Fishermen's Cooperatives in Kerala: a Critique – BOBP/MIS/01

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Design for Component A

Consultancy Services for Implementation of Component-A of Last Mile Connectivity of NCRMP TECHNICAL DESIGN REPORT Version: 2.0 Credit # 4772-IN Submitted by: Telecommunications Consultants India Limited TCIL Bhawan, Greater Kailash Part – I New Delhi- 110 048, India. TECHNICAL DESIGN REPORT TCIL Document Details Project Title Consultancy Services for Implementation of Component-A of Last Mile Connectivity of National Cyclone Risk Mitigation Project (NCRMP) Report Title Technical Design Report Report Version Version 2.0 Client State Project Implementation Unit (SPIU) National Cyclone Risk Mitigation Project - Kerala (NCRMP- Kerala) Department of Disaster Management Government of Kerala Report Prepared by Project Team Date of Submission 19.12.2018 TCIL’s Point of Contact Mr. A. Sampath Kumar Team Leader Telecommunications Consultants India Limited TCIL Bhawan, Greater Kailash-I New Delhi-110048 [email protected] Private & Confidential Page 2 TECHNICAL DESIGN REPORT TCIL Contents List of Abbreviations ..................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................... 9 2. EARLY WARNING DISSEMINATION SYSTEM .......................................................................................... 9 3. Objective of the Project ..................................................................................................................... -

Case Study2 Niche Tourism Marketing

IIUM Journal of Case Studies in Management: Vol. 1: 23-35, 2010 ISSN 2180-2327 Case Study2 Niche Tourism Marketing Manoj Edward Cochin University of Science and Technology, India Babu P George* University of Southern Mississippi, USA Abstract: This case study focuses on a niche tourism operator in Kerala, India, offering tour packages mainly in the areas of adventure and ecotourism. The operation began in 2000, and by 2008 had achieved considerable growth mainly due to the owners’ steadfast commitment and passionate approach to the product idea being promoted. Over the years, the firm has witnessed many changes in terms of modifying the initial idea of the product to suit market realities such as adding new services and packages, expanding to new markets, and starting of new ventures in related areas. In the process, the owners have faced various challenges and tackled most them as part of pursuing sustained growth. The present case study aims to capture these growth dynamics specific to entrepreneurship challenges. Specific problems in the growth stage like issues in designing an innovative niche product and delivering it with superior quality, coordinating with an array of suppliers, and tapping international tourism markets with a limited marketing budget, are explored in this study. Also, this study explores certain unique characteristics of the firm’s operation which has a bearing on the niche area it operates. Lastly, some of the critical issues pertaining to entrepreneurship in the light of the firm’s future growth plans are also outlined. INTRODUCTION Kalypso Adventures is a package tour company that was started in 2000 by two Naval Commanders of the Indian Navy, Cdr. -

Most Rev. Dr. M. Soosa Pakiam L.S.S.S., Thl. Metropolitan Archbishop of Trivandrum

LATIN ARCHDIOCESE OF TRIVANDRUM His Grace, Most Rev. Dr. M. Soosa Pakiam L.S.S.S., Thl. Metropolitan Archbishop of Trivandrum Date of Birth : 11.03.1946 Date of Ordination : 20.12.1969 Date of Episcopal Ordination : 02.02.1990 Metropolitan Archbishop of Trivandrum: 17.06.2004 Latin Archbishop's House Vellayambalam, P.B. No. 805 Trivandrum, Kerala, India - 695 003 Phone : 0471 / 2724001 Fax : 0471 / 2725001 E-mail : [email protected] Website : www.latinarchdiocesetrivandrum.org 1 His Excellency, Most Rev. Dr. Christudas Rajappan Auxiliary Bishop of Trivandrum Date of Birth : 25.11.1971 Date of Ordination : 25.11.1998 Date of Episcopal Ordination : 03.04.2016 Latin Archbishop's House Vellayambalam, P.B. No. 805 Trivandrum, Kerala, India - 695 003 Phone : 0471 / 2724001 Fax : 0471 / 2725001 Mobile : 8281012253, 8714238874, E-mail : [email protected] [email protected] Website : www.latinarchdiocesetrivandrum.org (Dates below the address are Dates of Birth (B) and Ordination (O)) 2 1. Very Rev. Msgr. Dr. C. Joseph, B.D., D.C.L. Vicar General & Chancellor PRO & Spokesperson Latin Archbishop's House, Vellayambalam, Trivandrum - 695 003, Kerala, India T: 0471-2724001; Fax: 0471-2725001; Mobile: 9868100304 Email: [email protected], [email protected] B: 14.04.1949 / O: 22.12.1973 2. Very Rev. Fr. Jose G., MCL Judicial Vicar, Metropolitan Archdiocesan Tribunal & Chairman, Archdiocesan Arbitration and Conciliation Forum Latin Archbishop's House, Vellayambalam, Trivandrum T: 0471-2724001; Fax: 0471-2725001 & Parish Priest, St. Theresa of Lisieux Church, Archbishop's House Compound, Vellayambalam, Trivandrum - 695 003 T: 0471-2314060 , Office ; 0471-2315060 ; C: 0471- 2316734 Web: www.vellayambalamparish.org Mobile: 9446747887 Email: [email protected] B: 06.06.1969 / O: 07.01.1998 3. -

