AJS Review Cinema Studies/Jewish Studies, 2011–2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles University, Faculty of Arts East and Central European Studies

Charles University, Faculty of Arts East and Central European Studies Summer 2016 Jewish Images in Central European Cinema CUFA F 380 Instructor: Kevin Johnson Email: [email protected] Office Hours: by appointment Classes: Mon + Tue, 12.00 – 3.15, Wed 12.00 – 2.45, H201 (Hybernská 3, Prague 1) Course Description This course examines the portrayal of Jews and Jewish themes in the cinemas of Central Europe from the 1920s until the present. It considers not only depictions of Jews made by gentiles (sometimes with anti-Semitic undertones), but also looks at productions made by Jewish filmmakers aimed at a primarily Jewish audience. The selection of films is representative of the broader region where Czech, Slovak, Polish, Hungarian, Ruthenian, Ukranian, German, and Yiddish are (or were historically) spoken. Although attention will be given to the national-political context in which the films were made, most of the films by their very nature defy easy classification according to strict categories of statehood—this is particularly true for the pre-World War II Yiddish-language films. For this reason, the films will also be examined with an eye toward broader, transnational connections and global networks of people and ideas. Primary emphasis will be placed on two areas: (1) films that depict and document pre-Holocaust Jewish society in Central Europe, and (2) post-War films that seek to come terms with the Holocaust and the nearly absolute destruction of Jewish culture and tradition in the region. Weekly film screenings will be supplemented by theoretical readings related to the films or to concepts associated with them. -

Beneath the Surface *Animals and Their Digs Conversation Group

FOR ADULTS FOR ADULTS FOR ADULTS August 2013 • Northport-East Northport Public Library • August 2013 Northport Arts Coalition Northport High School Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Courtyard Concert EMERGENCY Volunteer Fair presents Jazz for a Yearbooks Wanted GALLERY EXHIBIT 1 Registration begins for 2 3 Friday, September 27 Children’s Programs The Library has an archive of yearbooks available Northport Gallery: from August 12-24 Summer Evening 4:00-7:00 p.m. Friday Movies for Adults Hurricane Preparedness for viewing. There are a few years that are not represent- *Teen Book Swap Volunteers *Kaplan SAT/ACT Combo Test (N) Wednesday, August 14, 7:00 p.m. Northport Library “Automobiles in Water” by George Ellis Registration begins for Health ed and some books have been damaged over the years. (EN) 10:45 am (N) 9:30 am The Northport Arts Coalition, and Safety Northport artist George Ellis specializes Insurance Counseling on 8/13 Have you wanted to share your time If you have a NHS yearbook that you would like to 42 Admission in cooperation with the Library, is in watercolor paintings of classic cars with an Look for the Library table Book Swap (EN) 11 am (EN) Thursday, August 15, 7:00 p.m. and talents as a volunteer but don’t know where donate to the Library, where it will be held in posterity, (EN) Friday, August 2, 1:30 p.m. (EN) Friday, August 16, 1:30 p.m. Shake, Rattle, and Read Saturday Afternoon proud to present its 11th Annual Jazz for emphasis on sports cars of the 1950s and 1960s, In conjunction with the Suffolk County Office of to start? Visit the Library’s Volunteer Fair and speak our Reference Department would love to hear from you. -

Screening Trauma in Waltz with Bashir and Lebanon

Anna Ball 1 ‘Looking the Beast in the Eye’: Screening Trauma in Waltz With Bashir and Lebanon Published in The Ethics of Representation in Literature, Art and Journalism: Transnational Responses to the Siege of Beirut, ed. Caroline Rooney and Rita Sakr (London: Routledge, 2013), pp.71-85. PRE-PRINT PROOF: PLEASE REFER TO PRINTED VERSION FOR CITATION Anna Ball, [email protected] Having looked the beast of the past in the eye, having asked and received forgiveness and made amends, let us shut the door on the past – not in order to forget it but in order not to allow it to imprison us. - Archbishop Desmond Tutu, South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report.i [Figure 1: Image from Waltz With Bashir, dir. Ari Folman (London: Artificial Eye, 2008).] It is the kind of place that we have all visited in our dreams: somewhere that at first seems drearily familiar, a nocturnal cityscape perhaps, streets littered and rain-sodden. Until you see the sky. Not black but a lurid yellow: a sickly light, the colour of phosphorous, an unnatural illumination of the darkness. Then, as you knew they would, they come, all twenty-six of them, snarling and slathering, sleek black coats gleaming in the rain, eyes bright as flares. All Anna Ball 2 night, they circle beneath your window, howl at you through your restless sleep, and though in the morning they will be gone, as dreams always are, you know that they will return – for this is what it is to be hunted by this particular kind of beast. -

