The Railway in Nineteenth-Century London Ralph Harrington, University of York

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U DX251 Account Books of John Hudson of Howsham 1799

Hull History Centre: Account books of John Hudson of Howsham U DX251 Account books of John Hudson of Howsham 1799 Biographical Background: John Hudson of Howsham, a Scarborough merchant and farmer, was probably born in 1756 and died in 1808. He married an Elizabeth Ruston and had seven children, including two daughters and five sons. His youngest son, George Hudson, later became known as 'The Railway King'. George Hudson was born in March 1800 and died on 14 December 1871. He became famous as a English railway financier, earning the nickname "The Railway King”. He initially apprenticed as a draper at Bell and Nicholson in York. In 1820 he was taken on by the firm as a tradesman and given a share of the business. By 1827 it was the largest business in York. Also in 1827, he inherited £30,000 from his great uncle. Hudson played a major part in establishing the York Union Banking Company and he first became Lord Mayor in York in 1837. He was Lord Mayor three times as well as deputy-lieutenant for Durham and Conservative Member of Parliament for Sunderland from August 1845 until 1859. Hudson was instrumental in the expansion of the railways across England and in the Railway Clearing House (1842). He amalgamated the North Midland, the Midland Counties Railway and the Birmingham & Derby Junction Railway in 1844 to become the Midland Railway. He initiated the Newcastle and Darlington line in 1841 and with George Stephenson, planned and carried out the extension of the York & North Midland Railway to Newcastle. By 1844 he had control of over a thousand miles of railway. -

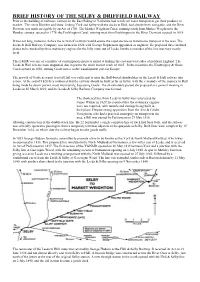

Brief History of the Selby & Driffield Railway

BRIEF HISTORY OF THE SELBY & DRIFFIELD RAILWAY Prior to the building of railways, farmers in the East Riding of Yorkshire had to rely on water transport to get their produce to market. The rivers Humber and Ouse, linking York and Selby with the docks at Hull, had always been navigable, and the River Derwent was made navigable by an Act of 1701. The Market Weighton Canal, running south from Market Weighton to the Humber estuary, opened in 1778; the Pocklington Canal, running west from Pocklington to the River Derwent, opened in 1818. It was not long, however, before the arrival of railways would ensure the rapid decline in waterborne transport in the area. The Leeds & Hull Railway Company was formed in 1824 with George Stephenson appointed as engineer. He proposed three inclined planes to be worked by three stationary engines for the hilly route out of Leeds, but the remainder of the line was very nearly level. This L&HR was one of a number of contemporary projects aimed at linking the east and west sides of northern England. The Leeds & Hull scheme soon stagnated, due in part to the stock market crash of 1825. In the meantime the Knottingley & Goole Canal opened in 1826, turning Goole into a viable transhipment port for Europe. The growth of Goole as a port to rival Hull was sufficient to spur the Hull-based shareholders of the Leeds & Hull railway into action. At the end of 1828 they motioned that the railway should be built as far as Selby, with the remainder of the journey to Hull being made by steam packet, most importantly, bypassing Goole. -

