Cavendish Square

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St Marylebone Parish Church Records of Burials in the Crypt 1817-1853

Record of Bodies Interred in the Crypt of St Marylebone Parish Church 1817-1853 This list of 863 names has been collated from the merger of two paper documents held in the parish office of St Marylebone Church in July 2011. The large vaulted crypt beneath St Marylebone Church was used as place of burial from 1817, the year the church was consecrated, until it was full in 1853, when the entrance to the crypt was bricked up. The first, most comprehensive document is a handwritten list of names, addresses, date of interment, ages and vault numbers, thought to be written in the latter half of the 20th century. This was copied from an earlier, original document, which is now held by London Metropolitan Archives and copies on microfilm at London Metropolitan and Westminster Archives. The second document is a typed list from undertakers Farebrother Funeral Services who removed the coffins from the crypt in 1980 and took them for reburial at Brookwood cemetery, Woking in Surrey. This list provides information taken from details on the coffin and states the name, date of death and age. Many of the coffins were unidentifiable and marked “unknown”. On others the date of death was illegible and only the year has been recorded. Brookwood cemetery records indicate that the reburials took place on 22nd October 1982. There is now a memorial stone to mark the area. Whilst merging the documents as much information as possible from both lists has been recorded. Additional information from the Farebrother Funeral Service lists, not on the original list, including date of death has been recorded in italics under date of interment. -

Unlocking Potential What’S in This Report

Great Portland Estates plc Annual Report 2013 Unlocking potential What’s in this report 1. Overview 3. Financials 1 Who we are 68 Group income statement 2 What we do 68 Group statement of comprehensive income 4 How we deliver shareholder value 69 Group balance sheet 70 Group statement of cash flows 71 Group statement of changes in equity 72 Notes forming part of the Group financial statements 93 Independent auditor’s report 95 Wigmore Street, W1 94 Company balance sheet – UK GAAP See more on pages 16 and 17 95 Notes forming part of the Company financial statements 97 Company independent auditor’s report 2. Annual review 24 Chairman’s statement 4. Governance 25 Our market 100 Corporate governance 28 Valuation 113 Directors’ remuneration report 30 Investment management 128 Report of the directors 32 Development management 132 Directors’ responsibilities statement 34 Asset management 133 Analysis of ordinary shareholdings 36 Financial management 134 Notice of meeting 38 Joint ventures 39 Our financial results 5. Other information 42 Portfolio statistics 43 Our properties 136 Glossary 46 Board of Directors 137 Five year record 48 Our people 138 Financial calendar 52 Risk management 139 Shareholders’ information 56 Our approach to sustainability “Our focused business model and the disciplined execution of our strategic priorities has again delivered property and shareholder returns well ahead of our benchmarks. Martin Scicluna Chairman ” www.gpe.co.uk Great Portland Estates Annual Report 2013 Section 1 Overview Who we are Great Portland Estates is a central London property investment and development company owning over £2.3 billion of real estate. -

Architectural Digest May Earn a Portion of Sales from Products That Are Purchased Through Our Site As Part of Our Affiliate Partnerships with Retailers

The Grecian Valley at Stowe, Buckinghamshire (showing the Temple of Victory and Concorde), this year's beneficiary of the Royal Oak Foundation's gala dinner. Photo: Andrew Butler, courtesy of the National Trust THE REPORT The Royal Oak Foundation Looks to Stowe's 1730s Temple of Modern Virtue as its Latest Beneficiary The William Kent structure will benefit from the proceeds of the organization's annual Timeless Design Dinner By Mitchell Owens October 16, 2018 Stowe, the English country estate that shares its land with an elite boarding school, is a name that galvanizes attention in the architecture world. The sprawling Buckinghamshire destination, administered by the National Trust, astounds with the richness and variety of a property that was augmented, enriched, and, indeed, reshaped by an all-star 18th- century cast hired by the aristocratic Temple family: Charles Bridgeman, Sir John Vanbrugh, James Gibbs, William Kent, John Michael Rysbrack, and Lancelot “Capability” Brown, who was then just starting out on a career that would result in England’s transformation from stiff formal gardens to rolling landscapes that look utterly natural—but actually aren’t. “There’s so much going on at Stowe,” says David Nathans, the president of the Royal Oak Foundation, the energetic American fundraising arm of the National Trust. By that he means not only plants, trees, lakes, and the earthly like but scores of monuments, follies, temples, bridges, and other architectural delights that the public can see 365 days a year. Among them is what’s left of the 1730s Temple of Modern Virtue, a William Kent limestone frivolity that was built as a fool-the-eye ruin—it was intended as sarcastic commentary on Sir Robert Walpole, the avaricious British prime minister, who is depicted as a headless torso—but which has become, literally, tumble-down. -

