Middle and Late Phrygian Gordion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monuments, Materiality, and Meaning in the Classical Archaeology of Anatolia

MONUMENTS, MATERIALITY, AND MEANING IN THE CLASSICAL ARCHAEOLOGY OF ANATOLIA by Daniel David Shoup A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Art and Archaeology) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Professor Elaine K. Gazda, Co-Chair Professor John F. Cherry, Co-Chair, Brown University Professor Fatma Müge Göçek Professor Christopher John Ratté Professor Norman Yoffee Acknowledgments Athena may have sprung from Zeus’ brow alone, but dissertations never have a solitary birth: especially this one, which is largely made up of the voices of others. I have been fortunate to have the support of many friends, colleagues, and mentors, whose ideas and suggestions have fundamentally shaped this work. I would also like to thank the dozens of people who agreed to be interviewed, whose ideas and voices animate this text and the sites where they work. I offer this dissertation in hope that it contributes, in some small way, to a bright future for archaeology in Turkey. My committee members have been unstinting in their support of what has proved to be an unconventional project. John Cherry’s able teaching and broad perspective on archaeology formed the matrix in which the ideas for this dissertation grew; Elaine Gazda’s support, guidance, and advocacy of the project was indispensible to its completion. Norman Yoffee provided ideas and support from the first draft of a very different prospectus – including very necessary encouragement to go out on a limb. Chris Ratté has been a generous host at the site of Aphrodisias and helpful commentator during the writing process. -

119Th Annual Meeting Archaeology at Work

Archaeological Institute of America 119TH ANNUAL MEETING PROGRAMARCHAEOLOGY AT WORK BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS JANUARY 4–7, 2018 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS JANUARY 4–7, 2018 Welcome to Boston! Welcome to the 119th Joint Annual Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America and the Society for Classical Studies. This year, we are in Boston, Massachusetts, the headquarters city for the AIA. Our sessions will take place at the Boston Marriott Copley Place, in close proximity to the Boston Public Library and the finish line for the famous Boston Marathon. Both the Marriott and the overflow hotel, the Westin Copley Place, are near public transportation, namely, the Copley T train station. Using the T will give you ready access to Boston’s museums and many other cultural offerings. Table of Contents In addition to colloquia on topics ranging from gender and material culture to landscapes, monuments, and memories, General Information .........2 the academic program includes workshops and sessions on Program-at-a-Glance .....4-6 digital technology and preservation, philanthropy and funding, and conservation. I thank Ellen Perry, Chair, and the members of the Program for the Annual Meeting Committee for putting Exhibitors .................. 12-13 together such an excellent program. Thanks also to the Staff at the Boston office for their efforts in making this meeting a success. Thursday, January 4 Day-at-a-Glance ..........14 The Opening Night Lecture will be delivered by Professor John Papadopoulos of UCLA’s Department of Classics and the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology. Professor Papadopoulos has Friday, January 5 published 12 books, including Athenian Agora Volume XXXVI on the Iron Age cemeteries. -

AR 88 1968-69.Pdf

{-·--·-. -·--·"'-.._ ............. ·--·-·- ............... ..... ........ ........ ._ .._ .._ ........ ...... ·-·---·-·--·-- ............... -. .._ . .__ ......... ._ .._ ........ ........ ----·-- ·-.._ . ._ ........ ........ -. ....... ·-·-·- ·; ( i I ~ ...................... ._.............. ......................................................... ._................................... ....... ..................... ....................................................................... , ................................................................ ~ ) i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i ? i i i I i i i i i i i i i i i i l t AMERICAN SCHOOL OF t ~ i i i i l } CLASSICAL STUDIES l ~ i i i i i i i i t i AT ATHENS l ~ i I i i i I i i • ? I i .'-1· I I ' i i . I i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i ? ? i I i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i 1 i I i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i EIGHTY-EIGHTH ANNUAL REPORT i i 1 i 196 ~-1969 i i i i i i i i i i I i i . .... ·- - -----~·- -·-·-- -- -· ... - ~ - - .............. ._. ....... -.-............... ._ ................ ---· ---· ---·-· .............. -. ........- ---·-................ -----------·-·-·--·-·-·-1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE ARTICLES OF INCORPORATION 4 BOARD OF TRUSTEES 5 MANAGING CoMMITTEE 7 CoMMITTEES OF THE MANAGING CoMMITTEE 14 STAFF oF THE ScHOOL 15 CouNCIL OF THE ALUMNI AssociATION • .. 17 THE AuxiLIARY FuND AssociATION 17 CooPERATING INSTITUTIONs • 18 REPORTS: Director 20 Librarian of the School 29 Librarian of the Gennadeion . 33 Professors of Archaeology 37 Field Director of the Agora Excavations 41 Field Director of the Corinth Excavations 46 Special Research Fellows: Visiting Professors SO Secretary of the School 53 Chairman of the Committee on Admissions and Fellowships 54 Chairman of the Committee on Publications 56 Director of the Summer Session II 64 Treasurer of the Auxiliary Fund 67 Report of the Treasurer . -

