Waltz with Bashir 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beneath the Surface *Animals and Their Digs Conversation Group

FOR ADULTS FOR ADULTS FOR ADULTS August 2013 • Northport-East Northport Public Library • August 2013 Northport Arts Coalition Northport High School Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Courtyard Concert EMERGENCY Volunteer Fair presents Jazz for a Yearbooks Wanted GALLERY EXHIBIT 1 Registration begins for 2 3 Friday, September 27 Children’s Programs The Library has an archive of yearbooks available Northport Gallery: from August 12-24 Summer Evening 4:00-7:00 p.m. Friday Movies for Adults Hurricane Preparedness for viewing. There are a few years that are not represent- *Teen Book Swap Volunteers *Kaplan SAT/ACT Combo Test (N) Wednesday, August 14, 7:00 p.m. Northport Library “Automobiles in Water” by George Ellis Registration begins for Health ed and some books have been damaged over the years. (EN) 10:45 am (N) 9:30 am The Northport Arts Coalition, and Safety Northport artist George Ellis specializes Insurance Counseling on 8/13 Have you wanted to share your time If you have a NHS yearbook that you would like to 42 Admission in cooperation with the Library, is in watercolor paintings of classic cars with an Look for the Library table Book Swap (EN) 11 am (EN) Thursday, August 15, 7:00 p.m. and talents as a volunteer but don’t know where donate to the Library, where it will be held in posterity, (EN) Friday, August 2, 1:30 p.m. (EN) Friday, August 16, 1:30 p.m. Shake, Rattle, and Read Saturday Afternoon proud to present its 11th Annual Jazz for emphasis on sports cars of the 1950s and 1960s, In conjunction with the Suffolk County Office of to start? Visit the Library’s Volunteer Fair and speak our Reference Department would love to hear from you. -

Screening Trauma in Waltz with Bashir and Lebanon

Anna Ball 1 ‘Looking the Beast in the Eye’: Screening Trauma in Waltz With Bashir and Lebanon Published in The Ethics of Representation in Literature, Art and Journalism: Transnational Responses to the Siege of Beirut, ed. Caroline Rooney and Rita Sakr (London: Routledge, 2013), pp.71-85. PRE-PRINT PROOF: PLEASE REFER TO PRINTED VERSION FOR CITATION Anna Ball, [email protected] Having looked the beast of the past in the eye, having asked and received forgiveness and made amends, let us shut the door on the past – not in order to forget it but in order not to allow it to imprison us. - Archbishop Desmond Tutu, South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report.i [Figure 1: Image from Waltz With Bashir, dir. Ari Folman (London: Artificial Eye, 2008).] It is the kind of place that we have all visited in our dreams: somewhere that at first seems drearily familiar, a nocturnal cityscape perhaps, streets littered and rain-sodden. Until you see the sky. Not black but a lurid yellow: a sickly light, the colour of phosphorous, an unnatural illumination of the darkness. Then, as you knew they would, they come, all twenty-six of them, snarling and slathering, sleek black coats gleaming in the rain, eyes bright as flares. All Anna Ball 2 night, they circle beneath your window, howl at you through your restless sleep, and though in the morning they will be gone, as dreams always are, you know that they will return – for this is what it is to be hunted by this particular kind of beast. -

2021 International Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust

Glasses of those murdered at Auschwitz Birkenau Nazi German concentration and death camp (1941-1945). © Paweł Sawicki, Auschwitz Memorial 2021 INTERNATIONAL DAY OF COMMEMORATION IN MEMORY OF THE VICTIMS OF THE HOLOCAUST Programme WEDNESDAY, 27 JANUARY 2021 11:00 A.M.–1:00 P.M. EST 17:00–19:00 CET COMMEMORATION CEREMONY Ms. Melissa FLEMING Under-Secretary-General for Global Communications MASTER OF CEREMONIES Mr. António GUTERRES United Nations Secretary-General H.E. Mr. Volkan BOZKIR President of the 75th session of the United Nations General Assembly Ms. Audrey AZOULAY Director-General of UNESCO Ms. Sarah NEMTANU and Ms. Deborah NEMTANU Violinists | “Sorrow” by Béla Bartók (1945-1981), performed from the crypt of the Mémorial de la Shoah, Paris. H.E. Ms. Angela MERKEL Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany KEYNOTE SPEAKER Hon. Irwin COTLER Special Envoy on Preserving Holocaust Remembrance and Combatting Antisemitism, Canada H.E. Mr. Gilad MENASHE ERDAN Permanent Representative of Israel to the United Nations H.E. Mr. Richard M. MILLS, Jr. Acting Representative of the United States to the United Nations Recitation of Memorial Prayers Cantor JULIA CADRAIN, Central Synagogue in New York El Male Rachamim and Kaddish Dr. Irene BUTTER and Ms. Shireen NASSAR Holocaust Survivor and Granddaughter in conversation with Ms. Clarissa WARD CNN’s Chief International Correspondent 2 Respondents to the question, “Why do you feel that learning about the Holocaust is important, and why should future generations know about it?” Mr. Piotr CYWINSKI, Poland Mr. Mark MASEKO, Zambia Professor Debórah DWORK, United States Professor Salah AL JABERY, Iraq Professor Yehuda BAUER, Israel Ms. -