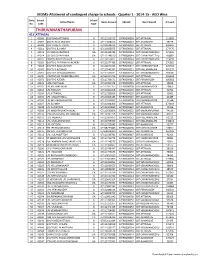

MDMS-Allotment of Contingent Charge to Schools - Quarter 1 - 2014-15 - AEO Wise

MDMS-Allotment of contingent charge to schools - Quarter 1 - 2014-15 - AEO Wise Code School School School Name Bank Account IFSCode Bank Branch Amount No. Code Type THIRUVANANTHAPURAM 423 ATTINGAL 1 42006 GOVT.BHS ATTINGAL G 67111616552 SBTR0000039 SBT ATTINGAL 111803 2 42007 GOVT.HSS ALAMCODE G 67111858456 SBTR0000667 SBT ALAMCODE 59229 3 42008 GOVT.GHS ATTINGAL G 67132614276 SBTR0000039 SBT ATTINGAL 229187 4 42011 GOVT.HS ELAMBA G 67112505555 SBTR0000039 SBT ATTINGAL 277475 5 42013 SCV BHS CHIRAYINKIL GA 67112428239 SBTR0000044 SBT CHIRAYINKEEZHU 121616 6 42014 SSV GHS CHIRAYINKIL GA 67112248610 SBTR0000044 SBT CHIRAYINKEEZHU 168092 7 42015 PNM HS KOONTHALLOR G 67112150011 SBTR0000044 SBT CHIRAYINKEEZHU 112033 8 42021 GOVT.HS AVANANAVANCHERY G 67112377485 SBTR0000039 SBT ATTINGAL 270581 9 42023 GOVT.HS KAVALAYOOR G 67112070463 SBTR0000347 SBT CHERUNNIYOOR 126703 10 42035 GOVT.HS NJEKKAD G 67110542395 SBTR0000221 SBT KALLAMBALAM 365137 11 42051 GOVT.HS VENJARAMOODU G 67111635031 SBTR0000254 SBT VENJARAMOODU 268785 12 42070 JANATHA HS THEMPAMOODU GA 67152191276 SBTR0000039 SBT ATTINGAL 255358 13 42072 GOVT.HS AZOOR G 67111735171 SBTR0000312 SBT PERUNGUZHI 185082 14 42301 LMSLPSATINGAL GA 67110367478 SBTR0000039 SBT ATTINGAL 39819 15 42302 LPS.KEEZHATINGAL G 67111917377 SBTR0000038 SBT KADAKKAVOOR 20863 16 42303 LPS ANDOOR G 67110960208 SBTR0000039 SBT ATTINGAL 30799 17 42304 LPS.ATTINGAL G 67111955856 SBTR0000039 SBT ATTINGAL 21851 18 42305 LPS. MELATTINGAL G 67110464483 SBTR0000667 SBT ALAMCODE 41489 19 42306 LPS MELKADAKKAVOOR G 67110742837 SBTR0000038 SBT KADAKKAVOOR 31548 20 42307 LPS.ELAMBA G 67111864469 SBTR0000039 SBT ATTINGAL 173914 21 42308 LPS ALAMCODE G 67112200869 SBTR0000667 SBT ALAMCODE 41356 22 42309 LPS MADATHUVATHUKKAL G 67110530809 SBTR0000052 SBT VAMANAPURAM 74110 23 42310 PTM LPS KUMPALATHUMPARA GA 67112281715 SBTR0000052 SBT VAMANAPURAM 42812 24 42311 .LPS. -

