FICTION WINTER 2020 SIXFOLD Fiction WINTER 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ysu1311869143.Pdf (795.38

THIS IS LIFE: A Love Story of Friendship by Annie Murray Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of M.F.A. in the NEOMFA Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY May, 2011 THIS IS LIFE: A Love Story of Friendship Annie Murray I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: ________________________________________________________ Annie Murray, Student Date Approvals: ________________________________________________________ David Giffels, Thesis Advisor Date ________________________________________________________ Phil Brady, Committee Member Date ________________________________________________________ Mary Biddinger, Committee Member Date ________________________________________________________ Peter J. Kasvinsky, Dean, School of Graduate Studies and Research Date © A. Murray 2011 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the universal journey of self discovery against the specific backdrop of the south coast of England where the narrator, an American woman in her early twenties, lives and works as a barmaid with her female travel companion. Aside from outlining the journey from outsider to insider within a particular cultural context, the thesis seeks to understand the implications of a defining friendship that ultimately fails, the ways a young life is shaped through travel and loss, and the sacrifices a person makes when choosing a place to call home. The thesis follows the narrator from her initial departure for England at the age of twenty-two through to her final return to Ohio at the age of twenty-seven, during which time the friendship with the travel companion is dissolved and the narrator becomes a wife and a mother. -

COVER TOPIC Eyewear Industry Grapples with E-Tailers' Impact

COVER TOPIC Brick & Click Eyewear Industry Grapples With E-Tailers’ Impact BY JOHN SAILER / SENIOR EDITOR when shopping for general retail goods, the practice own optical labs and sending their customers actual is still not as prevalent when consumers are shop- frames to try on before making their final selection. here’s no ignoring it. Internet retailing is ping for eyewear… Approximately 32 percent of This month’s Cover Story attempts to capture a an essential part of everyday life. It even people using the internet to assist in their last pur- panoramic screenshot of online optical retailing, T has its own day, CyberMonday, right at chase of eyewear actually made the purchase direct- from how traditional brick-and-mortar stores are the start of the holiday shopping season. Against ly online. By category: eyeglasses (2.4 percent), dipping their PD sticks into this tsunami of internet last year’s lingering economic uncertainty, 2011 OTC readers (3 percent), plano sunglasses (4.3 per- activity (“When Will Brick Add Click,” page 42) to proved that e-commerce is still growing. cent) and contact lenses (16.4 percent)… It is likely how online-only dispensers are addressing the “Throughout the year, growth rates versus the that close to 1.5 million to 1.7 million pairs of Rx needs of a customer who is also a patient with a prior year remained in double digits to significant- eyeglasses were purchased online during the unique prescription (“Online Retailers Talk Shop,” ly outpace growth at brick-and-mortar retail,” 12-month period ending December 2011.” page 44); from the latest Vision Council statistics according to comScore’s digital business analytics. -

Company Donation Description Value Art to Wear One of a Kind

Napa Humane's "Cause for the Paws" 2009 - Sunday, July 19, 2009 This is a sampling of Silent Auction lots accurately described as of July 17, 2009. All lots subject to change prior to the opening of bidding. Company Donation Description Value One of a kind "Sorceress" necklace of agate, sterling Art to Wear silver, and brown arenturine $300 Ballentine Vineyards 1 x 1.5L 2000 Estate Merlot $100 Beazley House B&B Inn One-night, midweek/non-holiday stay in our best room $368 Bikram Yoga Napa Valley Certificate for 5 Bikram Yoga classes $70 Zinsvalley Restaurant Gift certificate $75 Wine and cheese tasting for four at the Broman home (prior reservation required), plus 1 x 1.5L of 2003 Napa Broman Cellars Valley Cabernet Sauvignon $200 Cartons and Crates Gift certificate for Napa Valley Art Supplies $50 Cliff Lede Vineyards 6 x 750ml 2008 Napa Valley Sauvignon Blanc $264 Culinary Institute of America at Greystone Dinner for four guests $250 Debbie Ames Photography/Events Egret photo presented in 23 x 17 wood frame $425 Four one-day "Park Hopper" to Disneyland and Disney Disneyland Resort California Adventure Southern California theme parks $376 Small size doggie personal flotation device and Doggles, LLC matching Doggles sun protection $45 Eagle & Rose Estate 24 x 750ml Skyhawk Sauvignon Blanc $168 Far Niente sampler pack: 1 x 750ml 2007 Estate Bottled Oakville Chardonnay, 1 x 750ml 2006 Estate Bottled Oakville Cabernet Sauvignon, and 1 x 375 2005 Far Niente/Dolce Dolce $475 G.L. Mezzetta Inc. Gift basket $100 Grizzly Pet Products LLC Cello -

