A Tryst with Siffs in Kerala by Debashish Maitra and Kushankur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Design for Component A

Consultancy Services for Implementation of Component-A of Last Mile Connectivity of NCRMP TECHNICAL DESIGN REPORT Version: 2.0 Credit # 4772-IN Submitted by: Telecommunications Consultants India Limited TCIL Bhawan, Greater Kailash Part – I New Delhi- 110 048, India. TECHNICAL DESIGN REPORT TCIL Document Details Project Title Consultancy Services for Implementation of Component-A of Last Mile Connectivity of National Cyclone Risk Mitigation Project (NCRMP) Report Title Technical Design Report Report Version Version 2.0 Client State Project Implementation Unit (SPIU) National Cyclone Risk Mitigation Project - Kerala (NCRMP- Kerala) Department of Disaster Management Government of Kerala Report Prepared by Project Team Date of Submission 19.12.2018 TCIL’s Point of Contact Mr. A. Sampath Kumar Team Leader Telecommunications Consultants India Limited TCIL Bhawan, Greater Kailash-I New Delhi-110048 [email protected] Private & Confidential Page 2 TECHNICAL DESIGN REPORT TCIL Contents List of Abbreviations ..................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................... 9 2. EARLY WARNING DISSEMINATION SYSTEM .......................................................................................... 9 3. Objective of the Project ..................................................................................................................... -

Most Rev. Dr. M. Soosa Pakiam L.S.S.S., Thl. Metropolitan Archbishop of Trivandrum

LATIN ARCHDIOCESE OF TRIVANDRUM His Grace, Most Rev. Dr. M. Soosa Pakiam L.S.S.S., Thl. Metropolitan Archbishop of Trivandrum Date of Birth : 11.03.1946 Date of Ordination : 20.12.1969 Date of Episcopal Ordination : 02.02.1990 Metropolitan Archbishop of Trivandrum: 17.06.2004 Latin Archbishop's House Vellayambalam, P.B. No. 805 Trivandrum, Kerala, India - 695 003 Phone : 0471 / 2724001 Fax : 0471 / 2725001 E-mail : [email protected] Website : www.latinarchdiocesetrivandrum.org 1 His Excellency, Most Rev. Dr. Christudas Rajappan Auxiliary Bishop of Trivandrum Date of Birth : 25.11.1971 Date of Ordination : 25.11.1998 Date of Episcopal Ordination : 03.04.2016 Latin Archbishop's House Vellayambalam, P.B. No. 805 Trivandrum, Kerala, India - 695 003 Phone : 0471 / 2724001 Fax : 0471 / 2725001 Mobile : 8281012253, 8714238874, E-mail : [email protected] [email protected] Website : www.latinarchdiocesetrivandrum.org (Dates below the address are Dates of Birth (B) and Ordination (O)) 2 1. Very Rev. Msgr. Dr. C. Joseph, B.D., D.C.L. Vicar General & Chancellor PRO & Spokesperson Latin Archbishop's House, Vellayambalam, Trivandrum - 695 003, Kerala, India T: 0471-2724001; Fax: 0471-2725001; Mobile: 9868100304 Email: [email protected], [email protected] B: 14.04.1949 / O: 22.12.1973 2. Very Rev. Fr. Jose G., MCL Judicial Vicar, Metropolitan Archdiocesan Tribunal & Chairman, Archdiocesan Arbitration and Conciliation Forum Latin Archbishop's House, Vellayambalam, Trivandrum T: 0471-2724001; Fax: 0471-2725001 & Parish Priest, St. Theresa of Lisieux Church, Archbishop's House Compound, Vellayambalam, Trivandrum - 695 003 T: 0471-2314060 , Office ; 0471-2315060 ; C: 0471- 2316734 Web: www.vellayambalamparish.org Mobile: 9446747887 Email: [email protected] B: 06.06.1969 / O: 07.01.1998 3. -