Keith R. Devries Papers 1153 Finding Aid Prepared by James Dewalt and Dan Cavanaugh

Keith R. DeVries papers 1153 Finding aid prepared by James DeWalt and Dan Cavanaugh. Last updated on March 02, 2017. University of Pennsylvania, Penn Museum Archives 2013 Keith R. DeVries papers Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 6 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 6 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 8 Correspondence........................................................................................................................................8 Publications and Presentations............................................................................................................. -

Volume 44, Fall 2007

ARIT Newsletter American Research Institute in Turkey Number 44, Fall 2007 President LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT G. Kenneth Sams Immediate Past President I am very pleased to announce that ARIT has made a successful application for Machteld J. Mellink a Challenge Grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, for support Vice President of our libraries in Istanbul and Ankara. The NEH will provide $1 for every $3 that Ahmet Karamustafa Secretary ARIT is able to raise for the purpose, for a total minimum amount (what we raise Linda Darling plus the NEH match) of $2.2 million. ARIT has five years within which to complete Treasurer the Challenge Grant. Thanks to generous sums that came to ARIT during the past Maria deJ. Ellis year, we are already off to a good start in meeting the match. Although the great Directors Cornell Fleischer bulk of what we raise will go into much-needed and long-desired endowment, we Beatrice Manz will also have the wherewithal to proceed with a move to larger quarters for space- Scott Redford impaired ARIT-Istanbul. ARIT will soon launch a major fundraising campaign, one Brian Rose Alice-Mary Talbot that we hope will put into place a permanent mechanism for on-going fundraising Honorary Director efforts. We will very much appreciate your generosity. Lee Striker Beginning in 2001, the Joukowsky Family Foundation has generously provided Institutional Members funding for ARIT to offer John Freely Fellowships, named in honor of the physicist Full Members University of Chicago and author who is perhaps best known in broad circles for his masterful Strolling Dumbarton Oaks through Istanbul. -

Volume 45, Spring 2008

ARIT Newsletter American Research Institute in Turkey Number 45, Spring 2008 President LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT G. Kenneth Sams As I announced in the last Newsletter, ARIT has been most fortunate to receive Immediate Past President Machteld J. Mellink from the National Endowment for the Humanities a Challenge Grant with a full Vice President potential (1:3 matching) of 2.2 million dollars. The purpose of the grant is to endow Ahmet Karamustafa and enhance the ARIT libraries in Istanbul and Ankara. Thanks to the timely receipt Secretary Linda Darling of a generous anonymous gift and a generous bequest from the estate of Machteld Treasurer Mellink, ARIT has made a good start toward meeting the match. Yet we still have Maria deJ. Ellis a considerable amount of money to raise. A finance and fundraising committee Directors Cornell Fleischer will guide us along the way. We need to identify potential major donors who will Beatrice Manz constitute the leadership force of the campaign. We are hopeful that in the end, Scott Redford Brian Rose with a successful NEH campaign behind us, we will have set in place a permanent Jennifer Tobin fundraising mechanism to ensure ARIT’s continued well being. Honorary Director Lee Striker Since 1997, ARIT has been privileged to award Samuel H. Kress Foundation Institutional Members Pre-doctoral Fellowships in Archaeology and the History of Art. Through the cur- Full Members rent year, a total of 29 young scholars have conducted research in Turkey as Kress University of Chicago Dumbarton Oaks Fellows. One of them was ARIT-Ankara Director Bahadır Yıldırım, who studied a Georgetown University series of Roman-period sculptural reliefs from Aphrodisias. -

ARIT Newsletter American Research Institute in Turkey

ARIT Newsletter American Research Institute in Turkey Number 44, Fall 2007 President LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT G. Kenneth Sams Immediate Past President I am very pleased to announce that ARIT has made a successful application for Machteld J. Mellink a Challenge Grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, for support Vice President of our libraries in Istanbul and Ankara. The NEH will provide $1 for every $3 that Ahmet Karamustafa Secretary ARIT is able to raise for the purpose, for a total minimum amount (what we raise Linda Darling plus the NEH match) of $2.2 million. ARIT has five years within which to complete Treasurer the Challenge Grant. Thanks to generous sums that came to ARIT during the past Maria deJ. Ellis year, we are already off to a good start in meeting the match. Although the great Directors Cornell Fleischer bulk of what we raise will go into much-needed and long-desired endowment, we Beatrice Manz will also have the wherewithal to proceed with a move to larger quarters for space- Scott Redford impaired ARIT-Istanbul. ARIT will soon launch a major fundraising campaign, one Brian Rose Alice-Mary Talbot that we hope will put into place a permanent mechanism for on-going fundraising Honorary Director efforts. We will very much appreciate your generosity. Lee Striker Beginning in 2001, the Joukowsky Family Foundation has generously provided Institutional Members funding for ARIT to offer John Freely Fellowships, named in honor of the physicist Full Members University of Chicago and author who is perhaps best known in broad circles for his masterful Strolling Dumbarton Oaks through Istanbul. -