Women in Higher Education, 1997. ISSN ISSN-1060-8303 PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 200P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 418 623 HE 031 134 AUTHOR Wenniger, Mary Dee, Ed. TITLE Women in Higher Education, 1997. ISSN ISSN-1060-8303 PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 200p. AVAILABLE FROM Wenniger Company, 1934 Monroe St., Madison WI 53711-2027; phone: 608-251-3232; fax: 608-284-0601 (Annual subscription $79, U.S.; $89, Canada; $99 elsewhere). PUB TYPE Collected Works Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT Women in Higher Education; v6 n1-12 1997 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Administrators; College Administration; College Athletics; *College Faculty; College Students; *Females; Feminism; *Higher Education; Leadership; *Sex Discrimination; Womens Athletics; Womens Education ABSTRACT The 12 issues of this newsletter focus on issues concerned with women students, faculty, and administrators in higher education. Each issue includes feature articles, news items, and profiles of significant people. The issues' main articles address: women in athletics; leadership development for women; the first year in academic administration; strategies for campus feminists; women's attitudes in the class of 2000; progress at three universities in gender equity in athletics; gender differences in administrative salaries; using the World Wide Web; minority women; conflict over the new English curriculum at Georgetown University (District of Columbia); the mental health of women in math and science; job hunting; a sex bias suit against Ohio State University; 25 years after Title IX; sexuality and academic freedom; campus politics; reduction of date rape; women student -

Lu Liston Collection, B1989.016

REFERENCE CODE: AkAMH REPOSITORY NAME: Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center Bob and Evangeline Atwood Alaska Resource Center 625 C Street Anchorage, AK 99501 Phone: 907-929-9235 Fax: 907-929-9233 Email: [email protected] Guide prepared by: Sara Piasecki, Archivist; Tim Remick, contractor; and Haley Jones, Museum volunteer TITLE: Lu Liston Collection COLLECTION NUMBER: B1989.016 OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION Dates: circa 1899-1967 Extent: 21 linear feet Language and Scripts: The collection is in English. Name of creator(s): The following list includes photographers identified on negatives or prints in the collection, but is probably not a complete list of all photographers whose work is included in the collection: Alaska Shop Bornholdt Robert Bragaw Nellie Brown E. Call Guy F. Cameron Basil Clemons Lee Considine Morris Cramer Don Cutter Joseph S. Dixon William R. Dahms Julius Fritschen George Dale Roy Gilley Glass H. W. Griffin Ted Hershey Denny C. Hewitt Eve Hamilton Sidney Hamilton E. A. Hegg George L. Johnson Johnson & Tyler R. C. L. Larss & Duclos Sydney Laurence George Lingo Lucien Liston William E. Logemann Lomen Bros. Steve McCutcheon George Nelson Rossman F. S. Andrew Simons H. W. Steward Thomas Kodagraph Shop Marcus V. Tyler H. A. W. Bradford Washburn Ward Wells Frank Wright Jr. Administrative/Biographical History: Lucien Liston was a longtime Alaskan businessman and artist, and has been described as the last of a long line of drug store photographers who provided images for sale to the traveling public. He was born in 1910 in Eugene, Oregon, and came to Alaska in 1929, living first in Juneau, where he met and married Edna Reindeau. -

Tourist Trap: on Being Raised in Award-Winning Sand

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2007 Tourist Trap: On Being Raised In Award-winning Sand Catherine Jane Carson University of Central Florida Part of the Creative Writing Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Carson, Catherine Jane, "Tourist Trap: On Being Raised In Award-winning Sand" (2007). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 3109. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/3109 TOURIST TRAP: ON BEING RAISED IN AWARD-WINNING SAND by CATHERINE J. CARSON B.A. University of Central Florida, 2005 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Department of English in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2007 ABSTRACT The literary essays in this collection explore the relationships between mind, body, and environment as the narrator explores Orlando, her beachfront hometown of Sarasota, and other “tourist traps.” The vignettes and traditional and experimental essays here question how residents make popular vacation destinations their own, how newcomers establish themselves as part of local culture, and how much trust one can put in strangers and neighbors, from theme- park designers to lovers. Dance floors, hybrid bikes, flying elephants, swing sets, and swimming pools fill these pages. -

