Eynsham Abbey 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hawthorns Cote Road, Aston, Bampton, Oxfordshire OX18 2EB

Stow-on-the-Wold J10 A435 J11 CHELTENHAM A4260 Bourton-on-the-Water A44 A4095 A40 A361 J9 A41 GLOUCESTER A429 A424 A436 J11A A34 M5 Cotswolds A46 A4260 AONB A40 A4095 Burford M40 A435 WITNEY A429 A40 A417 A40 Carterton A4095 A415 A361 OXFORD CIRENCESTER B4449 J8/8A A419 A34 A415 J7 A417 ASTON A329 Lechlade- A4074 A4095 A338 A420 on-Thames A417 Abingdon Chitern Hills A433 A415 AONB Faringdon A415 A361 A338 A419 A429 A417 A4074 A420 A4130 Didcot Wantage A4130 SWINDON A417 M4 A4074 A34 J16 A338 J15 J17 A3102 A329 A4361 A346 M4 A420 J14 J13 READING North Wessex M4 Downs AONB M4 A4 Hawthorns Cote Road, Aston, Bampton, Oxfordshire OX18 2EB A40 A40 OXFORD Location CHELTENHAM Witney Hawthorns offers a collection of executive detached homes consisting of 2 bedroom bungalows and 4 & 5 Brize bedroom houses located in the village of Aston in the Norton A4095 A415 Ducklington Oxfordshire countryside. S T A N D L A K E Carterton D R The village of Aston has all the essentials of village Lew A O O A R D Hardwick N life - a church, a school and a pub. O T S B44 A 49 AD EYNSHAM R O A415 DOVER Aston is also home to the popular Aston Pottery and STATION ROAD nearby you will find Chimney Meadows, a 250 hectare nature reserve, rich in wildlife, along the banks of Hawthorns T S Brighthampton H T the Thames. Bampton ASTON R ABINGDON ROAD ASTON O D RD N E R OT B C AM RD B444 Standlake A4095 PT N B 9 O U Cote B L L ST A little over two miles away is the village of Bampton, U C K L A BAMPTON RD N one of the oldest villages in England, boasting a D R O RIV ER S A T H A ME village shop, Post Office, butcher, and traditional Clanfield D pubs serving good food and real ales, all set around A415 a pretty market square. -

REPORTS a Prehistoric Enclosure at Eynsham Abbey, Oxfordshire

REPORTS A Prehistoric Enclosure at Eynsham Abbey, Oxfordshire B) A 13 \RCI_~\, A 13m If and C.O. Ktf\lu. with contributions by A. BAYliS'>, C. BRO,\K Ibw,E1, T Ol RIl~,\, C. II \\ Ilf', J. ML L\ ILLf., P. ORIIIO\ f Rand E Rm SL i\IM.\R\ Part oj fl pr,hi\lnric ",rlm,,,.,. ditch U'(l\ e;vm'llltd Imor 10 Ilu' '.\/t'Il\lOU of Iht' grm't')"nd, of tlU' r/1IlJ(lit'\ oj St. Pt'tn\ mill St, LI'fJ1wrd\ E.lJl.\IUlm, O.t/orrN,i,.". I .nlr Rrtltlu- JIK' arttlarh u'rrt' jOlmd ;'llht lIppl'r Jt/t\ oj tlw (III(h Iml "L\ pn ....HUt that II U'flj (Q1uJru{/ed fllllln. ""IWI)' mill, Xfoli/hl(. UOPl~idt thl' lair 8m"ZI Igt' Ina/rna/, arltjar(\ oj StOWhl( and Bruhn/nat) 8wIIU' tw' datI' lL'f'I" (li\l) wl'ntified I pm."bll' lOlWdlw/HI' glllly. a l1wnhn oj /,i/\ and pm/lwft'\, mlll arl'W oj grmmd HlrjlICf. aI/ oj lalt 8r01l:..I' IKl'dalr ll'err joulld malIn IIIf' rnrlO\ll1f. Si.\ radu){mluJJI d(ltt,.~ tl'l'rt' obl/lllmi till mll/fnal dfrnmzgjl"Om til,. mrlo\llrt' ditch JiI/\ ami LIII' In""i~/{Jnr Kl'tul1Id ,\/irlflu, 11\ I ROIH ClIO~ hc Oxford Archaeological Unit (O.\l) eXGI\:~Ht'd an area of approximatel)' I HOOm.2 T \vilhill the Inner Ward or COUll of l-~y nsham .\boc) during 1990~92, The eXGI\,HIOnS were 1ll~\(lc nece:-.sall b) proposed cel11eter~ extensioll'i, and were \\holl) funded b) English Iledt4tgl'. -