'Supplement to the London Gazette, 30 March, 1920. 3839

'SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 30 MARCH, 1920. 3839 Herbert William Horridge, Esq. George Hudson, Esq. Acting First-Class Clerk, Finance Branch, Acting Constructor, H.M. Dockyard, Ministry of Pensions. Devonport. Mjiasi Florence Gertrude Horsburgh. Joe Hudson, Esq. Supervisor, 'Chelsea National Kitchens, Vice-'Chairman, Shipley Local War Pen- Ministry of Food. sions Committee. Lambert Gordon Horsburgh, Esq. Russell Hudson, Esq. Assistant .Superintending Engineer, De- Section Director, Gauges Department, partment of Engineering, Ministry of Muni- Ministry of Munitions. tions. Samuel Hudson, Esq. •Captain James Horsfield. Commander, Burnley Special Constabu- Master, S.S. " Claymont." lary. .Robert Lund Horsfield, Esq. Miss Amy Christine Adela Huggins. General Manager, Walsall Corporation - Port of Spain. Tramways. Elizabeth Annie, Mrs. Huggins. Ernest George Horsman, Esq. Honorary Treasurer, Gravesend Prisoners Timber -Supply Department, Board of •of War Fund. Trade. Albert Hughes, Esq. William Christian Hothersall, Esq. Chief Clerk, Buckingham Territorial Force Research Chemist, Research Department, Association. Royal Arsenal, Woolwich. Charles Hughes, Esq. •Charles Edward George House, Esq. Services in connection with War Refugees First-Class Trade Officer, Overseas Trade at Peterborough. (Development and Intelligence) Department, Miss Dulcie Hughes. Board of Trade. V.A.D., Head Cook, No. 8 Red Cross Captain the Honourable Bernard Edward Hospital, Boulogne Fitzalan. Howard. Frederick Richard Hughes, Esq. Central Establishment Department, Minis- Honorary Secretary, Bury St. Edmunds try of Munitions. War Savings Committee. Francis Howard, Esq John Gwilym Hughes, Esq. House Secretary to His Majesty's Ambas- Deputy Food Commissioner, North Wales sador in Paris. Division, Ministry of Food. .Mary, Mrs, Howard. Captain Richard Lloyd Hughes. Representative Member for Bedford on Master, S.S. -

Notices and Proceedings for the North East of England 2485

Office of the Traffic Commissioner (North East of England) Notices and Proceedings Publication Number: 2485 Publication Date: 23/07/2021 Objection Deadline Date: 13/08/2021 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (North East of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Website: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 23/07/2021 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] Remember to keep your bus registrations up to date - check yours on https://www.gov.uk/manage-commercial-vehicle-operator-licence-online PLEASE NOTE THE PUBLIC COUNTER IS CLOSED AND TELEPHONE CALLS WILL NO LONGER BE TAKEN AT HILLCREST HOUSE UNTIL FURTHER NOTICE The Office of the Traffic Commissioner is currently running an adapted service as all staff are currently working from home in line with Government guidance on Coronavirus (COVID-19). Most correspondence from the Office of the Traffic Commissioner will now be sent to you by email. There will be a reduction and possible delays on correspondence sent by post. The best way to reach us at the moment is digitally. Please upload documents through your VOL user account or email us. There may be delays if you send correspondence to us by post. At the moment we cannot be reached by phone. -

Railway Heritage Trail

Exploring York’s Railway Heritage Life before the Transport Revolution York has been a hub of transport communications since the Romans established the city in AD71, linking it to an efficient road system and making use of its waterways. But until the railways were established in the early part of the nineteenth century, people could only travel as fast as their feet or a horse could take them. In the early eighteenth century, a stagecoach journey from York to London took 3 to 4 days, though by the end of the century innovations in road construction and coach design had shortened the journey-time to around 36 hours. Early Development of the Railways By chance Hudson met George Stephenson and persuaded him In 1804 Richard Trevithick demonstrated that a mobile steam that a railway from York to the coalfields near Selby would be engine powered by coal could run on a permanent way of iron. profitable. The first railway connecting York to the Leeds and With so many horses enlisted in the Napoleonic wars, horse Selby line was opened in 1839 and by 1841, York was linked all power was becoming more expensive. North of Newcastle upon the way to London. Hudson pressed on with more speculation, Tyne a mining engineer called George Stephenson opening the line from York to Newcastle-upon-Tyne in 1844 and, This is York experimented with by then owning over 1,000 miles of track, he gained the title ‘The steam power. If coal Railway King’. Eventually, however, the bubble burst, profits fell Exploring York’s Railway Heritage could be fed to a and investigations began into Hudson’s misuse of shareholders’ mobile steam engine money. -