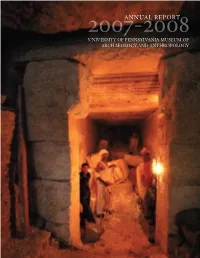

Annual Report

2007ANN-U2008AL REPORT UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA MUSEUM OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND ANTHROPOLOGY ar | UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA MUSEUM OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND ANTHROPOLOGY | ar 2007ANN-U2008AL REPORT UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA MUSEUM OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND ANTHROPOLOGY 3 Letter from the Chair of the Board of Overseers 4 Letter from the Williams Director 5 THE YEAR IN REVIEW Collections and Programs 6 Collections Showcase: New Exhibitions and Traveling Exhibits 11 A Living Museum: Special Programs, Events, and Public Lectures 16 Preserving Our Collections: Conservation Work and Digitizing Our Archives 17 Stewarding Our Collections: The Museum’s Repatriation Office and Committee 18 Sharing Our Collections: Outgoing Loans from the Penn Museum Outreach and Collaboration 20 Community Outreach: Educational Programs and Collaborations 26 Global Engagement: Protecting the World’s Cultural Heritage Research and Dissemination 28 Generating Knowledge: Research Projects around the World 41 Disseminating Knowledge: Penn Museum Publications 42 Preserving and Sharing Knowledge: Digitizing Collections and Archives 44 Financial Highlights 45 IN GrateFUL ACKNOWLEDGMent 46 Highlights 50 Perpetual Support 51 Support of the Physical Plant 52 Annual Sustaining Support 62 Support of Museum Research Projects 64 Board of Overseers ON THE COVER The blocked tomb of Senwosret III at Abydos. Photo by Josef Wegner University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology 3260 South Street Philadelphia, PA 19104-6324 © 2008 University of Pennsylvania All rights reserved. | ar letter from the chair of the board of overseers The 2007/2008 academic year was a remarkable one in which as the holder of an extraordinary collection of artifacts and the University of Pennsylvania publicly launched its largest archival materials from a remarkable series of archaeological ever campaign—Making History—in October 2007 and saw excavations, including those of many World Heritage Sites, that campaign soar beyond the $2 billion mark by the end and anthropological expeditions. -

{Replace with the Title of Your Dissertation}

A Cosmopolitan Village: The Hellenistic Settlement at Gordion A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Martin Gregory Wells IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Andrea M. Berlin, Advisor May, 2012 © Martin Gregory Wells 2012 Acknowledgements This study is dedicated to my parents, John and Judy. Their constant love, enthusiasm, and support throughout my undergraduate and graduate careers have made this all possible. I thank them with all my heart for what they have done for me and I hope I continue to make them proud. And thank you to the rest of my family, Matt and Julia, Phil and Carla, Charlie and Donna, Cathleen Getty, and the entire Wells and Martois families. There will be more to talk about now that this is finished. I am deeply indebted to the members of my dissertation committee: Andrea Berlin of Boston University, G. Kenneth Sams of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Barbara Tsakirgis of Vanderbilt University, and Philip Sellew and Nita Krevans, both of the University of Minnesota. Despite their busy teaching, research, traveling and personal schedules, they found time to read my drafts and offer helpful comments and criticism. I thank them for all their assistance in bringing this dissertation to completion. I began this project in 2003 and, since that time, the faculty of the Department of Classical and Near Eastern Studies at the University of Minnesota has been unfailing in their financial support. I am especially grateful for their nomination of my work for the Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship in addition to numerous grants for research trips to Gordion and to the Gordion Archives at the University of Pennsylvania Museum. -

