The Life of George Stephenson and of His Son Robert Stephenson; Comprising Also a History of the Invention and Introduction of T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Book Coastal Walks Around Anglesey

COASTAL WALKS AROUND ANGLESEY : TWENTY TWO CIRCULAR WALKS EXPLORING THE ISLE OF ANGLESEY AONB PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Carl Rogers | 128 pages | 01 Aug 2008 | Mara Books | 9781902512204 | English | Warrington, United Kingdom Coastal Walks Around Anglesey : Twenty Two Circular Walks Exploring the Isle of Anglesey AONB PDF Book Small, quiet certified site max 5 caravans or Motorhomes and 10 tents set in the owners 5 acres smallholiding. Search Are you on the phone to our call centre? Discover beautiful views of the Menai Strait across the castle and begin your walk up to Penmon Point. Anglesey is a popular region for holiday homes thanks to its breath-taking scenery and beautiful coast. The Path then heads slightly inland and through woodland. Buy it now. This looks like a land from fairy tales. Path Directions Section 3. Click here to receive exclusive offers, including free show tickets, and useful tips on how to make the most of your holiday home! The site is situated in a peaceful location on the East Coast of Anglesey. This gentle and scenic walk will take you through an enchanting wooded land of pretty blooms and wildlife. You also have the option to opt-out of these cookies. A warm and friendly welcome awaits you at Pen y Bont which is a small, family run touring and camping site which has been run by the same family for over 50 years. Post date Most Popular. Follow in the footsteps of King Edward I and embark on your walk like a true member of the royal family at Beaumaris Castle. -

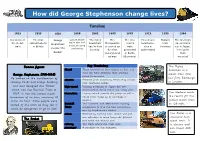

How Did George Stephenson Change Lives?

How did George Stephenson change lives? Timeline 1812 1825 1829 1850 1863 1863 1879 1912 1938 1964 Invention of The first George Luxury steam ‘The flying The The first First diesel Mallard The first high trains with soft the steam railroad opens Stephenson Scotsman’ Metropolitan electric locomotive train speed trains train in Britain seats, sleeping had its first is opened as train runs in invented run in Japan. invents ‘The and dining journey. the first presented Switzerland ‘The bullet Rocket’ underground in Berlin train railway (Germany) invented’ Key Vocabulary Famous figures The Flying diesel These locomotives burn diesel as fuel and Scotsman is a were far more powerful than previous George Stephenson (1781-1848) steam train that steam locomotives. He worked on the development of ran from Edinburgh electric Powered from electricity which they collect to London. railway tracks and bridge building from overhead cables. and also designed the ‘Rocket’ high-speed Initially produced in Japan but now which won the Rainhill Trials in international, these trains are really fast. The Mallard holds 1829. It was the fastest steam locomotive Engines which provide the power to pull a the record for the locomotive of its time, reaching 30 whole train made up of carriages or fastest steam train miles an hour. Some people were wagons. Rainhill The Liverpool and Manchester railway at 126 mph. scared of the train as they felt it Trials competition to find the best locomotive, could be dangerous to go so fast! won by Stephenson’s Rocket. steam Powered by burning coal. Steam was fed The Bullet is a into cylinders to move long rods (pistons) Japanese high The Rocket and make the wheels turn. -

Publications Robert Stephenson – Engineer & Scientist

The Robert Stephenson Trust – Publications Robert Stephenson – Engineer & Scientist – The Making of a Prodigy by Victoria Haworth 185 x 285 90pp ISBN 0 9535 1621 0 Softback £9.95 postage & packing £1.50 The work of Robert Stephenson has always been overshadowed by that of his father George and the author attempts to lay to rest the confusion that various myths have created. The book highlights Robert’s formative years and his major contribution to the development of the steam locomotive design, including notable locomotives such as Rocket, Planet and Patentee . The factory in Newcastle, which bears his name, not only produced these machines but trained talents in abundance, changing the face of civilisation. Also included is a chronology of the main events in his life. Robert Stephenson: Railway Engineer by John Addyman & Victoria Haworth A4 195pp ISBN 1 873513 60 7 Hardback £19.95 postage & packing £5.00 This biography seeks to return Robert Stephenson to his rightful position as the pre-eminent engineer of the Railway Age. The book surveys the whole range of his railway work and aims to correct the imbalance due to Smiles who credited most of Robert’s early work to his father George. All aspects of his work are covered, from very important locomotive development to railway building and consultancy around the world. Fully referenced primary sources and well reproduced lithographs, drawings and other art work complement this essential reference book. The High Level Bridge and Newcastle Central Station by John Addyman and Bill Fawcett A4 152pp ISBN 1 873513 28 3 Softback £9.95 postage & packing £3.00 This book recognises the 150 th anniversaries of the opening of the High Level Bridge and the Central Station. -

