Our Consumer Place Newlsetter May 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Hunger Strike to Challenge International Domination by Biopsychiatry

A Hunger Strike to Challenge International Domination by Biopsychiatry This fast is about human rights in mental health. The psychiatric pharmaceutical complex is heedless of its oath to "first do no harm." Psychiatrists are able with impunity to: *** Incarcerate citizens who have committed crimes against neither persons nor property. *** Impose diagnostic labels on people that stigmatize and defame them. *** Induce proven neurological damage by force and coercion with powerful psychotropic drugs. *** Stimulate violence and suicide with drugs promoted as able to control these activities. *** Destroy brain cells and memories with an increasing use of electroshock (also known as electro-convulsive therapy) *** Employ restraint and solitary confinement - which frequently cause severe emotional trauma, humiliation, physical harm, and even death - in preference to patience and understanding. *** Humiliate individuals already damaged by traumatizing assaults to their self-esteem. These human rights violations and crimes against human decency must end. While the history of psychiatry offers little hope that change will arrive quickly, initial steps can and must be taken. At the very least, the public has the right to know IMMEDIATELY the evidence upon which psychiatry bases its spurious claims and treatments, and upon which it has gained and betrayed the trust and confidence of the courts, the media, and the public. WHY WE FAST There are many different ways to help people experiencing severe mental and emotional crises. People labeled with a psychiatric disability deserve to be able to choose from a wide variety of these empowering alternatives. Self-determination is important to achieve real recovery. However, choice in the mental health field is severely limited. -

Journal of Critical Psychology, Counselling and Psychotherapy Appropriate, and Have to Use Force, Which Constitutes a Threat

Winter 2010 Peter Lehmann 209 Medicalization and Peter * Lehmann Irresponsibility Through the example of an adolescent harmed by a variety of psychiatric procedures this paper concludes that bioethical and legal action (involving public discussion of human rights violations) should be taken to prevent further uninhibited unethical medicalization of problems that are largely of a social nature. Each human being loses, if even one single person allows himself to be lowered for a purpose. (Theodor Gottlieb von Hippel the Elder, 1741–1796, German enlightener) Beside imbalance and use of power, medicalization – the social definition of human problems as medical problems – is the basic flaw at the heart of the psychiatric discipline in the opinion of many social scientists, of users and survivors of psychiatry and critical psychiatrists. Like everywhere, in the discussion of medicalization there are many pros and cons as well as intermediate positions. When we discuss medicalization, we should have a very clear view, what medicalization can mean in a concrete way for an individual and which other factors are connected with medicalization; so we can move from talk to action. Medicalization and irresponsibility often go hand in hand. Psychiatry as a scientific discipline cannot do justice to the expectation of solving mental problems that are largely of a social nature. Its propensity and practice are not * Lecture, June 29, 2010, presented to the congress ‘The real person’, organized by the University of Preston (Lancashire), Institute for Philosophy, Diversity and Mental Health, in cooperation with the European Network of (ex-) Users and Survivors of Psychiatry (ENUSP) in Manchester within the Parallel Session ‘Psychiatric Medicalization: User and Survivor Perspectives’ (together with John Sadler, Professor of Medical Ethics & Clinical Sciences at the UT Southwestern, Dallas, and Jan Verhaegh, philosopher and ENUSP board-member, Valkenburg aan de Geul, The Netherlands). -

United for a Revolution in Mental Health Care

Winter 2009-10 www.MindFreedom.org Protesters give a Mad Pride injection to the psychiatric industry directly outside the doors of the American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting during a “Festival of Resistance” co-sponsored by MindFreedom International and the California Network of Mental Health Clients. See page 8 for more. Victory! MindFreedom Helps Ray Sandford Stop His Forced Electroshock Mad Pride in Media Launched: Directory of Alternative Mental Health Judi Chamberlin Leads From Hospice United for a Revolution in Mental Health Care www.MindFreedom.org Published PbyAGE MFI • MindFreedom International Wins Campaigns for Human Rights and From the Executive Director: Everyone Has Something To Offer Alternatives in the Mental Health System Please join! BY DAVID W. OAKS all psychiatric oppression “BY This is a TUESDAY.” MindFreedom International Sponsor Group or Affiliate has a Because of generous support from place where www.MindFreedom.org (MFI) is one of the few groups liaison on the MFI Support Coalition MindFreedom groups and members, “So,” Judi said, “that’s what I MindFreedom in the mental health field that is Advisory Council. [email protected] in the last few months I have had want. By Tuesday.” members can post to forums independent with no funding from MFI’s mission: “In a spirit of the privilege of visiting MindFree- In that spirit, here are some tips for and blogs that are or links to governments, mental mutual cooperation, MindFreedom MindFreedom International dom International (MFI) activists in our members in effective leadership open to public health providers, drug companies, International leads a nonviolent 454 Willamette, Suite 216 Norway, Maine, Massachusetts, Min- in MindFreedom International, for a view. -

