La Cultura Italiana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ames Dashow-Thomas Delio

ames Dashow-Thomas Delio- lonN Forvr-t-t , rrurr Srrvrn Snrcx, PERCUSSToN Mnuno Mnun, TRUMPET Luctl Bovl, nane Arrcx Kents, etaNo llcqurs l-rNorn, erANo Srrone SrnrcnEn, etnNo fAMES DASHOW . THOMAS DEIIO Program Notes: fames Dashow MORFOI-OCIE (Morphologies) for trumpet player and computer is the most recent (as of fames Dashow 1994\ ol Dashow's series of works for soloist with digitally synthesized electronic sounds. lt presents the composer in a lyrical vein; the musical echoes of Miles Davis and of Chet Baker I . Morfologie for trumpet-player and computer 1'tss:1 14107 are purely intentional, Dashow having subtitled the piece ln Memoriam to these two superb musicians who had so much to do with the composer's early musical formation in the 1950's, 2. Punti di Visfa No. 2 for piano solo (rszo, revised 1990) 12:32 especially the young Baker. The piece is divided into two major parts. The first is very active and highly charged, but with for harp and (rggz) 13:36 3. Reconstructions computer suddenfallingsoffofenergyandgradualreturnstoevenhigherlevelsofintensity. The trumpet player begins on cornet, playfully using a harmon mute at first; the intertwining of Thomas Delio electronic sounds specially designed to go with the harmon muted cornet creates a lively counterpoint of gesture and line that spills over into the the first open cornet 4. anti-paysage ossot 09:53 section. Waves of energy continue to grow inexorably, overcoming a dramatic interruption to build to a climacticarrival pointwiththesoloistnearthetopoftherangeofthesmall Dtrumpet. The 5. Of for tape trggot 03:34 two protagonists, trumpet and computer, now unexpectedly play exactly together in a powerfully extended phrase that brings this first major part to a close, the electronic sounds 6. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

La Dolce Vita Actress Anita Ekberg Dies at 83

La Dolce Vita actress Anita Ekberg dies at 83 Posted by TBN_Staff On 01/12/2015 (29 September 1931 – 11 January 2015) Kerstin Anita Marianne Ekberg was a Swedish actress, model, and sex symbol, active primarily in Italy. She is best known for her role as Sylvia in the Federico Fellini film La Dolce Vita (1960), which features a scene of her cavorting in Rome's Trevi Fountain alongside Marcello Mastroianni. Both of Ekberg's marriages were to actors. She was wed to Anthony Steel from 1956 until their divorce in 1959 and to Rik Van Nutter from 1963 until their divorce in 1975. In one interview, she said she wished she had a child, but stated the opposite on another occasion. Ekberg was often outspoken in interviews, e.g., naming famous people she couldn’t bear. She was also frequently quoted as saying that it was Fellini who owed his success to her, not the other way around: "They would like to keep up the story that Fellini made me famous, Fellini discovered me", she said in a 1999 interview with The New York Times. Ekberg did not live in Sweden after the early 1950s and rarely visited the country. However, she welcomed Swedish journalists into her house outside Rome and in 2005 appeared on the popular radio program Sommar, and talked about her life. She stated in an interview that she would not move back to Sweden before her death since she would be buried there. On 19 July 2009, she was admitted to the San Giovanni Hospital in Rome after falling ill in her home in Genzano according to a medical official in the hospital's neurosurgery department. -