Download Socio-Economic Survey of Kovalam Forane

SOCIO-ECONOMIC AND PASTORAL SURVEY A REPORT AND ANALYSIS KOVALAM FORANE LATIN ARCHDIOCESE OF TRIVANDRUM Vellayambalam, Trivandrum Vol. 6 KOVALAM FORANE 1 SOCIO-ECONOMIC AND PASTORAL SURVEY 2011 A REPORT AND ANALYSIS KOVALAM FORANE Latin Archdiocese of Trivandrum, Vellayambalam Data Collection and Data Entry BCC & TSSS (Archdiocese of Trivandrum) Software Development Mr. Justus S. Data Analysis and Survey Report Dr. J. Mary John ADHWANA Resource Center, Thiruvananthapuram +91 944 797 1846 Design and Layout SKETCH +91 77 3650 2049 sketchtricks.com Survey Team Msgr. James Culas J. Fr. Sabbas Ignatius G.N. Fr. Edison Y.M. (Coordinator) Published by Latin Archdiocese of Trivandrum Archbishop’s House Compound Samanwaya, Vellayambalam Thiruvananthapuram - 3 © TSSS & BCC 2013, May 2 TRIVANDRUM LATIN ARCHDIOCESE. PLATINUM JUBILEE SURVEY-2011 Contents Preface 5 Foreward 7 Map 9 Archdiocesan History 11 Forane History 15 List of Chart 21 List of Table 23 Chapter1 27 Introduction and Methodology Chapter 2 33 Presentation of Data Chapter 3 93 Summary of Findings and Recommendations Annexure Annexure 1: Tables 103 Annexure 2: Schedule 247 KOVALAM FORANE 3 4 TRIVANDRUM LATIN ARCHDIOCESE. PLATINUM JUBILEE SURVEY-2011 Preface History always recalls National Census as one of the greatest achievements of any ruler who accomplishes it, precisely because it presupposes vision, systematic planning and sincere dream for sustainable development of his or her kingdom. 2012 was a milestone in the annals of the Latin Archdiocese of Trivandrum which celebrated its Platinum Jubilee that year. One of the important events which added colour and grandeur and substance was the socio-economic, pastoral and civic survey of the Archdiocesan population. -

A Tryst with Siffs in Kerala by Debashish Maitra and Kushankur

A Tryst With Siffs in Kerala 4 Debashish Maitra and Kushankur Dey CASE STUDY This umbrella organisation of fishermen’s societies has demonstrated how a marketing-based platform, if well managed, can reap rich dividends for traditional, small-scale artisinal livelihoods. The origin of the South Indian Federation of Fishermen Societies (SIFFS) network, that works in the Marine Fisheries sector, dates back to the Seventies. A diocesan rehabilitation project resettled fish workers from various localities in an uninhabited stretch of coast, later christened Marianad, about 20 km north of Trivandrum, the capital of the state of Kerala. One of the major problems that the fish workers faced in the new settlement was that of marketing their fish catch. The marketing system of the region at that time involved beach auctions. Controlled by merchants and middlemen, the system was inherently exploitative. Confronted with this, the fish workers with the assistance of a team of social workers decided to set up their own marketing system and appointed their own auctioneer. Faced with a determined set of fish workers, the merchants, who till then controlled the business, eventually had to yield. The fishing community then took over a dormant cooperative society that had been registered in the village earlier and started operations formally. This was the first fish marketing society called Marianad Matsya Utpadaka Cooperative Society (MUCS). The society was member-based and marketing-oriented, with membership open only to active fish workers who managed the society themselves. The three core activities of MUCS were marketing of fish caught by members, providing credit for renewal of fishing equipment and promoting savings. -