Thames Valley Papists from Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829

Thames Valley Papists From Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829 Tony Hadland Copyright © 1992 & 2004 by Tony Hadland All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without prior permission in writing from the publisher and author. The moral right of Tony Hadland to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 9547547 0 0 First edition published as a hardback by Tony Hadland in 1992. This new edition published in soft cover in April 2004 by The Mapledurham 1997 Trust, Mapledurham HOUSE, Reading, RG4 7TR. Pre-press and design by Tony Hadland E-mail: [email protected] Printed by Antony Rowe Limited, 2 Whittle Drive, Highfield Industrial Estate, Eastbourne, East Sussex, BN23 6QT. E-mail: [email protected] While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, neither the author nor the publisher can be held responsible for any loss or inconvenience arising from errors contained in this work. Feedback from readers on points of accuracy will be welcomed and should be e-mailed to [email protected] or mailed to the author via the publisher. Front cover: Mapledurham House, front elevation. Back cover: Mapledurham House, as seen from the Thames. A high gable end, clad in reflective oyster shells, indicated a safe house for Catholics. -

11 Witney - Hanborough - Oxford

11 Witney - Hanborough - Oxford Mondays to Saturdays notes M-F M-F S M-F M-F Witney Market Square stop C 06.14 06.45 07.45 - 09.10 10.10 11.15 12.15 13.15 14.15 15.15 16.20 - Madley Park Co-op 06.21 06.52 07.52 - - North Leigh Masons Arms 06.27 06.58 07.58 - 09.18 10.18 11.23 12.23 13.23 14.23 15.23 16.28 17.30 Freeland Broadmarsh Lane 06.35 07.06 08.07 07.52 09.27 10.27 11.32 12.32 13.32 14.32 15.32 16.37 17.40 Long Hanborough New Road 06.40 07.11 08.11 07.57 09.31 10.31 11.36 12.36 13.36 14.36 15.36 16.41 Eynsham Spareacre Lane 06.49 07.21 08.20 09.40 10.40 11.45 12.45 13.45 14.45 15.45 16.50 Eynsham Church 06.53 07.26 08.24 08.11 09.44 10.44 11.49 12.49 13.49 14.49 15.49 16.54 17.49 Botley Elms Parade 07.06 07.42 08.33 08.27 09.53 10.53 11.58 12.58 13.58 14.58 15.58 17.03 18.00 Oxford Castle Street 07.21 08.05 08.47 08.55 10.07 11.07 12.12 13.12 13.12 15.12 16.12 17.17 18.13 notes M-F M-F S M-F M-F S Oxford Castle Street E2 07.25 08.10 09.10 10.15 11.15 12.15 13.15 14.15 15.15 16.35 16.35 17.35 17.50 Botley Elms Parade 07.34 08.20 09.20 10.25 11.25 12.25 13.25 14.25 15.25 16.45 16.50 17.50 18.00 Eynsham Church 07.43 08.30 09.30 10.35 11.35 12.35 13.35 14.35 15.35 16.55 17.00 18.02 18.10 Eynsham Spareacre Lane 09.34 10.39 11.39 12.39 13.39 14.39 15.39 16.59 17.04 18.06 18.14 Long Hanborough New Road 09.42 10.47 11.47 12.47 13.47 14.47 15.47 17.07 17.12 18.14 18.22 Freeland Broadmarsh Lane 07.51 08.38 09.46 10.51 11.51 12.51 13.51 14.51 15.51 17.11 17.16 18.18 18.26 North Leigh Masons Arms - 08.45 09.55 11.00 12.00 13.00 -

