Download (1008Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Programma Arena Castello Di Bari

Bif&st 2020 ItaliaFilmFest | Evento speciale | Ingresso € 5,00 IL PROGRAMMA LUOGO PER LUOGO SABATO 22 DOMENICA 23 LUNEDÌ 24 MARTEDÌ 25 MERCOLEDÌ 26 GIOVEDÌ 27 VENERDÌ 28 SABATO 29 20:00 20:00 20:00 20:00 20:00 20:00 20:00 20:00 Hammamet Il signor Diavolo Il primo natale La rivincita A mano disarmata Figli L’immortale Pinocchio di Gianni Amelio di Pupi Avati di Ficarra e Picone di Leo Muscato di Claudio Bonivento di Giuseppe Bonito di Marco D’Amore di Matteo Garrone Italia 2020, 127’ v.it. Italia 2019, 90’ Italia 2019, 100’ Italia 2020, 87’ v.it. Italia 2019, 108’ Italia 2020, 99’ Italia 2019, 116’ Italia-Francia 2019, 125’ v.it. sott. ingl. v.it. sott. ingl. fuori concorso v.it. sott. ingl. v.it. sott. ingl. v.it v.it. sott. ingl. PIERFRANCESCO FAVINO ANTONIO, PUPI, FRANCESCO FRIGERI MILENA MANCINI PAOLA CORTELLESI MARCO D’AMORE MATTEO GARRONE Premio Vittorio Gassman TOMMASO AVATI Premio Dante Ferretti Premio Alida Valli Premio Mariangela Melato Premio Ettore Scola PAOLO DEL BROCCO Premio Tonino Guerra per il cinema Opere Prime e Seconde Premio Franco Cristaldi LUAN AMELIO UJKAJ Opere Prime e seconde Premio Giuseppe Rotunno ROBERTO BENIGNI Premio Alberto Sordi NICOLA PIOVANI MASSIMO CANTINI PARRINI Premio Ennio Morricone Premio Piero Tosi 22:30 22:30 22:30 22:30 22:30 22:30 22:30 22:30 Il traditore Gli anni più belli Martin Eden The Nest La famosa invasione 5 è il numero 18 Regali Sole di Marco Bellocchio di Gabriele Muccino di Pietro Marcello (Il Nido) degli orsi in Sicilia perfetto di Francesco Amato di Carlo Sironi Italia-Francia-Brasile-Germania Italia 2020, 130’ Italia 2019, 129’ di Roberto De Feo di Lorenzo Mattotti di Igort Italia 2020, 115’ Italia-Polonia 2019, 103’ v.it. -

ME,YOUBY BILLE AUGUST a Film Based on the Novel “Tu, Mio” by ERRI DE LUCA SYNOPSIS

ME,YOUBY BILLE AUGUST A Film based On The Novel “Tu, Mio” by ERRI DE LUCA SYNOPSIS Ischia, 1955. In the waters of the island in the bay of Naples, Marco (16) Caia is Jewish. Marco does not have these prejudices, on the contrary, spends his days sailing with Nicola (52), a hardened fisherman who tells this discovery pushes him to delve into the girl’s life even more. A stories about the sea and the war, that is still very fresh in his memory. beautiful complicity is established between the two in which Caia reveals Marco is different from the other boys, he prefers spending his time her painful past, with a childhood stolen by the SS and a father who in the company of the hermetic Nicola rather than going to the beach, preferred to throw his daughter out of a train in Yugoslavia, rather having courting girls or bathing in the ocean like his peers. Shy and curious, he her to experience the horrors of a concentration camp. takes advantage of his holidays on the Italian island to fill his eyes with Marco’s gestures remind Caia of her father: his protective attitudes, the images of a world that is so distant from his native London or from the way he kisses her on the forehead, the sound of his voice when he the gloomy boarding school in Scotland where his family sheltered Marco pronounces her name in Romanian, Chaiele. Next to him she feels the to protect him from the bombings. presence of her father, even though Marco is just a slender boy 4 years On vacation with his parents at his maternal uncle’s house, he will live younger than her. -

