheric winds in this region (1) . My fascination in using extra-terrestrial radio sources for studying the intervening plasma next brought me to the solar corona. From observations of the angular scattering of radiation passing through the corona, using simple radio interferometers, I was eventually able to trace the solar atmo- sphere out to one half the radius of the Earth’s orbit (2). In my notebook for 1954 there is a comment that, if radio sources were of small enough angular size, they would illuminate the solar atmosphere with sufficient coherence to produce interference patterns at the Earth which would be detectable as a very rapid fluctuation of intensity. -

Chapter 6 the Aftermath of the Cambridge-Vienna Controversy: Radioactivity and Politics in Vienna in the 1930S

Trafficking Materials and Maria Rentetzi Gendered Experimental Practices Chapter 6 The Aftermath of the Cambridge-Vienna Controversy: Radioactivity and Politics in Vienna in the 1930s Consequences of the Cambridge-Vienna episode ranged from the entrance of other 1 research centers into the field as the study of the atomic nucleus became a promising area of scientific investigation to the development of new experimental methods. As Jeff Hughes describes, three key groups turned to the study of atomic nucleus. Gerhard Hoffman and his student Heinz Pose studied artificial disintegration at the Physics Institute of the University of Halle using a polonium source sent by Meyer.1 In Paris, Maurice de Broglie turned his well-equipped laboratory for x-ray research into a center for radioactivity studies and Madame Curie started to accumulate polonium for research on artificial disintegration. The need to replace the scintillation counters with a more reliable technique also 2 led to the extensive use of the cloud chamber in Cambridge.2 Simultaneously, the development of electric counting methods for measuring alpha particles in Rutherford's laboratory secured quantitative investigations and prompted Stetter and Schmidt from the Vienna Institute to focus on the valve amplifier technique.3 Essential for the work in both the Cambridge and the Vienna laboratories was the use of polonium as a strong source of alpha particles for those methods as an alternative to the scintillation technique. Besides serving as a place for scientific production, the laboratory was definitely 3 also a space for work where tasks were labeled as skilled and unskilled and positions were divided to those paid monthly and those supported by grant money or by research fellowships. -

The Exploration of the Unknown

The exploration of the unknown K. I. Kellermann1 National Radio Astronomy Observatory Charlottesville, VA, U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected] J. M. Cordes Cornell University Ithaca, NY E-mail: [email protected] R.D. Ekers CSIRO Sydney, Australia E-mail: [email protected] J. Lazio Naval Research Lab Washington, D.C., USA E-mail: [email protected] Peter Wilkinson Jodrell Bank Center for Astrophsyics Manchester, UK E-mail: [email protected] Accelerating the Rate of Astronomical Discovery - sps5 Rio de Janeiro, Brazil August 11–14 2009 1 Speaker Copyright owned by the author(s) under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike Licence. http://pos.sissa.it Summary The discovery of cosmic radio emission by Karl Jansky in the course of searching for the source of interference to telephone communications and the instrumental advances which followed, have led to a series of new paradigm changing astronomical discoveries. These include the non-thermal emission from stars and galaxies, electrical storms on the Sun and Jupiter, radio galaxies, AGN, quasars and black holes, pulsars and neutron stars, the CMB, interstellar molecules and giant molecular clouds; the anomalous rotation of Venus and Mercury, cosmic masers, extra-solar planets, precise tests of gravitational bending, gravitational lensing, the first experimental evidence for gravitational radiation, and the first observational evidence for cosmic evolution. These discoveries, which to a large extent define much of modern astrophysical research, have resulted in eight Nobel Prize winners. They were the result of the right people being in the right place at the right time using powerful new instruments, which in many cases they had designed and built. -