Cyclone Ockhi

Public Inquest Team Members 1. Justice B.G. Kholse Patil Former Judge, Maharashtra High Court 2. Dr. Ramathal Former Chairperson, Tamil Nadu State Commission for Women 3. Prof. Dr. Shiv Vishvanathan Professor, Jindal Law School, O.P. Jindal University 4. Ms. Saba Naqvi Senior Journalist, New Delhi 5. Dr. Parivelan Associate Professor, School of Law, Rights and Constitutional Governance, TISS Mumbai 6. Mr. D.J. Ravindran Formerly with OHCHR & Director of Human Rights Division in UN Peace Keeping Missions in East Timor, Secretary of the UN International Inquiry Commission on East Timor, Libya, Sudan & Cambodia 7. Dr. Paul Newman Department of Political Science, University of Bangalore 8. Prof. Dr. L.S. Ghandi Doss Professor Emeritus, Central University, Gulbarga 9. Dr. K. Sekhar Registrar, NIMHANS Bangalore 10. Prof. Dr. Ramu Manivannan Department of Political Science, University of Madras 11. Mr. Nanchil Kumaran IPS (Retd) Tamil Nadu Police 12. Dr. Suresh Mariaselvam Former UNDP Official 13. Prof. Dr. Fatima Babu St. Mary’s College, Tuticorin 14. Mr. John Samuel Former Head of Global Program on Democratic Governance Assessment - United Nations Development Program & Former International Director - ActionAid. Acknowledgement Preliminary Fact-Finding Team Members: 1. S. Mohan, People’s Watch 2. G. Ganesan, People’s Watch 3. I. Aseervatham, Citizens for Human Rights Movement 4. R. Chokku, People’s Watch 5. Saravana Bavan, Care-T 6. Adv. A. Nagendran, People’s Watch 7. S.P. Madasamy, People’s Watch 8. S. Palanisamy, People’s Watch 9. G. Perumal, People’s Watch 10. K.P. Senthilraja, People’s Watch 11. C. Isakkimuthu, Citizens for Human Rights Movement 12. -

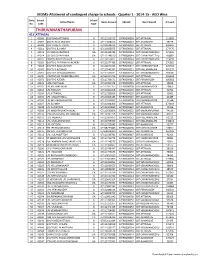

MDMS-Allotment of Contingent Charge to Schools - Quarter 1 - 2014-15 - AEO Wise

MDMS-Allotment of contingent charge to schools - Quarter 1 - 2014-15 - AEO Wise Code School School School Name Bank Account IFSCode Bank Branch Amount No. Code Type THIRUVANANTHAPURAM 423 ATTINGAL 1 42006 GOVT.BHS ATTINGAL G 67111616552 SBTR0000039 SBT ATTINGAL 111803 2 42007 GOVT.HSS ALAMCODE G 67111858456 SBTR0000667 SBT ALAMCODE 59229 3 42008 GOVT.GHS ATTINGAL G 67132614276 SBTR0000039 SBT ATTINGAL 229187 4 42011 GOVT.HS ELAMBA G 67112505555 SBTR0000039 SBT ATTINGAL 277475 5 42013 SCV BHS CHIRAYINKIL GA 67112428239 SBTR0000044 SBT CHIRAYINKEEZHU 121616 6 42014 SSV GHS CHIRAYINKIL GA 67112248610 SBTR0000044 SBT CHIRAYINKEEZHU 168092 7 42015 PNM HS KOONTHALLOR G 67112150011 SBTR0000044 SBT CHIRAYINKEEZHU 112033 8 42021 GOVT.HS AVANANAVANCHERY G 67112377485 SBTR0000039 SBT ATTINGAL 270581 9 42023 GOVT.HS KAVALAYOOR G 67112070463 SBTR0000347 SBT CHERUNNIYOOR 126703 10 42035 GOVT.HS NJEKKAD G 67110542395 SBTR0000221 SBT KALLAMBALAM 365137 11 42051 GOVT.HS VENJARAMOODU G 67111635031 SBTR0000254 SBT VENJARAMOODU 268785 12 42070 JANATHA HS THEMPAMOODU GA 67152191276 SBTR0000039 SBT ATTINGAL 255358 13 42072 GOVT.HS AZOOR G 67111735171 SBTR0000312 SBT PERUNGUZHI 185082 14 42301 LMSLPSATINGAL GA 67110367478 SBTR0000039 SBT ATTINGAL 39819 15 42302 LPS.KEEZHATINGAL G 67111917377 SBTR0000038 SBT KADAKKAVOOR 20863 16 42303 LPS ANDOOR G 67110960208 SBTR0000039 SBT ATTINGAL 30799 17 42304 LPS.ATTINGAL G 67111955856 SBTR0000039 SBT ATTINGAL 21851 18 42305 LPS. MELATTINGAL G 67110464483 SBTR0000667 SBT ALAMCODE 41489 19 42306 LPS MELKADAKKAVOOR G 67110742837 SBTR0000038 SBT KADAKKAVOOR 31548 20 42307 LPS.ELAMBA G 67111864469 SBTR0000039 SBT ATTINGAL 173914 21 42308 LPS ALAMCODE G 67112200869 SBTR0000667 SBT ALAMCODE 41356 22 42309 LPS MADATHUVATHUKKAL G 67110530809 SBTR0000052 SBT VAMANAPURAM 74110 23 42310 PTM LPS KUMPALATHUMPARA GA 67112281715 SBTR0000052 SBT VAMANAPURAM 42812 24 42311 .LPS. -