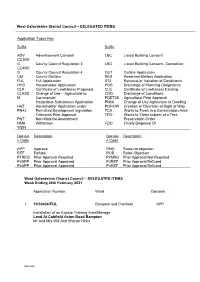

DELEGATED ITEMS Agenda Item No

West Oxfordshire District Council – DELEGATED ITEMS Agenda Item No. 5 Week Ending 6th February 2015 Application Types Key Suffix Suffix ADV Advertisement Consent LBC Listed Building Consent CC3REG County Council Regulation 3 LBD Listed Building Consent - Demolition CC4REG County Council Regulation 4 OUT Outline Application CM County Matters RES Reserved Matters Application FUL Full Application S73 Removal or Variation of Condition/s HHD Householder Application POB Variation of Planning Obligation/s CLP Certificate of Lawfulness Proposed CLE Certificate of Lawfulness Existing Decision Description Decision Description Code Code APP Approve RNO Raise no objection REF Refuse ROB Raise Objection West Oxfordshire District Council – DELEGATED ITEMS Application Number. Ward. Decision. 1. 14/1357/P/FP Eynsham and Cassington APP Erection of building to create 6 classrooms, 2 science labs and ancillary facilities. Bartholomew School Witney Road Eynsham Bartholomew Academy 2. 14/01997/ADV Witney West APP Erection of internally illuminated sign Oxford House Unit 2 De Havilland Way Windrush Industrial Park 3. 14/02018/FUL Eynsham and Cassington APP Affecting a Conservation Area Erection of new dwelling The Shrubbery 26 High Street Eynsham Dr Max & Joanna Peterson 4. 14/02022/HHD Brize Norton and Shilton APP Form improved vehicular access. Construct detached double garage with games room over. Construct small greenhouse. Erection of boundary fence from new garage to join up with existing fence Yew Tree Cottage 60 Station Road Brize Norton Mr P Granville Agenda Item No. 5, page 1 of 7 5. 14/02106/HHD Ducklington APP Removal of existing garage, lean-to and rear playroom. Erection of single and two-storey extensions to front, side and rear elevations. -

Applications Determined Under Delegated Powers PDF 317 KB

West Oxfordshire District Council – DELEGATED ITEMS Application Types Key Suffix Suffix ADV Advertisement Consent LBC Listed Building Consent CC3RE G County Council Regulation 3 LBD Listed Building Consent - Demolition CC4RE G County Council Regulation 4 OUT Outline Application CM County Matters RES Reserved Matters Application FUL Full Application S73 Removal or Variation of Condition/s HHD Householder Application POB Discharge of Planning Obligation/s CLP Certificate of Lawfulness Proposed CLE Certificate of Lawfulness Existing CLASS Change of Use – Agriculture to CND Discharge of Conditions M Commercial PDET28 Agricultural Prior Approval Hazardous Substances Application PN56 Change of Use Agriculture to Dwelling HAZ Householder Application under POROW Creation or Diversion of Right of Way PN42 Permitted Development legislation. TCA Works to Trees in a Conservation Area Telecoms Prior Approval TPO Works to Trees subject of a Tree PNT Non Material Amendment Preservation Order NMA Withdrawn FDO Finally Disposed Of WDN Decisio Description Decisio Description n Code n Code APP Approve RNO Raise no objection REF Refuse ROB Raise Objection P1REQ Prior Approval Required P2NRQ Prior Approval Not Required P3APP Prior Approval Approved P3REF Prior Approval Refused P4APP Prior Approval Approved P4REF Prior Approval Refused West Oxfordshire District Council – DELEGATED ITEMS Week Ending 26th February 2021 Application Number. Ward. Decision. 1. 19/03436/FUL Bampton and Clanfield APP Installation of an Equine Training Area/Manege Land At Cobfield Aston Road Bampton Mr And Mrs Will And Sharon Hicks DELGAT 2. 20/01655/FUL Ducklington REF Erection of four new dwellings and associated works (AMENDED PLANS) Land West Of Glebe Cottage Lew Road Curbridge Mr W Povey, Mr And Mrs C And J Mitchel And Abbeymill Homes L 3. -