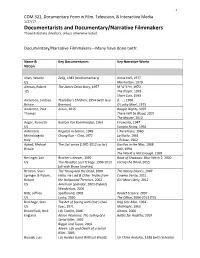

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film, Television, & Interactive Media 1/27/17 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anderson, Paul Junun, 2015 Boogie Nights, 1997 Thomas There Will be Blood, 2007 The Master, 2012 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Antonioni, Ragazze in bianco, 1949 L’Avventura, 1960 Michelangelo Chung Kuo – Cina, 1972 La Notte, 1961 Italy L'Eclisse, 1962 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Berlinger, Joe Brother’s Keeper, 1992 Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, 2000 US The Paradise Lost Trilogy, 1996-2011 Facing the Wind, 2015 (all with Bruce Sinofsky) Berman, Shari The Young and the Dead, 2000 The Nanny Diaries, 2007 Springer & Pulcini, Hello, He Lied & Other Truths from Cinema Verite, 2011 Robert the Hollywood Trenches, 2002 Girl Most Likely, 2012 US American Splendor, 2003 (hybrid) Wanderlust, 2006 Blitz, Jeffrey Spellbound, 2002 Rocket Science, 2007 US Lucky, 2010 The Office, 2006-2013 (TV) Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, -

War and Peace on Film Political Science 229: Special Topics in International Relations the College of Wooster Spring 2010

Appendix: Lantis Class Syllabus War and Peace on Film Political Science 229: Special Topics in International Relations The College of Wooster Spring 2010 Dr. Jeffrey Lantis Office Hours: Kauke 107, #2408 MT 3:30-4:30 pm Course Description “War” and “Peace” are two of the most important topics in the study of international relations. Many believe that these conditions are inextricably linked—that we truly cannot understand one without the other. This course will explore classic and contemporary issues in international peace and security through the media of film, literature, and scholarly works. Key sections of the class examine the origins of war, international terrorism, just-war theory, peace studies, and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. More broadly, we critically analyze issues central to human nature including conflict and harmony, wartime experiences, questions of heroism and glory, national identity and conceptions of the “other” through films and popular writings. This course will prompt students to not only examine their own assumptions about historical narratives of peace and security but also to recognize the symbiotic relationship between popular culture and international relations. Course Objectives This is an advanced class. It is expected that you have had prior coursework in the discipline or related areas of study. The class is designed as a seminar where we will critically analyze concepts in international peace and security. Educational objectives for this class include to: • provide a strong foundation in modern studies of peace and security; • re-examine assumptions and explore critical questions regarding the root causes of war and peace; • place theories in international security and peace studies in a meaningful context; • better understand the origins of peace and conflict through the means of alternative pedagogies; • strengthen research, writing, and analytical skills. -

LEVY-MASTERSREPORT-2017.Pdf (7.541Mb)

Copyright by Dylan Olim Levy 2017 The Report Committee for Dylan Olim Levy Certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: Animating History and Memory: the Productions and Aesthetics of Waltz with Bashir and Tower APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Lalitha Gopalan Charles Ramìrez Berg Animating History and Memory: the Productions and Aesthetics of Waltz with Bashir and Tower by Dylan Olim Levy, B.A. Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2017 Abstract Animating History and Memory: the Productions and Aesthetics of Waltz with Bashir and Tower Dylan Olim Levy, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2017 Supervisor: Lalitha Gopalan Films like Waltz with Bashir (2008) and Tower (2016) are unique in that they not only fit within accepted frameworks of documentary filmmaking, but they also use animation as their primary method of storytelling. Anabelle Honess Roe thoroughly explores animated documentaries in her book Animated Documentary, arguing that animation is used in these kinds of films to either “substitute” for traditional means to represent the real world (24), such as live action footage, or to “evoke” the psychology, emotional states, and other subjective experiences of an individual (25). Ultimately, Roe argues that animation is a suitable “representational strategy for documentary” filmmaking because of its “visual dialectic of absence and excess” (39). This report applies Roe’s arguments to the analysis of the aesthetics and roles of animation in Waltz with Bashir and Tower. -