Download Socio-Economic Survey of Kovalam Forane

SOCIO-ECONOMIC AND PASTORAL SURVEY A REPORT AND ANALYSIS KOVALAM FORANE LATIN ARCHDIOCESE OF TRIVANDRUM Vellayambalam, Trivandrum Vol. 6 KOVALAM FORANE 1 SOCIO-ECONOMIC AND PASTORAL SURVEY 2011 A REPORT AND ANALYSIS KOVALAM FORANE Latin Archdiocese of Trivandrum, Vellayambalam Data Collection and Data Entry BCC & TSSS (Archdiocese of Trivandrum) Software Development Mr. Justus S. Data Analysis and Survey Report Dr. J. Mary John ADHWANA Resource Center, Thiruvananthapuram +91 944 797 1846 Design and Layout SKETCH +91 77 3650 2049 sketchtricks.com Survey Team Msgr. James Culas J. Fr. Sabbas Ignatius G.N. Fr. Edison Y.M. (Coordinator) Published by Latin Archdiocese of Trivandrum Archbishop’s House Compound Samanwaya, Vellayambalam Thiruvananthapuram - 3 © TSSS & BCC 2013, May 2 TRIVANDRUM LATIN ARCHDIOCESE. PLATINUM JUBILEE SURVEY-2011 Contents Preface 5 Foreward 7 Map 9 Archdiocesan History 11 Forane History 15 List of Chart 21 List of Table 23 Chapter1 27 Introduction and Methodology Chapter 2 33 Presentation of Data Chapter 3 93 Summary of Findings and Recommendations Annexure Annexure 1: Tables 103 Annexure 2: Schedule 247 KOVALAM FORANE 3 4 TRIVANDRUM LATIN ARCHDIOCESE. PLATINUM JUBILEE SURVEY-2011 Preface History always recalls National Census as one of the greatest achievements of any ruler who accomplishes it, precisely because it presupposes vision, systematic planning and sincere dream for sustainable development of his or her kingdom. 2012 was a milestone in the annals of the Latin Archdiocese of Trivandrum which celebrated its Platinum Jubilee that year. One of the important events which added colour and grandeur and substance was the socio-economic, pastoral and civic survey of the Archdiocesan population. -

AVM Canal Poovar to Erayumanthurai (11.30Km)

Final Feasibility Report National Waterway-13, Region VI - AVM Canal Poovar to Erayumanthurai (11.30km) SURVEY PERIOD: 20 DEC 2015 TO 18 FEB 2016 Volume - I Prepared for: Inland Waterways Authority of India (Ministry of Shipping, Govt. of India) A-13, Sector – 1, NOIDA Distt. GautamBudh Nagar, Document Distribution Date Revision Distribution Hard Copy Soft Copy INLAND WATERWAYS 31 Oct 2016 Rev – 0 01 01 AUTHORITY OF INDIA INLAND WATERWAYS 07 Jan 2017 Rev – 1.0 01 01 AUTHORITY OF INDIA INLAND WATERWAYS 31 Jan 2017 Rev – 1.1 01 01 AUTHORITY OF INDIA INLAND WATERWAYS 26 Sep 2017 Rev – 1.2 04 04 Uttar AUTHORITY OF INDIA Pradesh – INLAND WATERWAYS 23 Nov 2017 Rev – 1.3 01 01 AUTHORITY OF INDIA 201 301 INLAND WATERWAYS 26 Nov 2018 Rev – 1.4 04 04 AUTHORITY OF INDIA IWAI, Region VI, AVM Canal Final Feasibility Report Page II ACKNOWLEDGEMENT IIC Technologies Ltd. expresses its sincere gratitude to IWAI for awarding the work of carrying out detailed hydrographic surveys in the New National Waterways in NW- 13 in Region VI – AVM Canal from Poovar to Erayumanthurai. We would like to use this opportunity to pen down our profound gratitude and appreciations to Shri Pravir Pandey, IA&AS, Chairman IWAI for spending his valuable time and guidance for completing this Project. IIC Technologies Ltd, would also like to thanks, Shri Alok Ranjan, ICAS Member (Finance), Shri Shashi Bhushan Shukla, Member (Traffic), Shri S.K. Gangwar, Member (Technical) for their valuable support during the execution of project. IIC Technologies Ltd. wishes to express their gratitude to Capt. -