LIVES of the ENGINEERS. the LOCOMOTIVE

LIVES of the ENGINEERS. THE LOCOMOTIVE. GEORGE AND ROBERT STEPHENSON. BY SAMUEL SMILES, INTRODUCTION. Since the appearance of this book in its original form, some seventeen years since, the construction of Railways has continued to make extraordinary progress. Although Great Britain, first in the field, had then, after about twenty-five years‘ work, expended nearly 300 millions sterling in the construction of 8300 miles of railway, it has, during the last seventeen years, expended about 288 millions more in constructing 7780 additional miles. But the construction of railways has proceeded with equal rapidity on the Continent. France, Germany, Spain, Sweden, Belgium, Switzerland, Holland, have largely added to their railway mileage. Austria is actively engaged in carrying new lines across the plains of Hungary, which Turkey is preparing to meet by lines carried up the valley of the Lower Danube. Russia is also occupied with extensive schemes for connecting Petersburg and Moscow with her ports in the Black Sea on the one hand, and with the frontier towns of her Asiatic empire on the other. Italy is employing her new-born liberty in vigorously extending railways throughout her dominions. A direct line of communication has already been opened between France and Italy, through the Mont Cenis Tunnel; while p. ivanother has been opened between Germany and Italy through the Brenner Pass,—so that the entire journey may now be made by two different railway routes excepting only the short sea-passage across the English Channel from London to Brindisi, situated in the south-eastern extremity of the Italian peninsula. During the last sixteen years, nearly the whole of the Indian railways have been made. -

Boiler Feed Water Treatment

Boiler Feed Water Treatment: A case Study Of Dr. Mohamod Shareef Thermal Power Station, Khartoum State, Sudan Motawakel Sayed Osman Mohammed Ahmed B.Sc. (Honours) in Textile Engineering Technology University of Gezira (2006) A Dissertation Submitted to the University of Gezira in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Award of the Degree of Master of Science In Chemical Engineering Department of Applied Chemistry and Chemical Technology Faculty of Engineering and Technology University of Gezira January,2014 I Boiler Feed Water Treatment: A case Study Of Dr. Mohamod Shareef Thermal Power Station, Khartoum State, Sudan Motawakel Sayed Osman Mohammed Ahmed Supervision Committee: Name Position Signature Dr. Bshir Mohammed Elhassen Main Supervisor …………………. Dr. Mohammed Osman Babiker Co-supervisor ………………….. Date : January , 2014 II Boiler Feed Water Treatment: A case Study Of Dr. Mohamod Shareef Thermal Power Station, Khartoum State, Sudan Motawakel Sayed Osman Mohammed Ahmed Examination Committee: Name Position Signature Dr. Bshir Mohammed Elhassen Chair Person ……………… Dr.Bahaaeldeen Siddig Mohammed External Examiner ………………… Dr. Mustafa Ohag Mohammed Internal Examiner ………………… Date of Examination : 6. January.2014 III Dedication This research is affectionately dedicated to the souls of my parents , To my family With gratitude and love To whom ever love knowledge I Acknowledgment I would like to thank Dr. Basher Mohammed Elhassan the main Supervisor for his guidance and help. my thank also extended to Dr. Mohammed Osman Babiker my Co-supervisor for his great help. my thanks also extended to Chemical Engineers in Dr. Mohamod Sharef Thermal Power Station. II Boiler Feed Water Treatment: A case Study Of Dr. Mohamod Sharef Thermal Power Station, Khartoum State, Sudan Motawakel Sayed Osman Mohammed Ahmed Abstract A boiler is an enclosed vessel that provides a means for combustion heat to be transferred to water until it becomes heated water or steam. -

Lesson Plan Created by Tina Corri on Behalf of Sunderland Culture

Lesson plan created by Tina Corri on behalf of Sunderland Culture STEAM Teachers Notes and Lesson Plans for KS2/KS3 Teachers STEAM Teachers Notes and Lesson Plans for KS2/KS3 Teachers Welcome to Sunderland Culture’s Cultural Toolkit for STEAM activities! This resource contains notes and lesson plans linking to STEAM education. They are created for KS2 and KS3 teachers, and are editable. They are designed to be easy to use, adaptable and creative - ready to plug in and play. The activities have been developed in partnership with teachers, and take Sunderland’s people and places as their inspiration. Teacher Notes - Introduction to STEAM What is STEAM? STEAM stands for Science, TechnologyWelcome, Engineering to Sunderland, Art and Maths. By placing art at theCulture’s heart of STEM Cultural Toolkit education, it recognises the vitalfor role STEAM of the arts activities!and This resource contains notes and lesson plans linking creativity in scientific discoveries,to STEAM inno education.vative design, They are createdand for KS2 and KS3 ground-breaking engineering. teachers, and are editable. They are designed to be easy to use, adaptable and creative - ready to plug in and play. The activities STEAM education explores whahavet happens been developed when in ypartnershipou combine with teachers,these different subjects together and take Sunderland’s people and places as their as a way to explore real-world situainspiration.tions and challenges. It is an approach which encourages invention and curiosity throughTeacher creative, Noteshands-on - Introductionand experimen tot STEAMal learning. At the core of STEAM education are two key concepts: What is STEAM? STEAM stands for Science, Technology, Engineering, Art and Maths. -