The Gibbs Range of Classical Porches • the Gibbs Range of Classical Porches •

THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Andrew Smith – Senior Buyer C G Fry & Son Ltd. HADDONSTONE is a well-known reputable company and C G Fry & Son, award- winning house builder, has used their cast stone architectural detailing at a number of our South West developments over the last ten years. We erected the GIBBS Classical Porch at Tregunnel Hill in Newquay and use HADDONSTONE because of the consistency, product, price and service. Calder Loth, Senior Architectural Historian, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, USA As an advocate of architectural literacy, it is gratifying to have Haddonstone’s informative brochure defining the basic components of literate classical porches. Hugh Petter’s cogent illustrations and analysis of the porches’ proportional systems make a complex subject easily grasped. A porch celebrates an entrance; it should be well mannered. James Gibbs’s versions of the classical orders are the appropriate choice. They are subtlety beautiful, quintessentially English, and fitting for America. Jeremy Musson, English author, editor and presenter Haddonstone’s new Gibbs range is the result of an imaginative collaboration with architect Hugh Petter and draws on the elegant models provided by James Gibbs, one of the most enterprising design heroes of the Georgian age. The result is a series of Doric and Ionic porches with a subtle variety of treatments which can be carefully adapted to bring elegance and dignity to houses old and new. www.haddonstone.com www.adamarchitecture.com 2 • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Introduction The GIBBS Range of Classical Porches is designed The GIBBS Range is conceived around the two by Hugh Petter, Director of ADAM Architecture oldest and most widely used Orders - the Doric and and inspired by the Georgian architect James Ionic. -

Introduction-Translation-As-Art-History.Pdf

SUGATA RAY INTRODUCTION Translation as Art History In September 2016, more than two thousand scholars from forty- three countries gathered at the Comité International d’Histoire de l’Art’s Thirty- fourth World Congress of Art History in Beijing to collectively consider the terms that shape art history’s disciplinary contours in dispersed parts of the globe.1 The concern could not have been more pressing. As the call to decolonize the museum and the university gains momentum, the need to revisit the lan- guage of art history—terminologies, schemas, vocabularies, and so on— also accrues urgency, for lexica and terminologies frame the boundaries of what can and what cannot be called art history. Terms, as Raymond Williams reminds us, institutionalize knowledge through the manipulation of signification within language.2 Indeed, by now, we are all too cognizant of the threads that link the disciplinary structures of modern art history with both the project of the European Enlightenment and the epistemic violence of colonialism. The eighteenth- and nineteenth- century roots of the discipline, scholars have noted, lay in the “colonization of the world’s cultures” through a “totalizing notion of art.”3 More recently, in the wake of the Occupy movement, activists and community groups also have engaged with the colonial legacy of art history’s disciplinary paradigms. Consider, for instance, the demand to set up a Decolonization Commission at the Brooklyn Museum. That this call to decolonize the museum evokes a scene from the 2018 film Black Panther -

Thomas Hardwick Jnr. (1752-1827)