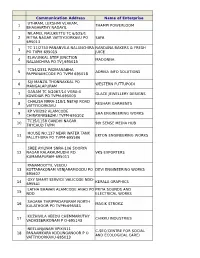

Communication Address Name of Enterprise 1 THAMPI

Communication Address Name of Enterprise UTHRAM, LEKSHMI VLAKAM, 1 THAMPI POWERLOOM BHAGAVATHY NADAYIL NILAMEL NALUKETTU TC 6/525/1 2 MITRA NAGAR VATTIYOORKAVU PO SAFA 695013 TC 11/2750 PANANVILA NALANCHIRA NANDANA BAKERS & FRESH 3 PO TVPM 695015 JUICE ELAVUNKAL STEP JUNCTION 4 MADONNA NALANCHIRA PO TV[,695015 TC54/2331 PADMANABHA 5 ADRIKA INFO SOLUTIONS PAPPANAMCODE PO TVPM 695018 SIJI MANZIL THONNAKKAL PO 6 WESTERN PUTTUPODI MANGALAPURAM GANAM TC 5/2067/14 VGRA-4 7 GLACE JEWELLERY DESIGNS KOWDIAR PO TVPM-695003 CHALISA NRRA-118/1 NETAJI ROAD 8 RESHAM GARMENTS VATTIYOORKAVU KP VIII/292 ALAMCODE 9 SHA ENGINEERING WORKS CHIRAYINKEEZHU TVPM-695102 TC15/1158 GANDHI NAGAR 10 9th SENSE MEDIA HUB THYCAUD TVPM HOUSE NO.137 NEAR WATER TANK 11 EKTON ENGINEERING WORKS PALLITHURA PO TVPM-695586 SREE AYILYAM SNRA-106 SOORYA 12 NAGAR KALAKAUMUDHI RD. VKS EXPORTERS KUMARAPURAM-695011 PANAMOOTTIL VEEDU 13 KOTTARAKONAM VENJARAMOODU PO DEVI ENGINEERING WORKS 695607 OXY SMART SERVICE VALICODE NDD- 14 KERALA GRAPHICS 695541 LATHA BHAVAN ALAMCODE ANAD PO PRIYA SOUNDS AND 15 NDD ELECTRICAL WORKS SAGARA THRIPPADAPURAM NORTH 16 MAGIK STROKZ KULATHOOR PO TVPM-695583 KUZHIVILA VEEDU CHEMMARUTHY 17 CHIKKU INDUSTRIES VADASSERIKONAM P O-695143 NEELANJANAM VPIX/511 C-SEC(CENTRE FOR SOCIAL 18 PANAAMKARA KODUNGANOOR P O AND ECOLOGICAL CARE) VATTIYOORKAVU-695013 ZENITH COTTAGE CHATHANPARA GURUPRASADAM READYMADE 19 THOTTAKKADU PO PIN695605 GARMENTS KARTHIKA VP 9/669 20 KODUNGANOORPO KULASEKHARAM GEETHAM 695013 SHAMLA MANZIL ARUKIL, 21 KUNNUMPURAM KUTTICHAL PO- N A R FLOUR MILLS 695574 RENVIL APARTMENTS TC1/1517 22 NAVARANGAM LANE MEDICAL VIJU ENTERPRISE COLLEGE PO NIKUNJAM, KRA-94,KEDARAM CORGENTZ INFOTECH PRIVATE 23 NAGAR,PATTOM PO, TRIVANDRUM LIMITED KALLUVELIL HOUSE KANDAMTHITTA 24 AMALA AYURVEDIC PHARMA PANTHA PO TVM PUTHEN PURACKAL KP IV/450-C 25 NEAR AL-UTHMAN SCHOOL AARC METAL AND WOOD MENAMKULAM TVPM KINAVU HOUSE TC 18/913 (4) 26 KALYANI DRESS WORLD ARAMADA PO TVPM THAZHE VILAYIL VEEDU OPP. -