MILLE TINDRESSE Madeleine Stack

MILLE TINDRESSE Madeleine Stack some women walk down the street thinking they own the world and o I wish it were true I want queerness as twinned desiring and identifying I want headphones clamped to head, tights straining at that ass, want a common architecture of elegant ruin, glowing velveteen. I want coats this season in dun, taupe, milk, sand, camouflaging ourselves in a landscape we have yet to understand. I want the hole in my jumper to stay but not get any bigger. Want the problem’s beauty but not its further unraveling and eventual devastation. I want clickbait, The Color That Makes Everything Look More Expensive I want that to clothe oneself is to become visible-invisible simultaneously. But to be seen as what. I want WHAT R U WEARING RN BABE I want to know how to we make ourselves read, how do we make ourselves understood by others. I want to be to have and to hold Attending to what women wear in the street. Here I try to be a woman in the world taught wanting. Want a long red skirt and a red sweater. I want a grey streak in black hair I want christening-lace edging a blouse. I want holes in my shoes. I want a belly and a backpack. I want yellow eyeglasses. I want an amulet swinging a snake tattoo sneakers braids. I want a box pleat, white jeans, a tiny rope at my wrist black velvet bow in my hair. how do you frame your desire are you in the gallery or the pit Want wet hair flat moving flat like lace across neck, ball gag, flip flops, suede cravat. -

University of Alberta (Canada)

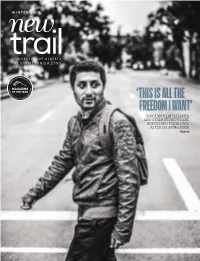

WINTER 2017 UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA ALUMNI MAGAZINE ‘THIS IS ALL THE FREEDOM I WANT’ HOW ABDULLAH ALTAMER AND OTHER STUDENTS ARE REBUILDING THEIR LIVES AFTER ESCAPING SYRIA Page 26 WINTER 2017 ON THE COVER VOLUME 73 NUMBER 3 Even the act of walking to school is meaningful to Abdullah Altamer, one of 14 Syrian students who have come to the U of A through the President’s Award for Refugees and Displaced Persons. Page 26 Photo by John Ulan “ The littlest thing tripped me up in more ways than one.” Whatever life brings your way, small or big, departments take advantage of a range of insurance options 3 at preferential group rates. Your Letters 5 Getting coverage for life-changing events may seem like a Notes What’s new and noteworthy given to some of us. But small things can mean big changes 12 too. Like an unexpected interruption to your income. Alumni Continuing Education insurance plans can have you covered at every stage of life, Column by Curtis Gillespie every step of the way. 16 Whatsoever Things Are True You’ll enjoy affordable rates on Term Life Insurance, Column by Todd Babiak Major Accident Protection, Income Protection Disability, 17 Health & Dental Insurance and others. The protection Thesis There are answers that you need. The competitive rates you want. lie at the intersection of words and images. 43 Get a quote today. Call 1-888-913-6333 or visit us Trails Where you’ve been and at manulife.com/uAlberta. where you’re going 44 features Books 26 46 Seen / Unseen Class Notes After fleeing conflict, three Syrian students embrace 59 the everyday moments. -

THE VIRTUOSO and the TRUTH LIES ELSEWHERE: an Encounter with the Past Through a Reading of W.G. Sebald's AUSTERLITZ a Creative P

THE VIRTUOSO and THE TRUTH LIES ELSEWHERE: An Encounter with the Past through a Reading of W.G. Sebald's AUSTERLITZ A creative project (novel) and exegesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sonia Orchard BA BAppSc (Hons) School of Creative Media Portfolio of Design and Social Context RMIT University January 2007 Declaration I certify that: • except where due acknowledgement is made, all work submitted is my own; • the work has not been submitted previously, in whole or in part, to qualify for any other academic award; • the content of this doctorate is the result of work which has been carried out since the official commencement date of the approved research program; • any editorial work, paid or unpaid, carried out by a third party is acknowledged. Signed Sonia Orchard, January 2007 11 Acknowledgments This project would not have been possible without the support and assistance of many people and organisations. This research has been partially funded through a Commonwealth Government Australian Postgraduate Award. In June-July 2003, I spent 8 weeks in London researching for the novel. I am extremely grateful to all those who agreed to be interviewed about Noel Mewton-Wood: Dr John Amis, John Dalby, Dr Patrick Trevor-Roper, Lady Pauline Del Mar, Margaret Kitchin, Tim Gordon, Bryce Morrison and Denys Gurvault. In addition, John Amis gave me access to his collection ofMewton-Wood concert programmes and was of enormous assistance during my stay in London. I would also like to acknowledge the following British organisations and institutions, and their very helpful staff: the British Library (including the British Sound Archives), the British National Archives, the BBC Written Archives, the Britten-Pears Library, the Lambeth Archives, the National Gallery (Archives dept), the British Music Information Centre, the English National Opera, Wigmore Hall, the Royal Albert Hall, the Royal Festival Hall, the Royal College of Music and the Royal Academy of Music. -

