Endangered Species Act: Beyond Collective Rights for Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books

I LLINOJ S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. BULLETIN THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LIBRARY * CHILDREN'S BOOK CENTER Volume IX July, 1956 Number 11 EXPLANATION OF CODE SYMBOLS USED WITH ANNOTATIONS R Recommended M Marginal book that is so slight in content or has so many weaknesses in style or format that it barely misses an NR rating. The book should be given careful consideration before purchase. NR Not recommended. Ad For collections that need additional material on the subject. SpC Subject matter or treatment will tend to limit the book to specialized collections. SpR A book that will have appeal for the unusual reader only. Recommended for the special few who will read it. step in the process. At the end there is a simple experiment that children could do at home. A useful book for units on foods or industries. A" W andan ?1ouz "Eofsh R Adler, Irving. Fire in Your Life; illus. R Annixter, Jane and Paul. The Runner; 6-9 by Ruth Adler. Day, 1955. 128p. 7-9 drawings by Paul Laune. Holiday House, $2.75 1956. 220p. $2.75. In much the same style as his Time in Your Clem Mayfield (Shadow), an orphan living with Life and Tools in Your Life, the author traces his aunt and uncle on their Wyoming ranch, is the history of man's use of fire from primitive recovering from a bout with polio that left him to modern times. Beginning with some of the with a limp but still able to ride. -

The Aquatic Ape Hypothesis: Most Credible Theory of Human Evolution Free Download

THE AQUATIC APE HYPOTHESIS: MOST CREDIBLE THEORY OF HUMAN EVOLUTION FREE DOWNLOAD Elaine Morgan | 208 pages | 01 Oct 2009 | Souvenir Press Ltd | 9780285635180 | English | London, United Kingdom Aquatic ape hypothesis In addition, the evidence cited by AAH The Aquatic Ape Hypothesis: Most Credible Theory of Human Evolution mostly concerned developments in soft tissue anatomy and physiology, whilst paleoanthropologists rarely speculated on evolutionary development of anatomy beyond the musculoskeletal system and brain size as revealed in fossils. His summary at the end was:. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Thanks for your comment! List of individual apes non-human Apes in space non-human Almas Bigfoot Bushmeat Chimpanzee—human last common ancestor Gorilla—human last common ancestor Orangutan—human last common ancestor Gibbon —human last common ancestor List of fictional primates non-human Great apes Human evolution Monkey Day Mythic humanoids Sasquatch Yeren Yeti Yowie. Thomas Brenna, PhD". I think that we need to formulate a new overall-theory, a new anthropological paradigm, about the origin of man. This idea has been flourishing since Charles Darwin and I think that many scientists and laymen will have difficulties in accepting the Aquatic Ape Hypothesis — as they believe in our brain rather than in our physical characteristics. Last common ancestors Chimpanzee—human Gorilla—human Orangutan—human Gibbon—human. I can see two possible future scenarios for the Aquatic Ape Theory. University The Aquatic Ape Hypothesis: Most Credible Theory of Human Evolution Chicago Press. Human Origins Retrieved 16 January The AAH is generally ignored by anthropologists, although it has a following outside academia and has received celebrity endorsement, for example from David Attenborough. -

