Historical Group Occasional Paper 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Withering and the Introduction of Digitalis Into Medical Practice

[From Schenckius: Observationum Medicarum, Francofurti, 1609.] ANNALS OF MEDICAL HISTORY New Series , Volume VIII May , 1936 Numbe r 3 WILLIAM WITHERING AND THE INTRODUCTION OF DIGITALIS INTO MEDICAL PRACTICE By LOUIS H. RODDIS, COMMANDER, M.C., U.S.N. WASHINGTON, D. C. Part II* N interesting fea- as Dr. Fulton points out, there is no ture regarding the question that Darwin received his first early use of digi- acquaintancewithdigitalis from Wither- talis and the ques- ing. The evidence is indisputable as tion of the priority Withering himself cites the case (No. of Withering in its iv, M iss Hill) and says that Darwin was discovery, has been his consultant. Darwin mentions the brought out by case in his commonplace book but Professor John F. Fulton of Yale Uni- neither there nor in his published ac- versity School of Medicine. He has counts does he mention Withering’s shown that Erasmus Darwin, in an ap- name. His relations with Withering are pendix to the graduation thesis of his shown by some of his letters to have son Charles, which he published in been very unfriendly, at least after 1780, two years after Charles’ death. 1788, and he was probably jealous of gave some account of the use of fox- him. By our present standards Darwin’s glove with several case histories. March conduct in not mentioning Withering 16. 1785, Erasmus Darwin read a paper in either of his papers was distinctly which was dated January 14, 1785, and uncthical. which was published in the medical As he became more prosperous With- transactions, containing a reference to ering purchased a valuable piece of foxglove. -

The Lunar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in 18Th Century Great Britain

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2011 The unL ar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in 18th Century Great Britain Scott H. Zurawel Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Zurawel, Scott H., "The unL ar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in 18th Century Great Britain" (2011). Honors Theses. 1092. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/1092 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i THE LUNAR SOCIETY OF BIRMINGHAM AND THE PRACTICE OF SCIENCE IN 18TH CENTURY GREAT BRITAIN: A STUDY OF JOSPEH PRIESTLEY, JAMES WATT AND WILLIAM WITHERING By Scott Henry Zurawel ******* Submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for Honors in the Department of History UNION COLLEGE March, 2011 ii ABSTRACT Zurawel, Scott The Lunar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in Eighteenth-Century Great Britain: A Study of Joseph Priestley, James Watt, and William Withering This thesis examines the scientific and technological advancements facilitated by members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham in eighteenth-century Britain. The study relies on a number of primary sources, which range from the regular correspondence of its members to their various published scientific works. The secondary sources used for this project range from comprehensive books about the society as a whole to sources concentrating on particular members. -

Twenty-Four Conservative-Liberal Thinkers Part I Hannes H

Hannes H. Gissurarson Twenty-Four Conservative-Liberal Thinkers Part I Hannes H. Gissurarson Twenty-Four Conservative-Liberal Thinkers Part I New Direction MMXX CONTENTS Hannes H. Gissurarson is Professor of Politics at the University of Iceland and Director of Research at RNH, the Icelandic Research Centre for Innovation and Economic Growth. The author of several books in Icelandic, English and Swedish, he has been on the governing boards of the Central Bank of Iceland and the Mont Pelerin Society and a Visiting Scholar at Stanford, UCLA, LUISS, George Mason and other universities. He holds a D.Phil. in Politics from Oxford University and a B.A. and an M.A. in History and Philosophy from the University of Iceland. Introduction 7 Snorri Sturluson (1179–1241) 13 St. Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) 35 John Locke (1632–1704) 57 David Hume (1711–1776) 83 Adam Smith (1723–1790) 103 Edmund Burke (1729–1797) 129 Founded by Margaret Thatcher in 2009 as the intellectual Anders Chydenius (1729–1803) 163 hub of European Conservatism, New Direction has established academic networks across Europe and research Benjamin Constant (1767–1830) 185 partnerships throughout the world. Frédéric Bastiat (1801–1850) 215 Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–1859) 243 Herbert Spencer (1820–1903) 281 New Direction is registered in Belgium as a not-for-profit organisation and is partly funded by the European Parliament. Registered Office: Rue du Trône, 4, 1000 Brussels, Belgium President: Tomasz Poręba MEP Executive Director: Witold de Chevilly Lord Acton (1834–1902) 313 The European Parliament and New Direction assume no responsibility for the opinions expressed in this publication. -