Der Mythos Der Deutschen Atombombe

Langsame oder schnelle Neutronen? Der Mythos der deutschen Atombombe Prof. Dr. Manfred Popp Karlsruher Institut für Technologie Ringvorlesung zum Gedächtnis an Lise Meitner Freie Universität Berlin 29. Oktober 2018 In diesem Beitrag geht es zwar um Arbeiten zur Kernphysik in Deutschland während des 2.Weltkrieges, an denen Lise Meitner wegen ihrer Emigration 1938 nicht teilnahm. Es geht aber um das Thema Kernspaltung, zu dessen Verständnis sie wesentliches beigetragen hat, um die Arbeit vieler, gut vertrauter, ehemaliger Kollegen und letztlich um das Schicksal der deutschen Physik unter den Nationalsozialisten, die ihre geistige Heimat gewesen war. Da sie nach dem Abwurf der Bombe auf Hiroshima auch als „Mutter der Atombombe“ diffamiert wurde, ist es ihr gewiss nicht gleichgültig gewesen, wie ihr langjähriger Partner und Freund Otto Hahn und seine Kollegen während des Krieges mit dem Problem der möglichen Atombombe umgegangen sind. 1. Stand der Geschichtsschreibung Die Geschichtsschreibung über das deutsche Uranprojekt 1939-1945 ist eine Domäne amerikanischer und britischer Historiker. Für die deutschen Geschichtsforscher hatte eines der wenigen im Ergebnis harmlosen Kapitel der Geschichte des 3. Reiches keine Priorität. Unter den alliierten Historikern hat sich Mark Walker seit seiner Dissertation1 durchgesetzt. Sein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Kaiser Wilhelm-Gesellschaft im 3. Reich beginnt mit den Worten: „The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics is best known as the place where Werner Heisenberg worked on nuclear weapons for Hitler.“2 Im Jahr 2016 habe ich zum ersten Mal belegt, dass diese Schlussfolgerung auf Fehlinterpretationen der Dokumente und auf dem Ignorieren physikalischer Fakten beruht.3 Seit Walker gilt: Nicht an fehlenden Kenntnissen sei die deutsche Atombombe gescheitert, sondern nur an den ökonomischen Engpässen der deutschen Kriegswirtschaft: „An eine Bombenentwicklung wäre [...] auch bei voller Unterstützung des Regimes nicht zu denken gewesen. -

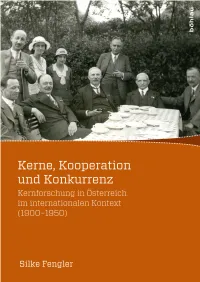

Kerne, Kooperation Und Konkurrenz. Kernforschung In

Wissenschaft, Macht und Kultur in der modernen Geschichte Herausgegeben von Mitchell G. Ash und Carola Sachse Band 3 Silke Fengler Kerne, Kooperation und Konkurrenz Kernforschung in Österreich im internationalen Kontext (1900–1950) 2014 Böhlau Verlag Wien Köln Weimar The research was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) : P 19557-G08 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Datensind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Umschlagabbildung: Zusammentreffen in Hohenholte bei Münster am 18. Mai 1932 anlässlich der 37. Hauptversammlung der deutschen Bunsengesellschaft für angewandte physikalische Chemie in Münster (16. bis 19. Mai 1932). Von links nach rechts: James Chadwick, Georg von Hevesy, Hans Geiger, Lili Geiger, Lise Meitner, Ernest Rutherford, Otto Hahn, Stefan Meyer, Karl Przibram. © Österreichische Zentralbibliothek für Physik, Wien © 2014 by Böhlau Verlag Ges.m.b.H & Co. KG, Wien Köln Weimar Wiesingerstraße 1, A-1010 Wien, www.boehlau-verlag.com Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Werk ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist unzulässig. Lektorat: Ina Heumann Korrektorat: Michael Supanz Umschlaggestaltung: Michael Haderer, Wien Satz: Michael Rauscher, Wien Druck und Bindung: Prime Rate kft., Budapest Gedruckt auf chlor- und säurefrei gebleichtem Papier Printed in Hungary ISBN 978-3-205-79512-4 Inhalt 1. Kernforschung in Österreich im Spannungsfeld von internationaler Kooperation und Konkurrenz ....................... 9 1.1 Internationalisierungsprozesse in der Radioaktivitäts- und Kernforschung : Eine Skizze ...................... 9 1.2 Begriffsklärung und Fragestellungen ................. 10 1.2.2 Ressourcenausstattung und Ressourcenverteilung ......... 12 1.2.3 Zentrum und Peripherie ..................... 14 1.3 Forschungsstand ........................... 16 1.4 Quellenlage ............................. -

Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Werner Heisenberg And

MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science PREPRINT 203 (2002) Horst Kant Werner Heisenberg and the German Uranium Project Otto Hahn and the Declarations of Mainau and Göttingen Werner Heisenberg and the German Uranium Project* Horst Kant Werner Heisenberg’s (1901-1976) involvement in the German Uranium Project is the most con- troversial aspect of his life. The controversial discussions on it go from whether Germany at all wanted to built an atomic weapon or only an energy supplying machine (the last only for civil purposes or also for military use for instance in submarines), whether the scientists wanted to support or to thwart such efforts, whether Heisenberg and the others did really understand the mechanisms of an atomic bomb or not, and so on. Examples for both extreme positions in this controversy represent the books by Thomas Powers Heisenberg’s War. The Secret History of the German Bomb,1 who builds up him to a resistance fighter, and by Paul L. Rose Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project – A Study in German Culture,2 who characterizes him as a liar, fool and with respect to the bomb as a poor scientist; both books were published in the 1990s. In the first part of my paper I will sum up the main facts, known on the German Uranium Project, and in the second part I will discuss some aspects of the role of Heisenberg and other German scientists, involved in this project. Although there is already written a lot on the German Uranium Project – and the best overview up to now supplies Mark Walker with his book German National Socialism and the quest for nuclear power, which was published in * Paper presented on a conference in Moscow (November 13/14, 2001) at the Institute for the History of Science and Technology [àÌÒÚËÚÛÚ ËÒÚÓËË ÂÒÚÂÒÚ‚ÓÁ̇ÌËfl Ë ÚÂıÌËÍË ËÏ. -

Martin Ryle (1918–1984)

ARTICLE-IN-A-BOX Martin Ryle (1918–1984) Martin Ryle was one of the pioneers of the field of radio astronomy which made rapid progress in the decades immediately following the Second World War. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for developing the technique known as ‘aperture synthesis’. This overcame what appeared to be a fundamental limitation of using radio waves. The smallest angle θmin (in ra- dians) at which details can be made out in an image of the sky made by a telescope depends on its diameter D and the wavelength λ. This is called the angular resolution and is given by the famous equation θmin = λ/D. Any finer detail such as the separation of two stars get blurred out. At a radio wavelength of 0.5 metres and a telescope of diameter of 50 metres, 1 this comes out to be 100 radian or a little more than half a degree – the size of the moon as seen from the Earth. The early pictures of the sky in radio waves were very crude compared to those made with visible light, typical wavelength 0.5 micrometres, a million times smaller. Making a radio dish of size even 100 times an optical telescope mirror would still leave radio pictures ten thousand times poorer than those made with visible light. Aperture synthesis broke this barrier, and today radio astronomy produces the sharpest images at any wavelength! The background to the emergence of radio astronomy, and this particular technique are explained in the article by Chengalur in this issue (p.165). -