Calamity for Wild Orangutans in Borneo

et21/1 oge Sees—e eaica ouce as ao a ami- isao wo ee o ou e Aima Weae Isiue a see as is easue o yeas—waks wi e Seeses og May See ou aecia- io o M Sees o age 13 May ese was a ieesig caace; se was aoe y e Seeses ae a aumaic eay ie as a say o og Isa Se ie i 199 vr pht b ln Mr rtr Maoie Cooke ai i eick uciso eeo G ewe Cisie Sees Cyia Wiso Oices Cisie Sees esie Cyia Wiso ice esie eeo G ewe Seceay eick uciso easue Sntf Ctt Maoie Ace Gea ea ee ey M aaa Oas "Tamworth Two" Win Fame by Cheating the Butcher oge aye The two pigs shown above, ickame uc Cassiy a Suace ig Samue eacock M o Was M wee e suec owiesea uic symay i auay we ey escae om a Mamesuy Ega aaoi soy eoe ey wee o e saug- Intrntnl Ctt ee Aie e Au a M - Meico We ey saw ei oe kie e ime gige-cooe igs eue G Aikas M - Geece saugeouse wokes wo case em o e miues i uc wigge Amassao aaak usai - agaes oug a oe i e wa a Suace oowe ey e swam acoss e Agea Kig - Uie Kigom ie Ao o a sma woo ey se si ays o e u uig wic ey Simo Muciu - Keya cause quie a o o meia a uic aeio as we as comica eos o Gooeo Sui - Cie aee em Ms umiiko ogo - aa Kaus esegaa - emak ey wee eeuay caug uc (acuay a emae was coee i a AeeyYaoko - ussia ie wie Suace was aquiie y e SCA I ig o e ooiey e ocie escaees a wo ei owe cage is mi aou aig Stffnd Cnltnt em saugee a ey wi ie ou ei ies i a aima sacuay eay Comue Cosua o Geie Assisa o e Oices iae aeso am Aima Cosua ...But Slaughterhouse Conditions Are No LaughingMatter ye uciso Wae Camaig Cooiao oug e amwo wos sow a a ay eig saugeouse Cay iss Eecuie ieco coiios ae ayig u -

From Your PTA Co-President, Margaret Editor: Laurie Weissman Happy Spring Everyone! You I Don’T Think I Could Have Made It Through the Year

Volume 11, Issue 2 June, 2011 From your PTA Co-President, Margaret Editor: Laurie Weissman Happy Spring everyone! you I don’t think I could have made it through the year. These Moms are so As I look around our school, I see the resourceful, caring and most of all dedi- flowers blooming and hear the cheer- cated in everything they do. A hug goes ful giggles of children. It reminds me to my Co-President Leslie, great job! that spring is here and summer is not Her dedication and support made this too far away. The halls and play- year a fun and enjoyable one. Leslie you ground are full of life and excitement. have so many great ideas, keep going, we I see the changes in the children, they all could benefit from them. I don’t like all seem so confident and sure of to say goodbye so I'll say see you all themselves. It is hard to believe that later. I am confident that with our new another year at Lee Road has gone so Co-President Roma and the wise knowl- quickly. This year seemed to fly by so edge of Leslie our school PTA is going to fast. I think one reason was due to the be a strong one. I want to wish the amount of support I had. I would like graduating fifth graders a big congrats to thank Mr. Goss for helping and and best wishes in Salk. I'd like to end supporting me and the PTA. When with saying I hope everyone has a fun you have a principal that is open to filled summer. -

Menagerie to Me / My Neighbor Be”: Exotic Animals and American Conscience, 1840-1900

“MENAGERIE TO ME / MY NEIGHBOR BE”: EXOTIC ANIMALS AND AMERICAN CONSCIENCE, 1840-1900 Leslie Jane McAbee A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2018 Approved by: Eliza Richards Timothy Marr Matthew Taylor Ruth Salvaggio Jane Thrailkill © 2018 Leslie Jane McAbee ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Leslie McAbee: “Menagerie to me / My Neighbor be”: Exotic Animals and American Conscience, 1840-1900 (Under the direction of Eliza Richards) Throughout the nineteenth century, large numbers of living “exotic” animals—elephants, lions, and tigers—circulated throughout the U.S. in traveling menageries, circuses, and later zoos as staples of popular entertainment and natural history education. In “Menagerie to me / My Neighbor be,” I study literary representations of these displaced and sensationalized animals, offering a new contribution to Americanist animal studies in literary scholarship, which has largely attended to the cultural impact of domesticated and native creatures. The field has not yet adequately addressed the influence that representations of foreign animals had on socio-cultural discourses, such as domesticity, social reform, and white supremacy. I examine how writers enlist exoticized animals to variously advance and disrupt the human-centered foundations of hierarchical thinking that underpinned nineteenth-century tenets of civilization, particularly the belief that Western culture acts as a progressive force in a comparatively barbaric world. Both well studied and lesser-known authors, however, find “exotic” animal figures to be wily for two seemingly contradictory reasons. -