Local Geography Context – (2) History Basics Timeline the Railway in Skelmanthorpe Appendix – Background Notes on the Four Major Companies in the Area Abbreviations

RAILWAYS AROUND SKELMANTHORPE CONTENTS Context – (1) local geography Context – (2) history basics Timeline The railway in Skelmanthorpe Appendix – Background notes on the four major companies in the area Abbreviations CONTEXT – (1) LOCAL GEOGRAPHY A glance at the railway map of Britain in, say, 1914 shows the country well covered apart from gaps in areas such as the Scottish Highlands, the network being especially dense in major cities and in industrial, especially coal mining, areas. Skelmanthorpe lies on the western edge of such an area, extending southwards through the Yorkshire/Nottinghamshire coalfield and its associated cities. If we focus in on the former West Riding area (covering Leeds / Bradford / Huddersfield / Sheffield / Wakefield / Pontefract) we could describe its rail network as both dense and complicated. While there’s nothing special in its density - plenty of other areas can match it – it is arguably unusually complex, a product both of history and geography. In confirmation of this, six out of the eight largest pre-Grouping companies (measured a little crudely by the number of locomotives owned) had a presence in the West Riding area (though the North Eastern was confined to the north and east of Leeds). Only London had a comparable number, while Greater Manchester, for instance, had only four of the eight, or the West Midlands three. Even the immediate local area involves three of the largest - the London & North Western (ranking 1) through Huddersfield plus the Kirkburton branch, the Great Central (ranking 7) through Penistone and the Lancashire & Yorkshire (ranking 5) with the Huddersfield- Penistone line and its three branches. -

6-3 Might-Have-Beens

Some English Railway Might-Have-Beens Charles Klapper The 50th Anniversary Journal, published in May 2004, contained the extracts dealing with Wales, the Border Counties and Scotland from Klapper’s paper ‘Some Railway Might-Have-Beens’, which had been presented to a meeting of the Society on 18 January 1964 and published in the Journal of September–November 1964. Below is the remainder of the paper. Some minor rearrangement of the order and slight editing has been necessary, and sub-headings have been added. Having spent much time in the quite unprofitable but employed on the London & South Western required extremely fascinating occupation of examining the manned substations at frequent intervals, and thus possible effects of endings to historical episodes was suited only to short-range intensive exploitation. different from those that took place in fact, I have Another electric traction possibility which also been persuaded by the programme secretary to place would have had a marked effect on present-day some of those in relation to railway history before finances is the consequences one might have anti- you. Many of them raise questions that could perhaps cipated from implementation of the Weir report. Had justify further research by those with time or the the railways taken a bold line and sought to raise inclination to pursue such lines; some raise matters new capital, and observed the partisan warnings of directly connected with problems of today. For their coal-owning friends rather less, we should have example, had Gladstone’s machinery of railway had much electric traction at 1,500 volts DC and nationalisation under his 1844 Act been put into might now, 35 years later, have had a complete operation, should we have had a logically planned electric railway system far less vulnerable to road railway system that would not have needed drastic and air competition. -

Download (Pdf)