Un Grand Film : La Strada

LES ECHOS DE SAINT-MAURICE Edition numérique Raphaël BERRA Un grand film : La Strada Dans Echos de Saint-Maurice, 1961, tome 59, p. 277-284 © Abbaye de Saint-Maurice 2012 UN GRAND FILM La Strada « Au terme de nos recherches, il y a Dieu. » FELLINI NOTES SUR L'AUTEUR ET SUR SON ŒUVRE Federico Fellini naît le 20 janvier 1920 à Rimini, station balnéaire des bords de l'Adriatique. Son enfance s'écoule entre le collège des Pères, à Fano, et les vacances à la campagne, à Gambettola, où passent fréquemment les gitans et les forains. Toute l'œuvre de Fellini sera mar quée par le souvenir des gens du voyage, clowns, équi libristes et jongleurs ; par le rythme d'une ville, aussi, où les étés ruisselant du luxe des baigneurs en vacances alternaient avec les hivers mornes et gris, balayés par le vent glacial. Déjà au temps de ses études, Fellini avait manifesté un goût très vif pour la caricature, et ses dessins humo ristiques faisaient la joie de ses camarades. Ce talent l'introduit chez un éditeur de Florence, puis à Rome, où il se rend en 1939. La guerre survient. Sans ressources, Fellini vit d'expédients avant d'ouvrir cinq boutiques de caricatures pour soldats américains. C'est cette période de sa vie qui fera dire à Geneviève Agel (dans une étude remarquable intitulée « Les chemins de Fellini ») : « C'est peut-être à force de caricaturer le visage des hommes qu'il est devenu ce troublant arracheur de masques ». En 1943, Fellini épouse Giulietta Masina. Puis il ren contre Roberto Rossellini qui lui fait tenir le rôle du vagabond dans son film LE MIRACLE. -

Discovery Marche.Pdf

the MARCHE region Discovering VADEMECUM FOR THE TOURIST OF THE THIRD MILLENNIUM Discovering THE MARCHE REGION MARCHE Italy’s Land of Infinite Discovery the MARCHE region “...For me the Marche is the East, the Orient, the sun that comes at dawn, the light in Urbino in Summer...” Discovering Mario Luzi (Poet, 1914-2005) Overlooking the Adriatic Sea in the centre of Italy, with slightly more than a million and a half inhabitants spread among its five provinces of Ancona, the regional seat, Pesaro and Urbino, Macerata, Fermo and Ascoli Piceno, with just one in four of its municipalities containing more than five thousand residents, the Marche, which has always been Italyʼs “Gateway to the East”, is the countryʼs only region with a plural name. Featuring the mountains of the Apennine chain, which gently slope towards the sea along parallel val- leys, the region is set apart by its rare beauty and noteworthy figures such as Giacomo Leopardi, Raphael, Giovan Battista Pergolesi, Gioachino Rossini, Gaspare Spontini, Father Matteo Ricci and Frederick II, all of whom were born here. This guidebook is meant to acquaint tourists of the third millennium with the most important features of our terri- tory, convincing them to come and visit Marche. Discovering the Marche means taking a path in search of beauty; discovering the Marche means getting to know a land of excellence, close at hand and just waiting to be enjoyed. Discovering the Marche means discovering a region where both culture and the environment are very much a part of the Made in Marche brand. 3 GEOGRAPHY On one side the Apen nines, THE CLIMATE od for beach tourism is July on the other the Adriatic The regionʼs climate is as and August. -

Federico Fellini and the Experience of the Grotesque and Carnavalesque – Dis-Covering the Magic of Mass Culture 2013

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Annie van den Oever Federico Fellini and the experience of the grotesque and carnavalesque – Dis-covering the magic of mass culture 2013 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/15114 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Rezension / review Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: van den Oever, Annie: Federico Fellini and the experience of the grotesque and carnavalesque – Dis-covering the magic of mass culture. In: NECSUS. European Journal of Media Studies, Jg. 2 (2013), Nr. 2, S. 606– 615. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/15114. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://doi.org/10.5117/NECSUS2013.2.VAND Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0 Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 NECSUS – EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF MEDIA STUDIES About the author Francesco Di Chiara (University of Ferrara) 2013 Di Chiara / Amsterdam University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly -

October 5, 2010 (XXI:6) Federico Fellini, 8½ (1963, 138 Min)