Passenger Rail (Edited from Wikipedia)

Passenger Rail (Edited from Wikipedia) SUMMARY A passenger train travels between stations where passengers may embark and disembark. The oversight of the train is the duty of a guard/train manager/conductor. Passenger trains are part of public transport and often make up the stem of the service, with buses feeding to stations. Passenger trains provide long-distance intercity travel, daily commuter trips, or local urban transit services. They even include a diversity of vehicles, operating speeds, right-of-way requirements, and service frequency. Passenger trains usually can be divided into two operations: intercity railway and intracity transit. Whereas as intercity railway involve higher speeds, longer routes, and lower frequency (usually scheduled), intracity transit involves lower speeds, shorter routes, and higher frequency (especially during peak hours). Intercity trains are long-haul trains that operate with few stops between cities. Trains typically have amenities such as a dining car. Some lines also provide over-night services with sleeping cars. Some long-haul trains have been given a specific name. Regional trains are medium distance trains that connect cities with outlying, surrounding areas, or provide a regional service, making more stops and having lower speeds. Commuter trains serve suburbs of urban areas, providing a daily commuting service. Airport rail links provide quick access from city centers to airports. High-speed rail are special inter-city trains that operate at much higher speeds than conventional railways, the limit being regarded at 120 to 200 mph. High-speed trains are used mostly for long-haul service and most systems are in Western Europe and East Asia. -

This Excerpt from the First Part of the Last Journey of William Huskisson Describes the Build-Up to the Official Opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

Downloaded from simongarfield.com © Simon Garfield 2005 This excerpt from the first part of The Last Journey of William Huskisson describes the build-up to the official opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. Huskisson’s fatal accident was about two hours away. The sky was brightening. For John Moss and the other directors assembled at the company offices in Crown Street it was already a day of triumph, whatever the ensuing hours might bring. They had received word that the Duke of Wellington, the Prime Minister, had arrived in Liverpool safely, and was on his way, though there appeared to be some delay. As they waited, they were encouraged by the huge crowds and the morning’s papers. Liverpool enjoyed a prosperous newspaper trade, and in one week a resident might decide between the Courier, the Mercury, the Journal, the Albion and the Liverpool Times, and while there was little to divide them on subject matter, they each twisted a Whiggish or Tory knife. Advertisements and paid announcements anchored the front pages. Mr Gray, of the Royal College of Surgeons, announced his annual trip from London to Liverpool to fit clients with false teeth, which were fixed “by capillary attraction and the pressure of the atmosphere, thereby avoiding pinning to stumps, tieing, twisting wires...” Courses improving handwriting were popular, as were new treatments for bile, nervous debility and slow fevers. The Siamese twins at the King’s Arms Hotel were proving such a draw that they were remaining in Liverpool until Saturday 25th, when, according to their promoter Captain Coffin, “they must positively leave”. -

U DX251 Account Books of John Hudson of Howsham 1799

Hull History Centre: Account books of John Hudson of Howsham U DX251 Account books of John Hudson of Howsham 1799 Biographical Background: John Hudson of Howsham, a Scarborough merchant and farmer, was probably born in 1756 and died in 1808. He married an Elizabeth Ruston and had seven children, including two daughters and five sons. His youngest son, George Hudson, later became known as 'The Railway King'. George Hudson was born in March 1800 and died on 14 December 1871. He became famous as a English railway financier, earning the nickname "The Railway King”. He initially apprenticed as a draper at Bell and Nicholson in York. In 1820 he was taken on by the firm as a tradesman and given a share of the business. By 1827 it was the largest business in York. Also in 1827, he inherited £30,000 from his great uncle. Hudson played a major part in establishing the York Union Banking Company and he first became Lord Mayor in York in 1837. He was Lord Mayor three times as well as deputy-lieutenant for Durham and Conservative Member of Parliament for Sunderland from August 1845 until 1859. Hudson was instrumental in the expansion of the railways across England and in the Railway Clearing House (1842). He amalgamated the North Midland, the Midland Counties Railway and the Birmingham & Derby Junction Railway in 1844 to become the Midland Railway. He initiated the Newcastle and Darlington line in 1841 and with George Stephenson, planned and carried out the extension of the York & North Midland Railway to Newcastle. By 1844 he had control of over a thousand miles of railway. -