2021 International Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust

Glasses of those murdered at Auschwitz Birkenau Nazi German concentration and death camp (1941-1945). © Paweł Sawicki, Auschwitz Memorial 2021 INTERNATIONAL DAY OF COMMEMORATION IN MEMORY OF THE VICTIMS OF THE HOLOCAUST Programme WEDNESDAY, 27 JANUARY 2021 11:00 A.M.–1:00 P.M. EST 17:00–19:00 CET COMMEMORATION CEREMONY Ms. Melissa FLEMING Under-Secretary-General for Global Communications MASTER OF CEREMONIES Mr. António GUTERRES United Nations Secretary-General H.E. Mr. Volkan BOZKIR President of the 75th session of the United Nations General Assembly Ms. Audrey AZOULAY Director-General of UNESCO Ms. Sarah NEMTANU and Ms. Deborah NEMTANU Violinists | “Sorrow” by Béla Bartók (1945-1981), performed from the crypt of the Mémorial de la Shoah, Paris. H.E. Ms. Angela MERKEL Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany KEYNOTE SPEAKER Hon. Irwin COTLER Special Envoy on Preserving Holocaust Remembrance and Combatting Antisemitism, Canada H.E. Mr. Gilad MENASHE ERDAN Permanent Representative of Israel to the United Nations H.E. Mr. Richard M. MILLS, Jr. Acting Representative of the United States to the United Nations Recitation of Memorial Prayers Cantor JULIA CADRAIN, Central Synagogue in New York El Male Rachamim and Kaddish Dr. Irene BUTTER and Ms. Shireen NASSAR Holocaust Survivor and Granddaughter in conversation with Ms. Clarissa WARD CNN’s Chief International Correspondent 2 Respondents to the question, “Why do you feel that learning about the Holocaust is important, and why should future generations know about it?” Mr. Piotr CYWINSKI, Poland Mr. Mark MASEKO, Zambia Professor Debórah DWORK, United States Professor Salah AL JABERY, Iraq Professor Yehuda BAUER, Israel Ms. -

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film, Television, & Interactive Media 1/27/17 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anderson, Paul Junun, 2015 Boogie Nights, 1997 Thomas There Will be Blood, 2007 The Master, 2012 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Antonioni, Ragazze in bianco, 1949 L’Avventura, 1960 Michelangelo Chung Kuo – Cina, 1972 La Notte, 1961 Italy L'Eclisse, 1962 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Berlinger, Joe Brother’s Keeper, 1992 Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, 2000 US The Paradise Lost Trilogy, 1996-2011 Facing the Wind, 2015 (all with Bruce Sinofsky) Berman, Shari The Young and the Dead, 2000 The Nanny Diaries, 2007 Springer & Pulcini, Hello, He Lied & Other Truths from Cinema Verite, 2011 Robert the Hollywood Trenches, 2002 Girl Most Likely, 2012 US American Splendor, 2003 (hybrid) Wanderlust, 2006 Blitz, Jeffrey Spellbound, 2002 Rocket Science, 2007 US Lucky, 2010 The Office, 2006-2013 (TV) Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, -

War and Peace on Film Political Science 229: Special Topics in International Relations the College of Wooster Spring 2010

Appendix: Lantis Class Syllabus War and Peace on Film Political Science 229: Special Topics in International Relations The College of Wooster Spring 2010 Dr. Jeffrey Lantis Office Hours: Kauke 107, #2408 MT 3:30-4:30 pm Course Description “War” and “Peace” are two of the most important topics in the study of international relations. Many believe that these conditions are inextricably linked—that we truly cannot understand one without the other. This course will explore classic and contemporary issues in international peace and security through the media of film, literature, and scholarly works. Key sections of the class examine the origins of war, international terrorism, just-war theory, peace studies, and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. More broadly, we critically analyze issues central to human nature including conflict and harmony, wartime experiences, questions of heroism and glory, national identity and conceptions of the “other” through films and popular writings. This course will prompt students to not only examine their own assumptions about historical narratives of peace and security but also to recognize the symbiotic relationship between popular culture and international relations. Course Objectives This is an advanced class. It is expected that you have had prior coursework in the discipline or related areas of study. The class is designed as a seminar where we will critically analyze concepts in international peace and security. Educational objectives for this class include to: • provide a strong foundation in modern studies of peace and security; • re-examine assumptions and explore critical questions regarding the root causes of war and peace; • place theories in international security and peace studies in a meaningful context; • better understand the origins of peace and conflict through the means of alternative pedagogies; • strengthen research, writing, and analytical skills. -