October 5, 2010 (XXI:6) Federico Fellini, 8½ (1963, 138 min) Directed by Federico Fellini Story by Federico Fellini & Ennio Flaiano Screenplay by Ennio Flaiano, Tullio Pinelli, Federico Fellini & Brunello Rondi Produced by Angelo Rizzoli Original Music by Nino Rota Cinematography by Gianni Di Venanzo Film Editing by Leo Cattozzo Production Design by Piero Gherardi Art Direction by Piero Gherardi Costume Design by Piero Gherardi and Leonor Fini Third assistant director…Lina Wertmüller Academy Awards for Best Foreign Picture, Costume Design Marcello Mastroianni...Guido Anselmi Claudia Cardinale...Claudia Anouk Aimée...Luisa Anselmi Sandra Milo...Carla Hazel Rogers...La negretta Rossella Falk...Rossella Gilda Dahlberg...La moglie del giornalista americano Barbara Steele...Gloria Morin Mario Tarchetti...L'ufficio di stampa di Claudia Madeleine Lebeau...Madeleine, l'attrice francese Mary Indovino...La telepata Caterina Boratto...La signora misteriosa Frazier Rippy...Il segretario laico Eddra Gale...La Saraghina Francesco Rigamonti...Un'amico di Luisa Guido Alberti...Pace, il produttore Giulio Paradisi...Un'amico Mario Conocchia...Conocchia, il direttore di produzione Marco Gemini...Guido da ragazzo Bruno Agostini...Bruno - il secundo segretario di produzione Giuditta Rissone...La madre di Guido Cesarino Miceli Picardi...Cesarino, l'ispettore di produzione Annibale Ninchi...Il padre di Guido Jean Rougeul...Carini, il critico cinematografico Nino Rota...Bit Part Mario Pisu...Mario Mezzabotta Yvonne Casadei...Jacqueline Bonbon FEDERICO FELLINI -

Sculptors' Jewellery Offers an Experience of Sculpture at Quite the Opposite End of the Scale

SCULPTORS’ JEWELLERY PANGOLIN LONDON FOREWORD The gift of a piece of jewellery seems to have taken a special role in human ritual since Man’s earliest existence. In the most ancient of tombs, archaeologists invariably excavate metal or stone objects which seem to have been designed to be worn on the body. Despite the tiny scale of these precious objects, their ubiquity in all cultures would indicate that jewellery has always held great significance.Gold, silver, bronze, precious stone, ceramic and natural objects have been fashioned for millennia to decorate, embellish and adorn the human body. Jewellery has been worn as a signifier of prowess, status and wealth as well as a symbol of belonging or allegiance. Perhaps its most enduring function is as a token of love and it is mostly in this vein that a sculptor’s jewellery is made: a symbol of affection for a spouse, loved one or close friend. Over a period of several years, through trying my own hand at making rings, I have become aware of and fascinated by the jewellery of sculptors. This in turn has opened my eyes to the huge diversity of what are in effect, wearable, miniature sculptures. The materials used are generally precious in nature and the intimacy of being worn on the body marries well with the miniaturisation of form. For this exhibition Pangolin London has been fortunate in being able to collate a very special selection of works, ranging from the historical to the contemporary. To complement this, we have also actively commissioned a series of exciting new pieces from a broad spectrum of artists working today. -