Anna Seward and the Poetics of Sensibility and Control Andrew O

Criticism Volume 58 | Issue 2 Article 9 2016 Anna Seward and the Poetics of Sensibility and Control Andrew O. Winckles Adrian College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/criticism Recommended Citation Winckles, Andrew O. (2016) "Anna Seward and the Poetics of Sensibility and Control," Criticism: Vol. 58 : Iss. 2 , Article 9. Available at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/criticism/vol58/iss2/9 ANNA SEWARD At the 2011 meeting of the North American Society for the Study AND THE POETICS of Romanticism, Anne K. Mellor OF SENSIBILITY reflected on how the field has AND CONTROL changed since her foundational Andrew O. Winckles 1993 study Romanticism and Gender. She commented that, though women writers such as Anna Seward and the End of the Mary Wollstonecraft, Jane Austen, Eighteenth Century by Claudia and Mary Shelley have cemented Thomas Kairoff. Baltimore, MD: themselves as legitimate objects Johns Hopkins University Press, of study, this has largely been at 2012. Pp. 328. $58 cloth. the expense of a broader under- standing of how women writers were working during the period. In addition to the Big Six male Romantics, we have in many cases simply added the Big Three female Romantics.1 Though this has begun to change in the last ten years, with important studies appearing about women like Anna Letitia Barbauld, Mary Robinson, Joanna Baillie, and Hannah More, we still know shockingly little about women writers’ lives, cultural con- texts, and works. A case in point is Anna Seward, a poet and critic well known and respected in her own lifetime, but whose critical neglect in the nineteenth and twentieth centu- ries has largely shaped how recent critics interact with her work. -

Soho Depicted: Prints, Drawings and Watercolours of Matthew Boulton, His Manufactory and Estate, 1760-1809

SOHO DEPICTED: PRINTS, DRAWINGS AND WATERCOLOURS OF MATTHEW BOULTON, HIS MANUFACTORY AND ESTATE, 1760-1809 by VALERIE ANN LOGGIE A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History of Art College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham January 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis explores the ways in which the industrialist Matthew Boulton (1728-1809) used images of his manufactory and of himself to help develop what would now be considered a ‘brand’. The argument draws heavily on archival research into the commissioning process, authorship and reception of these depictions. Such information is rarely available when studying prints and allows consideration of these images in a new light but also contributes to a wider debate on British eighteenth-century print culture. The first chapter argues that Boulton used images to convey messages about the output of his businesses, to draw together a diverse range of products and associate them with one site. Chapter two explores the setting of the manufactory and the surrounding estate, outlining Boulton’s motivation for creating the parkland and considering the ways in which it was depicted. -

Teaching Eighteenth-Century French Literature: the Good, the Bad and the Ugly

Eighteenth-Century Modernities: Present Contributions and Potential Future Projects from EC/ASECS (The 2014 EC/ASECS Presidential Address) by Christine Clark-Evans It never occurred to me in my research, writing, and musings that there would be two hit, cable television programs centered in space, time, and mythic cultural metanarrative about 18th-century America, focusing on the 1760s through the 1770s, before the U.S. became the U.S. One program, Sleepy Hollow on the FOX channel (not the 1999 Johnny Depp film) represents a pre- Revolutionary supernatural war drama in which the characters have 21st-century social, moral, and family crises. Added for good measure to several threads very similar to Washington Irving’s “Legend of Sleepy Hollow” story are a ferocious headless horseman, representing all that is evil in the form of a grotesque decapitated man-demon, who is determined to destroy the tall, handsome, newly reawakened Rip-Van-Winkle-like Ichabod Crane and the lethal, FBI-trained, diminutive beauty Lt. Abigail Mills. These last two are soldiers for the politically and spiritually righteous in both worlds, who themselves are fatefully inseparable as the only witnesses/defenders against apocalyptic doom. While the main characters in Sleepy Hollow on television act out their protracted, violent conflict against natural and supernatural forces, they also have their own high production-level, R & B-laced, online music video entitled “Ghost.” The throaty feminine voice rocks back and forth to accompany the deft montage of dramatic and frightening scenes of these talented, beautiful men and these talented, beautiful women, who use as their weapons American patriotism, religious faith, science, and wizardry. -