Abolishing the Concept of Mental Illness

ABOLISHING THE CONCEPT OF MENTAL ILLNESS In Abolishing the Concept of Mental Illness: Rethinking the Nature of Our Woes, Richard Hallam takes aim at the very concept of mental illness, and explores new ways of thinking about and responding to psychological distress. Though the concept of mental illness has infiltrated everyday language, academic research, and public policy-making, there is very little evidence that woes are caused by somatic dysfunction. This timely book rebuts arguments put forward to defend the illness myth and traces historical sources of the mind/body debate. The author presents a balanced overview of the past utility and current disadvantages of employing a medical illness metaphor against the backdrop of current UK clinical practice. Insightful and easy to read, Abolishing the Concept of Mental Illness will appeal to all professionals and academics working in clinical psychology, as well as psychotherapists and other mental health practitioners. Richard Hallam worked as a clinical psychologist, researcher, and lecturer until 2006, mainly in the National Health Service and at University College London and the University of East London. Since then he has worked independently as a writer, researcher, and therapist. ABOLISHING THE CONCEPT OF MENTAL ILLNESS Rethinking the Nature of Our Woes Richard Hallam First published 2018 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2018 Richard Hallam The right of Richard Hallam to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Antipsychiatry Movement 29 Wikipedia Articles

Antipsychiatry Movement 29 Wikipedia Articles PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 29 Aug 2011 00:23:04 UTC Contents Articles Anti-psychiatry 1 History of anti-psychiatry 11 Involuntary commitment 19 Involuntary treatment 30 Against Therapy 33 Dialectics of Liberation 34 Hearing Voices Movement 34 Icarus Project 45 Liberation by Oppression: A Comparative Study of Slavery and Psychiatry 47 MindFreedom International 47 Positive Disintegration 50 Radical Psychology Network 60 Rosenhan experiment 61 World Network of Users and Survivors of Psychiatry 65 Loren Mosher 68 R. D. Laing 71 Thomas Szasz 77 Madness and Civilization 86 Psychiatric consumer/survivor/ex-patient movement 88 Mad Pride 96 Ted Chabasinski 98 Lyn Duff 102 Clifford Whittingham Beers 105 Social hygiene movement 106 Elizabeth Packard 107 Judi Chamberlin 110 Kate Millett 115 Leonard Roy Frank 118 Linda Andre 119 References Article Sources and Contributors 121 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 123 Article Licenses License 124 Anti-psychiatry 1 Anti-psychiatry Anti-psychiatry is a configuration of groups and theoretical constructs that emerged in the 1960s, and questioned the fundamental assumptions and practices of psychiatry, such as its claim that it achieves universal, scientific objectivity. Its igniting influences were Michel Foucault, R.D. Laing, Thomas Szasz and, in Italy, Franco Basaglia. The term was first used by the psychiatrist David Cooper in 1967.[1] Two central contentions -

Space, Politics, and the Uncanny in Fiction and Social Movements

MADNESS AS A WAY OF LIFE: SPACE, POLITICS AND THE UNCANNY IN FICTION AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS Justine Lutzel A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2013 Committee: Ellen Berry, Advisor Francisco Cabanillas Graduate Faculty Representative Ellen Gorsevski William Albertini © 2013 Justine Lutzel All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ellen Berry, Advisor Madness as a Way of Life examines T.V. Reed’s concept of politerature as a means to read fiction with a mind towards its utilization in social justice movements for the mentally ill. Through the lens of the Freudian uncanny, Johan Galtung’s three-tiered systems of violence, and Gaston Bachelard’s conception of spatiality, this dissertation examines four novels as case studies for a new way of reading the literature of madness. Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House unveils the accusation of female madness that lay at the heart of a woman’s dissatisfaction with domestic space in the 1950s, while Dennis Lehane’s Shutter Island offers a more complicated illustration of both post-traumatic stress syndrome and post-partum depression. Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain and Curtis White’s America Magic Mountain challenge our socially- accepted dichotomy of reason and madness whereby their antagonists give up success in favor of isolation and illness. While these texts span chronology and geography, each can be read in a way that allows us to become more empathetic to the mentally ill and reduce stigma in order to effect change. -