The Archaeology of Phrygian Gordion, Royal City of Midas Ellen L

The Archaeology of Phrygian Gordion, Royal City of Midas Ellen L. Kohler at Gordion. Source: Gordion Archive, Penn Museum, image 175958. gordion special studies I: The Nonverbal Graffiti, Dipinti, and Stamps by Lynn E. Roller, 1987 II: The Terracotta Figurines and Related Vessels by Irene Bald Romano, 1995 III: Gordion Seals and Sealings: Individuals and Society by Elspeth R. M. Dusinberre, 2005 IV: The Incised Drawings from Early Phrygian Gordion by Lynn E. Roller, 2009 V: Botanical Aspects of Environment and Economy at Gordion, Turkey by Naomi F. Miller, 2010 VI: The New Chronology of Iron Age Gordion edited by C. Brian Rose and Gareth Darbyshire, 2011 gordion excavations final reports I: Three Great Early Tumuli by Rodney S. Young, 1982 II: The Lesser Phrygian Tumuli. Part 1: The Inhumations by Ellen L. Kohler, 1995 III: The Bronze Age by Ann Gunter, 1991 IV: The Early Phrygian Pottery by G. Kenneth Sams, 1994 museum monograph 136 GORDION SPECIAL STUDIES VII The Archaeology of Phrygian Gordion, Royal City of Midas C. Brian Rose, editor university of pennsylvania museum of archaeology and anthropology philadelphia Financial support for this volume’s publication was provided by the Penn Museum, the 1984 Foundation, the Provost’s Research Fund of the University of Pennsylvania, and the George B. Storer Foundation. ESNDPAPER : Map of the Near East and the eastern Mediterranean featuring sites mentioned in this volume. Drawing: Kimberly Leaman. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The archaeology of Phrygian Gordion, royal city of Midas / edited by C. Brian Rose. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Mary Hamilton Swindler 1884-1967 By

Mary Hamilton Swindler 1884-1967 by As an interpretive archaeologist who remained always closely in touch with her background as a student of Classical literature, Mary Hamilton Swindler contributed to Twentieth Century archaeology through her publications and sponsorships. Her two major achievements were a comprehensive book on Ancient Painting, widely acclaimed for its scholarship, and an innovative fourteen year editorship of the American Journal of Archaeology. Among the many honors and awards given in recognition of her accomplishments were several of which she was the first woman recipient. From 1912 through 1949, she was a professor of archaeology and Classics at Bryn Mawr College, the first of the succession of distinguished women archaeologists who have created professional reputations in virtual identification with the college. The large number of significant Bryn Mawr archaeologists who attribute the beginnings of their careers to Professor Swindler’s inspirational teaching and their continuation to her practical support and guidance also comprise a major contribution to the history of archaeology in America. Personal Background Proud of her origins in the “open spaces of the Middle West,” Mary Hamilton Swindler regarded her early environment as a shaping factor in her life. “It taught me 1 what kindness and tolerance I have, as well as the ability to live and work with people.” Her “open spaces signified the university town of Bloomington Indiana where she was born on New Year’s Day 1884, as the second daughter of Harrison T. Swindler, baker and restaurant proprietor, and his wife Ida M. Hamilton; and where she received her education from elementary school through the M.A. -

Troy and the Trojan War: a Symposium Held at Bryn Mawr College, October 1984

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Bryn Mawr College Publications, Special Books, pamphlets, catalogues, and scrapbooks Collections, Digitized Books 1986 Troy and the Trojan War: A Symposium Held at Bryn Mawr College, October 1984 Machteld J. Mellink Bryn Mawr College Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.brynmawr.edu/bmc_books Part of the Liberal Studies Commons, and the Women's History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Custom Citation Mellink, Machteld J., ed., Troy and the Trojan War: A Symposium Held at Bryn Mawr College, October 1984 (Bryn Mawr, 1986). This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. https://repository.brynmawr.edu/bmc_books/1 For more information, please contact [email protected]. TROY AND THE TROJAN WAR A SYMPOSIUM HELD AT BRYN MAWR COLLEGE OCTOBER 1984 TROY AND THE TROJAN WAR A SYMPOSIUM HELD AT BRYN MAWR COLLEGE OCTOBER 1984 Papers by J. LAWRENCE ANGEL, HANS G. GOTERBOCK, MANFRED KORFMANN, JEROME SPERLING, EMILY D.T. VERMEULE AND CALVERT WATKINS Edited by MACHTELD J. MELLINK BRYN MAWR COLLEGE BRYN MAWR, PA. 1986 Copyright © 1986, 1999 by Bryn Mawr Commentaries Manufactured in the United States of America ISBN 0-929524-59-4 Printed and distributed by Bryn Mawr Commentaries Thomas Library Bryn Mawr College 101 North Merion Avenue Bryn Mawr, PA 19010-2899 Outside cover: The first published illustration of the Tabula Iliaca, taken from Bernard de Montfaucon, L' anti quite expliquee et representee en figures IV (Paris 1719) PREFACE On October 19, 1984 the Departments of Greek, Latin and Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology of Bryn Mawr College held a symposium on the Trojan War as part of the cele~rations of the Centennial of Bryn Mawr College, 1885-1985.