TSSS Annual Report 2018 – 2019

REGISTERED IN 1960, UNDER THE T.C. LITERARY, SCIENTIFIC AND CHARITABLE SOCIETIES REGISTRATION ACT OF XII, 1955, REG. NO. 352/85 TSSS GOLDEN JUBILEE BUILDING ARCHBISHOP’S HOUSE COMPOUND, VELLAYAMBALAM THIRUVANANTHAPURAM- 695003 1 TSSS Annual Report 2018 – 2019 Editorial Team Patrons & Trustee Most Rev. Dr. Soosa Pakiam M. Rt. Rev. Dr. Christudas R. Managing Editor Rev. Fr. Sabbas Ignatius G.N. Chief Editor Mr. Thomas Thekkel Editorial Board Rev. Fr. Ashlin Jose Rev. Fr. John Dall Mrs. Jismy Jose Mrs. Sherly V.S. Design & layout Mrs. Sherly V.S. Trivandrum Socal Service Society Vellayambalam Trivandrum – 3 21-02-2020 2 MESSAGE FROM THE TRUSTEE I am pleased that our Social Action Ministry is functioning very well and through the Social Service Society we could address the current challenges of the society. The society’s participatory roles of activities have aroused the hidden talents and dormant commitments of many men and women for the benefit of the community and the society at large. The different programmes and projects to make the individual, family and the society liquor/drug free, the shelter project even to those who have no land, the health programmes - both preventive care and support - including the differently abled, caring individual family and their needs through Save A Family Programme, child care and protection programme, women empowerment programmes and skill development and income generation, caring the orphans and mentally retarded, job and skill trainings through the institutions, and reaching the needy of calamities and disasters, linkages with GOs and NGOs for the betterment of different kinds of labourers and Pravasies were very active during the year under report. -

Draft Industrial Potential Survey

DRAFT INDUSTRIAL POTENTIAL SURVEY DISTRICT :THIRUVANANTHAPURAM Introduction Thiruvananthapuram District is the southernmost district of the coastal state of Kerala, in south India. It came into existence in the year 1957. The headquarters is the city of Thiruvananthapuram (Trivandrum) which is also the capital city of Kerala. Thiruvananthapuram city and several other places in the district loom large in ancient tradition, folklore and literature. In 1684, during the regency of Umayamma Rani, the English East India Company obtained a sandy spit of land at Anchuthengu near Varkala on the sea coast about 32 kilometres (20 mi) north of Thiruvananthapuram city, with a view to erecting a factory and fortifying it. The place had earlier been frequented by the Portuguese and later by the Dutch. It was from here that the English gradually extended their domain to other parts of Travancore. Modern history begins with Marthanda Varma, 1729 CE – 1758 CE, who is generally regarded as the Father of modern Travancore. Thiruvananthapuram was known as a great centre of intellectual and artistic activities in those days. "Thiruvananthapuram" literally means "City of Lord Anantha". The name derives from the deity of the Hindu temple at the center of the Thiruvananthapuram city. Anantha is the mythical thousand hooded serpent- Shesha on whom Padmanabhan or Vishnu reclines. The temple of Vishnu reclining on Anantha, the Sri Padmanabhaswamy temple, which dates back to the 16th century, is the most-recognizable iconic landmark of the city as well as the district. Along with the presiding deity of SriPadmanabha, this temple also has temples inside it, dedicated to Lord Krishna and Lord Narasimha, Lord Ganesha, and Lord Ayyappa. -

Fishermen's Cooperatives in Kerala: a Critique – BOBP/MIS/01

BAY OF BENGAL PROGRAMME BOBP/MIS/1 Development of Small-Scale Fisheries (GCP/RAS/040/SWE) FISHERMEN’S COOPERATIVES BOBP/MIS/1 IN KERALA: A CRITIQUE By John Kurien Executing Agency : Funding Agency Food and Agriculture Organisation Swedish International of the United Nations Development Authority Development of Small-Scale Fisheries in the Bay of Bengal Madras, India, October 1980 PREFACE This paper briefly discusses the history of fishermen’s cooperatives in Kerala and the reasons for their disappointing performance. It also describes the experience of a successful fisheries cooperative - in Marianad village of Trivandrum district - and analyses the reasons for its success. The paper was presented at the Workshop on Social Feasibility in Small-Scale Fisheries Develop- ment held in Madras, September 4-8, 1979. The workshop was hosted by the Government of Tamil Nadu in cooperation with the Bay of Bengal Programme (BOBP). The paper may be of interest to small-scale fisheries planners, as also to individuals and institutions who are concerned with the cooperative movement and with the social and economic uplift of small-scale fishing communities. The author, John Kurien, is a research associate at the Centre for Development Studies, Trivandrum. He also works in an honorary capacity with the Fisheries Research Cell of the Programme for Community Organization, an independent agency. He was actively involved with the Marianad cooperative during its earliest days. The opinions expressed in the paper are entirely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Bay of Bengal Programme or of the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations. -