NATURE 19 the Map Was Drawn, and So the Omission of the Name of Tion Set In, Due to Errors Introduced by Repeated Copying, St

NATURE 19 the map was drawn, and so the omission of the name of tion set in, due to errors introduced by repeated copying, St. Gilles can be accounted for. Vesconte knew that uncontrolled by any check. there was no longer a port of St. Gilles, if he knew that From the evidence outlined above we may reconstruct there ever had been, and, being of no interest to those the history of St. Gilles as a seaport. In Roman times for whom the map was made, it was omitted, but the it was an inland town, of no great importance, past topography he took, directly or indirectly, from the which one of the branches of the Rhone flowed, as at older map. If this map is compared with a restoration the present day, but, instead of turning southwards, of the twelfth century topography, as deduced from the river flowed on to the west, in a valley cut out of the modern maps of the region, upraised alluvium, to where the etang de Mauguio now the agreement, as regards stands. Then came the subsidence in the Dark Ages, the eastern end of the inlet, the lower part of this valley became submerged, and an is so close, that his repre inlet of the sea was formed, with sufficient depth of sentation of the western por water to enable ships to reach St. Gilles, which, by 108o, tion, where direct restoration had become so well established that it was selected Fw. 3·-Coast between Cette is more uncertain, may be as the most appropriatelanding-place for a princess of and Cap Couronne, from the map by Petrus Vesconte, dated taken as corroboration of the Sicily, on her way to the Court of France. -

The Design of Modern Steel Bridges

The Design of Modern Steel Bridges Second Edition Sukhen Chatterjee BE, MSc, DIC, PhD, FICE, MIStructE The Design of Modern Steel Bridges The Design of Modern Steel Bridges Second Edition Sukhen Chatterjee BE, MSc, DIC, PhD, FICE, MIStructE # Sukhen Chatterjee, 1991, 2003 First edition published 1991 This edition first published 2003 by Blackwell Science Ltd, a Blackwell Blackwell Science Ltd Publishing Company Editorial Offices: Library of Congress Osney Mead, Oxford OX2 0EL, UK Cataloging-in-Publication Data Tel: +44 (0)1865 206206 is available Blackwell Publishing, Inc., 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5018, USA ISBN 0-632-05511-1 Tel: +1 781 388 8250 Iowa State Press, a Blackwell Publishing A catalogue record for this title is available Company, 2121 State Avenue, Ames, Iowa from the British Library 50014-8300, USA Tel: +1 515 292 0140 Set in Times and produced by Gray Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd, Publishing, Tunbridge Wells, Kent 550 Swanston Street, Carlton South, Printed and bound in Great Britain by Victoria 3053, Australia MPG Books Ltd, Bodmin, Cornwall Tel: +61 (0)3 9347 0300 Blackwell Wissenschafts Verlag, For further information on Kurfu¨rstendamm 57, 10707 Berlin, Blackwell Science, visit our website: Germany www.blackwell-science.co.uk Tel: +49 (0)30 32 79 060 The right of the Author to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. -

Menai Strait Spectacular Llanfair PG to Menai Bridge on the Isle of Anglesey

Menai Strait Spectacular Llanfair PG to Menai Bridge on the Isle of Anglesey A walk of unfolding delights; not just the world famous Menai Suspension Bridge built by Telford in 1826 and the Britannia Bridge built by Stephenson in 1850, but also a mighty statue of Lord Nelson, tidal lagoons, a Church on a tiny island surrounded by the racing tides and beautiful views up and down the ever-changing Menai Strait that separates the Isle of Anglesey from mainland Britain. A walk you'll remember forever. " Distance 11.02 miles / 17.7 km Duration 4-5 hours Difficulty Easy Starting from Marquis of Anglesey's column Car Park Menai Strait Spectacular www.walkingnorthwales.co.uk !1 / !4 www.walkingnorthwales.co.uk Trail Map ! ! !Key ! ! ! ! Car Park Tourist Attraction Castle/Stately Lighthouse/Tower ! Harbour/" Walks/Trails Berth/" Flora Café/Restaurant Mooring ! Sculpture/" Place of" Bridge/River Accommodation Monument Worship Crossing Public! House/Bar ! ! ! Menai Strait Spectacular www.walkingnorthwales.co.uk !2 / !4 Chapters ! Chapter 1 Arrival and the Marquess of Anglesey Column The walk begins at parking lot below the Marquis of Anglesey's column. The first thing to do is follow the trail through the small woodland to the Column, which is well worth a visit, and is described in features. The view from the top gives a wonderful panorama across the Menai Strait to the rugged hills and mountains of Snowdonia. It also shows you the walk you're about to enjoy, exploring the shoreline of the Strait. Once !back down exit the parking lot onto to the main road and turn right.