Town and Country Planning Acts Require the Following to Be Advertised 17/01394/FUL BRIZE NORTON DEP CONLB MAJ PROW

WEST OXFORDSHIRE DISTRICT COUNCIL Town and Country Planning Acts require the following to be advertised 17/01394/FUL BRIZE NORTON DEP CONLB MAJ PROW. Land South of Upper Haddon Farm Station Road Brize Norton. 17/01441/HHD SHIPTON UNDER WYCHWOOD CONLB PROW. The Old Beerhouse Simons Lane Shipton Under Wychwood. 17/01442/LBC SHIPTON UNDER WYCHWOOD LBC. The Old Beerhouse Simons Lane Shipton Under Wychwood. 17/01453/HHD WOODSTOCK CONLB. 126 Oxford Street Woodstock Oxfordshire. 17/01337/HHD LITTLE TEW CONLB. Manor House Chipping Norton Road Little Tew. 17/01338/LBC LITTLE TEW LBC. Manor House Chipping Norton Road Little Tew. 17/01392/LBC STANDLAKE LBC. Midway Lancott Lane Brighthampton. 17/01395/HHD DUCKLINGTON CONLB. 3 The Square Ducklington Witney. 17/01450/S73 GREAT TEW CONLB. Land at the Great Tew Estate Great Tew Oxfordshire. 17/01482/HHD FULBROOK PROW. Appledore Garnes Lane Fulbrook. 17/01627/HHD HAILEY CONLB PROW. 1 Middletown Cottages Middletown Hailey. 17/01332/HHD BAMPTON PROW. 5 Mercury Court Bampton Oxfordshire. 17/01255/FUL WITNEY CONLB. The Old Coach House Marlborough Lane Witney. 17/01397/FUL ALVESCOT CONLB. Rock Cottage Main Road Alvescot. 17/01406/HHD FILKINS AND BROUGHTON POGGS CONLB. Broctun House Broughton Poggs Lechlade. 17/01399/FUL CHASTLETON CONLB. School Kitebrook House Little Compton. 17/01409/HHD BRIZE NORTON CONLB. Yew Tree Cottage 60 Station Road Brize Norton. 17/01410/LBC BRIZE NORTON LBC. Yew Tree Cottage 60 Station Road Brize Norton. 17/01423/LBC ASCOTT UNDER WYCHWOOD LBC. The Old Farmhouse 15 High Street Ascott Under Wychwood. 17/01214/FUL WITNEY PROW. Cannon Pool Service Station 92 Hailey Road Witney. -

Discover the Lower Windrush Valley

Walks Key Walks TL Turn Left Windrush Path, Standlake to Newbridge Sites of interest Leisure & Walks TR Turn Right Valley Windrush Length: Approx 1.7 miles / 2.8 km If you are driving to a walk start point, please FL Fork Left Time: 40 minutes Dix Pit lake is a Local Wildlife Site and is ensure that you park respectfully, especially in FR Fork Right important because of the lack of disturbance, Lower the village locations. Start point: Standlake the presence of shallow areas and islands and BL Bear Left End Point: Newbridge is particularly good for terns, ducks, grebes Witney Lake BR Bear Right and gulls. Discover Gill Mill Circular Walk 1. From Black Horse Pub in Standlake Stanton Harcourt Archeological digs here between 1990 and Stanton Harcourt is a small, pretty village Length: Approx 5 miles / 8 km cross the main road to 1999 resulted in approximately 1500 bones dating from the Bronze Age. Rich in history, Time: 1 hour 45 minutes Shifford Lane. Follow and teeth from large animals being excavated. the village has been a focus for archaeologists The remains belonged to a range of species Start and end point: Rushy Common Car Park Shifford Lane past STANDLAKE for many years including the Channel 4 the Maybush School including mammoth, elephant, horse, bear programme ‘Time Team’. Stanton Harcourt 1. TL out of Rushy Common until you reach a and lion. Manor House is well-known for its 14th car park and walk 2 crossroads. 1 century medieval kitchens - the most complete Devil’s Quoits approximately 100 metres surviving medieval kitchens in the country. -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