LEVY-MASTERSREPORT-2017.Pdf (7.541Mb)

Copyright by Dylan Olim Levy 2017 The Report Committee for Dylan Olim Levy Certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: Animating History and Memory: the Productions and Aesthetics of Waltz with Bashir and Tower APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Lalitha Gopalan Charles Ramìrez Berg Animating History and Memory: the Productions and Aesthetics of Waltz with Bashir and Tower by Dylan Olim Levy, B.A. Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2017 Abstract Animating History and Memory: the Productions and Aesthetics of Waltz with Bashir and Tower Dylan Olim Levy, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2017 Supervisor: Lalitha Gopalan Films like Waltz with Bashir (2008) and Tower (2016) are unique in that they not only fit within accepted frameworks of documentary filmmaking, but they also use animation as their primary method of storytelling. Anabelle Honess Roe thoroughly explores animated documentaries in her book Animated Documentary, arguing that animation is used in these kinds of films to either “substitute” for traditional means to represent the real world (24), such as live action footage, or to “evoke” the psychology, emotional states, and other subjective experiences of an individual (25). Ultimately, Roe argues that animation is a suitable “representational strategy for documentary” filmmaking because of its “visual dialectic of absence and excess” (39). This report applies Roe’s arguments to the analysis of the aesthetics and roles of animation in Waltz with Bashir and Tower. -

THE SWALLOWS of KABUL for the Strength of Its Subject and Its Artistic Impetus

1 ARTISTERY on display... ...fans of adult theme animation will seek the film out (Screen International) Graphically RICH...dramatically and poetically RIGHT (Variety) This film threads an UNDYING HOPE for the future through every shade of its tragedy and sacrifice (Roger Ebert.com) VISUALLY arresting and emotionally engaging (Eye for Film) 2 Engaging and captivating (Cinefilos) Not to be missed (Taxidrivers) A VISUAL cinematic POEM (EFE Agency) Ultimately TOUCHING...BEAUTIFUL watercolor-like animation (Film Companion) An animated JEWEL (RTVE) If animation can, through the lightness of the drawing line and touches of color, evoke the intimate and the universal while revealing the forbidden, then we want to reward THE SWALLOWS OF KABUL for the strength of its subject and its artistic impetus. (DOMINIQUE HOFF, GENERAL DELEGATE OF THE GAN FOUNDATION) 3 PRESS COVERAGE 4 5 May 16th, 2019 Alissa Simon, Cannes Film Review: ‘The Swallows of KABUL’ Two female directors co-sign this involving adaptation of Yasmina Khadra’s elegant literary fiction ABOUT life UNDER Taliban control in the Afghan capital. The long-awaited, graphically rich, 2D watercolor-style animation “The Swallows Of Kabul” from French helmers Zabou Breitman and Eléa Gobbé-Mévellec provides an involving adaptation of Yasmina Khadra’s elegant literary fiction. The book, an international bestseller about life under Taliban control in the Afghan capital, highlighted a dangerous act of humanity during a grim and violent time via the stories of two couples whose fates become intertwined through death, imprisonment, and remarkable self-sacrifice. This supplies the core plot of the film, with the action condensed into a tight 81 minutes. -

A Hybrid Documentary Genre: Animated Documentary and the Analysis of Waltz with Bashir (2008) Movie Barış Tolga Ekinci, [email protected]

A hybrid documentary genre: Animated documentary and the analysis of Waltz with Bashir (2008) movie Barış Tolga Ekinci, [email protected] Volume 6.1 (2017) | ISSN 2158-8724 (online) | DOI 10.5195/cinej.2017.144 | http://cinej.pitt.edu Abstract The word documentary has been described as an advice in “Oxford English Dictionary” in the late 1800s. Document is a main source of information for lawyers. And in cinema, basic film forms are defined with their own properties. The common sense is to seperate documentary from fiction, experimental from main current and animation from the live action films. While these definitions were being made, it has been considered that which expression methods were used. The film genre which is called documentary has been defined in many different ways. In this study, animated documentary genre which is a form of hybrid documentary has been concerned with Baudrillard’s theory. In this context, Ari Folman’s animated documentary Waltz with Bassir (2008) has been analyzed with genre criticism method. Keywords: Documentary, animated documentary, Waltz with Bassir, reality, hybrid genres. New articles in this journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 United States License. This journal is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press. A Hybrid documentary genre: Animated documentary and the analysis of Waltz with Bashir (2008) movie Barış Tolga Ekinci Introduction History of animated documentary1 is old as much as history of traditional documentary. However, in any period, animated documentaries have not been reached the popularity of traditional documentaries. -