THE SWALLOWS of KABUL for the Strength of Its Subject and Its Artistic Impetus

1 ARTISTERY on display... ...fans of adult theme animation will seek the film out (Screen International) Graphically RICH...dramatically and poetically RIGHT (Variety) This film threads an UNDYING HOPE for the future through every shade of its tragedy and sacrifice (Roger Ebert.com) VISUALLY arresting and emotionally engaging (Eye for Film) 2 Engaging and captivating (Cinefilos) Not to be missed (Taxidrivers) A VISUAL cinematic POEM (EFE Agency) Ultimately TOUCHING...BEAUTIFUL watercolor-like animation (Film Companion) An animated JEWEL (RTVE) If animation can, through the lightness of the drawing line and touches of color, evoke the intimate and the universal while revealing the forbidden, then we want to reward THE SWALLOWS OF KABUL for the strength of its subject and its artistic impetus. (DOMINIQUE HOFF, GENERAL DELEGATE OF THE GAN FOUNDATION) 3 PRESS COVERAGE 4 5 May 16th, 2019 Alissa Simon, Cannes Film Review: ‘The Swallows of KABUL’ Two female directors co-sign this involving adaptation of Yasmina Khadra’s elegant literary fiction ABOUT life UNDER Taliban control in the Afghan capital. The long-awaited, graphically rich, 2D watercolor-style animation “The Swallows Of Kabul” from French helmers Zabou Breitman and Eléa Gobbé-Mévellec provides an involving adaptation of Yasmina Khadra’s elegant literary fiction. The book, an international bestseller about life under Taliban control in the Afghan capital, highlighted a dangerous act of humanity during a grim and violent time via the stories of two couples whose fates become intertwined through death, imprisonment, and remarkable self-sacrifice. This supplies the core plot of the film, with the action condensed into a tight 81 minutes. -

A Hybrid Documentary Genre: Animated Documentary and the Analysis of Waltz with Bashir (2008) Movie Barış Tolga Ekinci, [email protected]

A hybrid documentary genre: Animated documentary and the analysis of Waltz with Bashir (2008) movie Barış Tolga Ekinci, [email protected] Volume 6.1 (2017) | ISSN 2158-8724 (online) | DOI 10.5195/cinej.2017.144 | http://cinej.pitt.edu Abstract The word documentary has been described as an advice in “Oxford English Dictionary” in the late 1800s. Document is a main source of information for lawyers. And in cinema, basic film forms are defined with their own properties. The common sense is to seperate documentary from fiction, experimental from main current and animation from the live action films. While these definitions were being made, it has been considered that which expression methods were used. The film genre which is called documentary has been defined in many different ways. In this study, animated documentary genre which is a form of hybrid documentary has been concerned with Baudrillard’s theory. In this context, Ari Folman’s animated documentary Waltz with Bassir (2008) has been analyzed with genre criticism method. Keywords: Documentary, animated documentary, Waltz with Bassir, reality, hybrid genres. New articles in this journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 United States License. This journal is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press. A Hybrid documentary genre: Animated documentary and the analysis of Waltz with Bashir (2008) movie Barış Tolga Ekinci Introduction History of animated documentary1 is old as much as history of traditional documentary. However, in any period, animated documentaries have not been reached the popularity of traditional documentaries. -

Everyday Transcendence: Contemporary Art Film and the Return to Right Now

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations January 2019 Everyday Transcendence: Contemporary Art Film And The Return To Right Now Aaron Pellerin Wayne State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pellerin, Aaron, "Everyday Transcendence: Contemporary Art Film And The Return To Right Now" (2019). Wayne State University Dissertations. 2333. https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations/2333 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. EVERYDAY TRANSCENDENCE: CONTEMPORARY ART FILM AND THE RETURN TO RIGHT NOW by AARON PELLERIN DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2019 MAJOR: ENGLISH (Film and Media Studies) Approved By: _________________________________________ Advisor Date _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY AARON PELLERIN 2019 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION For Sue, who always sees the magic in the everyday. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I‘d like to thank my committee, and in particular my advisor, Dr. Steve Shaviro. His encouragement, his insightful critiques, and his early advice to just write were all instrumental in making this work what it is. I likewise wish to thank Dr. Scott Richmond for the time and energy he put in as I struggled through the middle stages of the degree. I am also grateful for a series of challenging and exciting seminars I took with Steve, Scott, and also with Dr. -

