Richard Lovell Edgeworth a Selection from His Memoirs Edited by Beatrix L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anna Seward and the Poetics of Sensibility and Control Andrew O

Criticism Volume 58 | Issue 2 Article 9 2016 Anna Seward and the Poetics of Sensibility and Control Andrew O. Winckles Adrian College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/criticism Recommended Citation Winckles, Andrew O. (2016) "Anna Seward and the Poetics of Sensibility and Control," Criticism: Vol. 58 : Iss. 2 , Article 9. Available at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/criticism/vol58/iss2/9 ANNA SEWARD At the 2011 meeting of the North American Society for the Study AND THE POETICS of Romanticism, Anne K. Mellor OF SENSIBILITY reflected on how the field has AND CONTROL changed since her foundational Andrew O. Winckles 1993 study Romanticism and Gender. She commented that, though women writers such as Anna Seward and the End of the Mary Wollstonecraft, Jane Austen, Eighteenth Century by Claudia and Mary Shelley have cemented Thomas Kairoff. Baltimore, MD: themselves as legitimate objects Johns Hopkins University Press, of study, this has largely been at 2012. Pp. 328. $58 cloth. the expense of a broader under- standing of how women writers were working during the period. In addition to the Big Six male Romantics, we have in many cases simply added the Big Three female Romantics.1 Though this has begun to change in the last ten years, with important studies appearing about women like Anna Letitia Barbauld, Mary Robinson, Joanna Baillie, and Hannah More, we still know shockingly little about women writers’ lives, cultural con- texts, and works. A case in point is Anna Seward, a poet and critic well known and respected in her own lifetime, but whose critical neglect in the nineteenth and twentieth centu- ries has largely shaped how recent critics interact with her work. -

The Perfect Wife”

“THE PERFECT WIFE” BY RACHAEL CARNES ESTIMATED RUNNING TIME — 90 MINUTES CAST — SIX PERFORMERS Rachael Carnes, member: Dramatists Guild, National New Play Network, Playwrights Center, AWP 1050 W 17th Ave, Eugene OR 97402, 541-221-5792 www.rachaelcarnes.com [email protected] © 2017, All Rights Reserved. SUMMARY As revolution between England and its American colonies simmers, candy-colored Georgian society pits the woeful, starving masses against the excessive powers of the rich elite. One bright young man, Sir Thomas Day, rebuffed at every turn from would- be wives, despite his fortune, grows frustrated, and hatches a plan to steal an orphan, and raise her to be the Perfect Wife. Based on real events, this work of historical fiction opens in the Shrewsbury Foundling Hospital, with Day on the hunt. CHARACTERS Thomas Day A tall, dark-haired, pock-marked man of 21, disheveled, with stringy, matted long hair, dirty fingernails and drab, misshapen and fraying, but expensive, clothes. Sabrina (Anne) An “orphaned” girl, 12 years old, red-haired, freckled, dressed in a rough-hewn smock and no shoes. DUAL ROLES (MAN) Richard Etheridge A wealthy Irish inventor of useless mechanicals and Day’s foppish friend, a few years his elder, powdered and be- wigged, spritely as a grasshopper, he dresses in the au courante dandy Georgian men’s style — trussed in a corset, with fat, padded calves and a stuffed chest. Ferry Master Middle-aged, muscular, he wears a threadbare, high-cut sailor’s uniform, heavy black fisherman’s shoes and a wide, flat black hat over a dusty white bonnet. -

The Adventurous History of Sabrina Sidney

CONSTRUCTING THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY WOMAN: THE ADVENTUROUS HISTORY OF SABRINA SIDNEY By KATHARINE ILES A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham April 2012 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The story of Thomas Day’s attempt to educate a young girl according to the theories of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, with the aim of marrying her, has often been referred to as a footnote in Enlightenment history. However, the girl chosen by Day, Sabrina Sidney, has never been placed at the centre of any historical enquiry, nor has the experiment been explored in any depth. This study places Sabrina at its centre to investigate its impact on her and to examine the intellectual and societal debates that informed Thomas Day’s decision to educate a wife. This thesis argues that Sabrina Sidney was in a constant state of construction, which changed depending on a myriad of factors and that constructions of her were fluid and flexible. -