THOMAS HARDWICK JNR. (1752-1827) The name of Hardwick in the field of architecture was the most prominent name during the 19th century. From the late 18th century until 1892 the Hardwick Dynasty contributed some of the finest buildings in London and helped restore a great many too. Born in Brentford, greater London, to a prosperous master mason Thomas Hardwick Snr. (1725 -1798) who worked with the Adam brothers during the building of Syon House. Hardwick Jnr. underwent his training during the construction of the Somerset House and was tutored by William Chambers. He became a member of the Royal Academy and won the prestigious gold medal in architecture. Then came his travel to Europe with his close friend/rival Sir John Soane; together they visited Italy and France. Thomas became a notable church architect and the church of St Mary’s is his finest piece of work in London. The building is a prime example of Regency architecture. His other work included the restoration of St James, Piccadilly, St. Paul’s, Convent Garden and St Bartholomew-the-less, in Smithfield. He was also appointed Clerk of Works by King George III at both Hampton Court and Kew Palace. In his later years he became a tutor to none other than JMW Tuner whom he persuaded to concentrate more on painting rather than architecture! He had two sons, John Hardwick, whom became a famous magistrate in London, and also Philip (1792-1870) who would become the second architect in the Hardwick line and who took over his father’s office in 1825. -

Births, Marriages, and Deaths

thérite" was then opened by Mr. HAINWORTH, who stated that namely, with 1318. Hence, the deaths of last week were less- he had seen no cases of the genuine disease, although he had by about 100 than the number which would have occurred if a seen sore-throats of all kinds in abundance. He was anxious mortality equal to the average rate had prevailed. At the to obtain information as to the physical characters of the dis- present time the population appears to enjoy a fair amount of ease, as to its course, and as to its contagiousness. health, if this is measured by the experience of London itself Mr. PART gave the result of his experience. His first two in former seasons; sanitary defects become apparent on com- Jases -were fatal. Lately he had seen four or five others which paring its mortality -with that of places in more favourable had recovered. His cases had generally been ushered in by conditions. Whilst the deaths were low, the births were high, vomiting, although the worst case was not attended by that and the result is an excess in the latter, as compared with the symptom. Lately he had given carbonate of ammonia, with former, equal to 726. The mortality from small-pox again nutritious diet; and had used as an application nitric acid at shows an increase, the deaths in the last four weeks having drst. followed by gargles of chloride of soda. been successively 29, 13, 11, and 22. The disease seems to Mr. ADAMS thought that many cases of sore-throat, not true prevail in parts of the St. -

A Catalogue of the Fellows, Candidates, Licentiates [And Extra

MDCCCXXXVI. / Od- CATALOGUE OF THE FELLOWS, CANDIDATES, AND LICENTIATES, OF THE ftogal College of LONDON. STREET. PRINTED 1!Y G. WGOUFAM., ANGEL COURT, SKINNER A CATALOGUE OF THE FELLOWS, CANDIDATES, AND LICENTIATES, OF THE Ittojjal College of ^ijpstrtans, LONDON. FELLOWS. Sir Henry Halford, Bart., M.D., G.C.IL, President, Physician to their Majesties , Curzon-street . Devereux Mytton, M.D., Garth . John Latham, M.D., Bradwall-hall, Cheshire. Edward Roberts, M.D. George Paulet Morris, M.D., Prince s-court, St. James s-park. William Heberden, M.D., Elect, Pall Mall. Algernon Frampton, M.D., Elect, New Broad- street. Devey Fearon, M.D. Samuel Holland, M.D. James Franck, M.D., Bertford-street. Park- lane. Sir George Smith Gibbes, Knt., M.D. William Lambe, M.D., Elect, Kings-road, Bedford-row. John Johnstone, M.D., Birmingham. Sir James Fellowes, Knt., M.D., Brighton. Charles Price, M.D., Brighton. a 2 . 4 Thomas Turner, M.D., Elect, and Trea- Extraordinary to surer, Physician the Queen , Curzon-street Edward Nathaniel Bancroft, M.D., Jamaica. Charles Dalston Nevinson, M.D., Montagu- square. Robert Bree, M.D., Elect, Park-square , Regent’s-park. John Cooke, M.D., Gower-street Sir Arthur Brooke Faulkner, Knt., M.D., Cheltenham. Thomas Hume, M.D., Elect, South-street , Grosvenor-square. Peter Rainier, M.D., Albany. Tristram Whitter, M.D. Clement Hue, M.D., Elect, Guildford- street. John Bright, M.D., Manchester-square. James Cholmeley, M.D., Bridge-street Henry , Blackfriars. Sir Thomas Charles Morgan, Knt., M.D., Dublin. Richard Simmons, M.D. Joseph Ager, M.D., Great Portland-st. -