District Wise IT@School Master District School Code School Name Thiruvananthapuram 42006 Govt

District wise IT@School Master District School Code School Name Thiruvananthapuram 42006 Govt. Model HSS For Boys Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42007 Govt V H S S Alamcode Thiruvananthapuram 42008 Govt H S S For Girls Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42010 Navabharath E M H S S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42011 Govt. H S S Elampa Thiruvananthapuram 42012 Sr.Elizabeth Joel C S I E M H S S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42013 S C V B H S Chirayinkeezhu Thiruvananthapuram 42014 S S V G H S S Chirayinkeezhu Thiruvananthapuram 42015 P N M G H S S Koonthalloor Thiruvananthapuram 42021 Govt H S Avanavancheri Thiruvananthapuram 42023 Govt H S S Kavalayoor Thiruvananthapuram 42035 Govt V H S S Njekkad Thiruvananthapuram 42051 Govt H S S Venjaramood Thiruvananthapuram 42070 Janatha H S S Thempammood Thiruvananthapuram 42072 Govt. H S S Azhoor Thiruvananthapuram 42077 S S M E M H S Mudapuram Thiruvananthapuram 42078 Vidhyadhiraja E M H S S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42301 L M S L P S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42302 Govt. L P S Keezhattingal Thiruvananthapuram 42303 Govt. L P S Andoor Thiruvananthapuram 42304 Govt. L P S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42305 Govt. L P S Melattingal Thiruvananthapuram 42306 Govt. L P S Melkadakkavur Thiruvananthapuram 42307 Govt.L P S Elampa Thiruvananthapuram 42308 Govt. L P S Alamcode Thiruvananthapuram 42309 Govt. L P S Madathuvathukkal Thiruvananthapuram 42310 P T M L P S Kumpalathumpara Thiruvananthapuram 42311 Govt. L P S Njekkad Thiruvananthapuram 42312 Govt. L P S Mullaramcode Thiruvananthapuram 42313 Govt. L P S Ottoor Thiruvananthapuram 42314 R M L P S Mananakku Thiruvananthapuram 42315 A M L P S Perumkulam Thiruvananthapuram 42316 Govt. -

Public Works Department Buildings

PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT BUILDINGS OFFICE OF THE ENGINEER-IN-CHIEF (BUILDINGS), CHIEF ENGINEER (BUILDINGS) CHENNAI REGION AND CHIEF ENGINEER (GENERAL), PWD., CHEPAUK, CHENNAI – 5 GUIDELINES FOR PLANNING, DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION OF BUILDINGS WITH RESPECT TO FIRE, EARTHQUAKE, CYCLONE, FLOOD, TSUNAMI AND OTHER HAZARDS Zone - III Moderate Intensity Zone Zone - II Low Intensity Zone MAP OF EARTHQUAKE ZONES IN TAMIL NADU Tamilaga Arasu Building Research Station, PWD, Taramani, Chennai-600 113 PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT BUILDINGS OFFICE OF THE ENGINEER-IN-CHIEF (BUILDINGS) & CHIEF ENGINEER (BUILDINGS) CHENNAI REGION AND CHIEF ENGINEER (GENERAL), PWD., CHEPAUK, CHENNAI – 600 005 Technical Circular No. AEE/T10/24475/2017, dated 27.10.2017 Sub : Disaster Management - Guidelines for Planning, Design and Construction of buildings with respect to Fire, Earthquake, Cyclone, Flood, Tsunami and other hazards-Regarding. This circular is issued to all the Superintending Engineers and Executive Engineers of Tamilnadu Public Works Department with Guidelines for Planning, Design and Construction with respect to Fire, Earthquake, Tsunami, Cyclone, Flood and other hazards. Disaster prevention involves engineering intervention in buildings and structures to make them strong enough to withstand natural hazard so that the exposure of the society to hazard situation could be avoided or minimized. Public Works department buildings organization is committed to Plan, design, construct and maintain the Public Buildings and monitor the stability of the public buildings.