Early Medieval Oxfordshire

Anglo-Saxon Oxfordshire Sally Crawford and Anne Dodd, December 2007 1. Introduction: nature of the evidence, history of research and the role of material culture Anglo-Saxon Oxfordshire has been extremely well served by archaeological research, not least because of coincidence of Oxfordshire’s diverse underlying geology and the presence of the University of Oxford. Successive generations of geologists at Oxford studied and analysed the landscape of Oxfordshire, and in so doing, laid the foundations for the new discipline of archaeology. As early as 1677, geologist Robert Plot had published his The Natural History of Oxfordshire ; William Smith (1769- 1839), who was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire, determined the law of superposition of strata, and in so doing formulated the principles of stratigraphy used by archaeologists and geologists alike; and William Buckland (1784-1856) conducted experimental archaeology on mammoth bones, and recognised the first human prehistoric skeleton. Antiquarian interest in Oxfordshire lead to a number of significant discoveries: John Akerman and Stephen Stone's researches in the gravels at Standlake recorded Anglo-Saxon graves, and Stone also recognised and plotted cropmarks in his local area from the back of his horse (Akerman and Stone 1858; Stone 1859; Brown 1973). Although Oxford did not have an undergraduate degree in Archaeology until the 1990s, the Oxford University Archaeological Society, originally the Oxford University Brass Rubbing Society, was founded in the 1890s, and was responsible for a large number of small but significant excavations in and around Oxfordshire as well as providing a training ground for many British archaeologists. Pioneering work in aerial photography was carried out on the Oxfordshire gravels by Major Allen in the 1930s, and Edwin Thurlow Leeds, based at the Ashmolean Museum, carried out excavations at Sutton Courtenay, identifying Anglo-Saxon settlement in the 1920s, and at Abingdon, identifying a major early Anglo-Saxon cemetery (Leeds 1923, 1927, 1947; Leeds 1936). -

Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2016 Butchered Bones, Carved Stones: Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England Shawn Hale Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in History at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Hale, Shawn, "Butchered Bones, Carved Stones: Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England" (2016). Masters Theses. 2418. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2418 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Graduate School� EASTERNILLINOIS UNIVERSITY " Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate Candidates Completing Theses in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, and Distribution of Thesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth Library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for-profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. Your signatures affirm the following: • The graduate candidate is the author of this thesis. • The graduate candidate retains the copyright and intellectual property rights associated with the original research, creative activity, and intellectual or artistic content of the thesis. -

Cberfseg Q& Bbeg a Gxizfence of Be Past

CBerfseg Q&BBeg G i fen o { e a x z ce f B (past. B Y W L U C Y H E E L E R . ' I/Vzt fi Pr qfac e by S IR W N FE N S I EADY . T A B B Y H R ’ ‘ ARMS 09 T HE MON AS T E RY OF S . PE E R, E C U C H, C HE R I S EY . Eonb on D. W E LL GARDN E R DARTON c o . LT S , , , Pat r n s r i ldi n a V r i a t r t W B u s E n d i c t o S e e S . e o te C. 3 , g , , 44, , PREFAC E THE History of Chertsey Abbey is of more than loc al interest . Its foundation carries us back to so remote a fi x e d period that the date is uncertain . The exact date i i AD 6 66 from n the Chertsey register s . but Reyner, ’ ’ Ca rave s Li e o S . E r ke n wala wi p g f f , ll have this Abbey D 6 0 . to have been founded as early as A. 3 That Erken wa d u e l , however, was the real fo nder, and before he b came s Bishop of London , admit of no doubt . Even the time ’ Erke n wald s c ac i i of death is not ertain , some p l ng it n w Hi 6 8 h i e i 6 .