HUN T'S MERCHANTS' MAGAZINE. Established .Tuly, 1839, BY FREEMAN HUNT, EDITOR AND PROPRIETOR. · VOLUME XXIX. JULY, 1853. NUMBER I. CONTENTS OF NO. I., VOL. XXIX. ARTICLES. ART, PA.GK, I. FINANCIAL HISTORY OF THE REIGN OF LOUIS PHILIPPE.-PART n. Translated from the French of M. S. DuMciN, late Minister of Finance, for the Merchants' Magazine. 19 If. MERCANTILE BlOGRAPHY.-GEORGE HUDSON, THE "RAILROAD KING"...... 36 111. TRAITS OF TRADE-LAUDABLE AND lNlQUITOUS.-ABOUT CRBDIT-SPECULA• II'IONS . By a Merchant of Boston.... • .. • • • • . • . •. •• • . • . • . •• •• 50 IV. COMMERCIAL CITIES AND TOWNS OF THE UNITED STATES.-No. xxxrv.-THE ClTY 01.<' SA VANNAH. By Jos11:PH F. GREENOUGH, of New York, late of Georgia..... 57 V. THE BALTIMORE AND OHIO RAILROAD AND ITS WESTERN CONNECTIONS, By J.E. SNODGRAss, A. M., M. D., of Maryland........................................ 64 VI. BANK NOTE COUNTERFEITS AND ALTERATIONS.-THEIR REMEDY. By a Bank Teller ot' New York.................................................................. 72 JOURNAL OF MERCANTILE LAW, Libel for Collision, (case in U.S. District Court)............................................. T4 Letters of Credit, (case in Lord Mayor's Court, London)......... ............................ 78 Bill of Lading-Quantity-Right to pay freight on overplus when cargo is damaged, (English case).. ................................................. ....... ..•. ..•.. .• . .. •. .. 79 Act of New York r11lating to Suits against Joint Stock Companies . .. • .• 80 What is an Act of Banlcruptcy. • • . • . • . -

The Victorians: Time and Space Transcript

The Victorians: Time and Space Transcript Date: Monday, 13 September 2010 - 12:00AM Location: Museum of London The Victorians: Time and Space Professor Richard J Evans 13/9/2010 'The History of the Victorian Age', wrote Lytton Strachey in 1918, 'will never be written: we know too much about it. For', he went on, 'ignorance is the first requisite of the historian - ignorance, which simplifies and clarifies, which selects and omits, with a placid perfection unattainable by the highest art.' In modern parlance, those who wished to study the Victorians suffered from information overload. But by 'history' Strachey in fact meant narrative history, and indeed the challenge of writing a chronological account was and still is almost insurmountable, given the complexities of the age and the superabundance of evidence for them. So, Strachey concluded: It is not by the direct method of a scrupulous narration that the explorer of the past can hope to depict that singular epoch. If he is wise, he will adopt a subtler strategy. He will attack his subject in unexpected places; he will fall upon the flank, or the rear; he will shoot a sudden, revealing searchlight into obscure recesses, hitherto undivined. He will row out over that great ocean of material, and lower down into it, here and there, a little bucket, which will bring up to the light of day some characteristic specimen, from those far depths, to be examiner with a careful curiosity. This, in essence, is what I propose to do in this series of six lectures, beginning today and stretching over the next few months. -

Of Audiotape

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. CLARK TERRY NEA Jazz Master (1991) Interviewee: Clark Terry (December 14, 1920 – February 21, 2015) Interviewer: William Brower Date: June 15 and 22, 1999 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 150 pp. Transcriber’s note: Evidently there was no recording engineer available for the Clark Terry interview, and the interviewer, William Brower, handled the record process by himself. He had some technical problems. In the interview of June 15, 1999, one of the two channels is shorted out and emits nothing but a buzz, disrupting the entire session; this problem is exacerbated, affecting both channels, in the last two hours of this session. Brower acknowledges these problems at the beginning of the interview that took place one week later, on June 22, 1999. This later session has an excellent stereophonic sound. Terry: Saw a fellow sitting there, standing on a rock. He was driving around the corner, in the middle of the block. Is that close enough? Brower: Okay. We’re going to try this again. This is Bill Brower, talking with Mr. Clark Terry on June 15th for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Project, and we were getting background on the Terry family, and I’m going to ask if you would, to repeat the things that you told me about your parents’ background. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 2 Terry: My mother’s name was Mary Scott. -