Hitler's Uranium Club, the Secret Recordings at Farm Hall

HITLER’S URANIUM CLUB DER FARMHALLER NOBELPREIS-SONG (Melodie: Studio of seiner Reis) Detained since more than half a year Ein jeder weiss, das Unglueck kam Sind Hahn und wir in Farm Hall hier. Infolge splitting von Uran, Und fragt man wer is Schuld daran Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. The real reason nebenbei Die energy macht alles waermer. Ist weil we worked on nuclei. Only die Schweden werden aermer. Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. Die nuclei waren fuer den Krieg Auf akademisches Geheiss Und fuer den allgemeinen Sieg. Kriegt Deutschland einen Nobel-Preis. Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. Wie ist das moeglich, fragt man sich, In Oxford Street, da lebt ein Wesen, The story seems wunderlich. Die wird das heut’ mit Thraenen lesen. Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. Die Feldherrn, Staatschefs, Zeitungsknaben, Es fehlte damals nur ein atom, Ihn everyday im Munde haben. Haett er gesagt: I marry you madam. Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. Even the sweethearts in the world(s) Dies ist nur unsre-erste Feier, Sie nennen sich jetzt: “Atom-girls.” Ich glaub die Sache wird noch teuer, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. -

Nobel Laureates

Nobel Laureates Over the centuries, the Academy has had a number of Nobel Prize winners amongst its members, many of whom were appointed Academicians before they received this prestigious international award. Pieter Zeeman (Physics, 1902) Lord Ernest Rutherford of Nelson (Chemistry, 1908) Guglielmo Marconi (Physics, 1909) Alexis Carrel (Physiology, 1912) Max von Laue (Physics, 1914) Max Planck (Physics, 1918) Niels Bohr (Physics, 1922) Sir Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman (Physics, 1930) Werner Heisenberg (Physics, 1932) Charles Scott Sherrington (Physiology or Medicine, 1932) Paul Dirac and Erwin Schrödinger (Physics, 1933) Thomas Hunt Morgan (Physiology or Medicine, 1933) Sir James Chadwick (Physics, 1935) Peter J.W. Debye (Chemistry, 1936) Victor Francis Hess (Physics, 1936) Corneille Jean François Heymans (Physiology or Medicine, 1938) Leopold Ruzicka (Chemistry, 1939) Edward Adelbert Doisy (Physiology or Medicine, 1943) George Charles de Hevesy (Chemistry, 1943) Otto Hahn (Chemistry, 1944) Sir Alexander Fleming (Physiology, 1945) Artturi Ilmari Virtanen (Chemistry, 1945) Sir Edward Victor Appleton (Physics, 1947) Bernardo Alberto Houssay (Physiology or Medicine, 1947) Arne Wilhelm Kaurin Tiselius (Chemistry, 1948) - 1 - Walter Rudolf Hess (Physiology or Medicine, 1949) Hideki Yukawa (Physics, 1949) Sir Cyril Norman Hinshelwood (Chemistry, 1956) Chen Ning Yang and Tsung-Dao Lee (Physics, 1957) Joshua Lederberg (Physiology, 1958) Severo Ochoa (Physiology or Medicine, 1959) Rudolf Mössbauer (Physics, 1961) Max F. Perutz (Chemistry, 1962) -

Ieee-Level Awards

IEEE-LEVEL AWARDS The IEEE currently bestows a Medal of Honor, fifteen Medals, thirty-three Technical Field Awards, two IEEE Service Awards, two Corporate Recognitions, two Prize Paper Awards, Honorary Memberships, one Scholarship, one Fellowship, and a Staff Award. The awards and their past recipients are listed below. Citations are available via the “Award Recipients with Citations” links within the information below. Nomination information for each award can be found by visiting the IEEE Awards Web page www.ieee.org/awards or by clicking on the award names below. Links are also available via the Recipient/Citation documents. MEDAL OF HONOR Ernst A. Guillemin 1961 Edward V. Appleton 1962 Award Recipients with Citations (PDF, 26 KB) John H. Hammond, Jr. 1963 George C. Southworth 1963 The IEEE Medal of Honor is the highest IEEE Harold A. Wheeler 1964 award. The Medal was established in 1917 and Claude E. Shannon 1966 Charles H. Townes 1967 is awarded for an exceptional contribution or an Gordon K. Teal 1968 extraordinary career in the IEEE fields of Edward L. Ginzton 1969 interest. The IEEE Medal of Honor is the highest Dennis Gabor 1970 IEEE award. The candidate need not be a John Bardeen 1971 Jay W. Forrester 1972 member of the IEEE. The IEEE Medal of Honor Rudolf Kompfner 1973 is sponsored by the IEEE Foundation. Rudolf E. Kalman 1974 John R. Pierce 1975 E. H. Armstrong 1917 H. Earle Vaughan 1977 E. F. W. Alexanderson 1919 Robert N. Noyce 1978 Guglielmo Marconi 1920 Richard Bellman 1979 R. A. Fessenden 1921 William Shockley 1980 Lee deforest 1922 Sidney Darlington 1981 John Stone-Stone 1923 John Wilder Tukey 1982 M. -