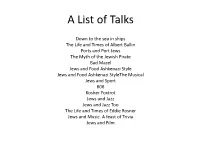

A List of Talks

A List of Talks Down to the sea in ships The Life and Times of Albert Ballin Ports and Port Jews The Myth of the Jewish Pirate Bad Mazel Jews and Food Ashkenazi Style Jews and Food Ashkenazi StyleThe Musical Jews and Sport 606 Kosher Foxtrot Jews and Jazz Jews and Jazz Too The Life and Times of Eddie Rosner Jews and Music. A feast of Trivia Jews and Film PORTS AND PORT JEWS The Port City was the gateway to settlement for Jews on their many migrations. Sometimes they stayed and settled, often they moved on to the hinterland. Before the advent of the aeroplane Port Cities were vital for the continuance of Jewish life. They enabled multi-continental networks to be set up, as well as providing a place of refuge and an escape hatch. Many of the places have now faded in our collective memory, but remain a vibrant part of the history of the last 2000 years. Tony will show you how those Port Jews adapted, survived, and even flourished. Including • The merchants of antiquity • The Atlantic triangle • Port Jews – Hull and Charleston • Odessa and Trieste – the Free Ports • City of Mud and Jews • The fishermen of Salonika - and Haifa • The last Port Jews The Myth of the Jewish Pirate Over the past few years an industry has grown up around the myth of the Jewish Pirate. There has been an exhibition in Marseille; a book called Jewish Pirates of the Caribbean; there are guided tours in Jamaica, and Jewish speakers regularly give talks on the subject. -

YIDDISH FILM BETWEEN TWO WORLDS DATES November 14, 1991 - January 9, 1992

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release May 1991 FACT SHEET EXHIBITION YIDDISH FILM BETWEEN TWO WORLDS DATES November 14, 1991 - January 9, 1992 ORGANIZATION Adrienne Mancia, Curator, Department of Film, The Museum of Modern Art; Sharon Pucker Rivo, Executive Director, The National Center for Jewish Film, located at Brandeis University; and J. Hoberman, author and film critic, The Village Voice. SPONSOR Supported by a grant from The Nathan Cummings Foundation. Funding for the accompanying publication was provided by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. The gallery exhibition is made possible by the Rita J. and Stanley H. Kaplan Foundation in memory of Gladys and Saul Gwirtzman. CONTENT This first major retrospective of Yiddish cinema comprises films made in the United States and Europe from the 1920s through the 1980s. The exhibition includes melodramas, farces, tragedies, musical comedies, and documentaries that capture the talents of such international stars as Ida Kaminska, Lila Lee, Solomon Mikhoels, Molly Picon, and Maurice Schwartz. While only a fragment of the once vibrant world of Yiddish theater and cinema survives, these films depict the concerns and values of Yiddish culture and preserve the nuances of the Yiddish language. Chronicling the struggle for Jewish identity on both sides of the Atlantic, the exhibition features Yiddle with His Fiddle (1936) and The Dybbuk (1937), from Poland; Jewish Luck (1925) and The Return of Nathan Beck (1934), from Russia; East and Hest (1923), from Austria; and Uncle Moses (1932), Tevye (1939), and God, Man, and Devil (1950), from the United States. Several recent films, including Brussels Transit (1980), from Belgium, and If They Give, Take (1983), from Israel, offer a contemporary glimpse of Yiddish-language drama. -

Everyday Transcendence: Contemporary Art Film and the Return to Right Now

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations January 2019 Everyday Transcendence: Contemporary Art Film And The Return To Right Now Aaron Pellerin Wayne State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pellerin, Aaron, "Everyday Transcendence: Contemporary Art Film And The Return To Right Now" (2019). Wayne State University Dissertations. 2333. https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations/2333 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. EVERYDAY TRANSCENDENCE: CONTEMPORARY ART FILM AND THE RETURN TO RIGHT NOW by AARON PELLERIN DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2019 MAJOR: ENGLISH (Film and Media Studies) Approved By: _________________________________________ Advisor Date _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY AARON PELLERIN 2019 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION For Sue, who always sees the magic in the everyday. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I‘d like to thank my committee, and in particular my advisor, Dr. Steve Shaviro. His encouragement, his insightful critiques, and his early advice to just write were all instrumental in making this work what it is. I likewise wish to thank Dr. Scott Richmond for the time and energy he put in as I struggled through the middle stages of the degree. I am also grateful for a series of challenging and exciting seminars I took with Steve, Scott, and also with Dr.