The High Level Bridge a North East Icon

THE CHARTERED INSTITUTION OF HIGHWAYS & TRANSPORTATION The High Level Bridge A North East Icon A personal view by J Michael Taylor MBE The High Level Bridge is an iconic structure. Carrying both rail and road transport over the River Tyne, it is instantly recognised, by local Geordies and across the world. Opened in 1849 by Queen Victoria, it completed what is now the East Coast Main Line, between London and Edinburgh. Its design was groundbreaking, and its designer, Robert Stephenson, as well known as the bridge he created. Recently, a major refurbishment prevented the structure from becoming a museum piece and its restoration reminds us that it continues to do its job with a certain style and panache of which the profession can be proud. Michael gives his assessment on the High Level Bridge and its place in North East history. 1 Choose a favourite road or rail bridge in the north east and you will be spoilt for choice. There are many and readers will all have their favourite. Perhaps it would be the Middlesbrough Transporter Bridge, Stockton and Darlington Railway Bridge, Hounds Gill Viaduct, Kingsgate Bridge at Durham, Tyne and Wear Metro Bridge, Gateshead Millennium Bridge, Telford Bridge at Morpeth, or the Royal Border Bridge at Berwick. The list seems endless but I choose the High Level Bridge over the Tyne Gorge at Newcastle which seems to me to bring so many of the key elements of a “Highways and Transportation icon” together. By the middle of the 19th Century there had been a number of proposals to cross the Tyne at “high level” between Gateshead and Newcastle but it was the “Railway King”, George Hudson and the need to join his York, Darlington, Gateshead railway with his Newcastle to Berwick railway that caused the formation of the High Level Bridge company. -

NOTTING Hallshire. OEX 688 Martin Thomas, Elston, Newark Trent Navigation Co

• TRADES DIB.EOTOBY.] NOTTING HAllSHIRE. OEX 688 Martin Thomas, Elston, Newark Trent Navigation Co. (The), general Knight Thomas, "\Vhatton, Nottingham Mathias A. Moorgreen, Nottingham carriers by water to & from Hull, Knight Tom, Carlton-on-Trent, Newark Matthews Thomas, Ranskill, Bawtry Goole, Gainsborough, Nottingham, Monks John, 81 Colwick rd. Nottingham R.S.O. (Yorks) Deroy, Leicester, Burton & inter- )lyhill Jas. West Stockwith, Gainsboro' Meads James, Calverton, Nottingham mediate places; hell((~ office, ware- Oliver Thomas, Ivy house, Bunny,. 1\Ietcalf Fredk.l\:listerton, Gainsborough house & wharf, Island street, London Nottingham .Mettam William R. Ollerton, Newark road, Nottingham; also at Mill gate, Raynor William, West Leigh, West Hill Milner Mrs. J. Kirklinghm, Southwell Newark; & Humber Dock basin, Hull drive, l\lansfield Morley Jesse, Thoroton, Nottingham Shacklock William Henry, Farnsfield,. Morley Percy W. Edwinstowe, Newark CART OWNERS & CARTERS. Southwell Morley Samuel, Shelford, Nottingham See Carmen. Shephard Joseph, Car Colston, Nttnghm Morrell E. Cropwell Bishop, Nottingham CARTING CONTRACTORS, Turgoose Robert, Dunham, Newark Needham John, Elkesley, Retford Webster Harry, Teversal, l\Iansfield Newbert John, Laxton, Newark See Contractors. Wellsman George, Cromwell, Newark N~wton Thos. ~allam, Well?w, Newark CARVERS-WOOD Wilkinson George, Harby, Lincoln NICholson A. Bmgham, Nottingham · Wilkinson William, Harby, Lincoln North John, Woodborough, Nottingham Garrad Wm. A. 1 Stretton st.Nottinghm CATTLE REMOVER Overton Edward, Harby, Lincoln Hillebrandt W. 6 Chesterfield st.Ntnghm fBY FLOAT. Owen Jonas, East Kirkby, Nottingham l\liddlebrook Alfred, Hopkinson's yard, . ' ). Parkin George, East .Markham, Newark Upper Parliament street, Nottingham Eaton Richd. 58 Dickinson st. Nttnghm Parkin J. Normanton-on-Trent, Newark Pattison Thomas Henry, 30 Chestnut CATTLE & SHEEP Pears James Henry, Gpper Broughton, grove, West Bridgford, Nottingham MEDICINES Melton Mowbray Pheasey Edwd.