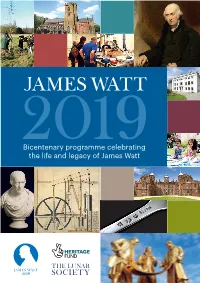

Bicentenary Programme Celebrating the Life and Legacy of James Watt

Bicentenary programme celebrating the life and legacy of James Watt 2019 marks the 200th anniversary of the death of the steam engineer James Watt (1736-1819), one of the most important historic figures connected with Birmingham and the Midlands. Born in Greenock in Scotland in 1736, Watt moved to Birmingham in 1774 to enter into a partnership with the metalware manufacturer Matthew Boulton. The Boulton & Watt steam engine was to become, quite literally, one of the drivers of the Industrial Revolution in Britain and around the world. Although best known for his steam engine work, Watt was a man of many other talents. At the start of his career he worked as both a mathematical instrument maker and a civil engineer. In 1780 he invented the first reliable document copier. He was also a talented chemist who was jointly responsible for proving that water is a compound rather than an element. He was a member of the famous Lunar Portrait of James Watt by Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1812 Society of Birmingham, along with other Photo by Birmingham Museums Trust leading thinkers such as Matthew Boulton, Erasmus Darwin, Joseph Priestley and The 2019 James Watt Bicentenary Josiah Wedgwood. commemorative programme is The Boulton & Watt steam engine business coordinated by the Lunar Society. was highly successful and Watt became a We are delighted to be able to offer wealthy man. In 1790 he built a new house, a wide-ranging programme of events Heathfield Hall in Handsworth (demolished and activities in partnership with a in 1927). host of other Birmingham organisations. Following his retirement in 1800 he continued to develop new inventions For more information about the in his workshop at Heathfield. -

5. the Lives of Two Pioneering Medical Chemists.Indd

The West of England Medical Journal Vol 116 No 4 Article 2 Bristol Medico-Historical Society Proceedings The Lives of Two Pioneering Medical-Chemists in Bristol Thomas Beddoes (1760-1808) and William Herapath (1796-1868) Brian Vincent School of Chemistry, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1TS. Presented at the meeting on Dec 12th 2016 ABSTRACT From the second half of the 18th century onwards the new science of chemistry took root and applications were heralded in many medical-related fields, e.g. cures for diseases such as TB, the prevention of epidemics like cholera, the application of anaesthetics and the detection of poisons in forensics. Two pioneering chemists who worked in the city were Thomas Beddoes, who founded the Pneumatic Institution in Hotwells in 1793, and William Herapath who was the first professor of chemistry and toxicology at the Bristol Medical School, located near the Infirmary, which opened in 1828. As well as their major contributions to medical-chemistry, both men played important roles in the political life of the city. INTRODUCTION The second half of the 18th century saw chemistry emerge as a fledgling science. Up till then there was little understanding of the true nature of matter. The 1 The West of England Medical Journal Vol 116 No 4 Article 2 Bristol Medico-Historical Society Proceedings classical Greek idea that matter consisted of four basic elements (earth, fire, water and air) still held sway, as did the practice of alchemy: the search for the “elixir of life” and for the “philosophers’ stone” which would turn base metals into gold. -

The Many Panics of 1837 People, Politics, and the Creation of a Transatlantic Financial Crisis

The Many Panics of 1837 People, Politics, and the Creation of a Transatlantic Financial Crisis In the spring of 1837, people panicked as financial and economic uncer- tainty spread within and between New York, New Orleans, and London. Although the period of panic would dramatically influence political, cultural, and social history, those who panicked sought to erase from history their experiences of one of America’s worst early financial crises. The Many Panics of 1837 reconstructs the period between March and May 1837 in order to make arguments about the national boundaries of history, the role of information in the economy, the personal and local nature of national and international events, the origins and dissemination of economic ideas, and most importantly, what actually happened in 1837. This riveting transatlantic cultural history, based on archival research on two continents, reveals how people transformed their experiences of financial crisis into the “Panic of 1837,” a single event that would serve as a turning point in American history and an early inspiration for business cycle theory. Jessica M. Lepler is an assistant professor of history at the University of New Hampshire. The Society of American Historians awarded her Brandeis University doctoral dissertation, “1837: Anatomy of a Panic,” the 2008 Allan Nevins Prize. She has been the recipient of a Hench Post-Dissertation Fellowship from the American Antiquarian Society, a Dissertation Fellowship from the Library Company of Philadelphia’s Program in Early American Economy and Society, a John E. Rovensky Dissertation Fellowship in Business History, and a Jacob K. Javits Fellowship from the U.S. -