Una Produzione R.T.I. Prodotto Da RIZZOLI AUDIOVISIVI DIEGO

una produzione R.T.I. prodotto da RIZZOLI AUDIOVISIVI DIEGO ABATANTUONO in con ALESSIA MARCUZZI e ANTONIO CATANIA FABIO FULCO VITTORIA PIANCASTELLI GENNARO DIANA ELENA CANTARONE UGO CONTI RICCARDO ZINNA e con DINO ABBRESCIA con la partecipazione di LUIGI MARIA BURRUANO con la partecipazione di AMANDA SANDRELLI Soggetto di serie GRAZIANO DIANA, ENRICO OLDOINI, SALVATORE BASILE, GIANCARLO DE CATALDO Soggetti e sceneggiature GIANCARLO DE CATALDO, GRAZIANO DIANA, FRANCO FERRINI, ENRICO OLDOINI, CARLO BELLAMIO, MARCO TIBERI Prodotto da ANGELO RIZZOLI Regia di ENRICO OLDOINI serie tv in 4 puntate in onda in prima serata su CANALE 5 venerdì 4, 11, 18 e 25 maggio 2007 CREDITI NON CONTRATTUALI CAST ARTISTICO PRINCIPALE Diego Abatantuono (Giudice Diego Mastrangelo) Alessia Marcuzzi (Claudia Nicolai) Antonio Catania (Uelino) Fabio Fulco (Paolo Parsani) Vittoria Piancastelli (Cristiana Mastrangelo) Gennaro Diana (Naselli) Dino Abbrescia (Gerardo) Elena Cantarone (Finzi) Ugo Conti (Palmieri) Riccardo Zinna (Frappampina) Luigi Maria Burruano (Procuratore De Cesare) Melissa Satta (Francesca) Amanda Sandrelli (Federica Denza) CREDITI NON CONTRATTUALI CAST TECNICO Soggetto di serie GRAZIANO DIANA ENRICO OLDOINI SALVATORE BASILE GIANCARLO DE CATALDO Soggetti e Sceneggiature CARLO BELLAMIO GIANCARLO DE CATALDO GRAZIANO DIANA FRANCO FERRINI ENRICO OLDOINI MARCO TIBERI casting director FRANCO ALBERTO CUCCHINI Face ON suono FABRIZIO ANDREUCCI organizzatore di produzione EMANUELE EMILIANI costumi PATRIZIA CHERICONI FLORENCE EMIR scenografia MARISA RIZZATO musiche PIVIO & ALDO DE SCALZI montaggio FABIO e JENNY LOUTFY fotografia SANDRO GROSSI organizzatore generale ALESSANDRO LOY delegato di produzione R.T.I. FABIANA MOCCIA produttori R.T.I. MARCO MARCHIONNI ALESSANDRA SILVERI prodotto da ANGELO RIZZOLI per RIZZOLI AUDIOVISIVI S.p.A. regia di ENRICO OLDOINI UFFICIO STAMPA RIZZOLI AUDIOVISIVI: UFFICIO STAMPA MEDIASET: ENRICO LUCHERINI Maria Cristina de Caro TEL. -

DIVISMO E RAPPRESENTAZIONE DELLA SESSUALITÀ NEL CINEMA ITALIANO (1948-1978) a Cura Di Laura Busetta E Federico Vitella

E DEI MEDIA IN ITALIA IN MEDIA DEI E CINEMA DEL CULTURE E STORIE SCHERMI STELLE DI MEZZO SECOLO: DIVISMO E RAPPRESENTAZIONE DELLA SESSUALITÀ NEL CINEMA ITALIANO (1948-1978) a cura di Laura Busetta e Federico Vitella ANNATA IV NUMERO 8 luglio dicembre 2020 SCHERMI 8 - 2020 Schermi è pubblicata sotto Licenza Creative Commons 118 CLAUDIA CARDINALE SFIDANZATA D’ITALIA - Jandelli CLAUDIA CARDINALE SFIDANZATA D’ITALIA Cristina Jandelli(Università degli Studi di Firenze) The year 1967 constitutes a turning point for the public image of Claudia Cardinale. Shortly before the tabloid press finds the birth certificate of her illegitimate child in London, the producer Franco Cristaldi hurries to marry her in the United States and soon he will affiliate the child: but the divistic construct of the “fiancée of Italy” has been shattered. This article aims to reconstruct not what actually happened but what the tabloid press almost destroyed. In 1962, in fact, an impressive international image operation, called by the producer Franco Cristaldi and Fabio Rinaudo, the star’s press agent, “SuperCardinale”, had conceived a star system product resulting from a detailed image strategy. Even if the public story of the diva had been overwhelmed by the revelations of the tabloid press, her career did not break into pieces. A new story was already in place. The Vides star shows off in the pages of the popular magazines along with other single mothers of the Italian show business. On May 6, 1967 she takes part to an audience with the Pope Paul VI wearing a miniskirt: in so doing, she exploits the character of the penitent Magdalene to promote her role as an ex prostitute in “Once Upon a Time in the West” by Sergio Leone. -