The Electroshock Quotationary®

The Electroshock Quotationary® Leonard Roy Frank, Editor Publication date: June 2006 Copyright © 2006 by Leonard Roy Frank. All Rights Reserved. Dedicated to everyone committed to ending the use of electroshock everywhere and forever The Campaign for the Abolition of Electroshock in Texas (CAEST) was founded in Austin during the summer of 2005. The Electroshock Quotationary (ECTQ) was created to support the organization’s opposition to electroshock by informing the public, through CAEST’s website, about the nature of electroshock, its history, why and how it’s used, its effects on people, and the efforts to promote and stop its use. The editor plans to regularly update ECTQ with suitable materials when he finds them or when they are brought to his attention. In this regard he invites readers to submit original and/or published materials for consideration (e-mail address: [email protected]). CONTENTS Acknowledgements Introduction: The Essentials (7 pages) Text: Chronologically Arranged Quotations (146 pages) About the Editor ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For their many kindnesses, contributions and suggestions to The Electroshock Quotationary, I am most grateful to Linda Andre, Ronald Bassman, Margo Bouer, John Breeding, Doug Cameron, Ted Chabasinski, Lee Coleman, Alan Davisson, Dorothy Washburn Dundas, Sherry Everett, John Friedberg, Janet Gotkin, Ben Hansen, Wade Hudson, Juli Lawrence, Peter Lehmann, Diann’a Loper, Rosalie Maggio, Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson, Carla McKague, Jim Moore, Bob Morgan, David Oaks, Una Parker, Marc Rufer, Sherri Schultz, Eileen Walkenstein, Ann Weinstock, Don Weitz, and Rich Winkel. INTRODUCTION: THE ESSENTIALS I. THE CONTROVERSY Electroshock (also known as shock therapy, electroconvulsive treatment, convulsive therapy, ECT, EST, and ECS) is a psychiatric procedure involving the induction of a grand mal seizure, or convulsion, by passing electricity through the brain. -

The Search for Political Identity by People with Psychiatric Diagnoses

William & Mary Law Review Volume 44 (2002-2003) Issue 3 Disability and Identity Conference Article 9 February 2003 "Discredited" and "Discreditable:" The Search for Political Identity by People with Psychiatric Diagnoses Susan Stefan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Disability Law Commons Repository Citation Susan Stefan, "Discredited" and "Discreditable:" The Search for Political Identity by People with Psychiatric Diagnoses, 44 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 1341 (2003), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/ wmlr/vol44/iss3/9 Copyright c 2003 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr "DISCREDITED" AND "DISCREDITABLE": THE SEARCH FOR POLITICAL IDENTITY BY PEOPLE WITH PSYCHIATRIC DIAGNOSES SUSAN STEFAN* You're never the same-mental health diagnosis is an opinion and attitude. You cannot cure or have remissionfrom others' attitudesof rejection.1 Friendsand family-they don't understandmy illness/disability- they think I am getting away with something-that there is nothing wrong with me.2 INTRODUCTION Identity matters. In particular, identity matters to people who are stigmatized and stereotyped because they belong to a socially disfavored group. Although individual members of these groups may have very different ideas about how to respond to prejudice and mistreatment, the matter of identity itself-membership in the group-is generally not at issue. Justice Clarence Thomas and the Reverend Jesse Jackson may have sharply conflicting ideas about the meaning of being an African American in our society, but the identity of each man as an African American is hardly open to question. -

The Disability Studies Reader

CHAPTER 7 A Mad Fight: Psychiatry and Disability Activism Bradley Lewis 100 SUMMARY The Mad Pride movement is made up of activists resisting and critiquing physician-centered psychiatric systems, finding alternative approaches to mental health and helping people choose minimal involvement with psychiatric institutions. They believe mainstream psychiatry over exaggerates pathology and forces conformity though diagnosis and treatment. In this chapter, Bradley Lewis highlights the political and epistemological similarities between the Mad Pride movement and other areas of disability studies. For instance, the social categories of normal and abnormal legitimize the medicalization of different bodies and minds and exert pressure on institutions to stay on the side of normality, or in this case, sanity. Lewis briefly traces the historical roots of Mad Pride to show how diagnoses of insanity were often political abuses aimed at normalizing differing opinions and experiences. The movement entered into the debate to fight involuntary hospitalization and recast mental illness as a myth rather than an objective reality. Today’s Mad Pride often works within mental health services systems by bringing together “consumers” (rather than “survivors” or “ex-patients”) who contribute real input for psychiatric policy. Nevertheless, Mad Pride still wages an epistemological and political struggle with psychiatry, which has undergone a “scientific revolution” that values “objective” data and undervalues humanistic inquiries. For example, biopsychiatric methods led to Prozac-type drugs being prescribed to 67.5 million Americans between 1987 and 2002. Mad Pride staged a hunger strike to protest the reduction of mental illness to a brain disease, arguing this model couldn’t be proved by evidence and limited consumers’ options for treatments like therapy or peer-support. -