Physical Geography of Edava - Nadayara and Paravur Backwaters, Kerala, India

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN: 2319-7064 ResearchGate Impact Factor (2018): 0.28 | SJIF (2019): 7.583 Physical Geography of Edava - Nadayara and Paravur Backwaters, Kerala, India Haritha .Y .A1, Dr. Jayalekshmi .V .K2 1Research Scholar, Department of Geography, University College, Thiruvananthapuram-695034, India 2Assistant Professor, Department of Geography, University College, Thiruvananthapuram-695034, India Abstract: Water is the important phenomenon that differentiates the Earth from other members in the Milky Way. Besides being the prominent life sustaining component in the ecosystem, water plays a versatile role in the functioning of the bio-geo-chemical cycles. A backwater means the network of interconnected lakes and they were formed by the actions of shore currents and sea waves constructing low depressions at the mouth of rivers. The backwaters of Kerala are located where the freshwater from rivers meet Lakshadweep Sea in the west. Man has been using the backwaters for ages for fishing, transportation, agriculture and other related activities. Edava- Nadayara and Paravur backwaters lies between Lakshadweep Sea and Western Ghats in the south-western part of Kerala, India and is well known for their scenic beauty. Ithikkara river is the main feeder of Paravur lake and Ayiroor River, which is the second smallest river in Kerala finally emptying into the Edava- Nadayara lake. The backwater system has a total area of 101.026 sq. kms including the lakes which covers 10.325 sq. kms. The main objective of this study is to analyse the physical settings and characteristics of Edava- Nadayara and Paravur backwaters by inventorying the geomorphology, geology, climate, soil, slope, flora and fauna with the help of primary and secondary data sources. -

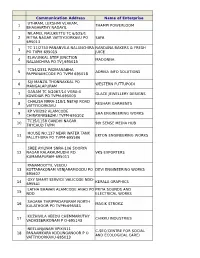

Communication Address Name of Enterprise 1 THAMPI

Communication Address Name of Enterprise UTHRAM, LEKSHMI VLAKAM, 1 THAMPI POWERLOOM BHAGAVATHY NADAYIL NILAMEL NALUKETTU TC 6/525/1 2 MITRA NAGAR VATTIYOORKAVU PO SAFA 695013 TC 11/2750 PANANVILA NALANCHIRA NANDANA BAKERS & FRESH 3 PO TVPM 695015 JUICE ELAVUNKAL STEP JUNCTION 4 MADONNA NALANCHIRA PO TV[,695015 TC54/2331 PADMANABHA 5 ADRIKA INFO SOLUTIONS PAPPANAMCODE PO TVPM 695018 SIJI MANZIL THONNAKKAL PO 6 WESTERN PUTTUPODI MANGALAPURAM GANAM TC 5/2067/14 VGRA-4 7 GLACE JEWELLERY DESIGNS KOWDIAR PO TVPM-695003 CHALISA NRRA-118/1 NETAJI ROAD 8 RESHAM GARMENTS VATTIYOORKAVU KP VIII/292 ALAMCODE 9 SHA ENGINEERING WORKS CHIRAYINKEEZHU TVPM-695102 TC15/1158 GANDHI NAGAR 10 9th SENSE MEDIA HUB THYCAUD TVPM HOUSE NO.137 NEAR WATER TANK 11 EKTON ENGINEERING WORKS PALLITHURA PO TVPM-695586 SREE AYILYAM SNRA-106 SOORYA 12 NAGAR KALAKAUMUDHI RD. VKS EXPORTERS KUMARAPURAM-695011 PANAMOOTTIL VEEDU 13 KOTTARAKONAM VENJARAMOODU PO DEVI ENGINEERING WORKS 695607 OXY SMART SERVICE VALICODE NDD- 14 KERALA GRAPHICS 695541 LATHA BHAVAN ALAMCODE ANAD PO PRIYA SOUNDS AND 15 NDD ELECTRICAL WORKS SAGARA THRIPPADAPURAM NORTH 16 MAGIK STROKZ KULATHOOR PO TVPM-695583 KUZHIVILA VEEDU CHEMMARUTHY 17 CHIKKU INDUSTRIES VADASSERIKONAM P O-695143 NEELANJANAM VPIX/511 C-SEC(CENTRE FOR SOCIAL 18 PANAAMKARA KODUNGANOOR P O AND ECOLOGICAL CARE) VATTIYOORKAVU-695013 ZENITH COTTAGE CHATHANPARA GURUPRASADAM READYMADE 19 THOTTAKKADU PO PIN695605 GARMENTS KARTHIKA VP 9/669 20 KODUNGANOORPO KULASEKHARAM GEETHAM 695013 SHAMLA MANZIL ARUKIL, 21 KUNNUMPURAM KUTTICHAL PO- N A R FLOUR MILLS 695574 RENVIL APARTMENTS TC1/1517 22 NAVARANGAM LANE MEDICAL VIJU ENTERPRISE COLLEGE PO NIKUNJAM, KRA-94,KEDARAM CORGENTZ INFOTECH PRIVATE 23 NAGAR,PATTOM PO, TRIVANDRUM LIMITED KALLUVELIL HOUSE KANDAMTHITTA 24 AMALA AYURVEDIC PHARMA PANTHA PO TVM PUTHEN PURACKAL KP IV/450-C 25 NEAR AL-UTHMAN SCHOOL AARC METAL AND WOOD MENAMKULAM TVPM KINAVU HOUSE TC 18/913 (4) 26 KALYANI DRESS WORLD ARAMADA PO TVPM THAZHE VILAYIL VEEDU OPP. -