La Cultura Italiana

LA CULTURA ITALIANA FEDERICO FELLINI (1920-1993) This month’s essay continues a theme that several prior essays discussed concerning fa- mous Italian film directors of the post-World War II era. We earlier discussed Neorealism as the film genre of these directors. The director we are considering in this essay both worked in that genre and carried it beyond its limits to develop an approach that moved Neoreal- ism to a new level. Over the decades of the latter-half of the 20th century, his films became increasingly original and subjective, and consequently more controversial and less commercial. His style evolved from Neorealism to fanciful Neorealism to surrealism, in which he discarded narrative story lines for free-flowing, free-wheeling memoirs. Throughout his career, he focused on his per- sonal vision of society and his preoccupation with the relationships between men and women and between sex and love. An avowed anticleric, he was also deeply concerned with personal guilt and alienation. His films are spiced with artifice (masks, masquerades and circuses), startling faces, the rococo and the outlandish, the prisms through which he sometimes viewed life. But as Vincent Canby, the chief film critic of The New York Times, observed in 1985: “What’s important are not the prisms, though they are arresting, but the world he shows us: a place whose spectacularly grand, studio-built artificiality makes us see the interior truth of what is taken to be the ‘real’ world outside, which is a circus.” In addition to his achievements in this regard, we are also con- sidering him because of the 100th anniversary of his birth. -

Italy Cinema Giant, Franco Cristaldi's Tuscany Villa up for Sale

Italy Cinema Giant, Franco Cristaldi’s Tuscany Villa Up For Sale (EXCLUSIVE) SELLER: Cristaldi Family REAL ESTATE AGENCY: Columbus International at Keller Williams NYC LOCATION: Between Volterra and San Gimignano (Italy) PRICE: Euros 5,900,000 (USD 6,900,000) SIZE: 30,903 Square Feet, 22+ bedrooms GALLERY: 9 Images attached NOTES: Franco Cristaldi, a three-time Oscar winner, awarded for Best Foreign Film with Federico Fellini's Amarcord and Giuseppe Tornatore's Cinema Paradiso, became the owner of Villa di Ulignano in 1967, purchasing it from the State at a public auction after decades of abandon. Now, more than 25 years later after his death, this cinematic hamlet of houses, distributed on approximately 4 acres of land, has popped up for sale with an asking price of $6,960,000 million. Perched atop the hill of Ulignano, the property is an outstanding 17th century villa surrounded by a magnificent garden with centuries-old trees. The manor home is part of a 17-acre property between Volterra, the closest town, and San Gimignano, at the heart of the triangle composed of Siena, Florence and Pisa. The spirit of the place enchanted one of Italy's greatest artists of the 20th century. While traveling through these hills on a quest to find locations for his latest movie, Italian theatre, opera and cinema director, Luchino Visconti, best known for his films Ossessione, Senso, Rocco and His Brothers, The Leopard and Death in Venice, came across the Villa di Ulignano and fell in love with it. One of the founding fathers of the Italian Neorealist movement, Visconti chose Villa di Ulignano for his movie Sandra, with Claudia Cardinale and Jean Sorel, all shot in Volterra, winner of the Golden Lion at the 30th International Film Festival of Venice. -

Development Programme Book of Projects 2009

Dvbook of projects 2009 Development Programme MINISTERO PER I BENI E LE ATTIVITÀ CULTURALI DIREZIONE GENERALE PER IL CINEMA In 2008, the specific aspects of the so-called TorinoFilmLab invites filmmakers to enter a “cinema system” rooted within Torino and Piedmont collaborative process throughout the whole path - characterised by numbers of successful initiatives that brings a story from the intimacy of the artist’s such as Film Commission Torino Piemonte, the mind to the possibility of sharing it with the public. National Cinema Museum, the Torino Film Festival, Script&Pitch Workshops - represented a strong At every step, there are chances to explore, to doubt, basis for the creation of a permanent international to change, to improve, and at every step, there is laboratory, TorinoFilmLab, destined to accompany someone that can listen, help, bring advice. There talents for a reasonable amount of time through is a whole bunch of people out there that can different steps: starting from when the film’s make a filmmakers’ life, if not easier, at least richer story and structure are first thought of, following in opportunities, and this mostly before the film is through the development stage, up to the process made. People who share a passion for stories, and of financing and possibly rewarding some of the are willing to help creating the right context so that selected projects with a production grant. stories can travel far: scriptwriters, story editors, directors, directors of photography, sound designers, TorinoFilmLab Thanks to the support of the Italian Ministero per producers, sales agents, distributors, financiers. i Beni e le Attività Culturali, the Regione Piemonte TorinoFilmLab works to facilitate these encounters, and Città di Torino we have found the necessary each one at the right time. -