(Tableau Des Électeurs Sénatoriaux

ELECTIONS SENATORIALES TABLEAU DES ELECTEURS Commune Civ nom prénom qualité Remplaçant de M JÉGO Yves Député M JACOB Christian Député M RIESTER Franck Député M PARIGI Jean-François Député M KOKOUENDO Rodrigue Député M FAUVERGUE Jean-Michel Député M FAURE Olivier Député Mme LUQUET Aude Député Mme PEYRON Michèle Député MmeDO Stéphanie Député Mme LACROUTE Valérie Député M BILLOUT Michel Sénateur Mme BRICQ Nicole Sénateur Mme CHAIN-LARCHE Anne Sénateur M CUYPERS Pierre Sénateur M EBLÉ Vincent Sénateur Mme MELOT Colette Sénateur Mme BADRÉ Marie Pierre Conseiller régional M BATTAIL Gilles Conseiller régional M BOLLÉE Joffrey Conseiller régional M DEROUCK Marc Conseiller régional Madame Anne CHAIN-LARCHÉ M CHÉRON James Conseiller régional 1/232 ELECTIONS SENATORIALES TABLEAU DES ELECTEURS Commune Civ nom prénom qualité Remplaçant de M CHERRIER Pierre Conseiller régional M CHEVRON Benoît Conseiller régional Mme COURNET Aurélie Conseiller régional M CUZOU Gilbert Conseiller régional M DUTHEIL DE LA ROCHERE Bertrand Conseiller régional Mme FUCHS Sylvie Conseiller régional M JEUNEMAITRE Eric Conseiller régional M KALFON François Conseiller régional Mme MOLLARD-CADIX Laure-Agnès Conseiller régional Mme MONCHECOURT Sylvie Conseiller régional Mme MONVILLE-DE CECCO Bénédicte Conseiller régional M PLANCHOU Jean-Paul Conseiller régional M PROFFIT Julien Conseiller régional Mme REZEG Hamida Conseiller régional Mme SARKISSIAN Roseline Conseiller régional Mme THOMAS Claudine Conseiller régional Mme TROUSSARD Béatrice Conseiller régional M VALLETOUX Frédéric -

Mens a Jason Daniels Richard Dunn John Meeks ADULT

DIVISION TEAM PLAYER ONE PLAYER TWO PLAYER THREE ADULT - Mens A Jason Daniels Richard Dunn John Meeks ADULT - Mens A Mayhem Lee Binkley Mark Binkley Austin Neiheiser ADULT - Mens A COVID Spikes Cameron Brence Logan Brence Chanse Myers ADULT - Mens A Stoned Aged Romeos Jason Lewis Tim Dudley Maeson LuCan ADULT - Mens A Dig My Ballz Tommy Criss John Owens Owen Sease ADULT - Mens A CHHS Bois Nathan Dye Zin Maung Drew Campbell ADULT - Mens A Burhan Bustillos Jay Park Elliot Kim ADULT - Mens A I'd Hit That Zach Lamoureux Hayden Lichty Hunter Davis ADULT - Mens A The 1995 Wisconsin Badgers Patrick Shugart Kevin Troupe Joel Cordray ADULT - Mens A Don't Set Sarum Sarum Rich Micah Johnson Christian Sullivan ADULT - Mens A Justin Burgess Addison Musser ADULT - Mens BB Hit Men Andrew Wild Andrew Cecil Jeremy Wollman ADULT - Mens BB We ALWAYS get it up Scott Drogue Nolan Franz Timmy Shaw ADULT - Mens BB Nguyen Tran TBD TBD TBD TBD ADULT - Mens BB The Chimps stephen carbone Stephen carbone kenny nguyen ADULT - Mens BB Hang 10 Matt Lenora Blaine Ott David Mumford ADULT - Mens BB The Heat Brandon Wooding Gary Biggs Darius Swanson ADULT - Mens BB Block Heads Charlie Sapp Johnny Kearns Kane Laah ADULT - Mens BB What the Pho. Jp Phetx Andy Inth Phy Phy ADULT - Mens BB Barry Rymer Artie Sykes Danny Sutton ADULT - Mens BB Bum Squad Trevor Chaney Quan Pratt Caleb Williams ADULT - Mens BB Raleigh Raccoons Sion Tran David Eban Sam Vong ADULT - Mens BB Ken Phanhvilay Lefoi Falemalama Dustin Rhodes ADULT - Mens BB Just three bros Peyton Robinson Chris Burkett -