Biographical Appendix

Biographical Appendix The following women are mentioned in the text and notes. Abney- Hastings, Flora. 1854–1887. Daughter of 1st Baron Donington and Edith Rawdon- Hastings, Countess of Loudon. Married Henry FitzAlan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, 1877. Acheson, Theodosia. 1882–1977. Daughter of 4th Earl of Gosford and Louisa Montagu (daughter of 7th Duke of Manchester and Luise von Alten). Married Hon. Alexander Cadogan, son of 5th Earl of Cadogan, 1912. Her scrapbook of country house visits is in the British Library, Add. 75295. Alten, Luise von. 1832–1911. Daughter of Karl von Alten. Married William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester, 1852. Secondly, married Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, 1892. Grandmother of Alexandra, Mary, and Theodosia Acheson. Annesley, Katherine. c. 1700–1736. Daughter of 3rd Earl of Anglesey and Catherine Darnley (illegitimate daughter of James II and Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester). Married William Phipps, 1718. Apsley, Isabella. Daughter of Sir Allen Apsley. Married Sir William Wentworth in the late seventeenth century. Arbuthnot, Caroline. b. c. 1802. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. She did not marry. Arbuthnot, Marcia. 1804–1878. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. Married William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley, 1825. Aston, Barbara. 1744–1786. Daughter and co- heir of 5th Lord Faston of Forfar. Married Hon. Henry Clifford, son of 3rd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, 1762. Bannister, Henrietta. d. 1796. Daughter of John Bannister. She married Rev. Hon. Brownlow North, son of 1st Earl of Guilford, 1771. Bassett, Anne. Daughter of Sir John Bassett and Honor Grenville. -

Document.Pdf

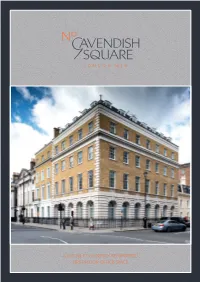

6,825 SQ FT OF NEWLY REFURBISHED FIRST FLOOR OFFICE SPACE Introducing 6,825 sq ft of newly refurbished, bright open plan office accommodation overlooking leafy Cavendish Square. CONVENIENTLY LOCATED WITH QUICK ACCESS ACROSS CENTRAL LONDON Oxford Circus Commissionaire Shower Newly Raised access 2 mins walk facilities and refurbished flooring WC spacious WCs to Cat A Bond Street* FLOOR PLAN 7 mins walk WC 6,825 sq ft Goodge Street 11 mins walk 643.06 sq m Suspended 3.4m floor to Excellent Fitted ceiling ceiling height natural light kitchenette *Elizabeth Line opens 2018 19 LOCAL AMENITIES NEW CAVENDISH STREET 15 1. The Wigmore 2. The Langham HARLEY STREET GLOUCESTER PLACE The Wallace 18 BBC 3. The Riding House Café Collection Broadcasting PORTLAND PLACE 6 House MARYLEBONE HIGH STREET 4. Pollen St Social BAKER STREET QUEEN ANNE STREET MANCHESTER SQUARE 5. Beast 19 2 3 10 PORTMAN SQUARE 8 MARYLEBONE LANE 1 6. The Ivy Café 16 7 17 7. Les 110 de Taillevent WIGMORE STREET CAVENDISH PLACE STREET CHANDOS 8. Cocoro Marble CAVENDISH Arch SQUARE 9. Swingers 14 19 11 HENRIETTA PLACE MARGARET STREET 10. Kaffeine DUKE STREET 9 11. Selfridges OXFORD STREET Bond Street 13 12. Carnaby St OXFORD STREET 5 13. John Lewis Oxford 14. St Christopher’s Place Circus PARK STREET REGENT STREET 15. Daylesford Bonhams NEW BOND STREET HANOVER SQUARE 16. Sourced Market GROSVENOR SQUARE BROOK STREET HANOVER STREET DAVIES STREET DAVIES 4 Liberty 17. Psycle GROSVENOR SQUARE 12 18. Third Space Marylebone MADDOX STREET 19. Q Park TERMS FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Sublease available until Matt Waugh Ed Arrowsmith December 2022 0207 152 5515 020 7152 5964 07912 977 980 07736 869 320 Rent on application [email protected] [email protected] Cushman & wakefield copyright 2018. -