Nobel Voices Video History Project, 2000-2001

Nobel Voices Video History Project, 2000-2001 Interviewee: Anthony Hewish Interviewer: Neil Hollander Date: February 8, 2000 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History HOLLANDER: If you don’t mind, I’d like you to begin briefly by giving us your name and then briefly identifying yourself. HEWISH: Well, I’m Anthony Hewish. I’m now Emeritus Professor of Radio Astronomy in the University of Cambridge, and I’m aged seventy-six. I’m still active in research, but, of course, I’m no longer head of the research group which I directed towards the end of my career. HOLLANDER: Well, let’s go way back. Can you remember, can you identify the moment as a child, perhaps, as a youth, that you first became interested in science? HEWISH: Oh, that was very early indeed. I think if I look back, I must have been about six years old, maybe seven years old, and I was playing with a few wires and electric batteries and torchlight bulbs, and I discovered for myself that if I put one of the wires from the battery onto a big—we had a big brass tray, and I discovered that if I connected one of my wires onto the tray, then I could touch this bulb down anywhere on the tray, and it would light up. That was the kind of discovery I made for myself, and I suddenly realized, “Hey, you know, this whole tray here is acting like a wire. That’s pretty interesting.” It’s pretty elementary science now, but, you know, in those days when you always used wires to connect things up, the fact that you could use this whole tray, metal tray, and you could put the bulb down anywhere, you know, that struck me as really quite a nice thing. -

Sir Martin Ryle Brighton, UK, 27 Sep

Sir Martin Ryle Brighton, UK, 27 Sep. 1918 - Cambridge, UK, 14 Oct. 1984 Title Professor of Radioastronomy, University of Cambridge, UK. Nobel laureate in Physics, 1974 Nomination 2 Dec. 1975 Commemoration – Sir Martin Ryle, who died on 14th October 1984 at the age of 66, was one of the most outstanding figures in British science of the present century. He was born into a distinguished academic family, his father being, first, Regius Professor of Physics in Cambridge and then Professor of Social Medicine in Oxford. Gilbert Ryle, the eminent Professor of Metaphysical Philosophy, was Martin's cousin. Martin Ryle himself was a student at Christ Church, Oxford, from where he graduated with First Class Honours in Physics in 1939 just before the beginning of the last war. At the outbreak of war Ryle joined a brilliant team of electronic scientists who were concerned with research in the field of radar and in particular with the development of airborne radar systems. When war was over Ryle joined the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, where he started to investigate the emission of radio waves, which James Hey had discovered during the war as coming from the sun and as affecting radar networks. Not many scientists believed at the time that the sun was really the source of radio emission, but if it was, where exactly did the radio waves come from? In the 1940s radio aerials operating in the metre waveband had beam widths of 10 degrees or more. They could well detect radio emission from the Sun as a whole, which is half a degree wide, but they were quite unable to pinpoint possible sources such as sunspots, which Galileo had easily spotted with his tiny optical telescope more than 300 years earlier.