Ennio Morricone

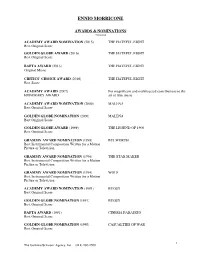

ENNIO MORRICONE AWARDS & NOMINATIONS *selected ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2015) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD (2016) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (2016) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Original Music CRITICS’ CHOICE AWARD (2016) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Best Score ACADEMY AWARD (2007) For magnificent and multifaceted contributions to the HONORARY AWARD art of film music ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2000) MALENA Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (2000) MALENA Best O riginal Score GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD (1999) THE LEGEND OF 1900 Best Original Score GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1998) BULWORTH Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or Television GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1996) THE STAR MAKER Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or Television GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1994) WOLF Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or Television ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1991) BUGSY Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1991) BUGSY Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1991) CINEMA PARADISO Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1990) CASUALTIES OF WAR Best Original Score 1 The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 ENNIO MORRICONE ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1987) THE UNTOUCHABLES Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1988) THE UNTOUCHABLES Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1988) THE UNTOUCHABLES Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1987) THE MISSION Best Original Score ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1986) THE MISSION Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD (1986) THE MISSION Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1985) ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1985) ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1980) DAYS OF HEAVEN Anthony Asquith Award fo r Film Music ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1979) DAYS OF HEAVEN Best Original Score MOTION PICTURES THE HATEFUL EIGHT Richard N. -

Hofstra University Film Library Holdings

Hofstra University Film Library Holdings TITLE PUBLICATION INFORMATION NUMBER DATE LANG 1-800-INDIA Mitra Films and Thirteen/WNET New York producer, Anna Cater director, Safina Uberoi. VD-1181 c2006. eng 1 giant leap Palm Pictures. VD-825 2001 und 1 on 1 V-5489 c2002. eng 3 films by Louis Malle Nouvelles Editions de Films written and directed by Louis Malle. VD-1340 2006 fre produced by Argosy Pictures Corporation, a Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer picture [presented by] 3 godfathers John Ford and Merian C. Cooper produced by John Ford and Merian C. Cooper screenplay VD-1348 [2006] eng by Laurence Stallings and Frank S. Nugent directed by John Ford. Lions Gate Films, Inc. producer, Robert Altman writer, Robert Altman director, Robert 3 women VD-1333 [2004] eng Altman. Filmocom Productions with participation of the Russian Federation Ministry of Culture and financial support of the Hubert Balls Fund of the International Filmfestival Rotterdam 4 VD-1704 2006 rus produced by Yelena Yatsura concept and story by Vladimir Sorokin, Ilya Khrzhanovsky screenplay by Vladimir Sorokin directed by Ilya Khrzhanovsky. a film by Kartemquin Educational Films CPB producer/director, Maria Finitzo co- 5 girls V-5767 2001 eng producer/editor, David E. Simpson. / una produzione Cineriz ideato e dirètto da Federico Fellini prodotto da Angelo Rizzoli 8 1/2 soggètto, Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano scenegiatura, Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio V-554 c1987. ita Flaiano, Brunello Rondi. / una produzione Cineriz ideato e dirètto da Federico Fellini prodotto da Angelo Rizzoli 8 1/2 soggètto, Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano scenegiatura, Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio V-554 c1987. -