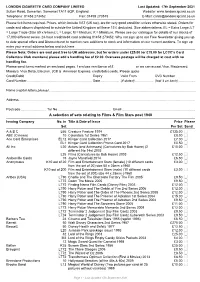

LCCC Thematic List

LONDON CIGARETTE CARD COMPANY LIMITED Last Updated: 17th September 2021 Sutton Road, Somerton, Somerset TA11 6QP, England. Website: www.londoncigcard.co.uk Telephone: 01458 273452 Fax: 01458 273515 E-Mail: [email protected] Please tick items required. Prices, which include VAT (UK tax), are for very good condition unless otherwise stated. Orders for cards and albums dispatched to outside the United Kingdom will have 15% deducted. Size abbreviations: EL = Extra Large; LT = Large Trade (Size 89 x 64mm); L = Large; M = Medium; K = Miniature. Please see our catalogue for details of our stocks of 17,000 different series. 24-hour credit/debit card ordering 01458 273452. Why not sign up to our Free Newsletter giving you up to date special offers and Discounts not to mention new additions to stock and information on our current auctions. To sign up enter your e-mail address below and tick here _____ Please Note: Orders are sent post free to UK addresses, but for orders under £25.00 (or £15.00 for LCCC's Card Collectors Club members) please add a handling fee of £2.00. Overseas postage will be charged at cost with no handling fee. Please send items marked on enclosed pages. I enclose remittance of £ or we can accept Visa, Mastercard, Maestro, Visa Delta, Electron, JCB & American Express, credit/debit cards. Please quote Credit/Debit Expiry Valid From CVC Number Card Number...................................................................... Date .................... (if stated).................... (last 3 on back) .................. Name -

50Annidolcevita.Compressed.Pdf

1 Questo volume nasce dal convegno “Mezzo secolo da La dolce vita”, tenuto a Rimini, al Teatro degli Atti, nei giorni 14 e 15 novembre 2008 Cura editoriale Giuseppe Ricci Traduzioni in inglese Robin Ambrosi Progetto grafico Lorenzo Osti, Mattia Di Leva per D-sign Fotografie Pierluigi (© Reporters Associati / Cineteca di Bologna) © 2009 Edizioni Cineteca di Bologna via Riva di Reno 72 40122 Bologna www.cinetecadibologna.it © 2009 Fondazione Federico Fellini via Nigra 26 47923 Rimini www.federicofellini.it 2 MEZZO SECOLO DI DOLCE VITA a cura di Vittorio Boarini e Tullio Kezich Texts in English and Italian 3 4 INDICE Tullio Kezich Testimone oculare 13 Eyewitness 17 Sergio Zavoli La dolce vita compie cinquant’anni 21 La dolce vita celebrates fifty years 27 Gianfranco Mingozzi Sul set con Fellini 33 On set with Fellini 41 Gianni Rondolino La dolce vita e il cinema degli anni sessanta 49 La dolce vita and the cinema of the sixties 57 Francesco Lombardi Il paesaggio sonoro della Dolce vita e le sue molteplici colonne sonore 65 The sound landscape of La dolce vita and its multiple soundtracks 71 John Francis Lane Fellini e il doppiaggio. L’amara fatica di doppiare in inglese La dolce vita 77 Fellini and dubbing. The bitter struggle to dub La dolce vita in English 83 Irene Bignardi La moda e il costume 89 Fashion and customs 93 Virgilio Fantuzzi L’atteggiamento della Chiesa nei confronti della Dolce vita 97 The Church’s position on La dolce vita 103 5 Maurizio Giammusso Il teatro negli anni della Dolce vita 109 Theatre during the Dolce vita years 113 Gino Zucchini Fellini “psicoanalista”? 117 Fellini a “psychoanalyst”? 123 Fabio Rossi La partitura acustica della Dolce vita. -