Historical Group Occasional Paper 8

‘the first example … of an extensive scheme of pure scientific medical investigation’: Thomas Beddoes and the Medical Pneumatic Institution in Bristol, 1794 to 1799 Frank A.J.L. James Department of Science and Technology Studies, University College London, Gower Street, London, WC1E 6BT, England Royal Institution, 21 Albemarle Street, London, W1S 4BS, England [email protected] The Eighth Wheeler Lecture Royal Institution, 12 October 2015 RSCHG Occasional Paper No. 8, published November 2016 ISBN: 2050-0424 Series Editor: Dr Anna Simmons ORCID identification number (http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0499-9291) Acknowledgements I thank the following archives for permission to study manuscripts and other documents in their collections: Library of Birmingham (LoB), Cornwall Record Office (CRO), Wedgwood Museum (WM), The National Archives (TNA), Bristol Record Office (BRO), British Library (BL), National Library of Ireland (NLI), Bedfordshire and Luton Archive Service (BALAS), the Royal Institution (RI), Natural History Museum (NHM), the Royal Society of London, the Linnean Society, Bristol Central Library, McGill University, Chatsworth, Lambton Park and the Bodleian Library. Letters written by Humphry Davy are freely available on-line at <www.davy-letters.org.uk> as part of the project to publish them by the end of the decade. In the meantime, this paper cites their archival or printed locations. I thank the Research Group of the STS Department at University College London for many valuable comments on an earlier draft. Note to Readers Because of the tendency of the Wedgwood, Watt and Boulton families to use the same forenames in succeeding generations, both the fore and surnames of correspondents are given consistently in the notes. -

The Concept of Child Before Progressive Education

1 Prof. Dr. Jürgen Oelkers University of Zurich Freiestrasse 36 CH-8032 +41 44 634 25 92 [email protected] The Concept of Child before Progressive Education Children cannot be “discovered”—they have always existed. Nevertheless, one can speak of a “pedagogical discovery of the child.” Prior to the eighteenth century, children re- ceived little attention in society and were considered, if anything, an object to be schooled. They were of interest to religion and the church, to the family as labor power, and to the so- cial class to which they belonged from birth, but they were not considered in their own right or on their own terms. The resulting neglect of children’s education is clearly demonstrated by two indicators: the level of literacy, and the legal status of the child. In the European Middle Ages, only the Jews could claim a high level of literacy, since the boys had to learn to read and write Hebrew to understand the Torah. As late as the early eighteenth century, two-thirds of the French population was still illiterate and could neither read nor write. Even in the mid-nineteenth century, one-third of all English men and almost half of English women had to sign official documents such as marriage and baptism certifi- cates with an “X” because they were illiterate. The first law mandating compulsory education in England and Wales was passed in 1870. Before that time, the government invested nothing in public education. At the time of the American Revolution, however, 90 percent of the pop- ulation of New England was literate because of the instruction provided by Puritan churches. -

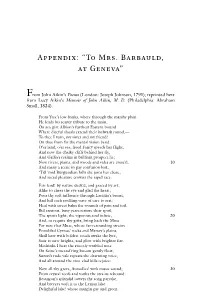

Appendix: “To Mrs. Barbauld, at Geneva”

Appendix: “To Mrs. Barbauld, at Geneva” From John Aikin’s Poems (London: Joseph Johnson, 1791); reprinted here from Lucy Aikin’s Memoir of John Aikin, M. D. (Philadelphia: Abraham Small, 1824). From Yare’s low banks, where through the marshy plain He leads his scanty tribute to the main, On sea-girt Albion’s furthest Eastern bound Where direful shoals extend their bulwark round,— To thee I turn, my sister and my friend! On thee from far the mental vision bend. O’er land, o’er sea, freed Fancy speeds her flight, And now the chalky cliffs behind her fly, And Gallia’s realms in brilliant prospect lie; Now rivers, plains, and woods and vales are cross’d, 10 And many a scene in gay confusion lost, ’Till ’mid Burgundian hills she joins her chase, And social pleasure crowns the rapid race. Fair land! by nature deck’d, and graced by art, Alike to cheer the eye and glad the heart, Pour thy soft influence through Laetitia’s breast, And lull each swelling wave of care to rest; Heal with sweet balm the wounds of pain and toil, Bid anxious, busy years restore their spoil; The spirits light, the vigorous soul infuse, 20 And, to requite thy gifts, bring back the Muse. For sure that Muse, whose far-resounding strains Ennobled Cyrnus’ rocks and Mersey’s plains, Shall here with boldest touch awake the lyre, Soar to new heights, and glow with brighter fire. Methinks I hear the sweetly-warbled note On Seine’s meand’ring bosom gently float; Suzon’s rude vale repeats the charming voice, And all around the vine-clad hills rejoice: Now all thy grots, Auxcelles! with music sound; 30 From crystal roofs and vaults the strains rebound: Besançon’s splendid towers the song partake, And breezes waft it to the Leman lake. -