The Welfare of Zoo-Housed Chimpanzees (Pan Troglodytes) with Special Attention to Auditory Enrichment

The Welfare of Zoo-housed Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) with Special Attention to Auditory Enrichment Emma Katherine Wallace PhD University of York Psychology November 2016 Abstract Modern zoos house millions of wild animals but also aim to conduct animal research, educate visitors about the natural world and support conservation programmes via funding and encouraging wildlife-friendly actions by the public. However, the benefit to conservation efforts and species living in the wild, through fundraising and increasing public awareness, may come at the cost of the animals living within zoos. In this thesis I focussed on the welfare of zoo-housed chimpanzees due to their endangered status and public popularity. I investigated potential social, dietary and visitor related triggers for anxiety-related behaviours (yawning and scratching) and regurgitation and reingestion (R/R). Despite interesting trends, no immediate triggers for these behaviours were found. However, long-term data showed the frequency with which individuals engage in R/R reduced over time when part of a complex group inhabiting an enclosure encouraging natural behaviours and social dynamics. I also examined if music, frequently broadcast to captive chimpanzees, provides any enriching effect on their welfare. Both observational and experimental research suggested that whilst music does not appear to have any obvious positive welfare effects it is equally not detrimental. The final study explored whether public education, one of assumed benefits associated with having animals in zoos, is achieved via ‘Keeper Talks’. They were effective at demonstrating to adult visitors that touchscreens are an effective form of enrichment for chimpanzees but the talks had no significant effect on their knowledge of other issues covered, or any area of knowledge in young people. -

The Meaning of the Great Ape Project

POLITICS AND ANIMALS ISSUE 1 I FALL I 2015 The Meaning of the Great Ape Project PAOLA CAVALIERI Independent Researcher It is now more than two decades since the Great Ape Project was launched. How does such a cultural Keywords: and political initiative fit in the ongoing construction of a politics of animal liberation, and in the larger egalitarianism; contemporary moral and social landscape? An albeit tentative answer to this question will be possible nonhuman great apes; only in the context of an illustration of what the Great Ape project is—of its starting point, its articula- personhood; tion, and the objections it elicited. liberation THE PREMISES community may be arranged on the basis of extensive, super-scientific explanations of things (M. Warnock, Should the deeper sense of the idea of equality, 1990, p. 105)—that, in other words, individuals can be on which human rights is based, demand that we treated according to their alleged place within grand gen- provide for the interests and needs of humans eral worldviews built to explain the universe. While in but allow discrimination against the interests and pre-modern philosophy metaphysics predominated over needs of nonhuman beings? Wouldn’t it be ethics, and ethics was based on values which were deter- strange if the same idea contains the claim for mined by particular conceptions of Being, starting at equality and the permission for discrimination least from Henry Sidgwick (1981, B. I, Chapter 3, B. IV, too? (Anstötz, 1993, p. 169) Conclusion) a consensus slowly emerged that in ethics We live in egalitarian times. -