Accounts of Debates in the House of Commons, March–April 1731, Supplementary to the Diary of the First Earl of Egmont

Accounts of Debates in the House of Commons, March–April 1731, Supplementary to the Diary of the First Earl of Egmont D. W. Hayton Introduction John Perceval (1683–1748), fourth baronet, of Burton Hall, near Kanturk in County Cork, created first Baron Perceval (in 1715), first Viscount Perceval (1723) and first Earl of Egmont (1733) in the Irish peerage, sat in the British House of Commons for the government borough of Harwich in the parliament of 1727–34, and left to posterity a diary containing accounts of debates in the Commons which constitute the best source for parliamentary proceedings during the period of Sir Robert Walpole’s prime ministership.1 This was published by the Historical Manuscripts Commission in three volumes between 1905 and 1909, as appendices to its sixteenth report.2 Elsewhere in Perceval’s large personal archive in the British Library other examples survive of the diarist’s craft and some of these have been published: in 1962 Robert McPherson edited the ‘journal’ compiled by Perceval from notes, minutes and papers while he was a trustee of the Georgia Society in the 1730s;3 in 1969 Aubrey Newman printed fragments from 1749–51 and 1760, illustrating the politics of the ‘Leicester House’ faction, with which Perceval was involved;4 in 1982 the present author published excerpts relating to Irish parliamentary proceedings in 1711 and 1713 from a ‘journal of public affairs’ kept by Perceval between 1711 and 1718;5 and in 1989 Mark Wenger edited Perceval’s diary of his travels in 1701 as a young man through the eastern and northern counties of England.6 Occasional references in the Historical Manuscripts Commission volumes indicate that Perceval had compiled other accounts of events – specifically of parliamentary debates – and forwarded them in correspondence. -

Marylebone Lane Area

DRAFT CHAPTER 5 Marylebone Lane Area At the time of its development in the second half of the eighteenth century the area south of the High Street was mostly divided between three relatively small landholdings separating the Portman and Portland estates. Largest was Conduit Field, twenty acres immediately east of the Portman estate and extending east and south to the Tyburn or Ay Brook and Oxford Street. This belonged to Sir Thomas Edward(e)s and later his son-in-law John Thomas Hope. North of that, along the west side of Marylebone Lane, were the four acres of Little Conduit Close, belonging to Jacob Hinde. Smaller still was the Lord Mayor’s Banqueting House Ground, a detached piece of the City of London Corporation’s Conduit Mead estate, bounded by the Tyburn, Oxford Street and Marylebone Lane. The Portland estate took in all the ground on the east side of Marylebone Lane, including the two island sites: one at the south end, where the parish court-house and watch-house stood, the other backing on to what is now Jason Court (John’s Court until 1895). This chapter is mainly concerned with Marylebone Lane, the streets on its east side north of Wigmore Street, and the southern extension of the High Street through the Hinde and part of the Hope–Edwardes estates, in the form of Thayer Street and Mandeville Place – excluding James Street, which is to be described together with the Hope–Edwardes estate generally in a later volume. The other streets east of Marylebone Lane – Henrietta Place and Wigmore Street – are described in Chapters 8 and 9.