Maria Edgeworth | Practical Education | Harper, 1855 | 1855

Maria Edgeworth | Practical Education | Harper, 1855 | 1855 Practical Education Practical Education, Volume 2 Practical Education, Volume 1 Leonora. Ennui Tales, and Miscellaneous Pieces, Volume 4 Memoirs of Richard Lovell Edgeworth, Esq, Volumes 1- 2 What is practical education? Update Cancel. ad by Quora for Business. Want to convert educational intent into business? Use Quora Ads to promote your business alongside topics like career or school advice. Learn More at quora.com. Education which teaches you literally on how to HANDLE things properly and to good use. 576 Views · Answer requested by. Kunal Pandhram. Related Questions. Should education be practical or theoretical? What are the benefits of practical education? Practical Education is an educational treatise written by Maria Edgeworth and her father Richard Lovell Edgeworth. Published in 1798, it is a comprehensive theory of education that combines the ideas of philosophers John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau as well as of educational writers such as Thomas Day, William Godwin, Joseph Priestley, and Catharine Macaulay. The Edgeworths' theory of education was based on the premise that a child's early experiences are formative and that the associations they Practical Education's wiki: Practical Education is an educational treatise written by Honora Sneyd, her step-daughter Maria Edgeworth and her husband Richard Lovell Edgeworth. Sneyd died before she could complete it. Reference Links For This Wiki. All information for Practical Education's wiki comes from the below links. Any source is valid, including Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn. Pictures, videos, biodata, and files relating to Practical Education are also acceptable encyclopedic sources. -

Maria Edgeworth - a Biographical Note

Published on Great Writers Inspire (http://writersinspire.org) Home > Maria Edgeworth - A biographical note. Maria Edgeworth - A biographical note. Maria Edgeworth (1768-1849). A Biographical Note Maria Edgeworth was the third child and eldest daughter of Richard Lovell Edgeworth (1744-1817) and his first wife, Anna Maria Elers (1743-1777). Richard Lovell Edgeworth was an Anglo-Irish politician, writer and inventor and a leading light of the Birmingham Lunar Society (founded in the 1770s). Maria was born at Black Bourton, Oxfordshire on 1 January 1768. Her mother died of puerperal fever following the birth of a fifth child in March 1773 and her father swiftly remarried only three months later to Honora Sneyd of Lichfield (1751-1780). Maria went with her surviving brother and two sisters to live with her father at the family estate at Edgeworthstown, County Longford briefly before she was sent away to a boarding school in England. She returned to Edgeworthstown in the summer of 1782 by which time her stepmother had died (1780) and her father married again, this time to Elizabeth Sneyd, the sister of his late wife. Maria now formed a strong bond with her father and participated in educating his ever growing family of children as well as managing the estate. Her first published works were Letters for Literary Ladies in 1795 ? which made a vigorous case for female rationality and skills as writers and a collection of children?s stories (The Parent?s Assistant, 1796, but it was Practical Education of 1798, co-authored with her father, that propelled Maria Edgeworth to international fame. -

Anna Seward (1742-1809) by Marion Roberts

Anna Seward (1742-1809) by Marion Roberts The eighteenth century was a competitive world, progress being made by the money you had or the notice you attracted; with whom you mixed and to whose gatherings you were invited; how much influence you had and how many connections you made. All these were of much concern. You needed to understand the rules of social rank and have a respect for wealth. Being female in a society which valued female dependency was difficult, but could sometimes be turned to advantage. Women’s lives seemed to be a progress of various milestones: maiden, wife, mother, and, if she was unlucky, widow, dowager and grandmother. At each stage, women were expected to bow to the will of providence and do their duty. For Anna Seward to be mistress of herself was paramount: to be self-possessed, self-controlled and self- sufficient, brave and enduring in the face of misfortune. She turned her back on the institution of marriage, which she blamed for her misfortunes and despite several proposals, resolved to lead a quiet, spinster life. But as Robert Burns would write: ‘The best laid schemes of mice and men/ Gang aft a-gley ’. Anna Seward was born in 1742 in the Plague village of Eyam, in the Derbyshire hills, where her father, the Rev. Thomas Seward, was minister. A redheaded, precocious, sensitive child, she could recite Milton at the age of three. She was greatly attached to her younger sister, Sarah. Sarah died, aged nineteen, from an ‘unspecified fever’ (possibly Miliary Tuberculosis) just before her arranged marriage to Joseph Porter. -