Step up List

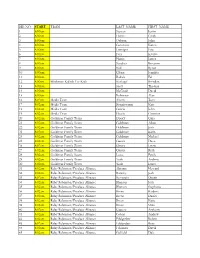

BIB NO. START TEAM LAST_NAME FIRST_NAME 1 8:00am Stewart Justin 2 8:00am Harris Cindy 3 8:00am Osborn John 4 8:00am Geninatti Karen 5 8:00am Leninger Eric 6 8:00am Frey Kristin 7 8:00am Harris James 8 8:00am Sanchez Roxanne 9 8:00am Noll Byron 10 8:00am Glenn Jennifer 11 8:00am Badida Ed 12 8:00am Blackman Kallick For Kids Kinkopf Brendan 13 8:00am Scott Thomas 14 8:00am McGrath David 15 8:00am Robinson Alan 16 8:02am Media Team Ahern Tom 17 8:02am Media Team Bongiovanni Kate 18 8:02am Media Team Garcia John 19 8:02am Media Team Garcia Christine 20 8:02am Goldman Family Team Doocy Gina 21 8:02am Goldman Family Team Goldman Adam 22 8:02am Goldman Family Team Goldman Josh 23 8:02am Goldman Family Team Goldman Karla 24 8:02am Goldman Family Team Goldman Michael 25 8:02am Goldman Family Team Gussis Dave 26 8:02am Goldman Family Team Gussis Lizzie 27 8:02am Goldman Family Team Gussis Ruth 28 8:02am Goldman Family Team Lowe Emily 29 8:02am Goldman Family Team York Andrew 30 8:02am Goldman Family Team York Laura 31 8:02am Ruby Robinson/Produce Alliance Abrams Howard 32 8:02am Ruby Robinson/Produce Alliance Barasky Jodi 33 8:02am Ruby Robinson/Produce Alliance Bernstein Dustin 34 8:02am Ruby Robinson/Produce Alliance Blanton Josh 35 8:02am Ruby Robinson/Produce Alliance Blanton Stephanie 36 8:02am Ruby Robinson/Produce Alliance Breen Barbara 37 8:02am Ruby Robinson/Produce Alliance Breen Daniel 38 8:02am Ruby Robinson/Produce Alliance Breen Katie 39 8:02am Ruby Robinson/Produce Alliance Breen Mike 40 8:02am Ruby Robinson/Produce Alliance Capone -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

The Compassion Arts & Culture and Animals Festival

The Compassion Arts & Culture and Animals Festival Featuring the World Premiere of And the Hummingbird Says . by Mihoko Suzuki and Martin Rowe Leonard Nimoy Thalia Theater at Symphony Space 2537 Broadway, New York City Saturday October 21, 2017: 1:45–3:45 pm and 7:30–10:30 pm Sunday October 22, 2017: 1:45–5:30 pm and 7:30–11:00 pm plus an art exhibition: Friday 5:00 pm–Sunday 6:00 pm at 208 E. 73rd St. Art Show: Beasts of Burden Festival Schedule Our Complex Relationship with Animals Featuring art by Jo-Anne McArthur, Moby, Performances Jennifer Wynne Reeves, Jane O’Hara, Karen Fiorito, Nancy Diessner, Wendy Klemperer, Tony Openings Bevilacqua, Denise Lindquist, Gedas Paskauskas, Ariel Bordeaux, Adonna Khare, Raul Gonzalez III, Julia Oldham, and Moira McLaughlin. Events O’Hara Projects. 208 East 73rd Street SUNDAY OCTOBER 22—AFTERNOON (Off Third Ave at TUF Gallery) 11 am–6 pm: Art Show: Beasts of Burden FRIDAY OCTOBER 20 O’Hara Projects. 208 East 73rd Street. 5–8 pm: Art Show: Beasts of Burden Reception 1:45 pm: Introduction and Welcome 2:00 pm: The Music of Michael Harren: a multi- SATURDAY OCTOBER 21—AFTERNOON media performance blending humor with candor 11 am–6 pm: Art Show: Beasts of Burden to convey the importance of keeping all animals O’Hara Projects. 208 East 73rd Street. safe from harm. With string quartet. 1:45 pm: Introduction and Welcome 3:00 pm: Break 2:00 pm: And the Hummingbird Says . : Composed 3:15 pm: Kedi (2016): dir. by Ceyda Torun, about the by Mihoko Suzuki, with words by Martin street cats of Istanbul.