Eine Abendfüllende Therapie Für Den Trickfilm

Eine abendfüllende Therapie für den Trickfilm Was der abendfüllende Animationsfilm zu leisten imstande ist – neue Möglichkeiten der Erzählung am Beispiel von „Waltz with Bashir“ und „Persepolis“ Betreuer: Prof. Frank Gessner Jost Althoff weiterer Gutachter: Konrad Weise Studiengang Animation Hochschule für Film und Matrikel Nummer 4308 Fernsehen „Konrad Wolf“ 2010 Abbildung 1 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis Einleitung ................................................................................................................ 4 These................................................................................................................... 6 Anamnese:....................................................................................................... 6 Therapie........................................................................................................... 7 Diagnose.......................................................................................................... 8 Begriffsklärung ........................................................................................................ 8 Was ist eine Autobiografie?................................................................................. 8 Der Wirklichkeitsbezug im Film........................................................................ 9 Der selbstreflexive Bezug im Film.................................................................. 10 Der abendfüllende Trickfilm ........................................................................... 13 Filmbesprechung.................................................................................................. -

Exploring Trauma Through Fantasy

IN-BETWEEN WORLDS: EXPLORING TRAUMA THROUGH FANTASY Amber Leigh Francine Shields A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2018 Full metadata for this thesis is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this thesis: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/16004 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4 Abstract While fantasy as a genre is often dismissed as frivolous and inappropriate, it is highly relevant in representing and working through trauma. The fantasy genre presents spectators with images of the unsettled and unresolved, taking them on a journey through a world in which the familiar is rendered unfamiliar. It positions itself as an in-between, while the consequential disturbance of recognized world orders lends this genre to relating stories of trauma themselves characterized by hauntings, disputed memories, and irresolution. Through an examination of films from around the world and their depictions of individual and collective traumas through the fantastic, this thesis outlines how fantasy succeeds in representing and challenging histories of violence, silence, and irresolution. Further, it also examines how the genre itself is transformed in relating stories that are not yet resolved. While analysing the modes in which the fantasy genre mediates and intercedes trauma narratives, this research contributes to a wider recognition of an understudied and underestimated genre, as well as to discourses on how trauma is narrated and negotiated. -

A.I. Artifical Intelligence About a Boy Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter

A.I. Artifical Intelligence Almost Holy The Art of Racing in the Rain About A Boy Aloha The Artist Abraham Lincoln: Alone in Berlin Vampire Hunter As Time Goes By: The Already Tomorrow in Complete Series Abyss Hong Kong Atomic Blonde Across the Universe Amelie Atonement Ad Astra American Assassin Au Revoir Les Enfants Adam's Rib American Gods: Season 1 The Autobiography of Miss Adaptation The Americans: Seasons 1- Jane Pittman 3 After the Wedding Avatar The American Side The Aftermath Away from Her American Sniper The Age of Adaline Baby Driver Amistad Albert Nobbs Back to the Future II An American in Paris Alien Balzac and the Little Anatomy of a Murder Chinese Seamstress Alien:Covenant And the Band Played On Band of Brothers Alien 3 And Then There Were Bandits Alien Resurrection None The Band's Visit Aliens Angel Has Fallen Bang the Drum Slowly All About Eve Angels in America Barefoot Contessa All Creatures Great and Annie Hall Small Battlestar Galactica: Anywhere But Here Seasons 1-4.5 All My Friends Are Funeral Singers The Apartment Beast All of My Heart: Inn Love Approaching the Unknown Beatriz At Dinner All of My Heart: The Apocalypse Now A Beautiful Day in the Wedding Neighborhood Apollo 13 All the Money in the World Because I Said So Argo All the President's Men Becoming Jane Arn: The Knight Templar Before I Fall Black Hawk Down Bridesmaids Before Midnight Black or White Brigadoon Before Sunrise Black Panther Bridge of Spies Before Sunset Black Swan The Bridge on the River Kwai Being 17 Blade Runner Brightburn Bella Blade Runner