TSSS Annual Report 2018 – 2019

REGISTERED IN 1960, UNDER THE T.C. LITERARY, SCIENTIFIC AND CHARITABLE SOCIETIES REGISTRATION ACT OF XII, 1955, REG. NO. 352/85 TSSS GOLDEN JUBILEE BUILDING ARCHBISHOP’S HOUSE COMPOUND, VELLAYAMBALAM THIRUVANANTHAPURAM- 695003 1 TSSS Annual Report 2018 – 2019 Editorial Team Patrons & Trustee Most Rev. Dr. Soosa Pakiam M. Rt. Rev. Dr. Christudas R. Managing Editor Rev. Fr. Sabbas Ignatius G.N. Chief Editor Mr. Thomas Thekkel Editorial Board Rev. Fr. Ashlin Jose Rev. Fr. John Dall Mrs. Jismy Jose Mrs. Sherly V.S. Design & layout Mrs. Sherly V.S. Trivandrum Socal Service Society Vellayambalam Trivandrum – 3 21-02-2020 2 MESSAGE FROM THE TRUSTEE I am pleased that our Social Action Ministry is functioning very well and through the Social Service Society we could address the current challenges of the society. The society’s participatory roles of activities have aroused the hidden talents and dormant commitments of many men and women for the benefit of the community and the society at large. The different programmes and projects to make the individual, family and the society liquor/drug free, the shelter project even to those who have no land, the health programmes - both preventive care and support - including the differently abled, caring individual family and their needs through Save A Family Programme, child care and protection programme, women empowerment programmes and skill development and income generation, caring the orphans and mentally retarded, job and skill trainings through the institutions, and reaching the needy of calamities and disasters, linkages with GOs and NGOs for the betterment of different kinds of labourers and Pravasies were very active during the year under report. -

Cultural Heritage of Kerala

BOOKS DC Prof. A. Sreedhara Menon Born on December 18, 1925 at Eranakulam. Completed his M. A. Degree in History as a private candidate from the University of Madras with first rank in 1948. Went to Harvard University on a Fullbright Travel Grant and a Smith- Mund Scholarship and secured Masters degree in Political Science from there with specialisation in International Relations. Worked in various capacities such as Professor of History, State Editor of the Kerala Gazetteers, Registrar of the University of Kerala and UGC visiting Professor in the University of Calicut. Held many other positions during his eventful career. Apart from compiling eight District Gazetteers of Kerala he has written more than 25 books in English and Malayalam. BOOKS DC 1 Cultural Heritage of Kerala Other books in English by A. Sreedhara Menon from D C Books Kerala and Freedom Struggle A Survey of Kerala History BOOKS DC 2 A. Sreedhara Menon Cultural Heritage of Kerala BOOKS DC B D C Books 3 English Language Cultural Heritage of Kerala History by A. Sreedhara Menon © D C Books/Rights Reserved First Published in 1978 First e-book edition November 2010 Cover Design Priyaranjanlal Publishers D C Books, Kottayam 686 001 Kerala State, India website : www.dcbooks.com e-mail : [email protected] Although utmost care has been taken in the preparation of this book, neither the publishers nor the editors/compilers can accept any liability for any consequence arising from the information contained therein. The publisher will be grateful for any information, which will assist them in keeping future editions up to date. -