William Blake 1 William Blake

William Blake 1 William Blake William Blake William Blake in a portrait by Thomas Phillips (1807) Born 28 November 1757 London, England Died 12 August 1827 (aged 69) London, England Occupation Poet, painter, printmaker Genres Visionary, poetry Literary Romanticism movement Notable work(s) Songs of Innocence and of Experience, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, The Four Zoas, Jerusalem, Milton a Poem, And did those feet in ancient time Spouse(s) Catherine Blake (1782–1827) Signature William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his lifetime, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual arts of the Romantic Age. His prophetic poetry has been said to form "what is in proportion to its merits the least read body of poetry in the English language".[1] His visual artistry led one contemporary art critic to proclaim him "far and away the greatest artist Britain has ever produced".[2] In 2002, Blake was placed at number 38 in the BBC's poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.[3] Although he lived in London his entire life except for three years spent in Felpham[4] he produced a diverse and symbolically rich corpus, which embraced the imagination as "the body of God",[5] or "Human existence itself".[6] Considered mad by contemporaries for his idiosyncratic views, Blake is held in high regard by later critics for his expressiveness and creativity, and for the philosophical and mystical undercurrents within his work. His paintings William Blake 2 and poetry have been characterised as part of the Romantic movement and "Pre-Romantic",[7] for its large appearance in the 18th century. -

Biographical Appendix

Biographical Appendix The following women are mentioned in the text and notes. Abney- Hastings, Flora. 1854–1887. Daughter of 1st Baron Donington and Edith Rawdon- Hastings, Countess of Loudon. Married Henry FitzAlan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, 1877. Acheson, Theodosia. 1882–1977. Daughter of 4th Earl of Gosford and Louisa Montagu (daughter of 7th Duke of Manchester and Luise von Alten). Married Hon. Alexander Cadogan, son of 5th Earl of Cadogan, 1912. Her scrapbook of country house visits is in the British Library, Add. 75295. Alten, Luise von. 1832–1911. Daughter of Karl von Alten. Married William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester, 1852. Secondly, married Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, 1892. Grandmother of Alexandra, Mary, and Theodosia Acheson. Annesley, Katherine. c. 1700–1736. Daughter of 3rd Earl of Anglesey and Catherine Darnley (illegitimate daughter of James II and Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester). Married William Phipps, 1718. Apsley, Isabella. Daughter of Sir Allen Apsley. Married Sir William Wentworth in the late seventeenth century. Arbuthnot, Caroline. b. c. 1802. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. She did not marry. Arbuthnot, Marcia. 1804–1878. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. Married William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley, 1825. Aston, Barbara. 1744–1786. Daughter and co- heir of 5th Lord Faston of Forfar. Married Hon. Henry Clifford, son of 3rd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, 1762. Bannister, Henrietta. d. 1796. Daughter of John Bannister. She married Rev. Hon. Brownlow North, son of 1st Earl of Guilford, 1771. Bassett, Anne. Daughter of Sir John Bassett and Honor Grenville. -

Humphry Davy, Nitrous Oxide, the Pneumatic Institution, and the Royal Institution

Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 307: L661–L667, 2014. First published August 29, 2014; doi:10.1152/ajplung.00206.2014. Perspectives Humphry Davy, nitrous oxide, the Pneumatic Institution, and the Royal Institution John B. West Department of Medicine, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, California Submitted 23 July 2014; accepted in final form 18 August 2014 West JB. Humphry Davy, nitrous oxide, the Pneumatic Institu- magnesium, boron, and barium. Davy is also well known as the tion, and the Royal Institution. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Phy- person responsible for developing the miner’s safety lamp. siol 307: L661–L667, 2014. First published August 29, 2014; There is an extensive literature on Davy. A readable intro- doi:10.1152/ajplung.00206.2014.—Humphry Davy (1778–1829) has an duction is Hartley’s (8). The biography by Knight (10) is more interesting place in the history of respiratory gases because the detailed and contains useful citations to primary sources. Tre- Pneumatic Institution in which he did much of his early work signaled neer (17) wrote another biography with an emphasis on Davy’s the end of an era of discovery. The previous 40 years had seen relations with other people including his wife and also Faraday. essentially all of the important respiratory gases described, and the Partington (12) is authoritative on his chemical research. Institution was formed to exploit their possible value in medical Davy’s collected works are available (6). treatment. Davy himself is well known for producing nitrous oxide and demonstrating that its inhalation could cause euphoria and height- Early Years ened imagination.