From 5 to 13 October at Fiere Di Parma

Press Release MERCANTEINFIERA AUTUMN THE POETRY OF THE HEEL, ITALIAN MASTERS OF PHOTOGRAPHY AND FOUR CENTURIES OF ART HISTORY From 5 to 13 October at Fiere di Parma Mercanteinfiera, the Fiere di Parma international exhibition of antiques, modern antiques, design and vintage collectibles, is an increasingly “fusion” event. Protagonists of the 38th edition are the Villa Foscarini Rossi Shoes Museum of the LVMH Group and the BDC Art Gallery in Parma, owned by Lucia Bonanni ad Mauro del Rio, curators of the two collateral exhibitions. On the one hand, stylists such as Dior, Kenzo, Yves Saint Laurent and Nicholas Kirkwood highlighted by the far-sightedness of the entrepreneur Luigino Rossi, the Muse- um’s founder. On the other, masters of the visual language such as Ghirri, Sottsass, Jodice, as well as the paparazzi. With Lino Nanni and Elio Sorci, we will dive into the years of the exuberant Dolce Vita. (Parma, 30 September 2019) - At the beginning there were” pianelle”, or “chopines”, worn by both aristocratic women and commoners to protect their feet from mud and dirt. They could be as high as 50 cm (but only for the richest ladies), while four centuries later Mari- lyn Monroe would build her image on a relatively very modest 11-cm peep toe heel. For Yves Saint Laurent the perfect stride required a 9-cm heel. This was too high for the Swinging Sixties of London and Twiggy, when ballerinas were the footwear of choice. Whether high, low, with a 9 or 11cm heel, shoes have always been the best-loved accesso- ry of fashion victims and many others and they are the protagonists of the collateral exhi- bition “In her Shoes. -

Tamar Presenta Yuri Sulle Orme Di Yuri Ahronovitch

TAMAR PRESENTA YURI SULLE ORME DI YURI AHRONOVITCH TVZI AVNI RUDOLF BUCHBINDER BORIS BELKIN CLAUDIO DESDERI NATALIA GUTMAN DAME GWYNETH JONES LEO NUCCI PAVEL KOGAN IGOR POLESITZKY un film di NEVIO CASADIO UFFICIO STAMPA [email protected] PHONE +491722160066 (GERMANIA) +97225661212 (ISRAELE) +972502169600 (WhatsApp) +393341097974 (ITALIA) TITOLO ORIGINALE: Yuri. Sulle orme di Yuri Ahronovitch LINGUA ORIGINALE: Italiano, Inglese, Tedesco, Russo, Ebraico PAESE DI PRODUZIONE: Israele, Italia ANNO: 2017 DURATA 126 minuti COLORE: Colore/Bianco e Nero AUDIO: Presa Diretta GENERE: Docufilm - Road Movie REGIA: Nevio Casadio SOGGETTO: Nevio Casadio, Tami Ahronovitch SCENEGGIATURA: Nevio Casadio PRODUTTORE: Tamar CASA DI PRODUZIONE DELEGATA: Bottega Video srl – Rimini PRODUTTORE ESECUTIVO: Francesco Cavalli FOTOGRAFIA: Marco Colonna, Diego Zicchetti, Roberto Bianchi MONTAGGIO: Nevio Casadio, Marco Colonna, OTTIMIZZAZIONE: Mirco Tenti ASSISTENTE DI PRODUZIONE: Melissa Manfredi CAST in ordine di apparizione nel ruolo di se stessi NEVIO CASADIO (REPORTER) Di professione giornalista, secondo le circostanze è definito: giornalista, reporter, scrittore, regista. Si considera un cacciatore o un narratore di storie. Sperando di poterle e saperle narrare. * LEO NUCCI (BARITONO) Nasce il 16 aprile del 1942 a Castiglione dei Pepoli, in provincia di Bologna. Dopo aver studiato nel capoluogo emiliano con Giuseppe Marchesi e Mario Bigazzi, si trasferisce a Milano per perfezionare la propria tecnica con l'aiuto di Ottavio Bizzarri. Nel 1967 esordisce nel "Barbiere di Siviglia" dii Gioacchino Rossini nel ruolo di Figaro, vincendo il concorso del Teatro lirico sperimentale di Spoleto. Si esibisce alla Scala di Milano il 30 gennaio del 1977, ancora una volta nella parte di Figaro. Si esibirà a Londra alla Royal Opera House (con "Luisa Miller", nel 1978), a New York al Metropolitan (con "Un ballo in maschera", nel 1980, al fianco di Luciano Pavarotti e a Parigi all'Opera.