Laser Protection for Medical Applications

31 Laser protection for medical applications uvex-laservision.de Table of contents 4 Manufacturing expertise uvex safety + uvex sports. 13 Contents: Frames One brand. One mission. 14 Overspecs 16 Specials 18 Sporty frames 24 Laser protection filters for medical industries 25 Dental applications 30 Dermatological applications 36 Surgical applications 41 Cleaning and disinfection 43 IPL applications 46 Anti-splash eyewear 48 Patient protection protecting people 54 Veterinary medicine As part of the uvex group, we commit ourselves to the uvex quality promise with 56 Large-area laser protection the best possible care and responsibility. For us, “protecting people” means not only 60 Webshop information compliance with norms and standards, but to meet also the expectations of customers regarding services, processes and latest 63 Medical professional enquiry form product technologies. The know-how transfer between laservision, uvex safety and uvex sports makes our products even safer, more functional and more comfortable. Printing errors: All specifications, Norms and descriptions are subject to change without notice. Copyright: All rights reserved. Texts, images, graphics are subject to copyright and other protective laws. The content of this publication may not be copied, distributed or modified for commercial purposes without written authorisation by LASERVISION GmbH & Co. KG. 2 Thank you for your interest in laservision laser protection products. The protection of people from artificial optical radiation is the focus of our daily work empha- sized since mid-2018 by our new claim “protecting people”, which on the one hand takes into account the expansion of our laser protection product range in the direction of laser safety cabins and system solutions and on the other hand makes our membership of the uvex safety group even more clear. -

Antiques, Collectibles, Furniture and More in Smiths Grove Ky

09/28/21 04:06:58 Antiques, Collectibles, Furniture and more in Smiths Grove Ky Auction Opens: Mon, Aug 2 4:37pm CT Auction Closes: Mon, Aug 9 6:05pm CT Lot Title Lot Title 1866 1930's Wooden Howdy Doody Doll 1894 Vintage Starter Pistol Made In Italy 1867 Putnam Lightning Amber Canning Jar 1895 Antique L&N Railroad Brass Lock 1868 Supee Mario Sunshine Nintendo Gamecube 1896 Lot Of Antique Keys Game 1897 Antique Shaving Lot 1869 Pauline's Hard Cover Book By Pauline Tabor 1898 Lot Of Vintage Safety Razors 1870 Nintendo Game Cube With Controller 1899 Lot Of Vintage Shaving Brushes In Cigar Box 1871 Super Mario Bros. Color Screen Game & Watch 1900 Lot Of Antique Straight Razors Some With 1872 Paperboy Super Nintendo Game Issues 1873 Super Mario All-Stars Super Nintendo Game 1901 Vintage SR Cast Iron Skillet 1874 Super Mario Odyssey Nintendo Switch Game 1902 Cast Iron Skillet 1875 Super Mario Bros. U Deluxe Nintendo Switch 1903 Antique Cast Iron Griswold Skillet # 5 Game 1904 Antique Cast Iron Skillet No. 5 1876 Lot Of 3 Nintendo Switch Games 1905 Cast Iron Skillet No 5 1877 Lot Of 3 Nintendo Switch Games 1906 Antique Cast Iron Skillet 1878 Lot Of 3 Nintendo Switch Games 1907 Antique Bham Stove And Range Co. Cast Iron 1879 Vintage Remington Temperature Gauge Skillet Mini 1880 Vintage 1960's NOS Gum Ball Machine 1908 Antique Cast Iron Skillet No. 6 1881 Vintage Hess Delivery Truck In Box 1909 Antique Cast Iron Skillet 1882 Lot Of 6 Wheat Pennies 3 Indian Head 1910 Antique Cast Iron Skillet No 8 1883 1907 D Barber Half Dollar 1911 Antique Cast Iron Wagner Skillet 1884 1976 Ike Dollar 1912 Antique Wagner Cast Iron Skillet 1885 1916 D Barber Quarter 1913 Antique Cast Iron Skillet No. -

Epistemology Dana Kathleen Woolley Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2012 Epistemology Dana Kathleen Woolley Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Fine Arts Commons Recommended Citation Woolley, Dana Kathleen, "Epistemology" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 12521. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/12521 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Epistemology by Dana Kathleen Woolley A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS Major: Creative Writing and Environment Program of Study Committee: David Zimmerman, Major Professor Christiana Langenberg Clay Pierce Greg Wilson Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2012 Copyright © Dana Kathleen Woolley, 2012. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract iii Hydrology 1 Toxicology 22 Ichthyology 46 Ornithology 66 Cryptozoology 83 Genealogy 101 Biographical Sketch 127 iii ABSTRACT The following is a collection of six short works of fiction. Each story contains at least one protagonist who grapples with some sort of ethical decision related in part to science or natural resource management. The story titles reflect the type of study and quest for knowledge each protagonist goes through. This collection contains elements of scientific influence, humor, and magical realism in combination to reflect a world very similar, but slightly off-kilter, to the one the reader inhabits.