Draft Industrial Potential Survey

DRAFT INDUSTRIAL POTENTIAL SURVEY DISTRICT :THIRUVANANTHAPURAM Introduction Thiruvananthapuram District is the southernmost district of the coastal state of Kerala, in south India. It came into existence in the year 1957. The headquarters is the city of Thiruvananthapuram (Trivandrum) which is also the capital city of Kerala. Thiruvananthapuram city and several other places in the district loom large in ancient tradition, folklore and literature. In 1684, during the regency of Umayamma Rani, the English East India Company obtained a sandy spit of land at Anchuthengu near Varkala on the sea coast about 32 kilometres (20 mi) north of Thiruvananthapuram city, with a view to erecting a factory and fortifying it. The place had earlier been frequented by the Portuguese and later by the Dutch. It was from here that the English gradually extended their domain to other parts of Travancore. Modern history begins with Marthanda Varma, 1729 CE – 1758 CE, who is generally regarded as the Father of modern Travancore. Thiruvananthapuram was known as a great centre of intellectual and artistic activities in those days. "Thiruvananthapuram" literally means "City of Lord Anantha". The name derives from the deity of the Hindu temple at the center of the Thiruvananthapuram city. Anantha is the mythical thousand hooded serpent- Shesha on whom Padmanabhan or Vishnu reclines. The temple of Vishnu reclining on Anantha, the Sri Padmanabhaswamy temple, which dates back to the 16th century, is the most-recognizable iconic landmark of the city as well as the district. Along with the presiding deity of SriPadmanabha, this temple also has temples inside it, dedicated to Lord Krishna and Lord Narasimha, Lord Ganesha, and Lord Ayyappa. -

Non-Iconic Movements of Tradition in Keralite Classical Dance Justine Lemos

Document generated on 09/26/2021 10:09 p.m. Recherches sémiotiques Semiotic Inquiry Radical Recreation: Non-Iconic Movements of Tradition in Keralite Classical Dance Justine Lemos Recherches anthropologiques Article abstract Anthropological Inquiries Many studies assume that dance develops as a bearer of tradition through Volume 32, Number 1-2-3, 2012 iconic continuity (Downey 2005; Hahn 2007; Meduri 1996, 2004; Srinivasan 2007, 2011, Zarrilli 2000). In some such studies, lapses in Iconic continuity are URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1027772ar highlighted to demonstrate how “tradition” is “constructed”, lacking DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1027772ar substantive historical character or continuity (Meduri 1996; Srinivasan 2007, 2012). In the case of Mohiniyattam – a classical dance of Kerala, India – understanding the form’s tradition as built on Iconic transfers of semiotic See table of contents content does not account for the overarching trajectory of the forms’ history. Iconic replication of the form as it passed from teacher to student was largely absent in its recreation in the early 20th century. Simply, there were very few Publisher(s) dancers available to teach the older practice to new dancers in the 1960s. And yet, Mohiniyattam dance is certainly considered to be a “traditional” style to its Association canadienne de sémiotique / Canadian Semiotic Association practitioners. Throughout this paper I argue that the use of Peircean categories to understand the semiotic processes of Mohiniyattam’s reinvention in the 20th ISSN century allows us to reconsider tradition as a matter of Iconic continuity. In 0229-8651 (print) particular, an examination of transfers of repertoire in the early 20th century 1923-9920 (digital) demonstrates that the “traditional” and “authentic” character of this dance style resides in semeiotic processes beyond Iconic reiteration; specifically, the “traditional” character of Mohiniyattam is Indexical and Symbolic in nature.