Hliebing Dissertation Revised 05092012 3

Copyright by Hans-Martin Liebing 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Hans-Martin Liebing certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Transforming European Cinema : Transnational Filmmaking in the Era of Global Conglomerate Hollywood Committee: Thomas Schatz, Supervisor Hans-Bernhard Moeller Charles Ramírez Berg Joseph D. Straubhaar Howard Suber Transforming European Cinema : Transnational Filmmaking in the Era of Global Conglomerate Hollywood by Hans-Martin Liebing, M.A.; M.F.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 Dedication In loving memory of Christa Liebing-Cornely and Martha and Robert Cornely Acknowledgements I would like to thank my committee members Tom Schatz, Charles Ramírez Berg, Joe Straubhaar, Bernd Moeller and Howard Suber for their generous support and inspiring insights during the dissertation writing process. Tom encouraged me to pursue this project and has supported it every step of the way. I can not thank him enough for making this journey exciting and memorable. Howard’s classes on Film Structure and Strategic Thinking at The University of California, Los Angeles, have shaped my perception of the entertainment industry, and having him on my committee has been a great privilege. Charles’ extensive knowledge about narrative strategies and Joe’s unparalleled global media expertise were invaluable for the writing of this dissertation. Bernd served as my guiding light in the complex European cinema arena and helped me keep perspective. I consider myself very fortunate for having such an accomplished and supportive group of individuals on my doctoral committee. -

Federico Fellini: a Life in Film

Federico Fellini: a life in film Federico Fellini was born in Rimini, the Marché, on 20th January 1920. He is recognized as one of the greatest and most influential filmmakers of all time. His films have ranked in polls such as ‘Cahiers du cinéma’ and ‘Sight & Sound’, which lists his 1963 film “8½” as the 10th-greatest film. Fellini won the ‘Palme d'Or’ for “La Dolce Vita”, he was nominated for twelve 'Academy Awards', and won four in the category of 'Best Foreign Language Film', the most for any director in the history of the Academy. He received an honorary award for 'Lifetime Achievement' at the 65th Academy Awards in Los Angeles. His other well-known films include 'I Vitelloni' (1953), 'La Strada' (1954), 'Nights of Cabiria' (1957), 'Juliet of the Spirits' (1967), 'Satyricon' (1969), 'Roma' (1972), 'Amarcord' (1973) and 'Fellini's Casanova' (1976). In 1939, he enrolled in the law school of the University of Rome - to please his parents. It seems that he never attended a class. He signed up as a junior reporter for two Roman daily papers: 'Il Piccolo' and 'lI Popolo di Roma' but resigned from both after a short time. He submitted articles to a bi- weekly humour magazine, 'Marc’Aurelio', and after 4 months joined the editorial board, writing a very successful regular column “But are you listening?” Through this work he established connections with show business and cinema and he began writing radio sketches and jokes for films. He achieved his first film credit - not yet 20 - as a comedy writer in “Il pirato sono io” (literally, “I am a pirate”), translated into English as “The Pirate’s Dream”. -

20210514092607 Amarcorden

in collaborazione con: The main places linked to Fellini in Rimini Our location 12 31 Cimitero Monumentale Trento vialeTiberio 28 via Marecchia Matteotti viale Milano Venezia Torino 13 via Sinistra del Porto 27 Bologna Bastioni Settentrionali Genova Ravenna via Ducale via Destra del Porto Rimini Piacenza Firenze Ancona via Dario Campana Perugia Ferrara Circonvallazione Occidentale 1 Parma 26 Reggio Emilia viale Principe piazzale Modena via dei Mille dei via Amedeo Fellini Roma corso d’Augusto via Cavalieri via via L. Toninivia L. corso Giovanni XXIII Bari Bologna viale Valturio 14 Ravenna largo 11 piazza 19 21 Napoli Valturio Malatesta 15piazza piazza Cavour via GambalungaFerrari Forlì 3via Gambalunga Cesena via Cairoli 9 Cagliari Rimini via G. Bruno Catanzaro Repubblica di San Marino 2 7 20 22 Tintori lungomare Palermo via Sigismondo via Mentana Battisti Cesare piazzale i via Garibaldi via Saffi l a piazza Roma via n 5 o Tre Martiri 6 i 17 viaTempio Malatestiano d i via IV Novembre via Dante 23 r e 18 4 piazzale Covignano M via Clementini i Kennedy n o i t s a 16 B via Castelfidardo corso d’Augusto via Brighenti piazzale The main places linked to Fellini near Rimini 10 8 Gramsci via Roma Anfiteatro Arco e lungomare Murri lungomare l d’Augusto Bellaria a Bastioni Orientali n Igea Marina o Gambettola i viale Amerigo Vespucci Amerigo viale 33 d i r 25 e M e via S. Brancaleoni n o i z a l l a via Calatafimi Santarcangelo v n via XX Settembre o di Romagna c r piazza i 24 Ospedale 30Aeroporto viale Tripoli C Marvelli 32 Rimini via della Fiera viale Tripoli 29 Poggio Berni Rimini 18 Piazza Tre Martiri (formerly Piazza G.