The Anti-Slavery Debate: the Clapham Sect, the Lunar Society

The Anti-Slavery Debate Around Lichfield Anna Seward, the Clapham Sect, the Lunar Society, Yoxall Lodge and Kings Bromley The area around Lichfield was the scene for intense arguments at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries. On the one hand, families such as the Newtons of Kings Bromley and, after 1794, the Lanes of Kings Bromley were slave owners and therefore anti-abolitionists. On the other hand groups such as the Clapham Sect, which included William Wilberforce and Thomas Gisborne of Yoxall Lodge, and the Lunar Society which included Erasmus Darwin and, on its fringes, Anna Seward of Lichfield were abolitionists. Some people's acquaintance spanned both groups. The Lanes' cousin, William Legge, second Earl of Dartmouth (1731–1801), was a member of the Clapham Sect. Anna Seward knew the Newtons of Kings Bromley, and was very friendly with the Ardens of Longcroft, Yoxall, particularly with the daughters Anne and Althea Catherina, who are mentioned in the trial of Catherine Newton (see KBH publication 'The Scandalous Divorce of John Newton') The Arden sisters' two brothers John and Humphrey were both beneficiaries of Catherine Newton's will (see KBH publication 'The Lane Inheritance') and John was vicar of Kings Bromley from 1782-1800. Anna Seward, the 'Swan of Lichfield' was a poet, perhaps now best known for her collected letters and her Memoirs of the Life of Dr. Darwin. Anna Seward by Tilly Kettle in 1762 Born in Derbyshire in 1742, her father undertook her education and Anna developed her literary tastes at an early age, reading Milton at two and writing religious verse at ten. -

The Electronic Version of This Text Has Been Created As a Part of The

The electronic version of this text has been created as a part of the "Publishing in Irish America: 1820-1922" project that is being undertaken by the CUNY Institute for Irish-American Studies, Center for the Preservation of Irish-American Publications. Project: Publishing in IA Date Created: 08/23/07 ObjectlD: 00000143 Object Name: Maria Edgeworth Life & Lellers I Author: Augustus J.e. Hare. ed. Dale Published: 1895 Publisher: Houghton. Mimin & Co. Donor: City College Library Funding: Metropolitan New York Library Council l,JRRARY TIHC~;COLLElGE OJo' TJ:CE C11I''T OF ITE'W -irD.RJK THE LIFE AND LETTERS OF MARIA EDGEWORTH EDITED BY AUGUSTUSJ.C.HARE AUTHOR OF "MEMORIALS OF A QUIET LIFE," H THE STORY OF TWO NOBLE LIVES" IN TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I. BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AXD CO:\IPANY ~be lliu£tSibe ll're!i;, i/I:ambrJblle 1895 Copyright, 1894, By HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN & CO. All rights reserved. The River.ride Pres .•, Cambridge, flEaS3., U. S. A. Electrotyped and Printed hy H. O. Houghton and Company • .. PREFACE IN her later years Miss Edgeworth was often asked to write a biographical preface to her novels. She refused. "As a woman," she said, "my life, whoIly domestic, can offer nothing of interest to the public." Incidents indeed, in that quiet happy home existence, there were none to narrate, nothing but the ordinary joys and sor- rows which attend every human life. Yet the letters of one so clear - sighted and sagacious - one whom Macaulay comidered to be the second woman of her age - are valuable, not only as a record of her times, and of many who were prominent figures in them, but from the picture they naturally give of a simple, honest, gen- erous, high-minded character, filled from youth to age with love and goodwill to her feIlow-creatures, and a desire for their highest good. -

22 Maria Edgeworth.Pdf

cl11aria {)igevvorth (1768-1849) In his 1829 preface to Waverley, Walter Scott acknowledges his considerable debt to the artistry of Maria Edgeworth, author of the innovative novel Castle Rackrent (1800): "Without being so presumptuous as to hope to emulate the rich humour, pathetic tenderness, and admirable tact which pervade the works of my accomplished friend, I felt that something might be attempted for my own country, of the same kind with that which Miss Edgeworth so fortunately achieved for Ireland." Lord Byron recalled in 1813, "I had been the lion of 1812: Miss Edgeworth and Madame de Stael ... were the ex hibitions of the succeeding year." 1 Author of Belinda, Leonora, Patronage, and other novels and tales, Edgeworth was one of the most respected educational writers and novelists of the age. Moreover, her tales for children, informed by Enlightenment educational theory and shaped by her role as surrogate mother to her many younger siblings, were popular and influential. Born at Black Bourton, Oxfordshire, on 1 January 1768, Maria was the second surviving child and eldest daughter of Anna Maria Elers and Richard Lovell Edgeworth, an Anglo-Irish landowner, educational theorist, scien tist, and author. Maria Edgeworth's mother died in childbirth in 1773, and Maria grew up adoring and emulating her father, who married four times altogether, eventually producing twenty-two children, eighteen of whom survived infancy.2 His second wife, Honora Sneyd, was the foster sister of Anna Seward. Maria Edgeworth grew up on Anna Letitia Barbauld's Lessons for Children and attended boarding schools in England, where she received conventional instruction.