Dangerous Gifts: Towards a New Wave of Mad Resistance

Dangerous Gifts: Towards a New Wave of Mad Resistance Jonah Bossewitch Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 ©2016 Jonah Bossewitch All rights reserved ABSTRACT Dangerous Gifts: Towards a New Wave of Mad Resistance Jonah Bossewitch This dissertation examines significant shifts in the politics of psychiatric resistance and mental health activism that have appeared in the past decade. This new wave of resistance has emerged against the backdrop of an increasingly expansive diagnostic/treatment para- digm, and within the context of activist ideologies that can be traced through the veins of broader trends in social movements. In contrast to earlier generations of consumer/survivor/ex-patient activists, many of whom dogmatically challenged the existence of mental illness, the emerging wave of mad activists are demanding a voice in the production of psychiatric knowledge and greater control over the narration of their own identities. After years as a participant-observer at a leading radical mental health advocacy organization, The Icarus Project, I present an ethnography of conflicts at sites including Occupy Wall Street and the DSM-5 protests at the 2012 American Psychiatric Association conference. These studies bring this shift into focus, demonstrate how non-credentialed stakehold- ers continue to be silenced and marginalized, and help us understand the complex ideas these activists are expressing. This new wave of resistance emerged amidst a revolution in communication technologies, and throughout the dissertation I consider how activists are utilizing communications tools, and the ways in which their politics of resistance res- onate deeply with the communicative modalities and cultural practices across the web. -

Psychiatric Disability and Rhetoricity: Refiguring Rhetoric and Composition Studies in the 21St Century

Psychiatric Disability and Rhetoricity: Refiguring Rhetoric and Composition Studies in the 21st Century Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Elizabeth Marie Brewer, M.A., B.A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Brenda Jo Brueggemann, Advisor Dr. Cynthia L. Selfe Dr. Maurice Stevens Copyright by Elizabeth Marie Brewer 2014 Abstract “Psychiatric Disability and Rhetoricity: Refiguring Rhetoric and Composition Studies in the 21st Century” examines the ways in which mental health activists in the consumer/survivor/ex-patient (c/s/x) movement reframe medical models of mental illness by asserting their lived experience as valuable ontology. I use a mixed qualitative research methodology to analyze discussion board posts and vernacular videos as well as data from interviews I conducted with c/s/x activists. Seeking to correct the absence in rhetoric and composition of first-person perspectives from psychiatric disabled people, I demonstrate how disability studies provides a position from which the rhetorical agency of psychiatrically disabled people can be established. In Chapter 1, “Naming Psychiatric Disability and Moving Beyond the Ethos Problem,” I contextualize the absence of psychiatric disabled perspectives in the history of rhetoric. By demonstrating that the logic of psychiatric-disability-as-an-ethos-problem functions as an enthymeme that warrants re-examination, I denaturalize discourses that assume psychiatrically disabled rhetors have ethos problems. An interchapter follows Chapter 1, and provides an overview of Chapters 2-5 and my mixed, emergent qualitative research methodology. -

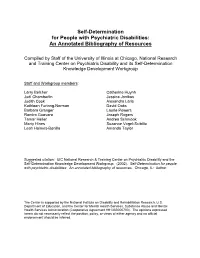

Self-Determination for People with Psychiatric Disabilities: an Annotated Bibliography of Resources

Self-Determination for People with Psychiatric Disabilities: An Annotated Bibliography of Resources Compiled by Staff of the University of Illinois at Chicago, National Research and Training Center on Psychiatric Disability and its Self-Determination Knowledge Development Workgroup Staff and Workgroup members: Larry Belcher Catherine Huynh Judi Chamberlin Jessica Jonikas Judith Cook Alexandra Laris Kathleen Furlong-Norman David Oaks Barbara Granger Laurie Powers Ramiro Guevara Joseph Rogers Tamar Heller Andrea Schmook Marty Hines Suzanne Vogel-Scibilia Leah Holmes-Bonilla Amanda Taylor Suggested citation: UIC National Research & Training Center on Psychiatric Disability and the Self-Determination Knowledge Development Workgroup. (2002). Self-Determination for people with psychiatric disabilities: An annotated bibliography of resources. Chicago, IL: Author. The Center is supported by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research, U.S. Department of Education, and the Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (Cooperative Agreement #H133B000700). The opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the position, policy, or views of either agency and no official endorsement should be inferred. History, Definitions, and Principles of Self-Determination & Recovery Alliance for Self-Determination, Center on Self-Determination, Oregon Health Sciences University. (1999). National Leadership Summit on Self-Determination and Consumer-Direction and Control: Invited papers.